From the Trenches

Passage to the Afterlife

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, December 10, 2018

A monument that may lead to a shift in scholars’ vision of Ireland’s prehistoric past has been discovered in the Boyne Valley north of Dublin. The 5,500-year-old passage tomb—a complex of multiple burials—is thought to be one of the oldest ever discovered in the area, which is renowned for its concentration of Neolithic sites. One of the stones that once covered the tomb is especially well carved. The tomb’s relatively small size suggests that it was constructed earlier than other tombs in the valley, says archaeologist Stephen Davis of University College Dublin. It may date closer to when people first began farming in the region, around 3800 B.C. “The tomb seems to mark a transition towards a time when religion played a greater role in people’s lives,” he says. To some extent, suggests Davis, the free time to build such monuments must have been the result of an agricultural surplus.

A monument that may lead to a shift in scholars’ vision of Ireland’s prehistoric past has been discovered in the Boyne Valley north of Dublin. The 5,500-year-old passage tomb—a complex of multiple burials—is thought to be one of the oldest ever discovered in the area, which is renowned for its concentration of Neolithic sites. One of the stones that once covered the tomb is especially well carved. The tomb’s relatively small size suggests that it was constructed earlier than other tombs in the valley, says archaeologist Stephen Davis of University College Dublin. It may date closer to when people first began farming in the region, around 3800 B.C. “The tomb seems to mark a transition towards a time when religion played a greater role in people’s lives,” he says. To some extent, suggests Davis, the free time to build such monuments must have been the result of an agricultural surplus.

No Rainbow Required

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, December 10, 2018

On the site of Como’s former Cressoni Theater, once one of northern Italy’s great opera houses, excavators have found a soapstone vessel filled with hundreds of Late Antique gold coins. The location, now slated for luxury apartments, is close to the forum of Novum Comum, a settlement founded by Julius Caesar in 59 B.C. Thus far, conservators have removed several dozen coins from the vessel and identified five emperors’ portraits, all dating to the fourth and fifth centuries A.D., depicted on the coins.

On the site of Como’s former Cressoni Theater, once one of northern Italy’s great opera houses, excavators have found a soapstone vessel filled with hundreds of Late Antique gold coins. The location, now slated for luxury apartments, is close to the forum of Novum Comum, a settlement founded by Julius Caesar in 59 B.C. Thus far, conservators have removed several dozen coins from the vessel and identified five emperors’ portraits, all dating to the fourth and fifth centuries A.D., depicted on the coins.

Bath Tiles

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, December 10, 2018

Brightly colored tiles have been uncovered during excavations in advance of restoration of England’s Bath Abbey. The site has been home to religious buildings for more than 1,000 years. The current church, which was completed in the seventeenth century, was constructed above the remains of a Norman-era cathedral that had fallen into disrepair by the late 1400s. The tiles once formed a portion of that cathedral’s floor. “In situ medieval tile floors like this are incredibly rare,” explains project director Cai Mason of Wessex Archaeology. “The only reason this one survived is that the Norman cathedral was knocked down and essentially buried during construction of the current building, saving the original flooring.” The tiles have now been covered by a protective layer before new floors are installed.

Brightly colored tiles have been uncovered during excavations in advance of restoration of England’s Bath Abbey. The site has been home to religious buildings for more than 1,000 years. The current church, which was completed in the seventeenth century, was constructed above the remains of a Norman-era cathedral that had fallen into disrepair by the late 1400s. The tiles once formed a portion of that cathedral’s floor. “In situ medieval tile floors like this are incredibly rare,” explains project director Cai Mason of Wessex Archaeology. “The only reason this one survived is that the Norman cathedral was knocked down and essentially buried during construction of the current building, saving the original flooring.” The tiles have now been covered by a protective layer before new floors are installed.

India's Anonymous Artists

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, December 10, 2018

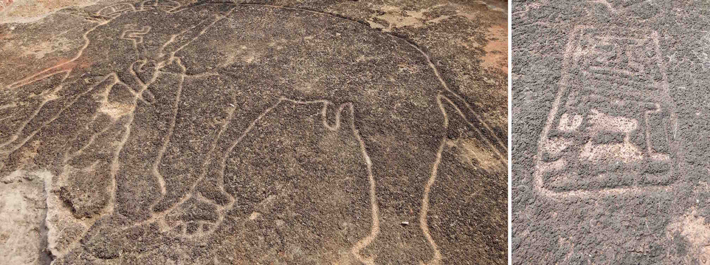

In the coastal Konkan region of India’s western state of Maharashtra, around 1,000 petroglyphs have been discovered spread out over dozens of different sites. Nearly all of them are found on hilltops. In a few cases, local people were aware of the designs, but most were previously unknown—and many were hidden beneath a layer of earth. The carvings depict a wide range of subjects, including elephants, monkeys, peacocks, sharks, and alligators, as well as human figures and geometric patterns. According to Tejas Garge, director of the Maharashtra state archaeology department, the drawings were probably created between 12,000 and 5,000 years ago. Little is known of their creators, however, as no associated settlement sites have been found. Given that the carvings don’t depict domesticated animals and agricultural activities, says Garge, the people who made them were likely hunter-gatherers.

In the coastal Konkan region of India’s western state of Maharashtra, around 1,000 petroglyphs have been discovered spread out over dozens of different sites. Nearly all of them are found on hilltops. In a few cases, local people were aware of the designs, but most were previously unknown—and many were hidden beneath a layer of earth. The carvings depict a wide range of subjects, including elephants, monkeys, peacocks, sharks, and alligators, as well as human figures and geometric patterns. According to Tejas Garge, director of the Maharashtra state archaeology department, the drawings were probably created between 12,000 and 5,000 years ago. Little is known of their creators, however, as no associated settlement sites have been found. Given that the carvings don’t depict domesticated animals and agricultural activities, says Garge, the people who made them were likely hunter-gatherers.

Land of the Ice and Snow

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, December 10, 2018

The Vikings are renowned for having traveled great distances from their homeland in Scandinavia. A new study suggests that many residents of Sigtuna, a major Viking town in eastern Sweden, were themselves immigrants from afar. Researchers from Stockholm University sequenced the genomes and analyzed strontium isotopes from the remains of 16 people buried in Sigtuna between the tenth and twelfth centuries. Isotope analysis showed that eight of the 16 individuals had grown up in or near the town, and eight had grown up elsewhere. Of those who moved to the town, four had genetic features suggesting they had come from other parts of Scandinavia, while four appeared to have arrived from farther away, most likely Eastern Europe. Two of those who had grown up locally had unusual genetic profiles for the area, suggesting that they were second-generation immigrants. “We knew that Sigtuna had a lot of contact with other regions,” says researcher Maja Krzewinska, “but we didn’t know to what degree and we didn’t know whether the foreigners actually lived and stayed in Sigtuna. Now we can prove it.”

The Vikings are renowned for having traveled great distances from their homeland in Scandinavia. A new study suggests that many residents of Sigtuna, a major Viking town in eastern Sweden, were themselves immigrants from afar. Researchers from Stockholm University sequenced the genomes and analyzed strontium isotopes from the remains of 16 people buried in Sigtuna between the tenth and twelfth centuries. Isotope analysis showed that eight of the 16 individuals had grown up in or near the town, and eight had grown up elsewhere. Of those who moved to the town, four had genetic features suggesting they had come from other parts of Scandinavia, while four appeared to have arrived from farther away, most likely Eastern Europe. Two of those who had grown up locally had unusual genetic profiles for the area, suggesting that they were second-generation immigrants. “We knew that Sigtuna had a lot of contact with other regions,” says researcher Maja Krzewinska, “but we didn’t know to what degree and we didn’t know whether the foreigners actually lived and stayed in Sigtuna. Now we can prove it.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

The Case of the Stolen Sumerian Antiquities

Off the Grid

Ancient Amazonian Chocolatiers

Fit for a Prince

When Things Got Cheesy

Funny Business

Double Vision

Raise a Toast to the Aurochs

A Lost Sock's Secrets

Land of the Ice and Snow

Bath Tiles

India's Anonymous Artists

No Rainbow Required

Passage to the Afterlife

World Roundup

Scottish clan memorabilia, a conquistador shrine, Neolithic nutmeg, Maya sea salt harvesters, and a Chinese model house

Artifact

Heirloom apparent

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement