From the Trenches

We Are Family

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, August 12, 2019

Fifteen people who were killed in a brutal massacre almost 5,000 years ago and buried together in southern Poland were part of an extended family, genetic analysis has revealed. “The people’s bodies are carefully arranged according to family relationships—mothers are next to their children, and brothers are close to each other,” says Hannes Schroeder, an ancient DNA specialist at the University of Copenhagen. “This shows that they were buried by people who knew them well, most likely by relatives.” Given that adult males are largely missing from the grave, Schroeder adds, they may have been the ones who performed the burial.

Fifteen people who were killed in a brutal massacre almost 5,000 years ago and buried together in southern Poland were part of an extended family, genetic analysis has revealed. “The people’s bodies are carefully arranged according to family relationships—mothers are next to their children, and brothers are close to each other,” says Hannes Schroeder, an ancient DNA specialist at the University of Copenhagen. “This shows that they were buried by people who knew them well, most likely by relatives.” Given that adult males are largely missing from the grave, Schroeder adds, they may have been the ones who performed the burial.

The genetic analysis also showed that all the males in the burial were from a single male lineage, whereas the women and girls were from six different female lineages. This suggests that the family, which belonged to a Neolithic farming culture called the Globular Amphora Culture, was patrilineal, with women leaving their own families to join their male partners. The massacre may have occurred as the result of tensions caused by an influx of pastoralists from the steppes to the east. “We have no way of saying who did the killing,” says Schroeder, “but when you have increased competition for resources it tends to lead to conflict.”

Sowing the Land

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, August 12, 2019

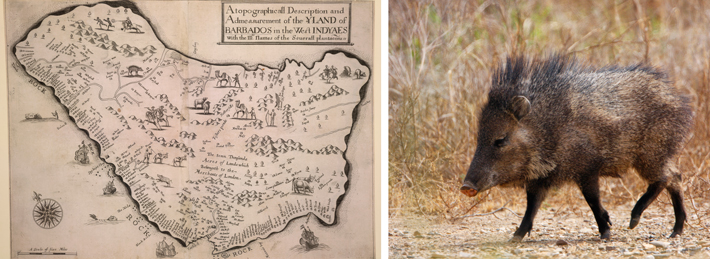

Peccaries, pig-like mammals native to Central and South America, may have been imported to Barbados by Iberian sailors sometime before the 1627 English colonization of the island. While studying a collection of faunal remains held by the Barbados Museum and Historical Society that were excavated in the mid-twentieth century at a colonial domestic site, zooarchaeologist Christina Giovas of Simon Fraser University identified a partial peccary jawbone. The specimen has been radiocarbon dated to between 1645 and 1800, and strontium isotope signatures—which can help determine where a person or animal originated—suggest the peccary spent its whole life on Barbados. Giovas initially suspected that the animal descended from a population introduced by indigenous people who migrated to the island from South America. However, prehistoric human exploitation of animals on Barbados is well documented, she says, and peccaries have never been identified in that record. “The Spanish were aware of the island by the early 1500s,” Giovas explains. “They didn’t settle it, but it’s likely that they stopped by to resupply and acquire fresh water, and in that process probably dropped off peccaries on their way back from South American colonies.” The peccary population may have been hunted to extinction soon after the English arrived.

Peccaries, pig-like mammals native to Central and South America, may have been imported to Barbados by Iberian sailors sometime before the 1627 English colonization of the island. While studying a collection of faunal remains held by the Barbados Museum and Historical Society that were excavated in the mid-twentieth century at a colonial domestic site, zooarchaeologist Christina Giovas of Simon Fraser University identified a partial peccary jawbone. The specimen has been radiocarbon dated to between 1645 and 1800, and strontium isotope signatures—which can help determine where a person or animal originated—suggest the peccary spent its whole life on Barbados. Giovas initially suspected that the animal descended from a population introduced by indigenous people who migrated to the island from South America. However, prehistoric human exploitation of animals on Barbados is well documented, she says, and peccaries have never been identified in that record. “The Spanish were aware of the island by the early 1500s,” Giovas explains. “They didn’t settle it, but it’s likely that they stopped by to resupply and acquire fresh water, and in that process probably dropped off peccaries on their way back from South American colonies.” The peccary population may have been hunted to extinction soon after the English arrived.

Scarab From Space

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Monday, August 12, 2019

Among the treasures discovered in King Tut’s tomb is an elaborate pectoral with a central scarab carved from a canary-yellow material called Libyan Desert glass. Found in the sand dunes of Egypt’s western desert, the glass was formed about 29 million years ago when a quantity of quartz melted at a temperature in excess of 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit, which is hotter than the inside of a volcano. Scholars have long debated whether the yellow glass was created by a meteor that exploded aboveground or by a meteorite impact.

Among the treasures discovered in King Tut’s tomb is an elaborate pectoral with a central scarab carved from a canary-yellow material called Libyan Desert glass. Found in the sand dunes of Egypt’s western desert, the glass was formed about 29 million years ago when a quantity of quartz melted at a temperature in excess of 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit, which is hotter than the inside of a volcano. Scholars have long debated whether the yellow glass was created by a meteor that exploded aboveground or by a meteorite impact.

To test these hypotheses, geologist Aaron Cavosie of Curtin University searched glass samples for grains of the mineral zircon that hadn’t broken down under the intense heat that formed the glass. He identified a small number of preserved zircon grains whose crystal orientation indicated that they had transformed from reidite, a mineral that can only be formed by a meteorite strike. “This provides the first bulletproof evidence that Libyan Desert glass was formed by a meteorite impact,” says Cavosie. No impact crater resulting from such an event has ever been located, he explains, though it may lie beneath shifting dunes or may have eroded to such a degree that it’s no longer distinguishable on the landscape.

A Catalog of Princes

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, August 12, 2019

Luminaries constituting a veritable who’s who of late medieval Europe are depicted on a cache of 10 gold and 24 silver coins found inside a bronze box buried beneath the floor of a late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century house in Dijon, France. Almost all the coins were minted outside France, mainly in locations within the Holy Roman Empire and on the Italian peninsula, according to archaeologists from France’s National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research.

Luminaries constituting a veritable who’s who of late medieval Europe are depicted on a cache of 10 gold and 24 silver coins found inside a bronze box buried beneath the floor of a late fifteenth- or early sixteenth-century house in Dijon, France. Almost all the coins were minted outside France, mainly in locations within the Holy Roman Empire and on the Italian peninsula, according to archaeologists from France’s National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research.

The historical figures portrayed on the coins include some of the continent’s most prominent power brokers: Ercole II d’Este, the duke of Ferrara and grandson of the notorious Pope Alexander VI; the powerful German bishop Philip I of Palatinate; Pope Innocent VIII; and the wealthy Venetian doge Nicolo Tron, among others. Also hidden in the box was a green and white enameled gold pendant typical of wedding medallions, which features the initials V and C interlaced with a gold braid.

Upper Paleolithic Cave Life

By LYDIA PYNE

Monday, August 12, 2019

A rare view of family life some 14,000 years ago has been made possible by recent studies and 3-D modeling of the traces left by a group of five people who walked, crawled, and explored their way through Grotta della Basura in the Liguria region of northern Italy. The cave was originally explored in the 1950s, but an international team of researchers recently modeled 180 footprints, as well as finger- and knee prints. They retraced the movements of the group— two adults, one preadolescent, one six-year-old, and a three-year-old—and reconstructed how they explored the cave. They can be “seen” hugging the cave’s edge, crouching down and walkcrawling where the ceiling drops low, and falling into a single-file line, with the three-year-old at the back, in one of the cave’s narrow chambers. In the chamber farthest from the entrance, called the Room of Mysteries, smears of clay on a stalagmite—a sort of Paleolithic finger painting—were made by the two youngest children.

A rare view of family life some 14,000 years ago has been made possible by recent studies and 3-D modeling of the traces left by a group of five people who walked, crawled, and explored their way through Grotta della Basura in the Liguria region of northern Italy. The cave was originally explored in the 1950s, but an international team of researchers recently modeled 180 footprints, as well as finger- and knee prints. They retraced the movements of the group— two adults, one preadolescent, one six-year-old, and a three-year-old—and reconstructed how they explored the cave. They can be “seen” hugging the cave’s edge, crouching down and walkcrawling where the ceiling drops low, and falling into a single-file line, with the three-year-old at the back, in one of the cave’s narrow chambers. In the chamber farthest from the entrance, called the Room of Mysteries, smears of clay on a stalagmite—a sort of Paleolithic finger painting—were made by the two youngest children.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

The Case for Clotilda

Off the Grid

A God Goes Shopping

Half in the Bag

Herding Genes in Africa

Bronze Age Palace Surfaces

Upper Paleolithic Cave Life

Scarab From Space

A Catalog of Princes

Sowing the Land

We Are Family

Home on the Plains

Saqqara's Working Stiffs

Inner Beauty

Volcano Viewers

Partially Identified Flying Objects

World Roundup

Egyptian watermelons, a Sumatran tsunami, Siege of Yorktown shipwrecks, and the house of the nine-day queen

Artifact

Just a fleeting impression

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement