Digs & Discoveries

ID'ing England's First Nun

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, June 09, 2020

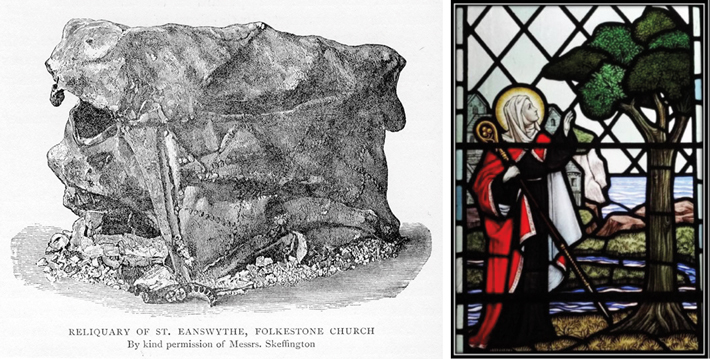

Many people in the port town of Folkestone in southeastern England still revere Saint Eanswythe, a seventh-century Anglo-Saxon princess who helped found Folkestone Priory, the first nunnery in England. Her remains were thought to have been interred at the priory until the 1530s, but went missing after Henry VIII dissolved the country’s monasteries. In 1885, a lead container with human bones was discovered concealed in a wall near the priory’s altar. It was long assumed the relics were Saint Eanswythe’s, and that they had been hidden to protect them from the Tudor king’s machinations. Now, work on the reliquary led by Canterbury Archaeological Trust archaeologist Andrew Richardson has provided new evidence that the remains are in fact those of the missing holy woman.

Many people in the port town of Folkestone in southeastern England still revere Saint Eanswythe, a seventh-century Anglo-Saxon princess who helped found Folkestone Priory, the first nunnery in England. Her remains were thought to have been interred at the priory until the 1530s, but went missing after Henry VIII dissolved the country’s monasteries. In 1885, a lead container with human bones was discovered concealed in a wall near the priory’s altar. It was long assumed the relics were Saint Eanswythe’s, and that they had been hidden to protect them from the Tudor king’s machinations. Now, work on the reliquary led by Canterbury Archaeological Trust archaeologist Andrew Richardson has provided new evidence that the remains are in fact those of the missing holy woman.

The team’s study shows that the container dates to around the eighth century, and that the remains belonged to a young woman of about 20 years old who lived in the mid-seventh century. Says Richardson, “The strong probability is that this young person, concealed in a prestigious location within a church known to have housed her remains, is indeed Eanswythe.”

Sticking Its Neck Out

By ZACH ZORICH

Tuesday, June 09, 2020

Skulls receive most of the attention in the study of human evolution, but the atlas vertebra, which sits just beneath the cranium at the top of the spinal column, can also provide valuable information about humanity’s early ancestors. Atlas vertebrae rarely survive in the fossil record, but the skeleton of “Little Foot,” a 3.67-million-year-old human ancestor belonging to the species Australopithecus prometheus, which was discovered at the site of Sterkfontein in South Africa, includes a particularly well-preserved example. An international research team recently made a micro-CT scan of Little Foot’s atlas vertebra. It revealed that the australopithecine had already evolved a humanlike head posture even though it had an ape-size brain measuring just one-third the size of a modern human brain. The scan also showed that, compared with modern humans, blood flowed through the atlas vertebra to Little Foot’s brain at a much lower rate. According to Amelie Beaudet of the University of the Witwatersrand, this indicates that australopithecines probably did not eat the calorie- and protein-rich diet that allowed larger brains to evolve.

Skulls receive most of the attention in the study of human evolution, but the atlas vertebra, which sits just beneath the cranium at the top of the spinal column, can also provide valuable information about humanity’s early ancestors. Atlas vertebrae rarely survive in the fossil record, but the skeleton of “Little Foot,” a 3.67-million-year-old human ancestor belonging to the species Australopithecus prometheus, which was discovered at the site of Sterkfontein in South Africa, includes a particularly well-preserved example. An international research team recently made a micro-CT scan of Little Foot’s atlas vertebra. It revealed that the australopithecine had already evolved a humanlike head posture even though it had an ape-size brain measuring just one-third the size of a modern human brain. The scan also showed that, compared with modern humans, blood flowed through the atlas vertebra to Little Foot’s brain at a much lower rate. According to Amelie Beaudet of the University of the Witwatersrand, this indicates that australopithecines probably did not eat the calorie- and protein-rich diet that allowed larger brains to evolve.

Off the Grid

By MARLEY BROWN

Tuesday, June 09, 2020

When some of the first British farmers to live in the Lake District needed to gather at a central location, they may have chosen Castlerigg Stone Circle, a Neolithic monument built some 5,000 years ago. The circle measures almost 100 feet in diameter and consists of 38 stones varying in height from 3.5 to 7.5 feet. Later Bronze Age stone monuments often contain burials, but no human remains have been discovered at Castlerigg. Rather than serving as a memorial to the dead, the circle likely hosted a mix of community functions. “A helpful analogy is the medieval parish church, which was a religious center, but also often the site of social gathering and the marketplace,” says archaeologist Tom Clare, emeritus of Liverpool John Moores University.

When some of the first British farmers to live in the Lake District needed to gather at a central location, they may have chosen Castlerigg Stone Circle, a Neolithic monument built some 5,000 years ago. The circle measures almost 100 feet in diameter and consists of 38 stones varying in height from 3.5 to 7.5 feet. Later Bronze Age stone monuments often contain burials, but no human remains have been discovered at Castlerigg. Rather than serving as a memorial to the dead, the circle likely hosted a mix of community functions. “A helpful analogy is the medieval parish church, which was a religious center, but also often the site of social gathering and the marketplace,” says archaeologist Tom Clare, emeritus of Liverpool John Moores University.

At the time Castlerigg was built, much of northern Europe was heavily forested, and the Lake District’s valley bottoms were often filled with standing water or dense swampland. “Castlerigg’s position on a low ridgeline at the center of three valleys would have placed it along a traversable pathway for farmers moving livestock from higher pastures in summer months down to lower elevations for the winter,” explains ecologist David Wilkinson of the University of Lincoln. Some of the stones at Castlerigg that were lying on their side when antiquarians such as William Stukeley observed the site in the eighteenth century have since been put upright. Clare cautions that making exact determinations about the cosmological or spiritual meaning of the monument to those who built it may never be possible. Still, the task of raising the stones of Castlerigg would have required a level of effort in proportion to its profound importance to the community. “One generation might have added to what the previous generation did,” Clare says. “Part of the process of being involved in this society was that you contributed labor, you helped contribute to these communal structures.”

THE SITE

The stone circle is most easily accessible by car and the route is well marked from the neighboring town of Keswick. Visitors can park along the road approaching the circle—be prepared to walk uphill. On reaching the field, look for a wide gap in the circle flanked by two tall stones. This may have been the entrance to the monument and is a feature also found in earlier Neolithic timber structures. This similarity has led some researchers to suggest Castlerigg may be a particularly early example of a Neolithic stone circle.

WHILE YOU’RE THERE

WHILE YOU’RE THERE

The Lake District may be as well known for its literary heritage as it is for its physical majesty, and many of the so-called Lake Poets were inspired by Castlerigg. After leaving the site, take a 15-minute drive south to the village of Grasmere to visit the Wordsworth Trust. Then continue south another 11 miles to tour Beatrix Potter’s Hill Top farmhouse.

Ice Age Ice Box

By MARLEY BROWN

Tuesday, June 09, 2020

When a circular structure measuring more than 40 feet in diameter, made entirely from mammoth bones, was discovered in western Russia in 2014, its purpose was unclear. Now, researchers have investigated debris from the site of Kostenki, which is located along the Don River just south of the Russian city of Voronezh and was inhabited by hunter-gatherers some 25,000 years ago. By separating possible evidence of human habitation, such as charcoal produced by fires, from sediment, they determined that the structure was likely not used for shelter. “The density of this debris was far less than we’d expect to see if it was an intensively occupied dwelling,” says archaeologist Alexander Pryor of the University of Exeter. It would have been difficult to build a roof on such a large structure, he adds. Furthermore, many of the bones used to build it appear to have had fat and cartilage still attached to them, which would have created a smelly, unhygienic environment. Instead, Pryor suggests, the structure may have been used to store food, possibly allowing the community to eat well while remaining at the site for weeks or even months at a time.

When a circular structure measuring more than 40 feet in diameter, made entirely from mammoth bones, was discovered in western Russia in 2014, its purpose was unclear. Now, researchers have investigated debris from the site of Kostenki, which is located along the Don River just south of the Russian city of Voronezh and was inhabited by hunter-gatherers some 25,000 years ago. By separating possible evidence of human habitation, such as charcoal produced by fires, from sediment, they determined that the structure was likely not used for shelter. “The density of this debris was far less than we’d expect to see if it was an intensively occupied dwelling,” says archaeologist Alexander Pryor of the University of Exeter. It would have been difficult to build a roof on such a large structure, he adds. Furthermore, many of the bones used to build it appear to have had fat and cartilage still attached to them, which would have created a smelly, unhygienic environment. Instead, Pryor suggests, the structure may have been used to store food, possibly allowing the community to eat well while remaining at the site for weeks or even months at a time.

The Emperor of Stones

By DANIEL WEISS

Tuesday, June 09, 2020

In the language of the Vikings, Old Norse, rök means “monolith,” and no other runestone stands out from its peers in more ways than Sweden’s Rök. The five-ton stone measures eight feet tall and its five sides are covered with the longest runic inscription in existence—some 760 runes divided into 28 lines. And, while the vast majority of runestones date to after the mid-tenth century A.D., the Rök was inscribed much earlier, around A.D. 800. “It’s the emperor of runestones,” says Henrik Williams, a runologist at Uppsala University. “Nothing can compare with it.”

In the language of the Vikings, Old Norse, rök means “monolith,” and no other runestone stands out from its peers in more ways than Sweden’s Rök. The five-ton stone measures eight feet tall and its five sides are covered with the longest runic inscription in existence—some 760 runes divided into 28 lines. And, while the vast majority of runestones date to after the mid-tenth century A.D., the Rök was inscribed much earlier, around A.D. 800. “It’s the emperor of runestones,” says Henrik Williams, a runologist at Uppsala University. “Nothing can compare with it.”

Although scholars are united in recognizing the Rök’s singularity, with regard to its meaning all they can agree on is that it was set up by a local chieftain named Varinn as a memorial to his son Vamoth. The stone’s inscription has defied attempts at interpretation since the mid-nineteenth century, when it was transcribed after the Rök was removed from a structure into which it had been built centuries earlier. Decoding the inscription is made especially difficult as it features several styles of writing, including the earliest form of runes, called Elder Futhark, and two types of cipher. It’s not clear in what order the sections of the text are supposed to be read—or if it was even intended to be understood by mortals at all. “I don’t think this was ever meant to be read by humans,” says Bo Gräslund, an archaeologist at Uppsala University. “It was only meant for the gods.”

Now, a team composed of Williams, Gräslund, University of Gothenburg linguist Per Holmberg, and Stockholm University historian of religion Olof Sundqvist has developed a new interpretation of the inscription that ties it to themes in Norse mythology and to a devastating sixth-century climate crisis. The very beginning of the inscription—scholars generally agree it is the beginning—describes Vamoth as “death-doomed.” While most runestones memorialize the dead, says Williams, this phrase is unique to the Rök and suggests that the young man was fated to die for a particular reason.

Based on a number of allusions strewn throughout the inscription, the researchers believe that Vamoth perished so he could join the army of the chief Norse god, Odin, in Ragnarok, the apocalyptic battle pitting the Viking gods against their enemies, the giants. In one section, the researchers have detected a reference to one of the chief giants, the monstrous wolf Fenrir, swallowing the sun, the act that sets Ragnarok in motion. Another section describes Fenrir facing off against 20 kings—members of Odin’s army—on the Grove of Sparks, a name for the Ragnarok battlefield. And, near the end of the inscription, the team has gleaned a reference to Odin’s son Vitharr, who vanquishes Fenrir after the creature kills his father. Only then can the sun’s daughter take her mother’s place in the sky.

For the team, another key to the inscription’s meaning is found in a line that mentions someone “who nine generations ago lost their life.” Given that the runestone dates to around A.D. 800, and allowing 30 years per generation, this event would have occurred in the early sixth century. The scholars believe the line describes the death of the sun and refers to a period beginning in A.D. 536 when a series of volcanic eruptions is known to have blocked sunlight for several years, leading to mass starvation.

This reference to events of nearly three centuries earlier, the researchers suggest, was likely prompted by a number of happenings reminiscent of those harrowing times. “We know that there were solar storms that turned the sky red and would have caused very cold summers,” Williams says. “And there was a near-total solar eclipse that would have scared the hell out of people.” With the threat of a crisis looming, Vamoth is described on the runestone as having been cut down before his time in order to help Odin’s army defeat the giants, ensuring that the sun would continue to shine.

To watch a video of Henrik Williams reading the Rök runestone’s inscription, click below.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

From Head to Toe in the Ancient Maya World

A Silk Road Renaissance

Idol of the Painted Temple

Letter from Normandy

Digs & Discoveries

The Emperor of Stones

Off the Grid

Ice Age Ice Box

Sticking Its Neck Out

ID'ing England's First Nun

Play Ball!

History in Ice

Roman River Cruiser

Prized Polo...Donkeys?

Twisted Neanderthal Tech

Around the World

Prehistoric Floridian fishermen, Hannibal’s army in Spain, Paleolithic mystery spheres, and a lost Maya city

Artifact

A Roman soldier’s gift to the gods

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement