The Age of Pictures

May/June 2020

During the Civil War, soldiers were able to send pictures of themselves home for the first time in history. Therefore, it was not surprising to find that photographs were being taken at Camp Nelson. Prior to his recent excavations, Camp Nelson National Monument archaeologist Stephen McBride had found documentary evidence of at least four photographers working at the camp. One was G.W. Foster, who was contracted by the army and took photos to send with military reports to show how orderly the camp was.

During the Civil War, soldiers were able to send pictures of themselves home for the first time in history. Therefore, it was not surprising to find that photographs were being taken at Camp Nelson. Prior to his recent excavations, Camp Nelson National Monument archaeologist Stephen McBride had found documentary evidence of at least four photographers working at the camp. One was G.W. Foster, who was contracted by the army and took photos to send with military reports to show how orderly the camp was.

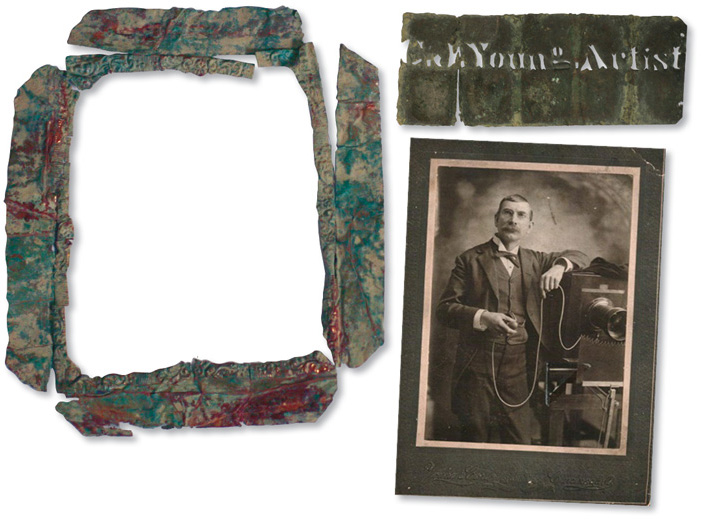

The newly discovered photo studio has added Cassius Jones (“C.J.”) Young, the son of a Lexington portrait painter, to the list of Camp Nelson’s photographers. “The fact that we have so many photographers working at the camp really speaks to the prevalence and popularity of photography in the Civil War,” McBride says. McBride identified Young’s studio based on the brass stencils that he used to sign his work, most of which contained some kind of error and were likely discarded practice plates. His team also found brass sheets used to make stencils for soldiers’ photos, which were marked with their name, unit, and company, as well as mats, glass plates, and chemicals for the developing process.

It was, of course, not only soldiers whose pictures were taken during the 1860s. “One of the most photographed people of the era was Frederick Douglass,” says McBride. “Douglass wrote several articles on photography and called the era the ‘Age of Pictures.’ He thought that photography was an important social development because only people, not animals, could appreciate photographs. Soldiers and recently emancipated men were Americans, and they wanted to document their new status and to share it. A photo meant you were a person, and thus that African Americans were people, too.”