Features

Inside King Tut’s Tomb

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Tuesday, July 26, 2022

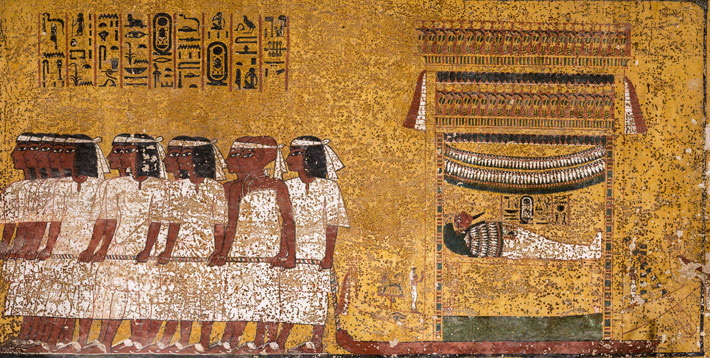

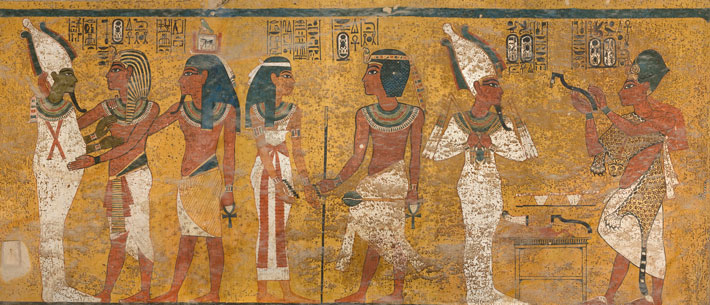

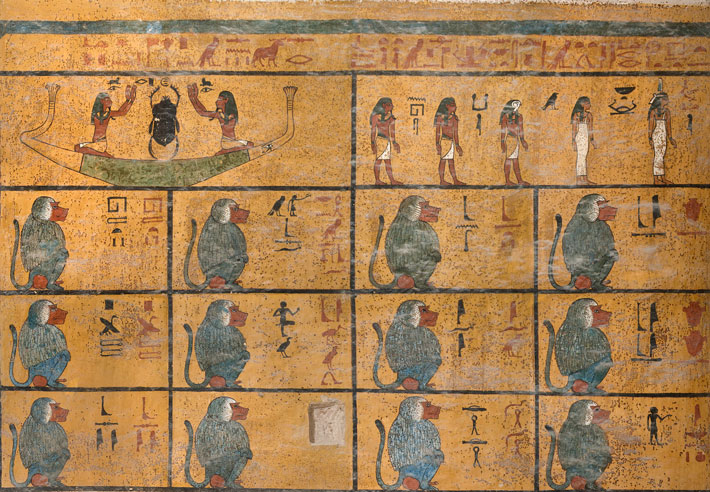

In ancient Egypt, the passage to the afterlife was an arduous one. Even at the end of the journey, the deceased could be turned away from the paradise of the Field of Reeds if their heart tipped the scales when weighed against a feather. Often elements of the transit were painted on tomb walls, a process that, judging from the accomplished and detailed murals that have survived, would have consumed a great deal of time. Although the walls of the pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb are decorated with familiar scenes of this path to paradise, new research is now telling a fresh story about the real-world turmoil caused by the sudden death of the young king.

In ancient Egypt, the passage to the afterlife was an arduous one. Even at the end of the journey, the deceased could be turned away from the paradise of the Field of Reeds if their heart tipped the scales when weighed against a feather. Often elements of the transit were painted on tomb walls, a process that, judging from the accomplished and detailed murals that have survived, would have consumed a great deal of time. Although the walls of the pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb are decorated with familiar scenes of this path to paradise, new research is now telling a fresh story about the real-world turmoil caused by the sudden death of the young king.

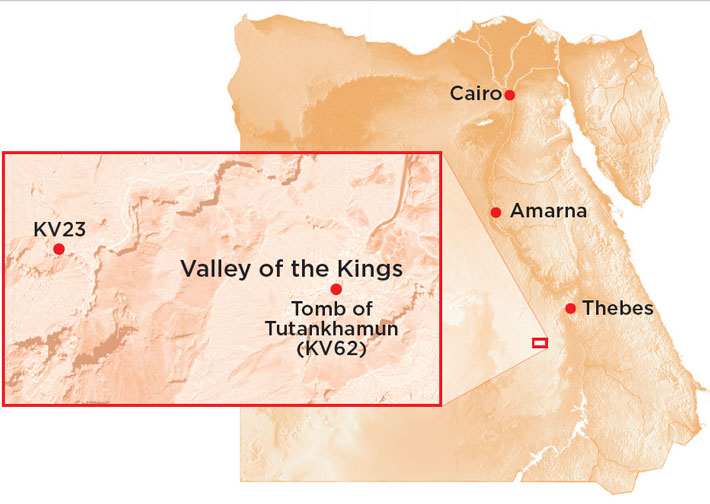

The pharaoh, who was first known as Tutankhaten (r. ca. 1336–1327 B.C.), was crowned at the tender age of eight or nine, but his reign was not to last long, and he died before he turned 20. Scholars debate the cause, or causes, of Tut’s death, but all agree that it came suddenly. Tut’s unexpected passing presented a challenge—his planned tomb in the Valley of the Kings hadn’t yet been completed. Work on that tomb (KV23) was abandoned, and one in the eastern section of the valley originally intended for someone else (KV62) was hastily made ready. Egyptologist Kent Weeks, who directs excavations in the valley, says that KV62 was probably originally meant for either Tut’s predecessor, Smenkhkare (r. ca. 1336 B.C.), or his successor, Ay (r. ca. 1327–1323 B.C.).

The pharaoh, who was first known as Tutankhaten (r. ca. 1336–1327 B.C.), was crowned at the tender age of eight or nine, but his reign was not to last long, and he died before he turned 20. Scholars debate the cause, or causes, of Tut’s death, but all agree that it came suddenly. Tut’s unexpected passing presented a challenge—his planned tomb in the Valley of the Kings hadn’t yet been completed. Work on that tomb (KV23) was abandoned, and one in the eastern section of the valley originally intended for someone else (KV62) was hastily made ready. Egyptologist Kent Weeks, who directs excavations in the valley, says that KV62 was probably originally meant for either Tut’s predecessor, Smenkhkare (r. ca. 1336 B.C.), or his successor, Ay (r. ca. 1327–1323 B.C.).

By the standard of other royal tombs, Tut’s is quite small, composed of four small rooms, only one of which is painted. Despite its size, however, the tomb was filled with everything the pharaoh would need for the afterlife, including furniture, chariots, wine, fresh food, clothing, shaving and writing equipment, musical instruments, games, and weapons. There were four gold shrines, one fitted inside the other, within which were nested quartzite, wooden, and golden sarcophagi. The innermost sarcophagus contained the pharaoh’s mummy wearing a 24-pound solid gold mask. There is evidence that Tut’s tomb was robbed twice in antiquity—once, says Weeks, only a short time after the entrance was sealed.

When British archaeologist Howard Carter excavated the tomb in 1922, however, most of the extraordinary grave goods were in place, and the tomb appeared relatively intact. With the exception of the sarcophagus containing the mummy, all the artifacts have been removed to the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. What remains are four painted walls depicting scenes of the pharaoh’s transition to the afterlife, which, for Carter, were of far less importance than the golden artifacts.

In 2009, after nearly 100 years and millions of visitors, the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities’ concern for the state of Tut’s tomb was mounting. They called upon the Getty Conservation Institute (GCI) to study the tomb, in particular the wall paintings, and to develop plans to safeguard it. “When we got there, we were surprised because the paintings’ condition was actually very good,” says GCI’s Lori Wong. “The fact that the paintings are complete puts everything in perspective. We worked here for 10 years, whereas the lifespan of these paintings is 3,300 years.”

Bringing Back Moche Badminton

Thursday, May 30, 2019

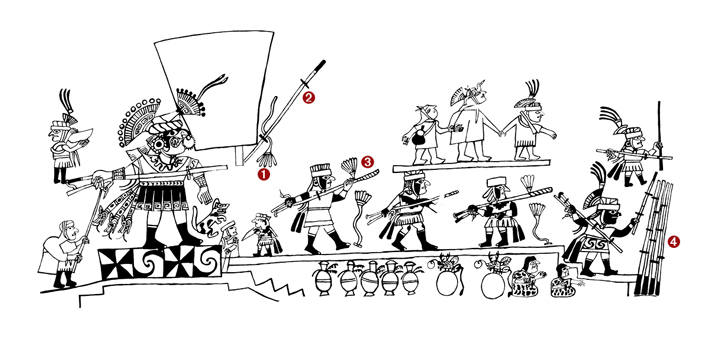

When Christopher Donnan began studying the art created by Peru’s Moche culture more than 50 years ago, he wasn’t sure how much it reflected ancient reality. From about A.D. 200 to 850, the Moche lived in the arid valleys of Peru’s northern coast, where they practiced intensive irrigation agriculture and built vast ceremonial complexes. Moche artists created murals and decorated pottery with vivid images of fantastic rituals featuring participants who were part animal and part human. They also painted scenes of figures, some wearing elaborate clothing that indicated their elite status, engaged in a mysterious spear-throwing activity scholars dubbed “ceremonial badminton” due to the use of a feathered object that looks somewhat like a shuttlecock.

Early in his career, Donnan wondered whether the images might depict mythical figures operating on a supernatural plane rather than real people enacting ceremonies on Earth. The rituals certainly seemed to stretch the limits of reality. Chief among them was the sacrifice ceremony, in which attendants slit prisoners’ throats and collected their blood in goblets, which were then presented to the presiding priest. The beings participating in the sacrifice ceremony took human form, but had body parts such as fangs, jaguar heads, and bird beaks. There were also depictions of ceremonial badminton contests that showed groups of figures armed with a type of spear-thrower called an atlatl, which is essentially a stick with a handle on one end and a hook or socket that attaches to a spear on the other. Participants seemed to use their atlatls to hurl spears with feathered objects attached to them. Like the sacrifice ceremony, ceremonial badminton could have been an actual event or a supernatural contest that occurred largely in the Moche mythological realm. “When I looked at these rituals I often wondered if the activities were real. Did they really do that?” says Donnan.

Early in his career, Donnan wondered whether the images might depict mythical figures operating on a supernatural plane rather than real people enacting ceremonies on Earth. The rituals certainly seemed to stretch the limits of reality. Chief among them was the sacrifice ceremony, in which attendants slit prisoners’ throats and collected their blood in goblets, which were then presented to the presiding priest. The beings participating in the sacrifice ceremony took human form, but had body parts such as fangs, jaguar heads, and bird beaks. There were also depictions of ceremonial badminton contests that showed groups of figures armed with a type of spear-thrower called an atlatl, which is essentially a stick with a handle on one end and a hook or socket that attaches to a spear on the other. Participants seemed to use their atlatls to hurl spears with feathered objects attached to them. Like the sacrifice ceremony, ceremonial badminton could have been an actual event or a supernatural contest that occurred largely in the Moche mythological realm. “When I looked at these rituals I often wondered if the activities were real. Did they really do that?” says Donnan.

Now, building on decades of archaeological discoveries and his own extensive experience analyzing depictions of Moche rituals, Donnan, an archaeologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, has re-created ceremonial badminton. In bringing to life a contest that for more than 1,000 years was confined to painted scenes on ancient pottery, he has been able to get a glimpse into the lived experience of the Moche that artifacts rarely afford.

The question of whether or not Moche art depicts real events was settled in 1987, when Peruvian archaeologist Walter Alva excavated the tomb of a Moche nobleman now known as the Lord of Sipan. This nobleman had been buried in northern Peru’s Lambayeque Valley along with the bodies of six attendants. The lord wore an elaborate costume that closely resembled the artistic representations of the sacrifice ceremony’s participants. In a nearby tomb, archaeologists discovered the burial of a man who wore a large owl headdress that mimicked how a figure known as the Bird Priest appears in Moche art. Alva and his team even found goblets that had once held the victims’ blood. “That really changed everything,” recalls Donnan, who analyzed Alva’s discoveries and confirmed their parallels to the art he knew so well. “This made clear that what you see in Moche art is real.”

|

Video:

|

Playing Moche Toss

|

Mapping the Past

Thursday, April 11, 2019

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Mapping the Past

Bringing Back Moche Badminton

Inside King Tut’s Tomb

Letter from the Dead Sea

From the Trenches

Epic Proportions

Off the Grid

Stabbed in the Back

A Fox in the House

Tigress by the Tail

Family Secrets

Cold War Storage

Marrow of Humanity

Maya Beekeepers

Roman Soldier Scribbles

Understanding Hornet's Fate

Viking Warrioress

Colonial Cooling

Temple of the Flayed Lord

Celtic Curiosity

Submerged Scottish Forest

World Roundup

American whaler petroglyphs, Chinese “elixir of immortality,” Neanderthal footprints, and Ice Age rabbit hunting

Artifact

At some point in the past

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

What the team was very curious about was something that had worried Egyptologists for decades—the puzzling brown spots that speckle the paintings. “Our main concern was that whatever was making the spots was still alive, and that there was a continuing risk of them damaging the paintings,” Wong says. The team conducted advanced microbiological analyses and compared current images of the tomb with those taken by photographer Harry Burton during Carter’s excavation—reproduced at a scale of one to one with the actual paintings using the original glass plate negatives. They concluded that the spots hadn’t grown or changed at all in nearly a century. “Whatever originally made the spots, they’re now dead,” says Wong. “They are a byproduct of some metabolic process, perhaps occurring thousands of years ago, and they aren’t going to grow anymore.”

What the team was very curious about was something that had worried Egyptologists for decades—the puzzling brown spots that speckle the paintings. “Our main concern was that whatever was making the spots was still alive, and that there was a continuing risk of them damaging the paintings,” Wong says. The team conducted advanced microbiological analyses and compared current images of the tomb with those taken by photographer Harry Burton during Carter’s excavation—reproduced at a scale of one to one with the actual paintings using the original glass plate negatives. They concluded that the spots hadn’t grown or changed at all in nearly a century. “Whatever originally made the spots, they’re now dead,” says Wong. “They are a byproduct of some metabolic process, perhaps occurring thousands of years ago, and they aren’t going to grow anymore.”