Features

Idol of the Painted Temple

By MARLEY BROWN

Monday, August 03, 2020

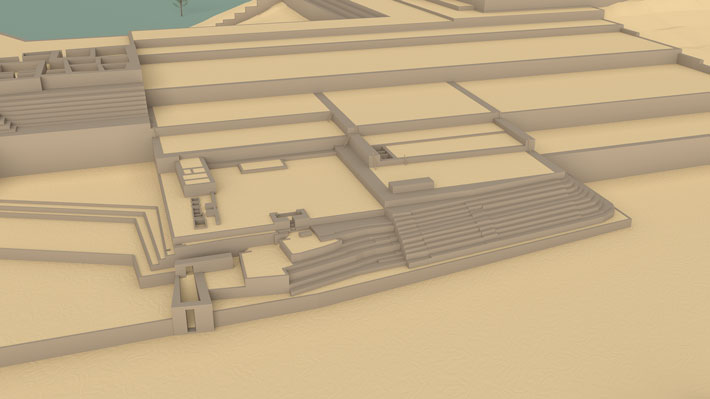

After defeating the forces of Atahualpa, the last Inca emperor, in 1533, Francisco Pizarro dispatched his brother Hernando to a vast religious center on Peru’s central coast called Pachacamac. Just south of modern-day Lima, Pachacamac spanned nearly 1,500 acres and had, by that time, been a place of worship for at least 1,000 years. There, in front of an assembled crowd of locals and priests, Hernando Pizarro is said to have smashed an idol representing one of Pachacamac’s primary deities. The Spanish had introduced a sweeping proscription against indigenous religious practice and forced the local population to convert to Christianity. Pachacamac was soon abandoned, ending a centuries-long tradition of venerating cults at the site under the rule of elites of multiple Andean cultures. These various cultures, evidence suggests, shared spiritual ideas and perhaps even gods. Pachacamac is, in fact, an Inca name for an oracle that may have been worshipped in some form for hundreds of years before the Inca Empire conquered the area in the late fifteenth century.

Just over 400 years after Pizarro’s raid on Pachacamac, in 1938, avocational archaeologist Albert Giesecke discovered a wooden sculpture roughly eight feet tall and five inches in diameter hidden among rubble from what was once the north atrium of Pachacamac’s Painted Temple. The pyramidal Painted Temple is believed to have first been built in the eighth and ninth centuries A.D. and then to have been expanded during the Andean Late Intermediate period (ca. A.D. 1000–1470), when Pachacamac was home to a chieftainship and a deity both known as Ychsma. An American polymath trained in economics who first traveled to Peru in 1909 as an adviser to the Peruvian government, Giesecke became an influential public servant and a champion of the country’s pre-Columbian heritage. With information that had been provided to him by farmers in the area, Giesecke tipped off explorer Hiram Bingham to the location of ruins high above a gorge in the southern highlands—a site now known as Machu Picchu.

Since its discovery, the sculpture from the Painted Temple has been called the Pachacamac Idol and has been the subject of intense interest—and controversy—among scholars of the Andean world. Many have speculated as to whether this idol could be the very artifact Hernando Pizarro is said to have destroyed.

A Silk Road Renaissance

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, July 14, 2020

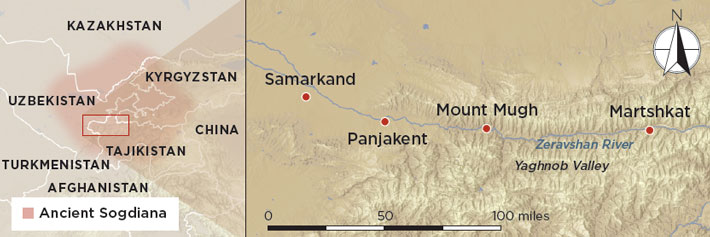

The Silk Road, the vast network of trade routes that connected China to the rest of Eurasia from roughly the first century B.C. to A.D. 1400, was justly famous in the West for the rich silk textiles it carried to the Mediterranean world. “But it could just as easily have been called the Jade Road, the Glass Road, or even the Rhubarb Road,” says art historian Judith Lerner of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University. Such was the variety of commodities—raw silk, glass, spices, finished metalwork, ceramics, and much more—that any one of dozens of goods could have given the route its name. The Sacred Road, too, might once have been a fitting appellation. Christian and Buddhist missionaries, among others, used Silk Road caravans to cross the Asian continent. And from the fifth to the eighth century A.D., the overland trade routes that crossed through Central Asia might also have been called the Sogdian Road. An East Iranian people who lived in what is now Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, the Sogdians were, for a time, the leading merchants of the Silk Road. “The Sogdians achieved great influence via trade,” says Lerner. “The Chinese even had a saying: ‘When a Sogdian child is born, his mother puts honey on his tongue so that he will speak sweetly and glue on his palm so that money will stick to it.’”

The Silk Road, the vast network of trade routes that connected China to the rest of Eurasia from roughly the first century B.C. to A.D. 1400, was justly famous in the West for the rich silk textiles it carried to the Mediterranean world. “But it could just as easily have been called the Jade Road, the Glass Road, or even the Rhubarb Road,” says art historian Judith Lerner of the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University. Such was the variety of commodities—raw silk, glass, spices, finished metalwork, ceramics, and much more—that any one of dozens of goods could have given the route its name. The Sacred Road, too, might once have been a fitting appellation. Christian and Buddhist missionaries, among others, used Silk Road caravans to cross the Asian continent. And from the fifth to the eighth century A.D., the overland trade routes that crossed through Central Asia might also have been called the Sogdian Road. An East Iranian people who lived in what is now Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, the Sogdians were, for a time, the leading merchants of the Silk Road. “The Sogdians achieved great influence via trade,” says Lerner. “The Chinese even had a saying: ‘When a Sogdian child is born, his mother puts honey on his tongue so that he will speak sweetly and glue on his palm so that money will stick to it.’”

The Sogdians were more than quick-witted intermediaries. At their height, their sophisticated culture, skilled diplomacy, and mercantile power helped shape the greater world around them. “You could describe the Sogdians as the first internationalists or globalists,” says Lerner. Sogdian diplomats, translators, artists, craftspeople, and entertainers traveled in the caravans that ventured along the Silk Road and settled in merchant colonies along the route in Central Asia and China. Sogdian was the lingua franca of the Silk Road, and, for a time, a vogue for all things Sogdian swept Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618–906) China. Chinese courtiers and concubines adopted Sogdian fashions, and the many Tang Dynasty depictions of Sogdian musicians suggest their performances were in high demand. For a time, a craze for an ecstatic dance known as the “Sogdian Whirl” swept the country, and Sogdian dancers became a popular motif in Chinese art that lasted long after Sogdians themselves had been assimilated. Indeed, in the mid-eighth century, a half-Sogdian general named An Lushan, who was reputed to weigh 400 pounds, was known for delighting the Chinese imperial court with his version of the Sogdian Whirl. In turn, the people of Sogdiana were highly receptive to outside ideas, religions, and artistic styles from China, India, and even the Byzantine Empire.

At home in Central Asia, the Sogdians lived in a number of independent city-states clustered around the Zeravshan Valley and the oases of modern-day Uzbekistan. “These states can be compared to the Italian city-states of the Renaissance, each with its own ruling family, laws, and government,” says Lerner. “In fact, the analogy can be taken further when we think of these cities’ rulers as ‘merchant princes’ since that is how the Sogdians derived their wealth.” Samarkand was one of the largest and most prosperous of these cities. Some 60 miles to the east, the much smaller city of Panjakent was a satellite of sorts to Samarkand, but supported its own vibrant economy.

|

Slideshow:

|

Murals of the Silk Road

|

From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World

By LYDIA PYNE

Tuesday, June 09, 2020

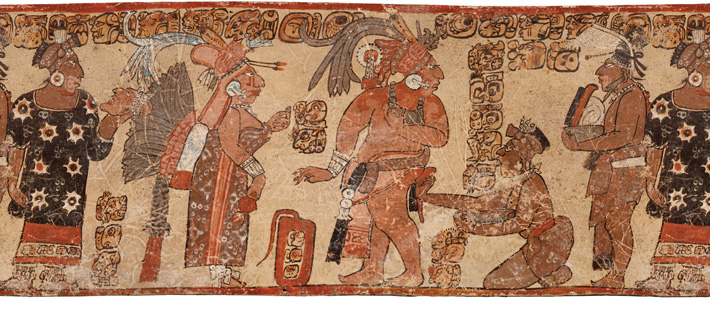

How people dress and adorn themselves has long been a primary way of showcasing their identity and communicating it to others. The ancient Maya, whose world was one of vivid cultural practices and strict hierarchy, with rulers playing an essential role mediating between the gods and mere mortals, developed a deep interest in status and display. One of the ways this manifested itself was in their rich array of clothing and personal ornamentation. “For the Classic Maya, in many ways, clothing defined personhood,” says Alyce de Carteret, a fellow in Art of the Ancient Americas at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Numerous aspects of an individual’s identity—from their political position, to their trade, to their gender—were communicated through adornment, and depictions of clothed bodies encode this vital information. To study ancient Maya dress, then, is to study ancient Maya society itself.”

How people dress and adorn themselves has long been a primary way of showcasing their identity and communicating it to others. The ancient Maya, whose world was one of vivid cultural practices and strict hierarchy, with rulers playing an essential role mediating between the gods and mere mortals, developed a deep interest in status and display. One of the ways this manifested itself was in their rich array of clothing and personal ornamentation. “For the Classic Maya, in many ways, clothing defined personhood,” says Alyce de Carteret, a fellow in Art of the Ancient Americas at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. “Numerous aspects of an individual’s identity—from their political position, to their trade, to their gender—were communicated through adornment, and depictions of clothed bodies encode this vital information. To study ancient Maya dress, then, is to study ancient Maya society itself.”

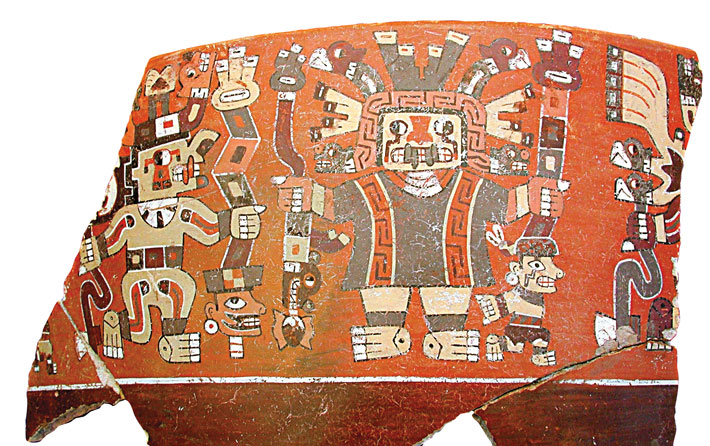

By the second millennium B.C., the Maya occupied much of southern and eastern Mesoamerica, including all of the Yucatan Peninsula, Belize, and Guatemala, as well as western Honduras and El Salvador and parts of the Mexican states of Tabasco and Chiapas. Their world was not a unified empire, but rather a collection of kingdoms based in cities such as Copan, Palenque, and Chichen Itza. At various times, new power centers emerged, and their leaders pursued ambitious architectural projects whose remains still impress today, while older centers declined. Much of the scholarship on ancient Maya clothing and adornment focuses on the Classic period (A.D. 250–900), when the Maya population grew dramatically, and royal courts, with their flamboyant ritual displays, became more prominent. While few items of clothing and ornamentation have been preserved in the archaeological record, scholars use depictions on painted murals, ceramic vessels, stone stelas, and clay figurines dating to this period to learn what the ancient Maya wore.

By the second millennium B.C., the Maya occupied much of southern and eastern Mesoamerica, including all of the Yucatan Peninsula, Belize, and Guatemala, as well as western Honduras and El Salvador and parts of the Mexican states of Tabasco and Chiapas. Their world was not a unified empire, but rather a collection of kingdoms based in cities such as Copan, Palenque, and Chichen Itza. At various times, new power centers emerged, and their leaders pursued ambitious architectural projects whose remains still impress today, while older centers declined. Much of the scholarship on ancient Maya clothing and adornment focuses on the Classic period (A.D. 250–900), when the Maya population grew dramatically, and royal courts, with their flamboyant ritual displays, became more prominent. While few items of clothing and ornamentation have been preserved in the archaeological record, scholars use depictions on painted murals, ceramic vessels, stone stelas, and clay figurines dating to this period to learn what the ancient Maya wore.

Many of these images show the Maya engaging in or preparing for religious ceremonies, which were scheduled based on an extremely complex calendar system and called for specialized clothing and accessories, from elaborate headdresses to ornate sandals, and even patterns painted directly on the skin. Other images portray warriors or ballplayers, who often integrated animals into their outfits. Still others depict resplendently costumed rulers towering over naked captives. Maya adornment incorporated a broad range of materials, from the luxurious blue-green feathers of the quetzal bird to the spotted skin of the jaguar, which was sometimes worn as a cape with head and paws still attached. Even a seemingly mundane substance such as paper made from bark, when crafted into a simple headband, played a key role in one of the most important Maya rituals of all. And when fashioned into earrings, this paper helped facilitate the Maya ceremonial practice of self-sacrifice. “All these examples point to something deeper and more complex than the material culture of clothing alone can convey,” says Astrid Runggaldier, an archaeologist and assistant director of the Mesoamerican Center at the University of Texas at Austin. “They hint at the role of attire as accoutrement to the social roles embodied by human beings.”

Lydia Pyne is a writer based in Austin, Texas.

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World

A Silk Road Renaissance

Idol of the Painted Temple

Letter from Normandy

Digs & Discoveries

The Emperor of Stones

Off the Grid

Ice Age Ice Box

Sticking Its Neck Out

ID'ing England's First Nun

Play Ball!

History in Ice

Roman River Cruiser

Prized Polo...Donkeys?

Twisted Neanderthal Tech

Around the World

Prehistoric Floridian fishermen, Hannibal’s army in Spain, Paleolithic mystery spheres, and a lost Maya city

Artifact

A Roman soldier’s gift to the gods

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Other scholars argue that the transformation that eventually led to the construction of Pachacamac’s temples and its rise as a religious center had taken place centuries before, in the Early Intermediate period (ca. 200 B.C.–A.D. 650), and that the site was already at that point home to a state-level society with a stratified class system, including military and priestly castes, and had a well-developed material culture of its own. This society, in turn, may have adopted cultural practices from, traded with, or become a client state of Wari. While direct evidence of Wari political or military control at Pachacamac is lacking, numerous Wari-influenced burials, ceramics, murals, and textiles have been discovered at the site, particularly in and around the vicinity of the Painted Temple.

Other scholars argue that the transformation that eventually led to the construction of Pachacamac’s temples and its rise as a religious center had taken place centuries before, in the Early Intermediate period (ca. 200 B.C.–A.D. 650), and that the site was already at that point home to a state-level society with a stratified class system, including military and priestly castes, and had a well-developed material culture of its own. This society, in turn, may have adopted cultural practices from, traded with, or become a client state of Wari. While direct evidence of Wari political or military control at Pachacamac is lacking, numerous Wari-influenced burials, ceramics, murals, and textiles have been discovered at the site, particularly in and around the vicinity of the Painted Temple. While scholars cannot say for certain what the Pachacamac Idol was called by those who venerated it, it does not appear to depict one of the primary Wari deities. Wari are thought to have worshipped a trio of gods headed by the Staff God, a humanlike figure typically portrayed holding a staff in each hand, with solar rays radiating from around his face. In many instances, he is shown accompanied by two attendants who also hold staffs. Isbell says that if the Pachacamac Idol does represent a Wari deity, it does so in a unique manner. “If it were dead-on Wari style, it would show a recognizable figure from that pantheon—and it doesn’t,” he says. “On the other hand, certain decorative elements it does have, such as pendent rays and feline heads, are very reminiscent of the rays that come off the face of the Staff God.”

While scholars cannot say for certain what the Pachacamac Idol was called by those who venerated it, it does not appear to depict one of the primary Wari deities. Wari are thought to have worshipped a trio of gods headed by the Staff God, a humanlike figure typically portrayed holding a staff in each hand, with solar rays radiating from around his face. In many instances, he is shown accompanied by two attendants who also hold staffs. Isbell says that if the Pachacamac Idol does represent a Wari deity, it does so in a unique manner. “If it were dead-on Wari style, it would show a recognizable figure from that pantheon—and it doesn’t,” he says. “On the other hand, certain decorative elements it does have, such as pendent rays and feline heads, are very reminiscent of the rays that come off the face of the Staff God.”

The idol may have taken on a meaning recognizable to multiple Andean cultures during the Middle Horizon period (ca. A.D. 650–1000) through its style, color, and decoration, or through a shared understanding of spiritual or religious symbols. It probably endured as an object of worship because new rulers who took control at Pachacamac, such as the Inca, tended to tolerate existing cults. “The Inca were interested in integrating local and regional cults into their own pantheon and sacred net,” says Eeckhout. “It was part of their conquest strategy, but also their belief in the reality of the powers of those entities.” Centuries before, Wari also appear not only to have allowed the people at Pachacamac to continue to worship their local deities, but those gods—including the deity represented on the Pachacamac Idol—may even have been incorporated as lesser members of the Wari pantheon.

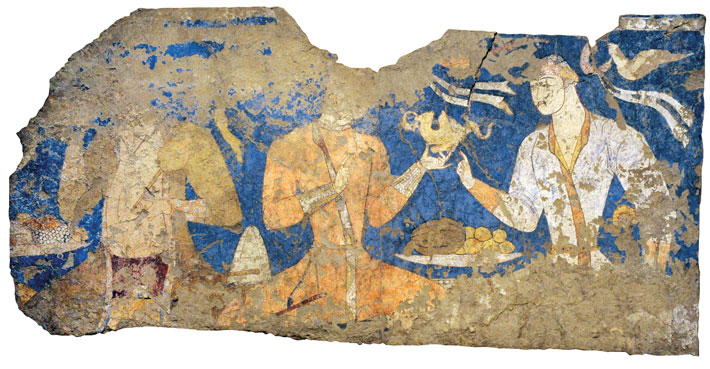

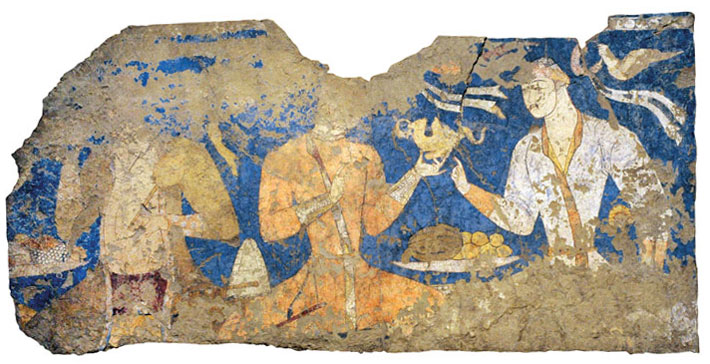

The idol may have taken on a meaning recognizable to multiple Andean cultures during the Middle Horizon period (ca. A.D. 650–1000) through its style, color, and decoration, or through a shared understanding of spiritual or religious symbols. It probably endured as an object of worship because new rulers who took control at Pachacamac, such as the Inca, tended to tolerate existing cults. “The Inca were interested in integrating local and regional cults into their own pantheon and sacred net,” says Eeckhout. “It was part of their conquest strategy, but also their belief in the reality of the powers of those entities.” Centuries before, Wari also appear not only to have allowed the people at Pachacamac to continue to worship their local deities, but those gods—including the deity represented on the Pachacamac Idol—may even have been incorporated as lesser members of the Wari pantheon. Today, the mudbrick ruins of Panjakent’s citadel, palaces, and temples survive behind formidable city walls that rise about three miles from the banks of the Zeravshan River in the present-day Sughd—itself the Sogdian word for Sogdiana—province of northern Tajikistan. For more than 70 years, excavations carried out there almost continuously by Soviet and then Russian and Tajik archaeologists have revealed the rich texture of Sogdian city life. Though several Sogdian cities have been excavated, much of what scholars know about Sogdiana is based on documents and artifacts recovered from towns along the Silk Road and in China. The excavations in Panjakent, now under the supervision of archaeologist and philologist Pavel Lurje of the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, offer a vivid glimpse of what the Sogdians were like in their homeland. In particular, dramatic murals depicting myths, fables, and everyday scenes characterize the world of the Sogdian imagination. “We find murals in almost every field season,” says Lurje. “It’s one of the reasons archaeologists have worked at the site for so many years.” Aleksandr Naymark, an archaeologist at Hofstra University who excavated at the site in the 1980s, says that the analogy of Sogdian merchants to Renaissance Italians is especially fitting given the dizzying array of murals that have been unearthed at Panjakent. “In northern Italy during the Renaissance you had this merchant class whose extreme wealth led to an exceptionally creative period, especially in narrative art,” says Naymark. “The Sogdian merchants enabled the same kind of burst of creativity, which you see in these murals.”

Today, the mudbrick ruins of Panjakent’s citadel, palaces, and temples survive behind formidable city walls that rise about three miles from the banks of the Zeravshan River in the present-day Sughd—itself the Sogdian word for Sogdiana—province of northern Tajikistan. For more than 70 years, excavations carried out there almost continuously by Soviet and then Russian and Tajik archaeologists have revealed the rich texture of Sogdian city life. Though several Sogdian cities have been excavated, much of what scholars know about Sogdiana is based on documents and artifacts recovered from towns along the Silk Road and in China. The excavations in Panjakent, now under the supervision of archaeologist and philologist Pavel Lurje of the State Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, offer a vivid glimpse of what the Sogdians were like in their homeland. In particular, dramatic murals depicting myths, fables, and everyday scenes characterize the world of the Sogdian imagination. “We find murals in almost every field season,” says Lurje. “It’s one of the reasons archaeologists have worked at the site for so many years.” Aleksandr Naymark, an archaeologist at Hofstra University who excavated at the site in the 1980s, says that the analogy of Sogdian merchants to Renaissance Italians is especially fitting given the dizzying array of murals that have been unearthed at Panjakent. “In northern Italy during the Renaissance you had this merchant class whose extreme wealth led to an exceptionally creative period, especially in narrative art,” says Naymark. “The Sogdian merchants enabled the same kind of burst of creativity, which you see in these murals.” That world began to disappear in the eighth century. In 755, General An Lushan of Sogdian Whirl fame led a coup against the Chinese emperor that nearly succeeded. Its failure, however, heralded the end of Sogdian influence in China. At the same time, a slow-moving Arab invasion of Central Asia had already nearly erased Sogdiana from the map, and its inhabitants were soon largely forgotten. Lurje’s excavations at Panjakent and at a second, much more remote site known as Hisorak, offer a unique vantage point on Sogdian culture, both in its heyday and when it was close to vanishing.

That world began to disappear in the eighth century. In 755, General An Lushan of Sogdian Whirl fame led a coup against the Chinese emperor that nearly succeeded. Its failure, however, heralded the end of Sogdian influence in China. At the same time, a slow-moving Arab invasion of Central Asia had already nearly erased Sogdiana from the map, and its inhabitants were soon largely forgotten. Lurje’s excavations at Panjakent and at a second, much more remote site known as Hisorak, offer a unique vantage point on Sogdian culture, both in its heyday and when it was close to vanishing. The discovery of such a spectacular collection of documents in Sogdiana, still the only such archive to have been found in the Sogdian homeland, prompted the Soviet archaeologists to turn their attention to Panjakent proper, where they began excavating in 1947. They discovered that a citadel had existed at the site from perhaps the second century B.C., but that the city itself dated to around the beginning of the fifth century A.D. when the residents of Panjakent erected a massive 30-foot wall, perhaps to protect it from nomadic incursions. Thereafter the city grew rapidly around carefully planned streets and lanes and became a densely occupied urban landscape, with two- and three-story buildings becoming the rule. “It’s a real mudbrick jungle,” says Lurje. “You have homes connected to shops that have separate entrances, but everything was quite close and people were living on top of one another.”

The discovery of such a spectacular collection of documents in Sogdiana, still the only such archive to have been found in the Sogdian homeland, prompted the Soviet archaeologists to turn their attention to Panjakent proper, where they began excavating in 1947. They discovered that a citadel had existed at the site from perhaps the second century B.C., but that the city itself dated to around the beginning of the fifth century A.D. when the residents of Panjakent erected a massive 30-foot wall, perhaps to protect it from nomadic incursions. Thereafter the city grew rapidly around carefully planned streets and lanes and became a densely occupied urban landscape, with two- and three-story buildings becoming the rule. “It’s a real mudbrick jungle,” says Lurje. “You have homes connected to shops that have separate entrances, but everything was quite close and people were living on top of one another.”

Sometimes the murals seem to reflect the personalities or occupations of those who commissioned them. In one house, where archaeologists found a number of bone gambling pieces, they also unearthed a mural depicting a scene from the Indian epic the Mahabharata, which shows the legendary king Virata playing backgammon, a game often associated with gambling. Another house, whose collection of unusually large granaries suggests its owner was a grain merchant, contained a mural depicting a harvest ceremony.

Sometimes the murals seem to reflect the personalities or occupations of those who commissioned them. In one house, where archaeologists found a number of bone gambling pieces, they also unearthed a mural depicting a scene from the Indian epic the Mahabharata, which shows the legendary king Virata playing backgammon, a game often associated with gambling. Another house, whose collection of unusually large granaries suggests its owner was a grain merchant, contained a mural depicting a harvest ceremony. Perhaps the most spectacular mural was excavated at a midsize house in the southeastern section of the city. There, archaeologists discovered what they dubbed the Blue Hall, a banquet space with built-in benches along the walls. The surfaces of these walls were covered with intricate, 15-foot-high murals divided into horizontal sections. A top section depicts a religious ceremony, perhaps a family ritual. The middle and largest section shows scenes from the national epic of Iranian peoples, the Shahnameh, or “Book of Kings,” which was first written down around the year 1000, almost 300 years after the mural was painted. The mural depicts the feats of the hero Rustam as he leads an army to battle demons. Below the stories of Rustam is a smaller set of murals that illustrate a series of animal fables, which were popular in Panjakent. A mural discovered in another house even depicts the tale of the “Goose Who Laid the Golden Egg,” famous in the West from Aesop’s Fables. What remains of the Sogdians’ written culture is mostly religious and administrative in nature. But they surely had a rich literature as well, which may be partly reflected in these murals. “We know they had books,” says Lerner. “There’s a mid-eighth-century painting from Panjakent of a large illustrated codex. It’s possible that the tales and fables we see painted in the lower registers of the banquet rooms in Panjakent’s houses were also written and illustrated in bound or folded books.” Some of the scenes may reflect oral traditions, perhaps ones that Sogdians could tell while feasting and looking at the murals. Other stories may have reached Panjakent on painted scrolls.

Perhaps the most spectacular mural was excavated at a midsize house in the southeastern section of the city. There, archaeologists discovered what they dubbed the Blue Hall, a banquet space with built-in benches along the walls. The surfaces of these walls were covered with intricate, 15-foot-high murals divided into horizontal sections. A top section depicts a religious ceremony, perhaps a family ritual. The middle and largest section shows scenes from the national epic of Iranian peoples, the Shahnameh, or “Book of Kings,” which was first written down around the year 1000, almost 300 years after the mural was painted. The mural depicts the feats of the hero Rustam as he leads an army to battle demons. Below the stories of Rustam is a smaller set of murals that illustrate a series of animal fables, which were popular in Panjakent. A mural discovered in another house even depicts the tale of the “Goose Who Laid the Golden Egg,” famous in the West from Aesop’s Fables. What remains of the Sogdians’ written culture is mostly religious and administrative in nature. But they surely had a rich literature as well, which may be partly reflected in these murals. “We know they had books,” says Lerner. “There’s a mid-eighth-century painting from Panjakent of a large illustrated codex. It’s possible that the tales and fables we see painted in the lower registers of the banquet rooms in Panjakent’s houses were also written and illustrated in bound or folded books.” Some of the scenes may reflect oral traditions, perhaps ones that Sogdians could tell while feasting and looking at the murals. Other stories may have reached Panjakent on painted scrolls. While excavating at Panjakent, Lurje and his team have also worked more than 100 miles upriver, at the site of Hisorak, which he has identified as Martshkat, a small Sogdian city mentioned at least seven times in the Mount Mugh archive. Since 2010, he has led excavations at Martshkat, which consisted of a settlement perched above a river gorge and attached to three mudbrick citadels. While some of the city’s buildings were decorated with murals, only fragmentary traces remain. Instead, the unusual chemistry of the soil has preserved other types of artifacts, especially goat and sheep skins. According to the Mount Mugh documents, the city was well known for producing leather from such hides. One document even mentions the name of the attendant, Wakhshmareg, who was responsible for the large basin used to tan the skins. Lurje believes he has identified this very basin in a large courtyard in the settlement. He has also unearthed several fragments of Sogdian writing preserved on sticks of wood. People were living at Martshkat as early as the first century A.D., but it appears the settlement expanded around the beginning of the eighth century, when the Arabs began to take power in Central Asia. Indeed, one of the Mount Mugh documents that mentions the city comes from an unnamed ruler asking for aid in recapturing workers who had absconded while building an important structure in the town. Lurje speculates that these men were working on one of the citadels, possibly in anticipation of a siege by Arab forces.

While excavating at Panjakent, Lurje and his team have also worked more than 100 miles upriver, at the site of Hisorak, which he has identified as Martshkat, a small Sogdian city mentioned at least seven times in the Mount Mugh archive. Since 2010, he has led excavations at Martshkat, which consisted of a settlement perched above a river gorge and attached to three mudbrick citadels. While some of the city’s buildings were decorated with murals, only fragmentary traces remain. Instead, the unusual chemistry of the soil has preserved other types of artifacts, especially goat and sheep skins. According to the Mount Mugh documents, the city was well known for producing leather from such hides. One document even mentions the name of the attendant, Wakhshmareg, who was responsible for the large basin used to tan the skins. Lurje believes he has identified this very basin in a large courtyard in the settlement. He has also unearthed several fragments of Sogdian writing preserved on sticks of wood. People were living at Martshkat as early as the first century A.D., but it appears the settlement expanded around the beginning of the eighth century, when the Arabs began to take power in Central Asia. Indeed, one of the Mount Mugh documents that mentions the city comes from an unnamed ruler asking for aid in recapturing workers who had absconded while building an important structure in the town. Lurje speculates that these men were working on one of the citadels, possibly in anticipation of a siege by Arab forces. That siege appears never to have taken place, and people continued to live in Martshkat in reduced numbers until perhaps the tenth century, but it’s difficult to say exactly for how long. While some 3,000 coins have been unearthed at Panjakent, only three have been found at Martshkat, a sign perhaps that this city was at a remove from the bustling Silk Road economies that characterized Sogdian settlements in the Zeravshan Valley and the oases beyond.

That siege appears never to have taken place, and people continued to live in Martshkat in reduced numbers until perhaps the tenth century, but it’s difficult to say exactly for how long. While some 3,000 coins have been unearthed at Panjakent, only three have been found at Martshkat, a sign perhaps that this city was at a remove from the bustling Silk Road economies that characterized Sogdian settlements in the Zeravshan Valley and the oases beyond.