Top 10

Mummy Cache

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Friday, December 04, 2020

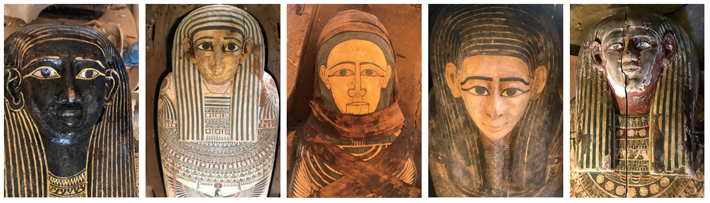

Within three deep burial shafts in a section of the Saqqara necropolis known as the Area of Sacred Animals, archaeologists have unearthed 100 vividly painted wooden coffins containing the mummified remains of individuals who traveled to the afterlife some 2,500 years ago. The sealed sarcophagi were found stacked atop one another alongside 40 statues of the funerary deity Ptah-Sokar-Osiris and a bronze sculpture of the lotus-flower god Nefertum. Although the shafts were reopened multiple times in antiquity to inter more people, researchers have dated all the burials to the 26th Dynasty (688–525 B.C.) based on names inscribed on the coffins. “These kinds of shafts, which contain many burials, possibly for a family or group, were common during this period,” says Mostafa Waziri, secretary-general of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities. “We think that the owners of these coffins are the priests and high officials of the temple of the cat goddess, Bastet.”

Within three deep burial shafts in a section of the Saqqara necropolis known as the Area of Sacred Animals, archaeologists have unearthed 100 vividly painted wooden coffins containing the mummified remains of individuals who traveled to the afterlife some 2,500 years ago. The sealed sarcophagi were found stacked atop one another alongside 40 statues of the funerary deity Ptah-Sokar-Osiris and a bronze sculpture of the lotus-flower god Nefertum. Although the shafts were reopened multiple times in antiquity to inter more people, researchers have dated all the burials to the 26th Dynasty (688–525 B.C.) based on names inscribed on the coffins. “These kinds of shafts, which contain many burials, possibly for a family or group, were common during this period,” says Mostafa Waziri, secretary-general of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities. “We think that the owners of these coffins are the priests and high officials of the temple of the cat goddess, Bastet.”

Carbon Dating Pottery

By ZACH ZORICH

Friday, December 04, 2020

Since the 1990s, biogeochemist Richard Evershed of the University of Bristol has been trying to find a way to accurately radiocarbon date ceramic artifacts. But it has taken nearly three decades for technology to catch up with his vision. Archaeologists have been using pottery styles to date artifacts and sites for decades, but these dates had to be confirmed using methods such as radiocarbon dating of associated materials or dendrochronology, the analysis of tree rings. Evershed’s new technique allows researchers to directly radiocarbon date animal fat residue on pottery. His team is able to isolate compounds from samples of pottery that weigh as little as two grams and to detect the minuscule amount of fatty-acid carbon remaining in the residues left by milk, cheese, or meat.

Since the 1990s, biogeochemist Richard Evershed of the University of Bristol has been trying to find a way to accurately radiocarbon date ceramic artifacts. But it has taken nearly three decades for technology to catch up with his vision. Archaeologists have been using pottery styles to date artifacts and sites for decades, but these dates had to be confirmed using methods such as radiocarbon dating of associated materials or dendrochronology, the analysis of tree rings. Evershed’s new technique allows researchers to directly radiocarbon date animal fat residue on pottery. His team is able to isolate compounds from samples of pottery that weigh as little as two grams and to detect the minuscule amount of fatty-acid carbon remaining in the residues left by milk, cheese, or meat.

Being able to directly date pottery in this way offers archaeologists a novel option. “It gives you a new anchor point,” says Evershed. As proof of concept, his team used the method at sites with well-established chronologies. One of these is an elevated wooden path that ran through a wetland in Somerset, England, known as the Sweet Track site. Dendrochronology carried out in the 1980s had previously revealed that construction of the track began in the winter of 3807 B.C. Dates from pottery found near the track matched the date obtained through dendrochronology. At the early Neolithic (ca. 6700–5650 B.C.) site of Çatalhöyük in Turkey, dates from four pottery sherds also matched the site’s known chronology. Evershed hopes the technique will allow researchers to learn more about the origins of animal domestication. It could also reveal when changes in prehistoric diets, such as the adoption of dairy products, took place. The best part, says Evershed, is that pottery is found all over the world and, therefore, “it’s a technique that could be applied anywhere, to any culture.”

The First Enslaved Africans in Mexico

By MARLEY BROWN

Friday, December 04, 2020

Details from the lives of three young men buried in a sixteenth-century mass grave in Mexico City have finally been brought to light by researchers who conducted isotope, genetic, and osteological analysis of their remains. Most notably, all three appear to have been born in West Africa. The men’s teeth were filed into shapes similar to those described by contemporaneous European travelers to West Africa and to dental modifications still performed by some groups in the region today. The skeletons were originally discovered in the 1980s, when subway construction revealed a colonial-era hospital for Indigenous people. “We know there were a large number of Africans who were abducted and transported to New Spain, but they did not generally live in Mexico City,” says archaeogeneticist Rodrigo Barquera of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. “That’s why it’s surprising to find these three individuals there.”

Details from the lives of three young men buried in a sixteenth-century mass grave in Mexico City have finally been brought to light by researchers who conducted isotope, genetic, and osteological analysis of their remains. Most notably, all three appear to have been born in West Africa. The men’s teeth were filed into shapes similar to those described by contemporaneous European travelers to West Africa and to dental modifications still performed by some groups in the region today. The skeletons were originally discovered in the 1980s, when subway construction revealed a colonial-era hospital for Indigenous people. “We know there were a large number of Africans who were abducted and transported to New Spain, but they did not generally live in Mexico City,” says archaeogeneticist Rodrigo Barquera of the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History. “That’s why it’s surprising to find these three individuals there.”

The skeletons also show evidence of strenuous physical labor and violent trauma. According to Barquera, the men were likely among the first generation of enslaved Africans brought to coastal Mexico in the 1520s. They may have toiled on a sugar plantation or in a mine before possibly becoming sick during an epidemic, which could explain their presence at the hospital. Isotope analysis of their teeth—which can determine where a person originated and what kind of food they consumed as a child—was consistent with West African ecosystems, and their DNA revealed that all three shared West African ancestry. However, the men weren’t related to each other, and the team couldn’t connect them to a specific population. It is possible, Barquera explains, that “after the community in Africa was raided, it disappeared from the historical record.”

Largest Viking DNA Study

By JASON URBANUS

Friday, December 04, 2020

The largest-ever study of Viking DNA has revealed a wealth of information, offering new insights into the Vikings’ genetic diversity and travel habits. The ambitious research analyzed DNA taken from 442 skeletons discovered at more than 80 Viking sites across northern Europe and Greenland. The genomes were then compared with a genetic database of thousands of present-day individuals to try to ascertain who the Vikings really were and where they ventured. One of the project’s primary objectives was to better understand the Viking diaspora, says University of California, Berkeley, geneticist Rasmus Nielsen.

The largest-ever study of Viking DNA has revealed a wealth of information, offering new insights into the Vikings’ genetic diversity and travel habits. The ambitious research analyzed DNA taken from 442 skeletons discovered at more than 80 Viking sites across northern Europe and Greenland. The genomes were then compared with a genetic database of thousands of present-day individuals to try to ascertain who the Vikings really were and where they ventured. One of the project’s primary objectives was to better understand the Viking diaspora, says University of California, Berkeley, geneticist Rasmus Nielsen.

It turns out that the roving bands of raiders and traders, traditionally thought to have come only from Norway, Denmark, and Sweden, were far more genetically diverse than expected. According to Eske Willerslev of the University of Copenhagen, one of the most unexpected results was that the Viking Age of exploration may have actually been driven by outsiders. The researchers found that just prior to the Viking Age and during its height, between A.D. 800 and 1050, genes flowed into Scandinavia from people arriving there from eastern and southern Europe, and even from western Asia. In contrast to the traditional image of the light-haired, light-eyed Viking, the genetic evidence shows that dark hair and eyes were far more common among Scandinavians of the Viking Age than they are today. “Vikings were not restricted to genetically pure Scandinavians,” says Willerslev, “but were a diverse group of peoples with diverse ancestry.” In fact, some who adopted the trappings of Viking identity were not Scandinavian at all. For example, two individuals who were buried in Scotland’s Orkney Islands with Viking grave goods and in traditional Viking style were, surprisingly, determined to be genetically linked to the Picts of Scotland and contemporaneous inhabitants of Ireland.

Viking raiding parties departing from a given country, the study found, tended to journey consistently to a particular destination. Expeditions from Sweden usually went eastward to the Baltic states, Poland, and Ukraine; Vikings from Norway tended to sail to Iceland, Greenland, and Ireland; and those from Denmark predominantly ventured to England. The study also determined that Viking expeditions sometimes comprised a group of close-knit, even related, individuals. Analysis of 41 skeletons from two ship burials in Salme, Estonia, indicates that they likely hailed from a small village in Sweden, and that four were brothers, entombed alongside one another. (To read a full-length article about Salme, go to “The First Vikings.”)

Luwian Royal Inscription

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Friday, December 04, 2020

While conducting a surface survey of the ancient mound site of Türkmen-Karahöyük in southern Turkey, a team led by archaeologists James Osborne and Michele Massa of the University of Chicago made a surprising discovery in a canal not far from the mound: a stone stela bearing hieroglyphs in Luwian, a relative of the Hittite language. Based on the shapes of the glyphs, the inscription has been dated to the eighth century B.C. It records the military achievements of “Great King Hartapu,” a ruler previously known only from inscriptions found at two nearby hilltop sanctuaries. Those enigmatic monuments offer no details about the dates of his reign or the extent of his realm. The new inscription, Osborne explains, establishes Hartapu as a Neo-Hittite leader who claims to have conquered the wealthy kingdom of Phrygia in west-central Anatolia and, in a single year, to have defeated a coalition of 13 kings. “We now know almost certainly that Hartapu’s capital city was Türkmen-Karahöyük and that he was allegedly powerful enough to defeat Phrygia in battle when it was at its height,” Osborne says. “Hartapu wasn’t a local yokel, he was apparently a major Iron Age player.”

While conducting a surface survey of the ancient mound site of Türkmen-Karahöyük in southern Turkey, a team led by archaeologists James Osborne and Michele Massa of the University of Chicago made a surprising discovery in a canal not far from the mound: a stone stela bearing hieroglyphs in Luwian, a relative of the Hittite language. Based on the shapes of the glyphs, the inscription has been dated to the eighth century B.C. It records the military achievements of “Great King Hartapu,” a ruler previously known only from inscriptions found at two nearby hilltop sanctuaries. Those enigmatic monuments offer no details about the dates of his reign or the extent of his realm. The new inscription, Osborne explains, establishes Hartapu as a Neo-Hittite leader who claims to have conquered the wealthy kingdom of Phrygia in west-central Anatolia and, in a single year, to have defeated a coalition of 13 kings. “We now know almost certainly that Hartapu’s capital city was Türkmen-Karahöyük and that he was allegedly powerful enough to defeat Phrygia in battle when it was at its height,” Osborne says. “Hartapu wasn’t a local yokel, he was apparently a major Iron Age player.”

Based on the ceramics they recovered from the mound, the researchers have determined that, by around 1400 B.C., Türkmen-Karahöyük had grown from a small settlement to a regional center sprawling over more than 300 acres. During the succeeding centuries and throughout Hartapu’s reign, Osborne says, the city probably continued to be one of the largest in Anatolia. “Even in a country as archaeologically diverse as Turkey,” he says, “it’s not every day that an archaeologist finds a massive Bronze and Iron Age city that has never been touched.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement