Alcohol

Spirits for the Dead

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Friday, October 09, 2020

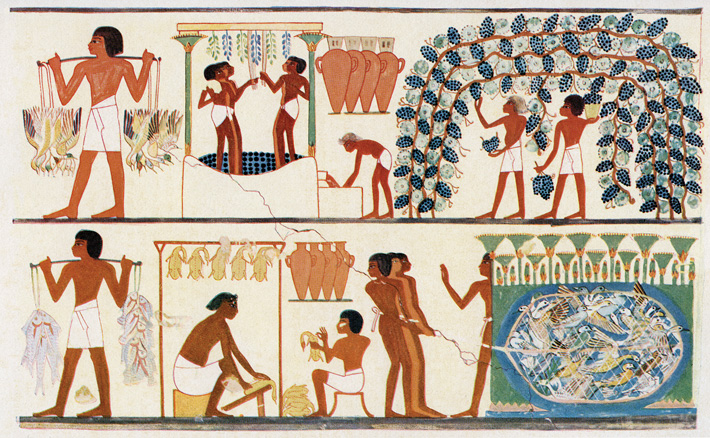

As early as the Predynastic period, beginning in the mid-fifth millennium B.C., the Egyptians placed wine jars in tombs as offerings to the dead. References to wine dating to the 1st and 2nd Dynasties have been identified on ceramic jar seals found in the burial grounds at Abydos and Saqqara, and the word for wine, “irp,” appears on 2nd Dynasty stelas. By the 4th Dynasty, in the mid-third millennium B.C., tomb designers had begun to illustrate viticulture and winemaking on tomb walls. For archaeologist Sofia Fonseca of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, such imagery offers valuable insights into the vintner’s entire process. “We have this idea that viticulture and winemaking originated in the ancient Near East, and that European wine culture is a legacy from Greece and Rome,” she says. “But the truth is that, starting more than 4,500 years ago, and for the next two millennia of Egyptian history, we have images that show a traditional process similar to those winemakers in Mediterranean regions are still using. By studying these images, we can have a real change in the paradigm of wine history and bring awareness to the influence that Egyptian wine culture had on Mediterranean wine culture.”

As early as the Predynastic period, beginning in the mid-fifth millennium B.C., the Egyptians placed wine jars in tombs as offerings to the dead. References to wine dating to the 1st and 2nd Dynasties have been identified on ceramic jar seals found in the burial grounds at Abydos and Saqqara, and the word for wine, “irp,” appears on 2nd Dynasty stelas. By the 4th Dynasty, in the mid-third millennium B.C., tomb designers had begun to illustrate viticulture and winemaking on tomb walls. For archaeologist Sofia Fonseca of the Autonomous University of Barcelona, such imagery offers valuable insights into the vintner’s entire process. “We have this idea that viticulture and winemaking originated in the ancient Near East, and that European wine culture is a legacy from Greece and Rome,” she says. “But the truth is that, starting more than 4,500 years ago, and for the next two millennia of Egyptian history, we have images that show a traditional process similar to those winemakers in Mediterranean regions are still using. By studying these images, we can have a real change in the paradigm of wine history and bring awareness to the influence that Egyptian wine culture had on Mediterranean wine culture.”

While the Egyptians drank both red and white wine, only red wine is depicted in the tombs. “It’s interesting to see how the symbolism of wine is deeply related to the color red,” says Fonseca. “This recalls the relationship between wine and the blood of Osiris, the god of death and resurrection, who is called the Lord of Wine in the late Old Kingdom Pyramid Texts. It also recalls the relationship between wine and the reddish color of the Nile during the annual flood, when iron-rich sediment flows into the river from the mountains of Ethiopia at just the time when the grape harvest begins.”

Achaemenid Wine Connoisseurs

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Friday, October 09, 2020

For the kings of the Achaemenid Empire, who ruled much of the ancient Near East from 550 to 330 B.C., there was little—apart from hunting lions and conquering the world—that rivaled a rhyton of fine wine. But for these powerful potentates, wine was not just a pleasurable pastime. It was also not, despite what the fifth-century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus would have people believe, evidence of the kings’ profligate behavior and poor decision-making skills characterized by zealous over-imbibing. “Wine drinking and distribution not only embodied refinement, wealth, and power for the Achaemenids, but also provided an opportunity for rewarding loyalty and implementing political strategy,” says linguist Ashk Dahlén of Uppsala University. “Banquets were inherently public, political acts. They were central to the construction of royal identity and demonstrated that the empire was a supreme player on the world stage.”

For the kings of the Achaemenid Empire, who ruled much of the ancient Near East from 550 to 330 B.C., there was little—apart from hunting lions and conquering the world—that rivaled a rhyton of fine wine. But for these powerful potentates, wine was not just a pleasurable pastime. It was also not, despite what the fifth-century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus would have people believe, evidence of the kings’ profligate behavior and poor decision-making skills characterized by zealous over-imbibing. “Wine drinking and distribution not only embodied refinement, wealth, and power for the Achaemenids, but also provided an opportunity for rewarding loyalty and implementing political strategy,” says linguist Ashk Dahlén of Uppsala University. “Banquets were inherently public, political acts. They were central to the construction of royal identity and demonstrated that the empire was a supreme player on the world stage.”

At such splendid affairs, wine was served by the Royal Cup Bearer, a role known from records such as the Persepolis Administrative Archives to have been one of the highest trust. The bearer would have been an excellent sommelier and, says Dahlén, well versed in different wines and the particular customs associated with them. “The variety of wine at the king’s table was not a matter of sheer self-indulgence,” he says, “but served as a symbol of the king’s power and his capacity to attract tribute.” Unlike Greek symposiums, where the presence of “proper” women was not allowed, in the Achaemenid court, women were fully included, says Dahlén, all part of what he calls the “ancient Iranian dolce vita.”

A Taste for the Exotic

By MARLEY BROWN

Friday, October 09, 2020

Although the ancient city of Xi’an in what is now central China is often considered the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, the flow of goods, people, and ideas between Europe, the Middle East, and Asia did not end there. Drinking vessels that date to Korea’s Goryeo Period (ca. A.D. 918–1392) suggest that imported spirits, including grape wines, a distilled anise-flavored drink called arak, and a fermented dairy product known as kumis, inspired artisans to craft novel types of ceramic containers to hold these newly enjoyed beverages. “New kinds of alcohol led to a proliferation in vessel shapes,” says art historian In-Sung Kim Han of SOAS University of London. She explains that many traditional East Asian alcoholic substances made from grains such as rice, millet, and barley, were thick and porridge-like. Pre-Goryeo vessels uncovered during archaeological excavations, mostly of tombs, suggest that these were primarily consumed from drinking bowls. More delicate cups from the same period were probably reserved for drinking tea and filtered rice wine, which was relatively rare.

Although the ancient city of Xi’an in what is now central China is often considered the eastern terminus of the Silk Road, the flow of goods, people, and ideas between Europe, the Middle East, and Asia did not end there. Drinking vessels that date to Korea’s Goryeo Period (ca. A.D. 918–1392) suggest that imported spirits, including grape wines, a distilled anise-flavored drink called arak, and a fermented dairy product known as kumis, inspired artisans to craft novel types of ceramic containers to hold these newly enjoyed beverages. “New kinds of alcohol led to a proliferation in vessel shapes,” says art historian In-Sung Kim Han of SOAS University of London. She explains that many traditional East Asian alcoholic substances made from grains such as rice, millet, and barley, were thick and porridge-like. Pre-Goryeo vessels uncovered during archaeological excavations, mostly of tombs, suggest that these were primarily consumed from drinking bowls. More delicate cups from the same period were probably reserved for drinking tea and filtered rice wine, which was relatively rare.

Han suggests that while medieval Korea is often thought of as having been closed off to the rest of the world, the Goryeo Kingdom’s contact with nomadic groups to the west kept it in touch with global trends and foreign commodities, including alcoholic beverages. Particularly after the kingdom became part of the Mongol Empire in 1270, elite members of Goryeo society adopted some of the consumption habits of their counterparts across Central Asia and the Islamic world, where alcohol was widely available despite its prohibition in the Koran. One particular type of long-necked bottle introduced during the Goryeo Period, which was used to store wine, appears to have come to Korea from Islamic Persia. “It seems that the tastes of the upper class in any era tend toward the cosmopolitan,” Han says. The Goryeosa, a history of the kingdom compiled in the fifteenth century, describes one Goryeo ruler who began wearing Mongolian clothing, sporting a pigtail hairstyle, and taking part in large-scale hunts, just like other princes across Eurasia. “Despite his courtiers’ criticisms,” Han says, “he and his immediate followers pursued a worldly lifestyle, including enthusiasm for exotic drinks.”

Socializing at the Symposium

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Friday, October 09, 2020

Ancient Greek vases frequently depict the revels of men participating in the symposium, an intimate drinking party held in a private home, as well as the consequences of excessive consumption that may have occurred during such gatherings. But just how much wine, mixed with water in a bowl called a krater, would a group have consumed in the course of a typical symposium in early fifth-century B.C. Athens? To answer this question, archaeologist Kathleen Lynch of the University of Cincinnati and independent scholar Richard Bidgood calculated the capacity of serving vessels and drinking cups, including kylikes and skyphoi, excavated from early fifth-century B.C. houses in the Athenian Agora, the city’s main marketplace. Assuming each kylix was filled to just over half an inch below its rim—a level at which reclining guests could swill, but not spill, their wine—they estimated that the average cup’s capacity was roughly equivalent to that of a can of soda. Thus, a single krater could hold a few rounds of drinks for a moderate-size group.

Ancient Greek vases frequently depict the revels of men participating in the symposium, an intimate drinking party held in a private home, as well as the consequences of excessive consumption that may have occurred during such gatherings. But just how much wine, mixed with water in a bowl called a krater, would a group have consumed in the course of a typical symposium in early fifth-century B.C. Athens? To answer this question, archaeologist Kathleen Lynch of the University of Cincinnati and independent scholar Richard Bidgood calculated the capacity of serving vessels and drinking cups, including kylikes and skyphoi, excavated from early fifth-century B.C. houses in the Athenian Agora, the city’s main marketplace. Assuming each kylix was filled to just over half an inch below its rim—a level at which reclining guests could swill, but not spill, their wine—they estimated that the average cup’s capacity was roughly equivalent to that of a can of soda. Thus, a single krater could hold a few rounds of drinks for a moderate-size group.

Even if the krater were refilled throughout the night, Lynch explains, this suggests that symposiasts wanted to prolong the evening’s festivities without going overboard. The researchers also discovered that kylikes from a given house held varying amounts, even if they appeared to all be around the same size. “The symposium’s emphasis on equality was underscored by everyone having the perception of the same amount of wine,” says Lynch. “Even if it was technically a bit different, they wanted to look around the room and see people with similar-size cups filled to a similar level, so that no one felt that somebody was getting too much.”

Forging Wari Alliances

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Friday, October 09, 2020

High atop a mountain in southern Peru, leaders at the remote administrative center of Cerro Baúl once entertained local elites with elaborate feasts that helped sustain the Wari Empire from about A.D. 600 to 1000. Central to these gatherings was the ceremonial drinking of chicha, a typically corn-based fermented beverage. Based on the size of the spaces where the feasts took place, archaeologists think that they held 50 to 100 guests who imbibed chicha from vibrantly painted ceramic cups. These cups ranged in size to reflect the status of the drinkers and were decorated with images of Wari heroes and gods, such as the Front-Facing Deity, and more local stylistic flourishes, including llamas adorning the deities’ faces. “One of the most effective ways to bring local elites into the hierarchy of the empire was through drinking Wari beer the Wari way,” says archaeologist Donna Nash of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, who codirects excavations at Cerro Baúl with archaeologist Ryan Williams of the Field Museum. “Many of the stories, songs, and ideas that went with that probably would have been expressed using the iconography on the vessels guests were drinking from.”

High atop a mountain in southern Peru, leaders at the remote administrative center of Cerro Baúl once entertained local elites with elaborate feasts that helped sustain the Wari Empire from about A.D. 600 to 1000. Central to these gatherings was the ceremonial drinking of chicha, a typically corn-based fermented beverage. Based on the size of the spaces where the feasts took place, archaeologists think that they held 50 to 100 guests who imbibed chicha from vibrantly painted ceramic cups. These cups ranged in size to reflect the status of the drinkers and were decorated with images of Wari heroes and gods, such as the Front-Facing Deity, and more local stylistic flourishes, including llamas adorning the deities’ faces. “One of the most effective ways to bring local elites into the hierarchy of the empire was through drinking Wari beer the Wari way,” says archaeologist Donna Nash of the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, who codirects excavations at Cerro Baúl with archaeologist Ryan Williams of the Field Museum. “Many of the stories, songs, and ideas that went with that probably would have been expressed using the iconography on the vessels guests were drinking from.”

Because Cerro Baúl was a provincial outpost on the empire’s edge, the Wari relied on local resources and on-site brewing to maintain a steady flow of chicha. Nash and Williams have unearthed a large brewery where high-status Wari women ground, boiled, and fermented corn and other ingredients to produce the beverage. Analysis of residue extracted from drinking cups, serving vessels, and oversize storage jars from the brewery’s fermentation room indicate that the drink was likely a mixture of corn and molle, or Peruvian pepper tree berries, whose seeds the archaeologists found in large quantities in the brewery’s trash pits. Although the Wari at Cerro Baúl didn’t have direct access to fresh water, the region’s temperate climate was a boon for chicha production, even during more arid periods. “Molle berries produce year-round in this environment,” says Williams. “Corn can be double or triple cropped, so you can get two to three times the corn from a single year’s harvest.”

The Wari’s self-sufficiency ensured that feasting events could continue regardless of political disruptions or trade delays elsewhere in the empire. The archaeologists have determined that even the cups the Wari used were made in a ceramic workshop on the mountaintop using high-quality clay from a source they controlled across the valley, rather than imported from the distant imperial capital.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement