Digs & Discoveries

The Time Had Come, the Walrus Said

By MARLEY BROWN

Thursday, December 05, 2019

Viking settlers who arrived in Iceland around A.D. 870 may have hunted the island’s native walrus population to extinction in less than 500 years. Radiocarbon dating of walrus skeletal remains excavated at multiple sites indicates that the marine mammals lived continuously along Iceland’s western coast for more than 7,000 years until dying out in the early fourteenth century. According to evolutionary genomicist Morten Tange Olsen of the University of Copenhagen, walruses were valued not only for their meat and blubber, but also, and perhaps primarily, for their tusks. “Given the extensive trade in walrus ivory from Norway and Russia that already existed in the ninth century, it seems plausible that settlers knew its value,” says Olsen. “In fact, some archaeologists and historians have hypothesized that the hunt for walrus was one of the contributing factors to Norse expansion.”

Viking settlers who arrived in Iceland around A.D. 870 may have hunted the island’s native walrus population to extinction in less than 500 years. Radiocarbon dating of walrus skeletal remains excavated at multiple sites indicates that the marine mammals lived continuously along Iceland’s western coast for more than 7,000 years until dying out in the early fourteenth century. According to evolutionary genomicist Morten Tange Olsen of the University of Copenhagen, walruses were valued not only for their meat and blubber, but also, and perhaps primarily, for their tusks. “Given the extensive trade in walrus ivory from Norway and Russia that already existed in the ninth century, it seems plausible that settlers knew its value,” says Olsen. “In fact, some archaeologists and historians have hypothesized that the hunt for walrus was one of the contributing factors to Norse expansion.”

Deerly Departed

By HYUNG-EUN KIM

Thursday, December 05, 2019

While exploring a group of tombs in Haman in southeastern South Korea, archaeologists uncovered a fifth-century A.D. ceremonial earthenware vessel depicting a backward-looking deer, earthenware artifacts in the form of a house and a boat, and other goods. Researchers believe the deer vessel was used as part of a funeral ritual and then buried along with the deceased. A flame-stitch pattern covering the deer’s leg is typical of earthenware from the Gaya Confederacy, an alliance of territories in southern Korea between the first and sixth centuries A.D. Archaeologists also found armor, helmets, and horse fittings that led them to believe the tombs belonged to Gaya leaders.

While exploring a group of tombs in Haman in southeastern South Korea, archaeologists uncovered a fifth-century A.D. ceremonial earthenware vessel depicting a backward-looking deer, earthenware artifacts in the form of a house and a boat, and other goods. Researchers believe the deer vessel was used as part of a funeral ritual and then buried along with the deceased. A flame-stitch pattern covering the deer’s leg is typical of earthenware from the Gaya Confederacy, an alliance of territories in southern Korea between the first and sixth centuries A.D. Archaeologists also found armor, helmets, and horse fittings that led them to believe the tombs belonged to Gaya leaders.

Cretan Coastal Rites

By DANIEL WEISS

Thursday, December 05, 2019

A monumental Minoan building surrounding a 110-foot-long courtyard has been uncovered at Sissi on the northern coast of Crete. Built around 1700 B.C. and featuring finely plastered floors, the structure is similar in size and grandeur to a number of palaces on the island dating to the same period. However, it lacks many typical features of these complexes, including storage rooms, administrative materials, and industrial areas. Archaeologists with the Belgian School at Athens, in collaboration with the Ephorate of Antiquities of Lassithi, did find a range of ritual paraphernalia at the site, offering a clue to what it was used for. “This building was really focused on its central court,” says excavation director Jan Driessen of the Catholic University of Louvain. “It’s quite clear that religious ceremonies took place there.”

A monumental Minoan building surrounding a 110-foot-long courtyard has been uncovered at Sissi on the northern coast of Crete. Built around 1700 B.C. and featuring finely plastered floors, the structure is similar in size and grandeur to a number of palaces on the island dating to the same period. However, it lacks many typical features of these complexes, including storage rooms, administrative materials, and industrial areas. Archaeologists with the Belgian School at Athens, in collaboration with the Ephorate of Antiquities of Lassithi, did find a range of ritual paraphernalia at the site, offering a clue to what it was used for. “This building was really focused on its central court,” says excavation director Jan Driessen of the Catholic University of Louvain. “It’s quite clear that religious ceremonies took place there.”

Nearby, researchers unearthed the tomb of a woman dating to around 1400 B.C. that is typical of the Mycenaeans, who came from mainland Greece around the time she died. The woman was buried with an ivory-handled bronze mirror and a necklace of gold beads. Bone and bronze pins resting on her skeleton appear to have once held the woman’s clothing in place. Hers is the first Mycenaean-style grave to have been found so far east on the island.

Still Standing

By MARLEY BROWN

Thursday, December 05, 2019

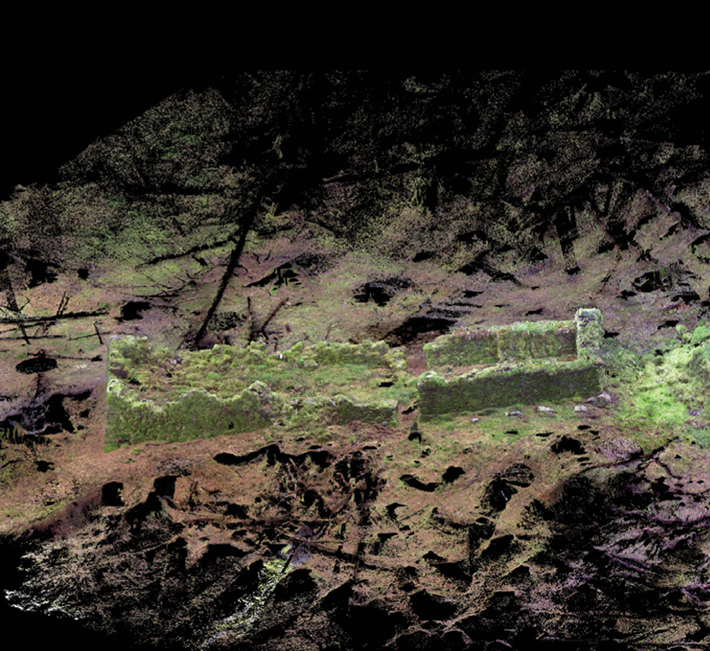

Amid the ruins of two eighteenth-century farmsteads in a forest near Scotland’s Loch Ard, archaeologists have identified buildings that appear to be the remains of an illicit whisky distillery. (When in Scotland, be sure to leave out the “e” in whiskey.) The buildings survive alongside the remnants of kilns for drying corn, which may have been used in the distilled spirits. A number of factors, including the site’s secluded location, its relative proximity to Glasgow, roughly 25 miles south, and its easy access to the loch’s waters, would have made it attractive to illegal whisky producers, says archaeologist Matt Ritchie of Forest and Land Scotland. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, felonious distilling became common in the Scottish Highlands as stills making less than 100 gallons of whisky were banned, and high taxes were imposed on the malted grains used to produce the spirit.

Amid the ruins of two eighteenth-century farmsteads in a forest near Scotland’s Loch Ard, archaeologists have identified buildings that appear to be the remains of an illicit whisky distillery. (When in Scotland, be sure to leave out the “e” in whiskey.) The buildings survive alongside the remnants of kilns for drying corn, which may have been used in the distilled spirits. A number of factors, including the site’s secluded location, its relative proximity to Glasgow, roughly 25 miles south, and its easy access to the loch’s waters, would have made it attractive to illegal whisky producers, says archaeologist Matt Ritchie of Forest and Land Scotland. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, felonious distilling became common in the Scottish Highlands as stills making less than 100 gallons of whisky were banned, and high taxes were imposed on the malted grains used to produce the spirit.

Maya Maize God's Birth

By ZACH ZORICH

Thursday, December 05, 2019

A cache of artifacts found beneath the central plaza at the site of Paso del Macho in the northern part of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula may have been an offering made when the settlement was founded between 900 and 800 B.C. It contains some of the earliest evidence of Maya fertility rituals. Archaeologist Evan Parker of Tulane University, a leader of the ongoing excavation, which is conducted in cooperation with Millsaps College, says that more than 30 artifacts made of greenstone, including small stones that symbolize maize sprouting from the underworld, represent events in the story of the maize god’s birth. This myth was a central part of Maya fertility and rainmaking rituals. The cache also contains several pots painted with images associated with fertility, along with spoons, clamshell pendants, and a large plaque.

A cache of artifacts found beneath the central plaza at the site of Paso del Macho in the northern part of Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula may have been an offering made when the settlement was founded between 900 and 800 B.C. It contains some of the earliest evidence of Maya fertility rituals. Archaeologist Evan Parker of Tulane University, a leader of the ongoing excavation, which is conducted in cooperation with Millsaps College, says that more than 30 artifacts made of greenstone, including small stones that symbolize maize sprouting from the underworld, represent events in the story of the maize god’s birth. This myth was a central part of Maya fertility and rainmaking rituals. The cache also contains several pots painted with images associated with fertility, along with spoons, clamshell pendants, and a large plaque.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Digs & Discoveries

The Man in Prague Castle

Off the Grid

As Told by Herodotus

Bath Buddy

Maya Maize God's Birth

Cretan Coastal Rites

Still Standing

Deerly Departed

The Time Had Come, the Walrus Said

Skoal!

Maya Total War

A Seaside Journey to America

City Limits

Where's the Beef?

Around the World

Rapa Nui moai farmers, the world’s oldest pearl, a rowdy Scottish tavern, and what ancient Assyrian stargazers saw

Artifact

The formula for success

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement