Digs & Discoveries

China's Carp Catchers

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

Members of northern China’s Peiligang culture practiced aquaculture well before the domestication of fish in medieval Europe. By measuring teeth from common carp remains excavated at the Neolithic site of Jiahu, an international team of researchers estimated the body sizes of the fish. Comparing them with carp populations reared in modern Japanese fisheries, they found that the ancient specimens represent both immature and mature fish. This suggests that, by about 8,000 years ago, Jiahu residents had begun to raise carp in controlled channels, where the fish spawned naturally and were harvested in the autumn.

Members of northern China’s Peiligang culture practiced aquaculture well before the domestication of fish in medieval Europe. By measuring teeth from common carp remains excavated at the Neolithic site of Jiahu, an international team of researchers estimated the body sizes of the fish. Comparing them with carp populations reared in modern Japanese fisheries, they found that the ancient specimens represent both immature and mature fish. This suggests that, by about 8,000 years ago, Jiahu residents had begun to raise carp in controlled channels, where the fish spawned naturally and were harvested in the autumn.

A dramatic increase in burials identified at Jiahu around this time indicates that the settlement had grown, explains archaeologist Junzo Uchiyama of the Sainsbury Institute. “It’s possible to assume that carp aquaculture was developed in response to the increase of population,” he says. This innovative approach to food production might have also enabled the Peiligang to expand, as the number of sites associated with the culture increased after 8,300 years ago.

Egyptian Coneheads

By JASON URBANUS

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

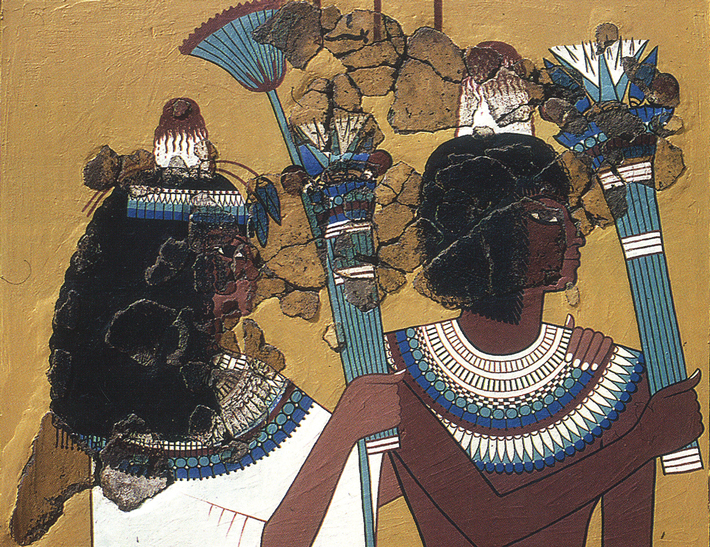

Egyptologists have long been puzzled by a type of figure in ancient Egyptian art depicted wearing an unusual kind of conical hat. These figures often appear in scenes depicting banquets, funerary rituals, or interactions with the gods. Scholars assumed that these strange headpieces were symbolic artistic devices, since no archaeological evidence of them had ever been uncovered. But new excavations of two burials dating to between 1347 and 1332 B.C. in Amarna have yielded proof that these headpieces did, in fact, exist. One hat was found atop the head of a female in her twenties, while the other belonged to a 15-to-20-year-old individual of undetermined sex. Analysis of the cones indicates that they were made of beeswax, perhaps molded around a textile lining. Experts are still unsure why some Egyptians wore the headpieces, or what they represent. “It’s probably wrong to think that there is one definitive answer as to the function and use of the cones,” says Monash University archaeologist Anna Stevens. “It seems that they placed the wearer in a special state, particularly a purified state, which was especially suitable when seeking out the company or assistance of divinities.”

Egyptologists have long been puzzled by a type of figure in ancient Egyptian art depicted wearing an unusual kind of conical hat. These figures often appear in scenes depicting banquets, funerary rituals, or interactions with the gods. Scholars assumed that these strange headpieces were symbolic artistic devices, since no archaeological evidence of them had ever been uncovered. But new excavations of two burials dating to between 1347 and 1332 B.C. in Amarna have yielded proof that these headpieces did, in fact, exist. One hat was found atop the head of a female in her twenties, while the other belonged to a 15-to-20-year-old individual of undetermined sex. Analysis of the cones indicates that they were made of beeswax, perhaps molded around a textile lining. Experts are still unsure why some Egyptians wore the headpieces, or what they represent. “It’s probably wrong to think that there is one definitive answer as to the function and use of the cones,” says Monash University archaeologist Anna Stevens. “It seems that they placed the wearer in a special state, particularly a purified state, which was especially suitable when seeking out the company or assistance of divinities.”

Shock of the Old

By DANIEL WEISS

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

The world’s oldest known cave art created by modern humans, discovered on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi and recently dated to at least 44,000 years ago, has transformed researchers’ understanding of human artistic development. The illustrations feature a number of part-human, part-animal figures hunting wild pigs and dwarf buffaloes. The painting is, therefore, the earliest figurative artwork, the earliest pictorial narrative, and the earliest evidence that people conceived of supernatural beings, which is viewed as a necessary precursor to formulating religious systems of thought. “What is most surprising is that 44,000 years ago all the concepts of art were fully developed,” says archaeologist Maxime Aubert of Griffith University. “They must have had a much earlier origin in Africa, or just after humans left Africa.”

The world’s oldest known cave art created by modern humans, discovered on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi and recently dated to at least 44,000 years ago, has transformed researchers’ understanding of human artistic development. The illustrations feature a number of part-human, part-animal figures hunting wild pigs and dwarf buffaloes. The painting is, therefore, the earliest figurative artwork, the earliest pictorial narrative, and the earliest evidence that people conceived of supernatural beings, which is viewed as a necessary precursor to formulating religious systems of thought. “What is most surprising is that 44,000 years ago all the concepts of art were fully developed,” says archaeologist Maxime Aubert of Griffith University. “They must have had a much earlier origin in Africa, or just after humans left Africa.”

The researchers determined the minimum age of the painting by dating mineral deposits that have formed on top of it. These deposits contain trace amounts of uranium, which decays to thorium at a steady rate. Their age can be calculated from the ratio of the two elements. More than 200 cave art sites have been documented in this region of southern Sulawesi. The newly discovered work is some 65 feet above the cave floor, which helps explain why it escaped notice until recently.

Sailing the Viking Seas

By JASON URBANUS

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

Elaborate ship burials are among the most famous and most mysterious remains of the Viking Age. During the burial ritual, an individual was laid to rest on the deck of a full-size ship, which was then interred beneath a mound of earth. Over the past century and a half, dozens of such ship burials have been discovered from Scandinavia to the British Isles. In recent months, five more have been identified in Norway and Sweden.

Elaborate ship burials are among the most famous and most mysterious remains of the Viking Age. During the burial ritual, an individual was laid to rest on the deck of a full-size ship, which was then interred beneath a mound of earth. Over the past century and a half, dozens of such ship burials have been discovered from Scandinavia to the British Isles. In recent months, five more have been identified in Norway and Sweden.

Specialists from the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research detected one ship on the Norwegian island of Edoya using high-resolution georadar. The vessel, which lies just belowground, is between 40 and 50 feet long and awaits further archaeological investigation. Around 25 miles east of Edoya, on Norway’s mainland, archaeologists were perplexed by the discovery of not one, but two ship burials at a single site in Vinjeora. The first contained a man who died in the eighth century a.d. and was buried in a 30-foot boat. Around 100 years later, a well-to-do woman was buried in her own, slightly smaller ship, directly on top of the earlier burial. Her grave contained several high-quality artifacts, including a cross-shaped brooch. “We were very surprised,” says archaeologist Raymond Sauvage of the Norwegian University of Science and Technology. “I know of no other examples where they reopened an earlier grave to bury a new boat in the next century.”

Sauvage believes the two must have been related, perhaps as grandfather and granddaughter. Across the border in Sweden, two additional Viking ship burials were recently unearthed outside the town of Uppsala. While one was found to have been badly damaged, the other was well-preserved. It contained a man who was sent to the afterlife with the companionship of a horse and a dog, both of which were also interred in the ship.

Domestic Harmony

By MARLEY BROWN

Tuesday, February 11, 2020

A fragmentary but poignant insight into the spare moments of nineteenth-century Wisconsin homesteaders has been discovered at Fort McCoy, a United States Army installation about 90 miles northwest of Madison. Archaeologists unearthed four pieces of a German-made harmonica among more than 2,000 artifacts from what appears to have been a communal dumping ground in the area. One of the harmonica’s exterior plates reads “Friedr. Hotz,” indicating that it was made by the Friedrich Hotz Company. Based in Knittlingen, Germany, the company began producing harmonicas in the 1820s and was eventually bought out by Matthias Hohner, who introduced the instrument to America in 1862. “The leisure-related items from the site represent a small portion of the assemblage,” says Colorado State University archaeologist Tyler Olsen. “This probably reflects the proportion of any given day that could be devoted to recreation in some small way.”

A fragmentary but poignant insight into the spare moments of nineteenth-century Wisconsin homesteaders has been discovered at Fort McCoy, a United States Army installation about 90 miles northwest of Madison. Archaeologists unearthed four pieces of a German-made harmonica among more than 2,000 artifacts from what appears to have been a communal dumping ground in the area. One of the harmonica’s exterior plates reads “Friedr. Hotz,” indicating that it was made by the Friedrich Hotz Company. Based in Knittlingen, Germany, the company began producing harmonicas in the 1820s and was eventually bought out by Matthias Hohner, who introduced the instrument to America in 1862. “The leisure-related items from the site represent a small portion of the assemblage,” says Colorado State University archaeologist Tyler Olsen. “This probably reflects the proportion of any given day that could be devoted to recreation in some small way.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Digs & Discoveries

Ancient Academia

Off the Grid

Bicycles and Bayonets

A Barrel of Bronze Age Monkeys

Domestic Harmony

Shock of the Old

Sailing the Viking Seas

Egyptian Coneheads

China's Carp Catchers

Field of Tombs

Bird on a Wire

Tool Time

Protecting the Young

Early Adopters

Around the World

Neolithic chewing gum DNA, the first sled dogs, and swelling the ranks of the Terracotta Army

Artifact

Ahead of the curve

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement