Digs & Discoveries

Twisted Neanderthal Tech

By ZACH ZORICH

Tuesday, June 09, 2020

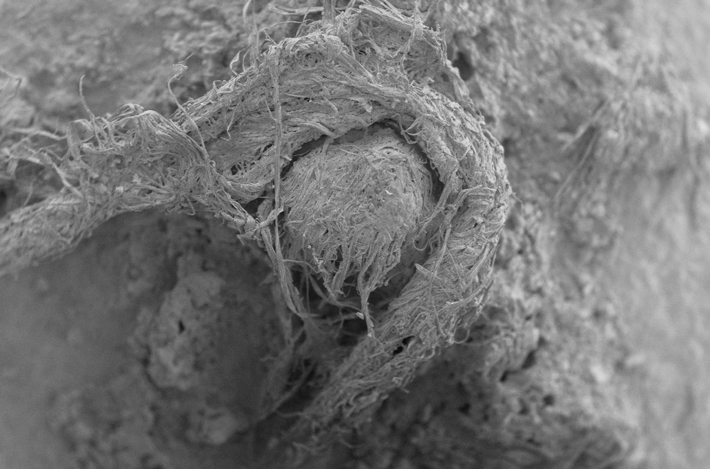

More than 40,000 years ago, Neanderthals living at the site of Abri du Maras in southeastern France made what is the earliest known piece of cord. This apparently simple technology is now providing insights into the workings of the Neanderthal mind, says archaeologist Bruce Hardy of Kenyon College. The cord was made of three separate strands of fiber taken from the inner bark of a coniferous tree. The bark fibers would have been harvested in the spring or early summer, soaked in water, and separated into strands. “It’s not something you just sit down and do,” says Hardy. The strands were then twisted in a clockwise direction to hold the fibers together, after which they were twisted together in a counterclockwise motion to make the cord. This has led Hardy to believe that Neanderthals shared a cognitive capacity for mathematics with modern humans. Hardy thinks this cord-making technology may date back much further, but the earliest examples probably have not survived. “We are missing so much of what was there,” he says. “Something like this gives you a window into that missing world.”

More than 40,000 years ago, Neanderthals living at the site of Abri du Maras in southeastern France made what is the earliest known piece of cord. This apparently simple technology is now providing insights into the workings of the Neanderthal mind, says archaeologist Bruce Hardy of Kenyon College. The cord was made of three separate strands of fiber taken from the inner bark of a coniferous tree. The bark fibers would have been harvested in the spring or early summer, soaked in water, and separated into strands. “It’s not something you just sit down and do,” says Hardy. The strands were then twisted in a clockwise direction to hold the fibers together, after which they were twisted together in a counterclockwise motion to make the cord. This has led Hardy to believe that Neanderthals shared a cognitive capacity for mathematics with modern humans. Hardy thinks this cord-making technology may date back much further, but the earliest examples probably have not survived. “We are missing so much of what was there,” he says. “Something like this gives you a window into that missing world.”

Prized Polo...Donkeys?

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Tuesday, June 09, 2020

Remains of three small donkeys unearthed in a noblewoman’s tomb in the ancient Chinese capital of Chang’an might provide the first archaeological evidence of the game lvju, or donkey polo. According to Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618–906) historical texts, the sport was a favorite pastime of elite women and older members of the imperial court, providing a safer alternative to the dangerous, often fatal, version played on horseback. The sacrifice of these donkeys seems to have been a rare event carried out in honor of the deceased, a woman named Cui Shi who died in A.D. 878 at the age of 59. Her husband, Bao Gao, was a provincial governor whose horse polo–playing prowess earned him a promotion—and cost him an eye.

Remains of three small donkeys unearthed in a noblewoman’s tomb in the ancient Chinese capital of Chang’an might provide the first archaeological evidence of the game lvju, or donkey polo. According to Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618–906) historical texts, the sport was a favorite pastime of elite women and older members of the imperial court, providing a safer alternative to the dangerous, often fatal, version played on horseback. The sacrifice of these donkeys seems to have been a rare event carried out in honor of the deceased, a woman named Cui Shi who died in A.D. 878 at the age of 59. Her husband, Bao Gao, was a provincial governor whose horse polo–playing prowess earned him a promotion—and cost him an eye.

Biomechanical analysis of the donkey bones by a Chinese-American research team has shown that the animals experienced unusual patterns of locomotion, such as rapid acceleration and deceleration, that could be consistent with playing polo, explains anthropologist Fiona Marshall of Washington University in St. Louis. Whether or not these were Cui Shi’s actual polo donkeys, they may have been buried with her, along with a lead stirrup, to enable her to continue to play the game in the afterlife.

History in Ice

By JASON URBANUS

Tuesday, June 09, 2020

Lead pollution levels from the Middle Ages preserved in an ice core taken from Colle Gnifetti glacier in the Swiss Alps reflect political upheaval in England, some 500 miles away, a multidisciplinary research team has found. In addition to studying archaeological data and tax records, the researchers used lasers to measure how lead levels in the core changed from year to year. They observed a major spike in lead pollution during the reign of the English Angevin kings—Henry II, Richard I, and John—between 1154 and 1216, when economic growth led to an increase in silver and lead production from British mines. Lead particles from the extraction and smelting processes were carried southeast by weather patterns, and traces of the metal were trapped in Swiss glaciers.

Lead pollution levels from the Middle Ages preserved in an ice core taken from Colle Gnifetti glacier in the Swiss Alps reflect political upheaval in England, some 500 miles away, a multidisciplinary research team has found. In addition to studying archaeological data and tax records, the researchers used lasers to measure how lead levels in the core changed from year to year. They observed a major spike in lead pollution during the reign of the English Angevin kings—Henry II, Richard I, and John—between 1154 and 1216, when economic growth led to an increase in silver and lead production from British mines. Lead particles from the extraction and smelting processes were carried southeast by weather patterns, and traces of the metal were trapped in Swiss glaciers.

The researchers noticed fluctuations in annual pollution levels, which they were able to correlate with specific historical events. During wartime or when a monarch died, lead production dipped, leading to lower levels. When a new monarch was secure, there were usually major building projects that required an increase in revenue and raw materials, which, in turn, produced more pollution. Specific occurrences that appear to match changes in lead pollution levels include the death of Henry II, in 1189, Richard I’s absence during the Third Crusade, from 1190 to 1194, and the assassination of Thomas Becket, archbishop of Canterbury, in 1170. “The whole team was very surprised at the extent of demonstrable association between political events, lead production, and lead and silver pollution in the glacier,” says University of Nottingham archaeologist Christopher Loveluck. “It was one of those ‘X marks the spot’ moments that never happen.”

Roman River Cruiser

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Tuesday, June 09, 2020

Strip miners in the eastern Serbian town of Drmno uncovered a flat-bottomed ship and two monoxyles, or dugout longboats, along the banks of an ancient tributary of the Danube near the garrison at the Roman city of Viminacium. Measuring nearly 50 feet long and built for navigating shallow waters, the ship, which carried a crew of between 30 and 40, was used for either transport or combat. The timber-carved longboats were of a type used by the Avars and other nomadic groups who attacked the Romans at Viminacium. All three vessels likely date to the Roman period, explains archaeologist Miomir Korać of the Institute of Archaeology in Belgrade. “There is a possibility that the monoxyles were part of the invasion fleet that ultimately ended life as the Romans knew it at Viminacium in the early seventh century A.D.,” he says. “It looks like they were simply abandoned on the banks.”

Strip miners in the eastern Serbian town of Drmno uncovered a flat-bottomed ship and two monoxyles, or dugout longboats, along the banks of an ancient tributary of the Danube near the garrison at the Roman city of Viminacium. Measuring nearly 50 feet long and built for navigating shallow waters, the ship, which carried a crew of between 30 and 40, was used for either transport or combat. The timber-carved longboats were of a type used by the Avars and other nomadic groups who attacked the Romans at Viminacium. All three vessels likely date to the Roman period, explains archaeologist Miomir Korać of the Institute of Archaeology in Belgrade. “There is a possibility that the monoxyles were part of the invasion fleet that ultimately ended life as the Romans knew it at Viminacium in the early seventh century A.D.,” he says. “It looks like they were simply abandoned on the banks.”

Play Ball!

By JASON URBANUS

Tuesday, June 09, 2020

The discovery of a 3,400-year-old ball court in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca has led archaeologists to reconsider the origins of a popular ancient Mesoamerican sport. Although several different types of ball game were played by the Olmecs, the Maya, and the Aztecs, the best-known version was contested on a monumental stone court and involved players knocking around a rubber ball using their hips. (See “From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World: Headdresses.”) The earliest evidence for these ball courts dates to around 1650 B.C. and their prevalence at sites near the Gulf Coast and in the Pacific coastal lowlands has led scholars to believe that the game was developed in that region. However, recent excavations at the highland site of Etlatongo have uncovered two of these structures, as well as ballplayer figurines, suggesting that highland societies were playing the ball game almost as early as their lowland counterparts. One of the courts dates to between 1443 and 1305 B.C., making it 800 years older than any other playing field previously found in a highland context. “The discovery of these ball courts in Oaxaca indicates that highland groups were important players in the development of the formal ball game,” says George Washington University archaeologist Jeffrey Blomster. “The hip-ball game’s development was an important part of the establishment of Mesoamerican civilizations, and multiple regions were involved in its origin.”

The discovery of a 3,400-year-old ball court in the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca has led archaeologists to reconsider the origins of a popular ancient Mesoamerican sport. Although several different types of ball game were played by the Olmecs, the Maya, and the Aztecs, the best-known version was contested on a monumental stone court and involved players knocking around a rubber ball using their hips. (See “From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World: Headdresses.”) The earliest evidence for these ball courts dates to around 1650 B.C. and their prevalence at sites near the Gulf Coast and in the Pacific coastal lowlands has led scholars to believe that the game was developed in that region. However, recent excavations at the highland site of Etlatongo have uncovered two of these structures, as well as ballplayer figurines, suggesting that highland societies were playing the ball game almost as early as their lowland counterparts. One of the courts dates to between 1443 and 1305 B.C., making it 800 years older than any other playing field previously found in a highland context. “The discovery of these ball courts in Oaxaca indicates that highland groups were important players in the development of the formal ball game,” says George Washington University archaeologist Jeffrey Blomster. “The hip-ball game’s development was an important part of the establishment of Mesoamerican civilizations, and multiple regions were involved in its origin.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World

A Silk Road Renaissance

Idol of the Painted Temple

Letter from Normandy

Digs & Discoveries

The Emperor of Stones

Off the Grid

Ice Age Ice Box

Sticking Its Neck Out

ID'ing England's First Nun

Play Ball!

History in Ice

Roman River Cruiser

Prized Polo...Donkeys?

Twisted Neanderthal Tech

Around the World

Prehistoric Floridian fishermen, Hannibal’s army in Spain, Paleolithic mystery spheres, and a lost Maya city

Artifact

A Roman soldier’s gift to the gods

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement