Features

Walking Into New Worlds

By KAREN COATES

Tuesday, September 29, 2020

Ancient canyons, dry mesas, and high deserts form the iconic landscape of what is now called the American Southwest. To the Navajo, who call themselves Diné (“the people”), this is sacred land, a place they know as Dinétah. It’s the center of their universe, the place where Diné history began. The story of their emergence is passed from generation to generation through days of oral accounts that describe how their ancestors traveled through four worlds—black, blue, yellow, and white—moving through each at an appropriate time, aided by sacred creatures, usually animals or insects, to arrive at the present world. “I think this is a metaphor for the stages of development of our human consciousness and human spirit,” says Navajo archaeologist Adesbah Foguth. Foguth works as an interpretive ranger at Chaco Culture National Historical Park just to the east of the Navajo reservation in the Four Corners region of New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and Utah. When she gives tours of the park, she shares Native histories and talks about the Navajo connection to this land. “We evolved here, we became distinctly Navajo people here,” she says. Her understanding of Navajo emergence also includes a sense of movement and change. “We were also literally migrating on the landscape, moving from place to place.”

Ancient canyons, dry mesas, and high deserts form the iconic landscape of what is now called the American Southwest. To the Navajo, who call themselves Diné (“the people”), this is sacred land, a place they know as Dinétah. It’s the center of their universe, the place where Diné history began. The story of their emergence is passed from generation to generation through days of oral accounts that describe how their ancestors traveled through four worlds—black, blue, yellow, and white—moving through each at an appropriate time, aided by sacred creatures, usually animals or insects, to arrive at the present world. “I think this is a metaphor for the stages of development of our human consciousness and human spirit,” says Navajo archaeologist Adesbah Foguth. Foguth works as an interpretive ranger at Chaco Culture National Historical Park just to the east of the Navajo reservation in the Four Corners region of New Mexico, Colorado, Arizona, and Utah. When she gives tours of the park, she shares Native histories and talks about the Navajo connection to this land. “We evolved here, we became distinctly Navajo people here,” she says. Her understanding of Navajo emergence also includes a sense of movement and change. “We were also literally migrating on the landscape, moving from place to place.”

Navajo is part of the largest indigenous language family in North America, known as Dene, which includes more than 50 languages spoken by Native peoples in the Canadian Subarctic, the Pacific Northwest, and the American Southwest, where the Navajo and their distant cousins, the Apache, are among its southernmost speakers. Currently, archaeologists are attempting to trace the epic 1,500-mile-plus journey the ancestors of the Navajo and Apache made across North America’s mountains and plains. This was one of the most consequential population movements in North American history, taking people from the Canadian Subarctic, among the wettest landscapes in North America, to the desert Southwest, its most arid region. At the beginning of the migration, the ancestors of today’s Navajo and Apache were foragers. Centuries later, many of their descendants had become farmers. This massive migration forever changed the cultural landscape of the Southwest.

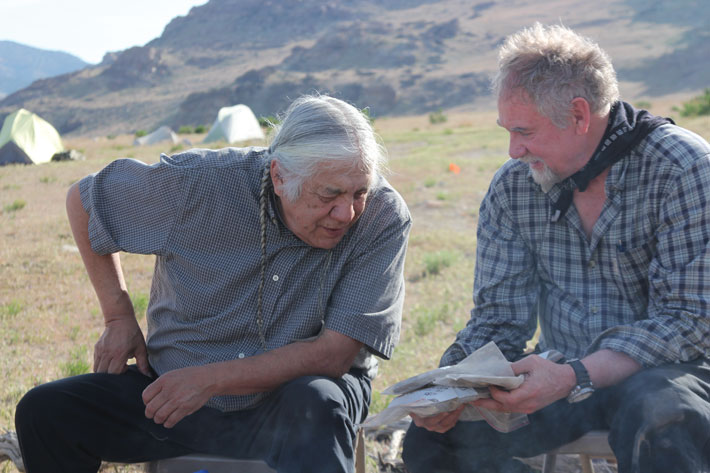

One effort to comprehend this great migration is the Apachean Origins Project, headed by University of Alberta archaeologist Jack Ives and Brigham Young University archaeologist Joel Janetski. “Apachean” refers to a subgroup of Dene speakers comprising the Apache and Navajo. Ives and Janetski lead a team of researchers using archaeological, linguistic, isotopic, and paleoenvironmental evidence to study the links among distant Dene speakers. They also work closely with Dene elders to understand not just when the migration happened, but how the migrators interacted with people they encountered. “Migration creates an infinite number of scenarios for contact with new people,” Ives says. Those interactions can lead to intermarriage, shared cultural traits, and a coalescence of what previously were two or more distinct peoples.

One effort to comprehend this great migration is the Apachean Origins Project, headed by University of Alberta archaeologist Jack Ives and Brigham Young University archaeologist Joel Janetski. “Apachean” refers to a subgroup of Dene speakers comprising the Apache and Navajo. Ives and Janetski lead a team of researchers using archaeological, linguistic, isotopic, and paleoenvironmental evidence to study the links among distant Dene speakers. They also work closely with Dene elders to understand not just when the migration happened, but how the migrators interacted with people they encountered. “Migration creates an infinite number of scenarios for contact with new people,” Ives says. Those interactions can lead to intermarriage, shared cultural traits, and a coalescence of what previously were two or more distinct peoples.

Ives and Janetski have focused their work on a remarkable site, which, nearly a century ago, provided surprising evidence that a culture accustomed to life more than 1,000 miles north in the Subarctic also lived in the American West. How they got there and what happened along the way are a sometimes misunderstood, uniquely North American migration story.

A Nubian Kingdom Rises

By MATT STIRN

Monday, August 10, 2020

As the Nile slices through the barren desert of North Africa, it runs straight north, with the exception of one magnificent curve, reminiscent of a giant S. This stretch of the river winds through northern Sudan approximately 250 miles south of the Egyptian border. Known as the Great Bend of the Nile, it marks the southern boundary of Nubia, a region that stretches from Sudan into southern Egypt and has been home to the Nubian people for millennia.

As the Nile slices through the barren desert of North Africa, it runs straight north, with the exception of one magnificent curve, reminiscent of a giant S. This stretch of the river winds through northern Sudan approximately 250 miles south of the Egyptian border. Known as the Great Bend of the Nile, it marks the southern boundary of Nubia, a region that stretches from Sudan into southern Egypt and has been home to the Nubian people for millennia.

The modern Nubian town of Kerma sits at the northern end of the Great Bend. It is a bustling riverside community teeming with animated produce markets and fishing boats piled high with six-foot Nile carp. At the center of the town rises a five-story mudbrick tower, or deffufa in the Nubian language, which has kept watch there for more than 4,000 years. Consisting of multiple levels, an interior staircase leading to a rooftop platform, and a series of subterranean chambers, the Deffufa once functioned as a temple and the religious center of a Nubian city that was founded there around 2500 B.C. on what was once an island in the middle of the Nile. Also known as Kerma, it was the earliest urban center in Africa outside Egypt.

The modern Nubian town of Kerma sits at the northern end of the Great Bend. It is a bustling riverside community teeming with animated produce markets and fishing boats piled high with six-foot Nile carp. At the center of the town rises a five-story mudbrick tower, or deffufa in the Nubian language, which has kept watch there for more than 4,000 years. Consisting of multiple levels, an interior staircase leading to a rooftop platform, and a series of subterranean chambers, the Deffufa once functioned as a temple and the religious center of a Nubian city that was founded there around 2500 B.C. on what was once an island in the middle of the Nile. Also known as Kerma, it was the earliest urban center in Africa outside Egypt.

Below the Deffufa, archaeologist Charles Bonnet of the University of Geneva has spent five decades excavating Kerma and its necropolis. Much of what scholars know of early Nubian history comes from ancient Egyptian sources, and, for a time, some believed Kerma was simply an Egyptian colonial outpost. The pharaoh Thutmose I (r. ca. 1504–1492 B.C.) did indeed invade Nubia, and his successors ruled there for centuries, just as later Nubian kings invaded and held Egypt during the 25th Dynasty (ca. 712–664 B.C.). The ancient history of Egyptians and Nubians is, thus, closely intertwined. But Bonnet’s excavations are offering a markedly Nubian perspective on the earliest days of Kerma and its role as the capital of a far-reaching kingdom that dominated the Nile south of Egypt. His finds there and at a neighboring ancient settlement known as Dukki Gel suggest that this urban center was an ethnic melting pot, with origins tied to a complex web of cultures native to both the Sahara, and, farther south, parts of central Africa. These discoveries have gradually revealed the complex nature of a powerful African kingdom.

Bonnet began working at Kerma in 1976, some 50 years after Egyptologist George Reisner, the first archaeologist to dig at the site, closed his excavations. As the leader of the joint Harvard University–Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition, Reisner had spent many years directing excavations at the Great Pyramid of Giza and working in southern Egypt, where he developed an interest in ancient Nubian culture and in connecting its history to that of the Egyptians. “Reisner thought the place to find new Egyptian art would be in northern Sudan,” says Larry Berman, curator of Egyptology at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. In 1913, by request of the Sudanese Antiquity Center in Khartoum, Reisner was directed to Kerma, which, at the time, was only vaguely known to Westerners from the accounts of nineteenth-century European explorers. He was completely unprepared for what was to come. “When Reisner arrived at Kerma, he accidentally discovered a civilization the scope of which was unknown to the Western world,” says Berman.

|

Slideshow:

|

New Look at Ancient Nubia

|

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Digs & Discoveries

Siberian Island Enigma

Off the Grid

Closing in on a Pharaoh's Tomb

A Rare Egg

Mouse in the House

Commander's Orders

The Means of Production

Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

Missing Mosaics

Stonehenge's New Neighbor

Dark Earth in the Amazon

Reindeer Training

Around the World

A president’s torpedo boat, Cahokia corn farmers, a Viking surprise, and Genghis Khan in winter

Artifact

Reeling in the years

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

In 1930, a young University of Utah archaeologist named Julian Steward began excavating in two caves on Promontory Point, a peninsula on the northern edge of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. The caves’ dry environment proved ideal for preserving artifacts, and over two years, Steward found baskets, pottery, fiber ropes and mats, juniper bark, bison bones, arrow points and shafts, bow fragments, knife handles, scrapers, and awls. He also found the remnants of some 250 moccasins that strongly resembled footwear made and worn by Canadian Dene cultures past and present. Each of the carefully stitched intact moccasins, which are now stored at the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU), reflects the size and gait of the person who wore it. Some are tiny, made for children. Some have blown-out heels that were later repaired. A few have decorative porcupine quills, and all have small stitches and puckering around the toes. And, 700 years after the Promontory people wore them, these moccasins still smell strongly of smoke—a reminder of the fires used to tan their hides. The moccasins Steward found are unlike those made by the neighboring people who belonged to a farming culture known today as the Fremont. Although the Fremont created elaborate rock art and clay figurines, their moccasins don’t have the distinctive puckered stitching and quillwork of those found in the caves.

In 1930, a young University of Utah archaeologist named Julian Steward began excavating in two caves on Promontory Point, a peninsula on the northern edge of Utah’s Great Salt Lake. The caves’ dry environment proved ideal for preserving artifacts, and over two years, Steward found baskets, pottery, fiber ropes and mats, juniper bark, bison bones, arrow points and shafts, bow fragments, knife handles, scrapers, and awls. He also found the remnants of some 250 moccasins that strongly resembled footwear made and worn by Canadian Dene cultures past and present. Each of the carefully stitched intact moccasins, which are now stored at the Natural History Museum of Utah (NHMU), reflects the size and gait of the person who wore it. Some are tiny, made for children. Some have blown-out heels that were later repaired. A few have decorative porcupine quills, and all have small stitches and puckering around the toes. And, 700 years after the Promontory people wore them, these moccasins still smell strongly of smoke—a reminder of the fires used to tan their hides. The moccasins Steward found are unlike those made by the neighboring people who belonged to a farming culture known today as the Fremont. Although the Fremont created elaborate rock art and clay figurines, their moccasins don’t have the distinctive puckered stitching and quillwork of those found in the caves. One of their first efforts was to radiocarbon date Steward’s moccasins. They found that the dates centered around A.D. 1250 to 1290. This exceptionally narrow time frame suggests that perhaps just a few generations of Apachean ancestors lived in the cave some 400 years before the Spanish colonial period to which some archaeologists had linked early Apacheans. The thirteenth century was a time of extreme drought in North America. The archaeological record shows that the Fremont in the area around Promontory Caves abandoned farming during this time, and, out of desperation, turned to foraging. But the people living in the caves seem to have thrived as bison hunters. “This was a healthy, vibrant population that was doing really well,” says Ives. When Ives and his team conducted their own excavations at Promontory Caves between 2011 and 2014, they uncovered still more moccasins. By studying the sizes of all the moccasins excavated, they concluded that some 80 percent of them belonged to children or teenagers, suggesting that the mid-thirteenth century population of Promontory Caves was young and rapidly increasing.

One of their first efforts was to radiocarbon date Steward’s moccasins. They found that the dates centered around A.D. 1250 to 1290. This exceptionally narrow time frame suggests that perhaps just a few generations of Apachean ancestors lived in the cave some 400 years before the Spanish colonial period to which some archaeologists had linked early Apacheans. The thirteenth century was a time of extreme drought in North America. The archaeological record shows that the Fremont in the area around Promontory Caves abandoned farming during this time, and, out of desperation, turned to foraging. But the people living in the caves seem to have thrived as bison hunters. “This was a healthy, vibrant population that was doing really well,” says Ives. When Ives and his team conducted their own excavations at Promontory Caves between 2011 and 2014, they uncovered still more moccasins. By studying the sizes of all the moccasins excavated, they concluded that some 80 percent of them belonged to children or teenagers, suggesting that the mid-thirteenth century population of Promontory Caves was young and rapidly increasing. Working with Native elders, the team was able to confirm that the style of the moccasins both Steward and they had unearthed was distinctly Dene. One of these elders is Bruce Starlight of the Tsuut’ina Nation, a Dene people who live on the plains of modern-day Alberta. “I never talk about something I don’t know,” says Starlight. He has examined the Promontory Caves moccasins and believes they prove Dene people once lived at the site. “The Dene still have that style of moccasin,” he says. The footwear could even have been used as a form of identification. “A long time ago, when they did battle among each other, the first thing they looked at was your moccasins,” says Starlight. Unlike the simpler Fremont moccasins, those found in Promontory Caves would have required a lot of time and a high degree of skill to make. Ives speculates that the moccasins might not only have been an expression of culture, but of care for the makers’ loved ones. “The moccasins are highly evocative,” says Ives. “We all react to them on a human level; you can sense a person.” Many of them still have distinct indentations of toes, the individual marks of the people who wore them as they walked across the landscape.

Working with Native elders, the team was able to confirm that the style of the moccasins both Steward and they had unearthed was distinctly Dene. One of these elders is Bruce Starlight of the Tsuut’ina Nation, a Dene people who live on the plains of modern-day Alberta. “I never talk about something I don’t know,” says Starlight. He has examined the Promontory Caves moccasins and believes they prove Dene people once lived at the site. “The Dene still have that style of moccasin,” he says. The footwear could even have been used as a form of identification. “A long time ago, when they did battle among each other, the first thing they looked at was your moccasins,” says Starlight. Unlike the simpler Fremont moccasins, those found in Promontory Caves would have required a lot of time and a high degree of skill to make. Ives speculates that the moccasins might not only have been an expression of culture, but of care for the makers’ loved ones. “The moccasins are highly evocative,” says Ives. “We all react to them on a human level; you can sense a person.” Many of them still have distinct indentations of toes, the individual marks of the people who wore them as they walked across the landscape. The gambling items from Promontory Caves include a juniper-bark ball, decorated sticks, badminton-style birdies, hoops, and darts. But the most common artifacts are dice made of cane, which, Yanicki says, were typically used by women. While Native dice games varied across the continent, they usually involved tossing two-sided objects in a basket or bowl or striking them against a hard surface. Gamblers could earn points depending on whether the dice landed face up or face down. Gaming would have led to other social interactions, from meetings and feasts to alliances and intermarriages. “That’s how new societies ultimately form, as groups spend more time together and forge mutual futures,” Yanicki says, adding that this results in the emergence of new social identities.

The gambling items from Promontory Caves include a juniper-bark ball, decorated sticks, badminton-style birdies, hoops, and darts. But the most common artifacts are dice made of cane, which, Yanicki says, were typically used by women. While Native dice games varied across the continent, they usually involved tossing two-sided objects in a basket or bowl or striking them against a hard surface. Gamblers could earn points depending on whether the dice landed face up or face down. Gaming would have led to other social interactions, from meetings and feasts to alliances and intermarriages. “That’s how new societies ultimately form, as groups spend more time together and forge mutual futures,” Yanicki says, adding that this results in the emergence of new social identities. If the eruption of Mount Churchill severely disrupted the lives of Dene ancestors, that could help explain why members of the Dene language family are spread across more than 1.5 million square miles. “That’s a huge language family,” says University of Alberta linguist Sally Rice, who works with Ives. She has spent decades compiling a list of 25,000 Dene words including terms for objects, flora and fauna, and things that would have been novelties to populations moving south. For example, northern Dene people have no word for cactus, and Dene speakers in the Southwest refer to cacti using a term that essentially translates as “rose thorn.” Unlike cacti, roses are widely found in the north. “Language itself is a kind of archaeological record,” says Rice. Another example is the overlap in words for “spoon,” “horn,” and “gourd.” In northern Dene cultures, people used horns as spoons or scoops; in the south, people used gourds. The words used to describe these items are all related. At Promontory Caves, Steward unearthed examples of bison-horn spoons.

If the eruption of Mount Churchill severely disrupted the lives of Dene ancestors, that could help explain why members of the Dene language family are spread across more than 1.5 million square miles. “That’s a huge language family,” says University of Alberta linguist Sally Rice, who works with Ives. She has spent decades compiling a list of 25,000 Dene words including terms for objects, flora and fauna, and things that would have been novelties to populations moving south. For example, northern Dene people have no word for cactus, and Dene speakers in the Southwest refer to cacti using a term that essentially translates as “rose thorn.” Unlike cacti, roses are widely found in the north. “Language itself is a kind of archaeological record,” says Rice. Another example is the overlap in words for “spoon,” “horn,” and “gourd.” In northern Dene cultures, people used horns as spoons or scoops; in the south, people used gourds. The words used to describe these items are all related. At Promontory Caves, Steward unearthed examples of bison-horn spoons. Tiller is gratified to hear that the Apachean Origins Project has made great efforts to include and accurately portray Native perspectives, something that scholars haven’t always done. She cites the work of early anthropologists who visited her reservation, interviewed elders, and published the first written accounts of Jicarilla history. But the researchers missed the meaning of many of the stories, she says, because they weren’t fluent in the language, didn’t grasp the cultural context, and relied on Native translators who likely had a grade-school-level command of English. “That becomes the body of literature that’s supposed to illustrate who we are as a people,” says Tiller. She and her relatives are now retranslating the texts, which they hope to publish soon.

Tiller is gratified to hear that the Apachean Origins Project has made great efforts to include and accurately portray Native perspectives, something that scholars haven’t always done. She cites the work of early anthropologists who visited her reservation, interviewed elders, and published the first written accounts of Jicarilla history. But the researchers missed the meaning of many of the stories, she says, because they weren’t fluent in the language, didn’t grasp the cultural context, and relied on Native translators who likely had a grade-school-level command of English. “That becomes the body of literature that’s supposed to illustrate who we are as a people,” says Tiller. She and her relatives are now retranslating the texts, which they hope to publish soon. There is, in fact, growing archaeological evidence for ancestral Apachean groups moving into the greater Southwest as early as the 1300s. Archaeologist Deni Seymour has investigated several sites in southern Arizona and New Mexico that were used to store food, pottery, baskets, and other goods for later use among mobile groups. They were Dene-speaking peoples related to Apache and Navajo groups today. “Promontory Caves was just one of the stopping points along the way,” says Seymour.

There is, in fact, growing archaeological evidence for ancestral Apachean groups moving into the greater Southwest as early as the 1300s. Archaeologist Deni Seymour has investigated several sites in southern Arizona and New Mexico that were used to store food, pottery, baskets, and other goods for later use among mobile groups. They were Dene-speaking peoples related to Apache and Navajo groups today. “Promontory Caves was just one of the stopping points along the way,” says Seymour. In his early years at the site, Reisner focused on excavating the giant Deffufa and investigating tombs in the city’s necropolis two miles to the east. Dozens of royal tombs he uncovered there date to between 1750 and 1500 B.C., when the city was at its height. These tombs contained hundreds of human and animal sacrifices, jewelry crafted from quartz, amethyst, and gold, and preserved wooden funerary beds inlaid with scenes of African wildlife fashioned of ivory and mica. In one of the tombs Reisner unearthed a large, elegant granite statue depicting Lady Sennuwy, the wife of the prominent Egyptian governor Djefaihapi, who ruled a district north of Luxor sometime between 1971 and 1926 B.C. Nearby, Reisner found a broken bust of Djefaihapi himself.

In his early years at the site, Reisner focused on excavating the giant Deffufa and investigating tombs in the city’s necropolis two miles to the east. Dozens of royal tombs he uncovered there date to between 1750 and 1500 B.C., when the city was at its height. These tombs contained hundreds of human and animal sacrifices, jewelry crafted from quartz, amethyst, and gold, and preserved wooden funerary beds inlaid with scenes of African wildlife fashioned of ivory and mica. In one of the tombs Reisner unearthed a large, elegant granite statue depicting Lady Sennuwy, the wife of the prominent Egyptian governor Djefaihapi, who ruled a district north of Luxor sometime between 1971 and 1926 B.C. Nearby, Reisner found a broken bust of Djefaihapi himself. Bonnet’s work at Kerma quickly showed that Reisner was wrong. His team’s surveys of the city’s necropolis revealed 30,000 burials in addition to those Reisner had excavated, making it one of the largest cemeteries yet discovered in the ancient world. And after unearthing tombs, buildings, and pottery that predated the 1500 B.C. Egyptian invasion of Nubia, Bonnet realized that Kerma was not merely an Egyptian colony, but had been built and ruled by Nubians. “The country was wrongly believed to have only depended on Egypt,” says Bonnet. “I wanted to reconstruct a more accurate history of Sudan.” In addition to determining that Nubians had founded the city, the team began to identify evidence of other African cultures at Kerma. They discovered round huts, oval temples, and intricate curved-wall bastions that were distinct from both Egyptian and Nubian architecture, and instead mirrored buildings archaeologists have unearthed in southern Sudan and regions in central Africa. “We realized that the tombs, palaces, and temples stood out from Egyptian remains, and that a different tradition characterized the discoveries,” says Bonnet. “We were in another world.”

Bonnet’s work at Kerma quickly showed that Reisner was wrong. His team’s surveys of the city’s necropolis revealed 30,000 burials in addition to those Reisner had excavated, making it one of the largest cemeteries yet discovered in the ancient world. And after unearthing tombs, buildings, and pottery that predated the 1500 B.C. Egyptian invasion of Nubia, Bonnet realized that Kerma was not merely an Egyptian colony, but had been built and ruled by Nubians. “The country was wrongly believed to have only depended on Egypt,” says Bonnet. “I wanted to reconstruct a more accurate history of Sudan.” In addition to determining that Nubians had founded the city, the team began to identify evidence of other African cultures at Kerma. They discovered round huts, oval temples, and intricate curved-wall bastions that were distinct from both Egyptian and Nubian architecture, and instead mirrored buildings archaeologists have unearthed in southern Sudan and regions in central Africa. “We realized that the tombs, palaces, and temples stood out from Egyptian remains, and that a different tradition characterized the discoveries,” says Bonnet. “We were in another world.” The Swiss team, now under the direction of University of Neuchatel archaeologist Matthieu Honegger, gradually started to piece together the history of that previously unknown world. They found that beginning around 3100 B.C., driven in part by an increasingly arid climate, people began to settle on the island in the Nile where Kerma would rise. These new arrivals lived in small settlements and used red brushed ceramics of a type that their descendants at Kerma would also use, and placed their huts in a distinctive semicircular pattern.

The Swiss team, now under the direction of University of Neuchatel archaeologist Matthieu Honegger, gradually started to piece together the history of that previously unknown world. They found that beginning around 3100 B.C., driven in part by an increasingly arid climate, people began to settle on the island in the Nile where Kerma would rise. These new arrivals lived in small settlements and used red brushed ceramics of a type that their descendants at Kerma would also use, and placed their huts in a distinctive semicircular pattern.

Some of the best evidence that Nubians and the people of the C-Group coexisted at Kerma has been uncovered by Honegger’s team in the necropolis. They found that graves of Kerma people from this early period were generally small pit burials in which the dead were placed in a fetal position on a mat made from either leather or woven plants. Small rows of cattle skulls were often placed in an arc outside the grave, and additional objects such as ceramic vessels, jewelry, and sacrificed animals were arranged around the body. Most men were buried with an ostrich-plume bow, and most women had a wooden staff in their graves.

Some of the best evidence that Nubians and the people of the C-Group coexisted at Kerma has been uncovered by Honegger’s team in the necropolis. They found that graves of Kerma people from this early period were generally small pit burials in which the dead were placed in a fetal position on a mat made from either leather or woven plants. Small rows of cattle skulls were often placed in an arc outside the grave, and additional objects such as ceramic vessels, jewelry, and sacrificed animals were arranged around the body. Most men were buried with an ostrich-plume bow, and most women had a wooden staff in their graves.

Kerma continued to thrive after the departure of the C-Group people. Bonnet and Honegger’s excavations in the necropolis show that around 2000 B.C., Kerma’s kings initiated construction of elaborate royal tombs surrounded by thousands of cattle skulls. This signaled the beginning of a new phase in the city’s history as it grew in size and its rulers began to exert their influence across northeast Africa. Bonnet’s analysis of the multiple building stages of the Deffufa shows that it was enlarged from a chapel into a multistory temple and became the city’s religious center. Cults devoted to the sun likely worshipped atop the Deffufa and those dedicated to the underworld practiced rituals in a nearby windowless chapel. Excavations throughout the city show that the number of bakeries, workshops, religious structures, courtyards, and houses increased dramatically at this time. Bonnet also discovered that there was a significant increase in the number of wealthy houses, and that the royal quarters were expanded. The construction of increasingly robust fortifications suggests there were frequent military clashes with Egypt as both powers competed for control of the Nile Valley.

Kerma continued to thrive after the departure of the C-Group people. Bonnet and Honegger’s excavations in the necropolis show that around 2000 B.C., Kerma’s kings initiated construction of elaborate royal tombs surrounded by thousands of cattle skulls. This signaled the beginning of a new phase in the city’s history as it grew in size and its rulers began to exert their influence across northeast Africa. Bonnet’s analysis of the multiple building stages of the Deffufa shows that it was enlarged from a chapel into a multistory temple and became the city’s religious center. Cults devoted to the sun likely worshipped atop the Deffufa and those dedicated to the underworld practiced rituals in a nearby windowless chapel. Excavations throughout the city show that the number of bakeries, workshops, religious structures, courtyards, and houses increased dramatically at this time. Bonnet also discovered that there was a significant increase in the number of wealthy houses, and that the royal quarters were expanded. The construction of increasingly robust fortifications suggests there were frequent military clashes with Egypt as both powers competed for control of the Nile Valley.

Kerma was only the first capital of what would become the Kingdom of Kush, a Nubian power that reigned across northeast Africa for another 1,300 years. The Kushite kings ruled from the cities of Napata and Meroe farther south. In 2003, while excavating a New Kingdom temple complex near Dukki Gel, Bonnet’s team uncovered a cache of granite statues nearby depicting prominent Kushite kings, such as the great pharaoh Taharqa, (r. ca. 690–664 B.C.) who ruled over Egypt, and one of his successors, King Anlamani (r. ca. 623–593 B.C.). Even though the cache postdates the abandonment of Kerma by 800 years, it is clear evidence that Kushite kings continued to honor the area as the royal site where their ancestors had laid the groundwork for the rise of the Nubian Kingdom.

Kerma was only the first capital of what would become the Kingdom of Kush, a Nubian power that reigned across northeast Africa for another 1,300 years. The Kushite kings ruled from the cities of Napata and Meroe farther south. In 2003, while excavating a New Kingdom temple complex near Dukki Gel, Bonnet’s team uncovered a cache of granite statues nearby depicting prominent Kushite kings, such as the great pharaoh Taharqa, (r. ca. 690–664 B.C.) who ruled over Egypt, and one of his successors, King Anlamani (r. ca. 623–593 B.C.). Even though the cache postdates the abandonment of Kerma by 800 years, it is clear evidence that Kushite kings continued to honor the area as the royal site where their ancestors had laid the groundwork for the rise of the Nubian Kingdom.