From the Trenches

Understanding Hornet's Fate

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Thursday, April 11, 2019

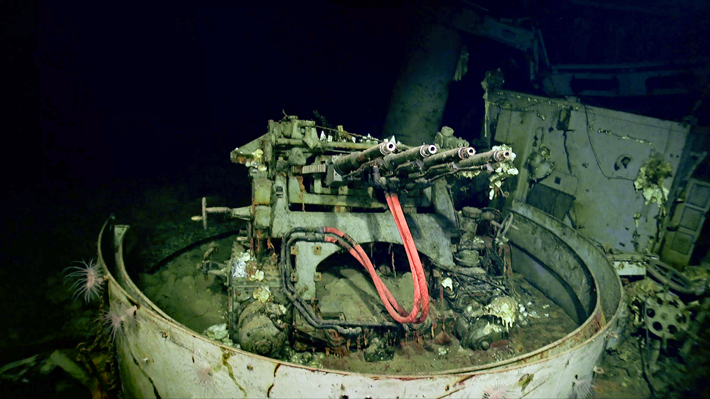

On the evening of October 26, 1942, the Yorktown-class aircraft carrier USS Hornet sank to the bottom of the South Pacific during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, ending a brief but storied career that included a pivotal role in the Battle of Midway. Now, with the aid of U.S. and Japanese naval records, the crew of Research Vessel Petrel has located the wreckage of Hornet near the Solomon Islands, almost 17,500 feet underwater. “There’s no current at that depth, so the level of preservation is in many ways pristine,” says underwater archaeologist Robert Neyland of the Naval History and Heritage Command, who accompanied Petrel’s crew on the expedition.

On the evening of October 26, 1942, the Yorktown-class aircraft carrier USS Hornet sank to the bottom of the South Pacific during the Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, ending a brief but storied career that included a pivotal role in the Battle of Midway. Now, with the aid of U.S. and Japanese naval records, the crew of Research Vessel Petrel has located the wreckage of Hornet near the Solomon Islands, almost 17,500 feet underwater. “There’s no current at that depth, so the level of preservation is in many ways pristine,” says underwater archaeologist Robert Neyland of the Naval History and Heritage Command, who accompanied Petrel’s crew on the expedition.

The first evidence of damage to Hornet that Petrel's crew documented—the result of Japanese bomb and torpedo attacks, as well as the U.S. Navy’s attempts to scuttle her—corroborates survivor accounts. Damage from the later violent torpedo attack that finally sank the carrier, however, was revealed to be more extensive than previously known. The team also found personal effects, including a coat still hanging from a door near the stern, that offer a glimpse of the lives of the 2,512 men aboard Hornet, 129 of whom perished in the battle.

The first evidence of damage to Hornet that Petrel's crew documented—the result of Japanese bomb and torpedo attacks, as well as the U.S. Navy’s attempts to scuttle her—corroborates survivor accounts. Damage from the later violent torpedo attack that finally sank the carrier, however, was revealed to be more extensive than previously known. The team also found personal effects, including a coat still hanging from a door near the stern, that offer a glimpse of the lives of the 2,512 men aboard Hornet, 129 of whom perished in the battle.

Roman Soldier Scribbles

By JASON URBANUS

Thursday, April 11, 2019

While gathering material from a stone quarry in Cumbria’s Gelt Woods for renovations to nearby Hadrian’s Wall, Roman soldiers carved personal inscriptions, funny cartoons, and “good luck” phallic symbols into the rock face. This 1,800-year-old graffiti is now being documented by archaeologists from Historic England and Newcastle University. One soldier seems to have etched a humorous caricature of his perhaps overly demanding boss, Agricola. “This was hard and potentially dangerous work that they were doing and this is a really human reaction to that environment,” says Historic England’s Mike Collins.

While gathering material from a stone quarry in Cumbria’s Gelt Woods for renovations to nearby Hadrian’s Wall, Roman soldiers carved personal inscriptions, funny cartoons, and “good luck” phallic symbols into the rock face. This 1,800-year-old graffiti is now being documented by archaeologists from Historic England and Newcastle University. One soldier seems to have etched a humorous caricature of his perhaps overly demanding boss, Agricola. “This was hard and potentially dangerous work that they were doing and this is a really human reaction to that environment,” says Historic England’s Mike Collins.

Equipped with laser-scanning technology, archaeologists were suspended 30 feet down the quarry face to document the graffiti, which was first discovered in the eighteenth century. In the process, they identified several previously unknown examples. Because the inscriptions record names, ranks, military units, and even a date corresponding to A.D. 207, they are direct evidence of the early third-century building project to refortify Hadrian’s Wall. Researchers will use the images to create a 3-D model of the rock face.

Equipped with laser-scanning technology, archaeologists were suspended 30 feet down the quarry face to document the graffiti, which was first discovered in the eighteenth century. In the process, they identified several previously unknown examples. Because the inscriptions record names, ranks, military units, and even a date corresponding to A.D. 207, they are direct evidence of the early third-century building project to refortify Hadrian’s Wall. Researchers will use the images to create a 3-D model of the rock face.

Marrow of Humanity

By JASON URBANUS

Thursday, April 11, 2019

Consuming the meat of large animals is generally thought to have been instrumental in human evolution. It allowed early hominins, such as australopithecines, to begin developing larger brains some 3.4 million years ago. At a time when early hominins were not yet able to manufacture and hunt with sophisticated tools, however, obtaining meat from animals that significantly outweighed them was a dangerous undertaking. Researchers now believe that our human ancestors may have first acquired the taste for meat by scavenging carcasses left behind by other predators. Even if most of the meat was rotten or had already been consumed, early hominins may have used stones and other tools to smash open bones and access fatty marrow deposits, an invaluable source of the nutrients required by their very large brains. “Targeting marrow not only enables a stone-wielding hominin to access a novel resource that can’t be accessed by most other carnivores, but it was a relatively low-risk food,” says Yale University paleoanthropologist Jessica Thompson. This combination of high caloric returns at a low cost may have served as the ideal gateway to a long-standing carnivorous habit.

Maya Beekeepers

By ERIC A. POWELL

Thursday, April 11, 2019

Evidence of the handiwork of early Maya beekeepers has been unearthed at the ancient city of Nakum in northeastern Guatemala. Beneath a vast ritual platform dating from around 100 B.C. to A.D. 300, a team led by Jagiellonian University archaeologist Jaroslaw Zralka discovered a foot-long, barrel-shaped ceramic tube with covers at each end. Initially, Zralka and his colleagues thought the artifact might be a drum buried as an offering. But they soon learned that the tube was nearly identical to wooden beehives still made from hollow logs by Maya in the northern Yucatan. Most pre-Columbian beehives were also likely made from wood, but none of these have been discovered. The Nakum tube is the only known surviving example of an ancient Maya beehive.

Evidence of the handiwork of early Maya beekeepers has been unearthed at the ancient city of Nakum in northeastern Guatemala. Beneath a vast ritual platform dating from around 100 B.C. to A.D. 300, a team led by Jagiellonian University archaeologist Jaroslaw Zralka discovered a foot-long, barrel-shaped ceramic tube with covers at each end. Initially, Zralka and his colleagues thought the artifact might be a drum buried as an offering. But they soon learned that the tube was nearly identical to wooden beehives still made from hollow logs by Maya in the northern Yucatan. Most pre-Columbian beehives were also likely made from wood, but none of these have been discovered. The Nakum tube is the only known surviving example of an ancient Maya beehive.

“Honey was probably among the most popular products exchanged and traded by the pre-Columbian Maya,” says Zralka. “So beekeeping was a very important activity in their daily life, as well as in religious activities.” Near the beehive, Zralka and his team found nine unbaked clay heads arranged in a circle, perhaps depicting gods important to the continued success of Nakum’s beekeepers.

Cold War Storage

By DANIEL WEISS

Thursday, April 11, 2019

In the late 1960s, the Soviets commissioned a trio of bases designed to store nuclear warheads in remote, forested areas of western Poland. The warheads, which ranged from 0.5 to 500 kilotons each, were intended to be fired at areas of West Germany and Denmark. Although the bases were secret, and attempts were made to camouflage them, the CIA had definitively identified their purpose by 1972.

In the late 1960s, the Soviets commissioned a trio of bases designed to store nuclear warheads in remote, forested areas of western Poland. The warheads, which ranged from 0.5 to 500 kilotons each, were intended to be fired at areas of West Germany and Denmark. Although the bases were secret, and attempts were made to camouflage them, the CIA had definitively identified their purpose by 1972.

Now, using declassified satellite imagery, airborne laser scanning, and on-the-ground exploration, Grzegorz Kiarszys of the University of Szczecin has carried out the first archaeological investigation of the bases. Little remains at the sites apart from the bunkers used to store the actual warheads. When they were operational, however, Kiarszys knows from archival photographs and the contents of trash pits, the bases included facilities to support not just the military personnel responsible for maintaining the warheads, but their families as well. “The Russian generals created an illusion of everyday, normal life at the bases,” says Kiarszys. “There were soccer fields, playgrounds, and kindergartens at every base.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Mapping the Past

Bringing Back Moche Badminton

Inside King Tut’s Tomb

Letter from the Dead Sea

From the Trenches

Epic Proportions

Off the Grid

Stabbed in the Back

A Fox in the House

Tigress by the Tail

Family Secrets

Cold War Storage

Marrow of Humanity

Maya Beekeepers

Roman Soldier Scribbles

Understanding Hornet's Fate

Viking Warrioress

Colonial Cooling

Temple of the Flayed Lord

Celtic Curiosity

Submerged Scottish Forest

World Roundup

American whaler petroglyphs, Chinese “elixir of immortality,” Neanderthal footprints, and Ice Age rabbit hunting

Artifact

At some point in the past

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement