Letter from the Dead Sea

Life in a Busy Oasis

By SARA TOTH STUB

Thursday, April 11, 2019

The Dead Sea includes the lowest point on Earth, at more than 1,400 feet below sea level, and lies in a long and narrow desert valley that runs through Israel, Jordan, and the West Bank. The sea itself is nearly 1,000 feet deep and covers more than 200 square miles, but its water is too salty to support any life beyond microscopic bacteria. Called a “sea” in multiple languages, including Hebrew and Arabic, this body of water is actually an inland lake, fed mainly by the Jordan River at its northern end. Green oases of palm trees and freshwater springs dot the land around the Dead Sea, but the terrain is overwhelmingly barren and rocky, with mountains rising along both the eastern and western shores.

Despite the harsh landscape, people have lived alongside the Dead Sea for millennia, drawn in part by the valuable minerals that can be harvested from its water and mud, as well as the maritime transport routes and trade links it provides. Located just 20 miles from Jerusalem, the Dead Sea has played an important political and economic role in the Near East since at least the seventh century B.C., when boats loaded with salt, bitumen, and crops likely first plied its waters, their cargo destined for Jerusalem, Jericho, and Mediterranean ports. “The Dead Sea gradually becomes this place where people see that they can make a lot of money,” says King’s College London archaeologist Joan Taylor. “The economic resources, from salt to asphalt to what was grown around it in the oases, are incredibly significant. It’s one of the most extraordinary places in the world.”

One place where archaeologists have unearthed abundant evidence of people’s long relationship with this unique body of water is Ein Gedi, the region’s largest oasis, which covers more than 250 acres on the lake’s western shore. Here, a team led by archaeologists Orit Peleg-Barkat of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Gideon Hadas of Ben Gurion University’s Dead Sea-Arava Science Center is uncovering the remains of a Jewish village that thrived for more than a thousand years. As a direct consequence of the rule of a long series of powers, including the Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, and Roman Empires, all of whom were heavily invested in the village’s economy, Ein Gedi’s inhabitants reaped the benefits of their unusual environment—a lush oasis with easy access to the Dead Sea’s mineral riches. “This may be the most beautiful place in the world,” says Hadas, “but it all has to do with the environment and resources. That’s what brings people here.”

One place where archaeologists have unearthed abundant evidence of people’s long relationship with this unique body of water is Ein Gedi, the region’s largest oasis, which covers more than 250 acres on the lake’s western shore. Here, a team led by archaeologists Orit Peleg-Barkat of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Gideon Hadas of Ben Gurion University’s Dead Sea-Arava Science Center is uncovering the remains of a Jewish village that thrived for more than a thousand years. As a direct consequence of the rule of a long series of powers, including the Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, and Roman Empires, all of whom were heavily invested in the village’s economy, Ein Gedi’s inhabitants reaped the benefits of their unusual environment—a lush oasis with easy access to the Dead Sea’s mineral riches. “This may be the most beautiful place in the world,” says Hadas, “but it all has to do with the environment and resources. That’s what brings people here.”

The 2019 excavation season, which concluded a 16-year-long investigation of dwellings and other structures from the Second Temple and Byzantine periods, built on earlier excavations going back to the 1960s. Those previous digs had exposed remains that date back more than 6,000 years, including an ancient temple, dozens of houses, Jewish ritual baths, a Byzantine synagogue, and agricultural terraces, but also left many questions. During the most recent excavations, the team sought to understand more about the village’s economy and trade connections, as well as how it weathered the chaotic last years of the ancient province of Judea and its eventual incorporation into the Roman Empire. Hadas and his colleagues are showing that evidence of the lives of Ein Gedi’s ancient villagers are key to understanding how the Dead Sea enriched, supported, and connected those able to prosper on its inhospitable shores.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Mapping the Past

Bringing Back Moche Badminton

Inside King Tut’s Tomb

Letter from the Dead Sea

From the Trenches

Epic Proportions

Off the Grid

Stabbed in the Back

A Fox in the House

Tigress by the Tail

Family Secrets

Cold War Storage

Marrow of Humanity

Maya Beekeepers

Roman Soldier Scribbles

Understanding Hornet's Fate

Viking Warrioress

Colonial Cooling

Temple of the Flayed Lord

Celtic Curiosity

Submerged Scottish Forest

World Roundup

American whaler petroglyphs, Chinese “elixir of immortality,” Neanderthal footprints, and Ice Age rabbit hunting

Artifact

At some point in the past

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Today, the ancient village of Ein Gedi lies on the property of an Israeli kibbutz, or communal agricultural settlement, that produces dates and bottles mineral water collected from four large natural springs. These springs first attracted people more than six millennia ago, when a Copper Age farming people known as the Ghassulians, who inhabited the southern Levant between 4400 and 3500 B.C., built a temple here. Perched high on a natural terrace above one of Ein Gedi’s springs, the temple commands a sweeping view of the Dead Sea. In the 4,000-square-foot religious compound, consisting of four stone and mudbrick buildings, archaeologists have found a circular stone structure with a basin connected to a drainage channel. This, along with the discovery of several rocks just outside the complex with holes bored in them, may be evidence of Ghassulian rituals centered on water. After the Ghassulians left in the fourth millennium B.C., their entire culture seems to have disappeared from the region for reasons that remain unknown. The oasis, along with most of the area around the Dead Sea, remained empty of permanent settlers for the next 3,000 years. “We don’t know exactly why no one lived around here in that period,” says Hadas. “We have no remains to tell us anything other than that it was empty.”

Today, the ancient village of Ein Gedi lies on the property of an Israeli kibbutz, or communal agricultural settlement, that produces dates and bottles mineral water collected from four large natural springs. These springs first attracted people more than six millennia ago, when a Copper Age farming people known as the Ghassulians, who inhabited the southern Levant between 4400 and 3500 B.C., built a temple here. Perched high on a natural terrace above one of Ein Gedi’s springs, the temple commands a sweeping view of the Dead Sea. In the 4,000-square-foot religious compound, consisting of four stone and mudbrick buildings, archaeologists have found a circular stone structure with a basin connected to a drainage channel. This, along with the discovery of several rocks just outside the complex with holes bored in them, may be evidence of Ghassulian rituals centered on water. After the Ghassulians left in the fourth millennium B.C., their entire culture seems to have disappeared from the region for reasons that remain unknown. The oasis, along with most of the area around the Dead Sea, remained empty of permanent settlers for the next 3,000 years. “We don’t know exactly why no one lived around here in that period,” says Hadas. “We have no remains to tell us anything other than that it was empty.” The village was one of several new settlements built east of Jerusalem, then the capital of the Jewish kingdom of Judea and a loyal vassal state of the Assyrian Empire. Settling at Ein Gedi was part of a trend of Judean expansion driven by the need to cultivate more land and ensure the Assyrian rulers access to the Dead Sea and its minerals. The words “for the king” stamped onto many vessels found at the site make it clear that the central government in Jerusalem controlled the economy, which relied on producing dates, grain, and salt.

The village was one of several new settlements built east of Jerusalem, then the capital of the Jewish kingdom of Judea and a loyal vassal state of the Assyrian Empire. Settling at Ein Gedi was part of a trend of Judean expansion driven by the need to cultivate more land and ensure the Assyrian rulers access to the Dead Sea and its minerals. The words “for the king” stamped onto many vessels found at the site make it clear that the central government in Jerusalem controlled the economy, which relied on producing dates, grain, and salt. Boats are largely absent on the Dead Sea today, aside from a few tourist and scientific vessels, in part because the area is a military zone and forms part of the international border between Israel and Jordan. But beginning in the sixth century B.C.—or perhaps earlier—and lasting through the nineteenth century, boats were a common feature on the Dead Sea. In fact, the Madaba Mosaic Map, which was discovered in a church in Jordan and dates to the sixth century A.D., depicts two ships loaded with cargo afloat on the lake.

Boats are largely absent on the Dead Sea today, aside from a few tourist and scientific vessels, in part because the area is a military zone and forms part of the international border between Israel and Jordan. But beginning in the sixth century B.C.—or perhaps earlier—and lasting through the nineteenth century, boats were a common feature on the Dead Sea. In fact, the Madaba Mosaic Map, which was discovered in a church in Jordan and dates to the sixth century A.D., depicts two ships loaded with cargo afloat on the lake. Hadas’ recent excavations at Ein Gedi show just how much the community relied on the Dead Sea for both trade and transportation. Almost every excavated house in Ein Gedi contains a slab of red sandstone quarried from the eastern side of the lake, which, says Hadas, may have been used as a cutting board or for sharpening tools. Basalt grinding stones found at the site came from the mountainous region of Moab, also across the water, as did many pieces of painted ceramics. “Of course this came by boat,” Hadas says. “Why would they put it on a camel and walk all the way around when they can just sail across?” Three stone anchors found on Ein Gedi’s shore indicate that larger ships, not just reed boats, were also in use from at least the third or second century B.C.

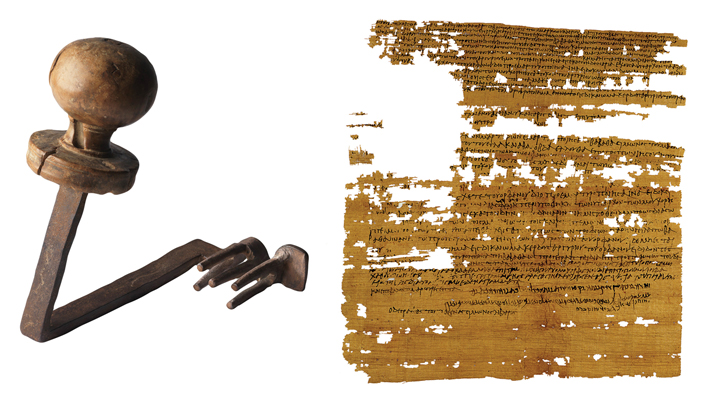

Hadas’ recent excavations at Ein Gedi show just how much the community relied on the Dead Sea for both trade and transportation. Almost every excavated house in Ein Gedi contains a slab of red sandstone quarried from the eastern side of the lake, which, says Hadas, may have been used as a cutting board or for sharpening tools. Basalt grinding stones found at the site came from the mountainous region of Moab, also across the water, as did many pieces of painted ceramics. “Of course this came by boat,” Hadas says. “Why would they put it on a camel and walk all the way around when they can just sail across?” Three stone anchors found on Ein Gedi’s shore indicate that larger ships, not just reed boats, were also in use from at least the third or second century B.C. The Romans took control of the area in the mid-first century B.C., after the defeat of the Hasmoneans by Mark Antony and Herod, and over the next few centuries faced numerous confrontations with local Jewish leaders, including Simeon bar Kokhba, who led a widespread uprising that included residents of Ein Gedi. The Bar Kokhba Revolt ultimately failed in A.D. 135, but, by this time, Ein Gedi was already referred to as a “village of the lord Caesar” in papyrus documents left behind in the so-called Cave of Letters, where dozens of people from the village hid from the fighting between Jewish rebels loyal to bar Kokhba and the Roman military. Some of the papyri Israeli archaeologists found in the cave in the 1960s belonged to a woman named Babata, daughter of Simeon. From documents related to her marriages, divorces, and property ownership, it’s clear that she and her family owned land in Ein Gedi and areas across the water, which had come under Roman control in the second century A.D.

The Romans took control of the area in the mid-first century B.C., after the defeat of the Hasmoneans by Mark Antony and Herod, and over the next few centuries faced numerous confrontations with local Jewish leaders, including Simeon bar Kokhba, who led a widespread uprising that included residents of Ein Gedi. The Bar Kokhba Revolt ultimately failed in A.D. 135, but, by this time, Ein Gedi was already referred to as a “village of the lord Caesar” in papyrus documents left behind in the so-called Cave of Letters, where dozens of people from the village hid from the fighting between Jewish rebels loyal to bar Kokhba and the Roman military. Some of the papyri Israeli archaeologists found in the cave in the 1960s belonged to a woman named Babata, daughter of Simeon. From documents related to her marriages, divorces, and property ownership, it’s clear that she and her family owned land in Ein Gedi and areas across the water, which had come under Roman control in the second century A.D. By the fourth century A.D., the village had expanded farther into the area where Hadas and Peleg-Barkat recently completed their excavations. In the 1970s, the archaeologists who discovered the village’s synagogue determined that it had been extensively renovated in the fifth century A.D., including the addition of a new floor mosaic decorated with geometric designs and birds, as well as with an Aramaic text forbidding community members from revealing “the secret of Ein Gedi.” Hadas can’t say for certain what that secret may have been, although many have surmised that the words refer to guarding the trade secrets of the production of balsam, which was of high value in the ancient world for its aromatic and medicinal properties.

By the fourth century A.D., the village had expanded farther into the area where Hadas and Peleg-Barkat recently completed their excavations. In the 1970s, the archaeologists who discovered the village’s synagogue determined that it had been extensively renovated in the fifth century A.D., including the addition of a new floor mosaic decorated with geometric designs and birds, as well as with an Aramaic text forbidding community members from revealing “the secret of Ein Gedi.” Hadas can’t say for certain what that secret may have been, although many have surmised that the words refer to guarding the trade secrets of the production of balsam, which was of high value in the ancient world for its aromatic and medicinal properties.