Features

The Visigoths' Imperial Ambitions

By JASON URBANUS

Tuesday, March 23, 2021

Most historians and archaeologists agree: The sixth century A.D. was not an easy time to be alive. The Western Roman Empire had collapsed in the previous century, plunging much of the continent into economic, political, and social upheaval. On top of this, the first outbreak and frequent recurrence of bubonic plague resulted in the estimated deaths of millions. Making matters even worse, a series of volcanic eruptions caused climatic changes from Britain to China, ushering in a cooling period known as the Late Antique Little Ice Age. Recent studies have indicated that this caused drought, crop failure, breakdown in food supply chains, and famine. Harvard University medieval historian Michael McCormick has gone so far as to characterize the period following a particularly intense volcanic eruption in A.D. 536 as one of the single worst eras in recorded human history.

One consequence of this turmoil was that, across most of Europe, many urban centers deteriorated, a process that had begun a few centuries earlier when the Roman state first started to weaken. Cities and towns, once hallmarks of the Roman world and essential instruments of the Roman administrative system, were increasingly abandoned. Masses fled to the countryside seeking survival. Western civilization was irrevocably transformed.

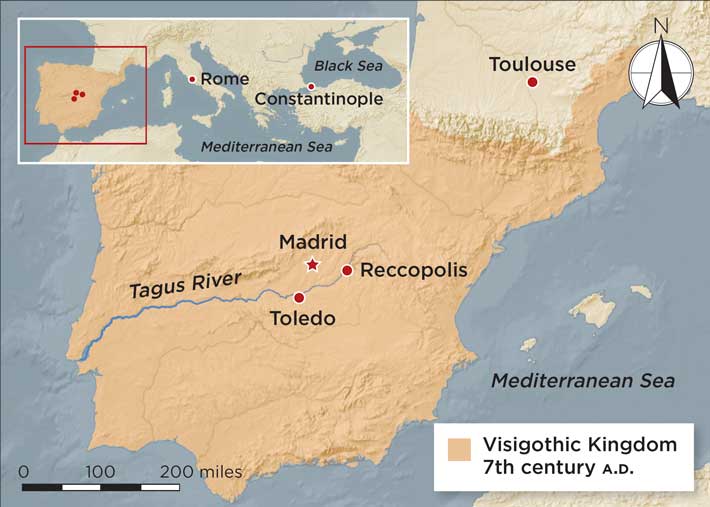

However, recent archaeological work in Iberia, on the periphery of the former Roman Empire, conveys a different story. It is revealing how, against this backdrop of chaos, a people emerged who succeeded in founding perhaps the strongest kingdom in the post-Roman world. These were the Visigoths, who had first arrived in Iberia in the A.D. 410s, when Roman rule was crumbling. Over the next two centuries the Visigoths unified a politically fractured landscape, bringing a semblance of stability to a region racked by centuries of violence and uncertainty. They implemented new taxation and legal systems and reestablished trade with the broader Mediterranean world. The Visigoths also did the seemingly impossible—in a largely deurbanized world, they began to build cities. Written sources suggest that the Visigoths founded at least four new urban centers, but only one of them, Reccopolis, can be identified with certainty. It was one of the crowning achievements of King Leovigild (r. A.D. 568–586), perhaps the Visigoths’ greatest ruler. Today, Reccopolis is an unlikely example of a post-Roman urban settlement that arose amid the disorder and uncertainty of sixth-century Europe. “One does not see many new towns founded during this period elsewhere in the Mediterranean,” says McCormick. “It is quite surprising.”

One Visigothic chronicler, John of Biclaro, records that Leovigild founded Reccopolis in A.D. 578 and furnished it with “splendid buildings.” Today, the remains of these buildings sit atop a plateau that rises above the banks of the Tagus River in the central Spanish province of Guadalajara. Although Reccopolis is less than a two-hour drive from Madrid, parts of this province have in recent years become some of the most desolate in all of Europe due to financial crises and a dearth of economic opportunities for its rural population. However, 1,400 years ago, the opposite process was underway. The establishment of a Visigothic settlement in the region attracted throngs of people who settled within the new town and formed satellite communities in its vicinity.

One Visigothic chronicler, John of Biclaro, records that Leovigild founded Reccopolis in A.D. 578 and furnished it with “splendid buildings.” Today, the remains of these buildings sit atop a plateau that rises above the banks of the Tagus River in the central Spanish province of Guadalajara. Although Reccopolis is less than a two-hour drive from Madrid, parts of this province have in recent years become some of the most desolate in all of Europe due to financial crises and a dearth of economic opportunities for its rural population. However, 1,400 years ago, the opposite process was underway. The establishment of a Visigothic settlement in the region attracted throngs of people who settled within the new town and formed satellite communities in its vicinity.

The Amazing True Story of Nathan Harrison

By DANIEL WEISS

Thursday, February 11, 2021

Around the turn of the twentieth century, Palomar Mountain became a popular destination for tourists from San Diego. Though the mountain lies just 60 miles northeast of the city, at the time, the arduous trip to its summit took several days via horse, horse-drawn carriage, or automobile. The final six miles to its 6,140-foot peak, up a winding grade from the mountain’s base, known as Tin Can Flat, took a full day. The single-lane, unpaved track ran alongside sheer drop-offs and was so steep that drivers would often tie trees to their bumpers for the descent in an attempt to spare their brakes. On the dry, dusty way up, it wasn’t long before the horses were panting for water and the Model T radiators were bone dry. So it was with great relief that, two-thirds of the way up the slope, travelers would come upon a spring attended by an aged African American man named Nathan Harrison.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, Palomar Mountain became a popular destination for tourists from San Diego. Though the mountain lies just 60 miles northeast of the city, at the time, the arduous trip to its summit took several days via horse, horse-drawn carriage, or automobile. The final six miles to its 6,140-foot peak, up a winding grade from the mountain’s base, known as Tin Can Flat, took a full day. The single-lane, unpaved track ran alongside sheer drop-offs and was so steep that drivers would often tie trees to their bumpers for the descent in an attempt to spare their brakes. On the dry, dusty way up, it wasn’t long before the horses were panting for water and the Model T radiators were bone dry. So it was with great relief that, two-thirds of the way up the slope, travelers would come upon a spring attended by an aged African American man named Nathan Harrison.

Harrison greeted the travelers with a wide grin and a plentiful supply of water to slake the thirst of man, woman, horse, and car. Then, speaking in a thick accent that nodded to his origins in Southern slavery, he would regale visitors with tales of his life on the mountain. This was a world of grizzly bears that could chew wooden traps to pieces. “When I first came to the mountain, bear were thick,” Harrison once recalled to Robert Asher, one of his neighbors on Palomar. “You could just hear them poppin’ their teeth.” There were mountain lions that leapt upwards of 35 feet—including one Harrison claimed to have taken down that measured “fourteen feet seven inches from tip to tip.” In addition to harrowing run-ins with these wild predators, Harrison told of his confrontations with rustlers who aimed to poach his ample stock of horses, cattle, and sheep.

Many of Harrison’s stories had the air of embellishment—he even told a few children he’d come to California in 1849 by boat, braving the treacherous waters around Cape Horn. Despite the improbability of his tales, or perhaps because of it, Harrison’s audience of white San Diegans exploring the wilderness just outside their city lapped it up. When they returned home, they told others of their encounters with Harrison, and before long, he was one of the highlights of a trip up Palomar Mountain. (See “The Birth of Western Tourism.”) “Visiting Harrison was like stepping into a time machine and going back to the Old South,” says Seth Mallios, an archaeologist at San Diego State University. “People were magically transported back fifty years and three thousand miles away.”

Many of Harrison’s stories had the air of embellishment—he even told a few children he’d come to California in 1849 by boat, braving the treacherous waters around Cape Horn. Despite the improbability of his tales, or perhaps because of it, Harrison’s audience of white San Diegans exploring the wilderness just outside their city lapped it up. When they returned home, they told others of their encounters with Harrison, and before long, he was one of the highlights of a trip up Palomar Mountain. (See “The Birth of Western Tourism.”) “Visiting Harrison was like stepping into a time machine and going back to the Old South,” says Seth Mallios, an archaeologist at San Diego State University. “People were magically transported back fifty years and three thousand miles away.”

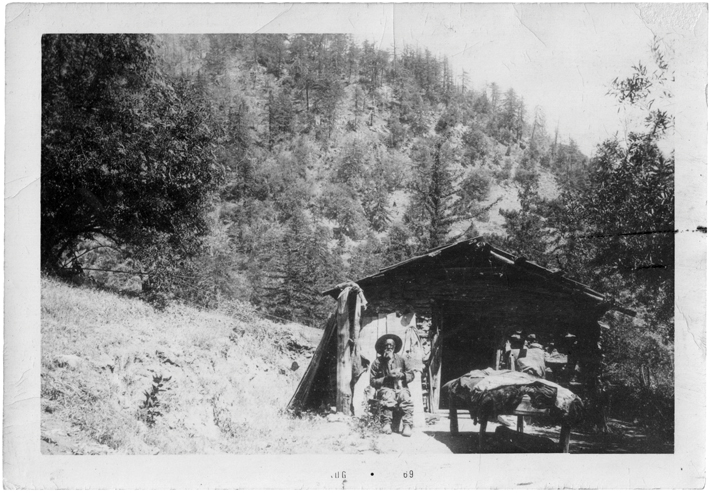

Harrison would often invite travelers to his cabin for further entertainment. Allan Kelly, who trekked up the mountain with his family in 1908 when he was seven years old, later recalled, “He had a lovely spot: a far distant view to the ocean…about an acre of good soil for a garden and a few apple and pear trees.” In exchange for Harrison’s hospitality, the visiting city folk came bearing gifts—typically tins of meat, bottles of alcohol, and clothing. Many also brought along early Kodak Brownie cameras to capture snapshots of their host. Although he lived in a relatively remote location, Harrison was likely the most frequently photographed person of his time in the San Diego area, suggests Mallios, who has extensively researched Harrison’s life and leads excavations of the site where his cabin once stood. “There was nothing convenient about taking his photograph,” says Mallios. “People were aware that he was someone they wanted to take a photo of, whether it was to show that they had made it to the top of this very perilous mountain, or to capture something that you just didn’t see anywhere else.”

In these photographs, and when entertaining visitors, Harrison came across as exceedingly humble. A scraggly white beard hung from his chin, and he wore tattered clothes—his friend Robert Asher reported that he once deliberately changed into his most ragged pair of overalls before being photographed. Whereas a typical rancher of his time would carry a rifle and warily approach visitors on horseback, Harrison greeted tourists unarmed and on foot, aided by a walking stick. “He was very charismatic, smiling,” says Mallios. “He made fun of himself and couldn’t have been less threatening.” However, as he continued to learn about Harrison, Mallios found that there was far more to the mountain man—and the ways in which he managed to prosper—than first met the eye.

|

Sidebar:

|

The Birth of Western Tourism

|

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

The Amazing True Story of Nathan Harrison

The Visigoths' Imperial Ambitions

Letter from Chihuahua

Digs & Discoveries

An Enduring Design

The Mummies Return

A Dutiful Roman Soldier

In Full Plume

Joust Like a King

Temple of Heaven

Lady Killer

More Vesuvius Victims

Flower Child

Tyrrhenian Traders

Off the Grid

Around the World

Neanderthal burial practices, Mexican marigold, Levantine bananas, and defending a Phoenician colony

Artifact

Ancient athletic accoutrements

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

The walls and roofs of Reccopolis’ enormous palatine complex once towered high above the countryside, a ubiquitously visible symbol of the rising Visigothic state. Built on the city’s highest ground, this urban district served as the seat of the new Visigothic monarchy and administration. A church, one of the largest in Iberia at the time, was located across a large open plaza. A monumental gateway would have ushered people out of this district and onto a street full of shops and houses. Reccopolis was, by all accounts, a wealthy and vibrant city that was bustling in a way that very few others in Europe were. Yet, less than 250 years later, Reccopolis was nearly empty. Its building materials were hauled away to construct a new settlement, and over the subsequent centuries the once-great Visigothic city disappeared from view, receding into the surrounding agricultural fields.

The walls and roofs of Reccopolis’ enormous palatine complex once towered high above the countryside, a ubiquitously visible symbol of the rising Visigothic state. Built on the city’s highest ground, this urban district served as the seat of the new Visigothic monarchy and administration. A church, one of the largest in Iberia at the time, was located across a large open plaza. A monumental gateway would have ushered people out of this district and onto a street full of shops and houses. Reccopolis was, by all accounts, a wealthy and vibrant city that was bustling in a way that very few others in Europe were. Yet, less than 250 years later, Reccopolis was nearly empty. Its building materials were hauled away to construct a new settlement, and over the subsequent centuries the once-great Visigothic city disappeared from view, receding into the surrounding agricultural fields. The ruins of Reccopolis were located in the 1890s, but archaeological excavations did not begin until the mid-twentieth century. Work continued sporadically for decades, until interest began to intensify in the 1990s under the leadership of University of Alcalá archaeologist Lauro Olmo-Enciso. For more than two decades, Olmo-Enciso’s projects have continued to uncover parts of the ancient settlement that are not only leading to a new understanding of Visigothic cities, but also to a clearer picture of the physical and political landscape of post-Roman Iberia. “Reccopolis now stands as an exceptional example of early medieval urbanism that challenges our perceptions of urban development in sixth-century Europe,” Olmo-Enciso says. He and his team have learned just how integral urban centers such as Reccopolis were to the rulers of the Visigothic Kingdom, and especially to Leovigild. As it happens, the construction of Reccopolis was a strategic play that the king borrowed from the political handbook used by Roman emperors—the Visigoths’ old rivals—for centuries.

The ruins of Reccopolis were located in the 1890s, but archaeological excavations did not begin until the mid-twentieth century. Work continued sporadically for decades, until interest began to intensify in the 1990s under the leadership of University of Alcalá archaeologist Lauro Olmo-Enciso. For more than two decades, Olmo-Enciso’s projects have continued to uncover parts of the ancient settlement that are not only leading to a new understanding of Visigothic cities, but also to a clearer picture of the physical and political landscape of post-Roman Iberia. “Reccopolis now stands as an exceptional example of early medieval urbanism that challenges our perceptions of urban development in sixth-century Europe,” Olmo-Enciso says. He and his team have learned just how integral urban centers such as Reccopolis were to the rulers of the Visigothic Kingdom, and especially to Leovigild. As it happens, the construction of Reccopolis was a strategic play that the king borrowed from the political handbook used by Roman emperors—the Visigoths’ old rivals—for centuries. In the more than six centuries during which the Romans ruled in Iberia, they transformed the peninsula into one of the most urbanized territories in the empire. But by the late sixth century only a handful of functioning cities remained. As Visigothic monarchs became more powerful, they began to revitalize cities and towns. Some effort was put into renovating and expanding already established centers such as Toledo, which became the capital of the new Visigothic Kingdom, but Leovigild and his successors also set out to build brand-new cities, an ambitious enterprise given the crisis conditions in most of Europe. “In the later sixth century, there were a startling number of developments which occurred that might seem unfavorable to creating new cities,” McCormick says.

In the more than six centuries during which the Romans ruled in Iberia, they transformed the peninsula into one of the most urbanized territories in the empire. But by the late sixth century only a handful of functioning cities remained. As Visigothic monarchs became more powerful, they began to revitalize cities and towns. Some effort was put into renovating and expanding already established centers such as Toledo, which became the capital of the new Visigothic Kingdom, but Leovigild and his successors also set out to build brand-new cities, an ambitious enterprise given the crisis conditions in most of Europe. “In the later sixth century, there were a startling number of developments which occurred that might seem unfavorable to creating new cities,” McCormick says. Excavations outside the palatine complex have uncovered parts of the city featuring houses and industrial properties belonging to Reccopolis’ residents, artisans, and workers that underscore the city’s important role as a major fiscal and production center. Reccopolis was one of the few places in the Visigothic Kingdom that had its own mint, which issued gold coins on the crown’s behalf. Its main street was lined with shops, warehouses, and commercial establishments. There were two glass-blowing studios as well as a goldsmith’s workshop where archaeologists found scales and molds for crafting rings and earrings. Vendors sold imported luxury items, indicating that Reccopolis’ merchants were once again connected to broader Mediterranean trade markets, which had been largely closed off after Rome’s withdrawal from Iberia. “It is the richest collection of imports in the center of the Iberian Peninsula,” Olmo-Enciso says. “This shows that aristocrats and elites in Reccopolis had access to Mediterranean consumer goods.”

Excavations outside the palatine complex have uncovered parts of the city featuring houses and industrial properties belonging to Reccopolis’ residents, artisans, and workers that underscore the city’s important role as a major fiscal and production center. Reccopolis was one of the few places in the Visigothic Kingdom that had its own mint, which issued gold coins on the crown’s behalf. Its main street was lined with shops, warehouses, and commercial establishments. There were two glass-blowing studios as well as a goldsmith’s workshop where archaeologists found scales and molds for crafting rings and earrings. Vendors sold imported luxury items, indicating that Reccopolis’ merchants were once again connected to broader Mediterranean trade markets, which had been largely closed off after Rome’s withdrawal from Iberia. “It is the richest collection of imports in the center of the Iberian Peninsula,” Olmo-Enciso says. “This shows that aristocrats and elites in Reccopolis had access to Mediterranean consumer goods.” First and foremost, Leovigild needed Reccopolis to help him maintain control over rural parts of the kingdom. “New urban foundations were established in areas where the monarchy had direct political interest and where there were no functional cities,” says Martínez Jiménez. “For the monarchy, cities were essential to the administration of the territory.” City building was also a huge financial, technological, and logistical undertaking and, as such, was extremely useful for benefactors’ self-promotion. A ruler had to secure the finances, the building materials, the labor force, the engineers, and a checklist of other items in order to pull off constructing and successfully maintaining a new city. “In the context of Central and Western Europe, the Visigothic Kingdom was the only one capable of undertaking operations of great importance such as the founding of a city,” Olmo-Enciso says. Leovigild also wanted something extraordinary to celebrate his tenth anniversary as ruler and his nascent and increasingly powerful Visigothic Kingdom. “If the monarchy needed to make a statement, it needed to have a city,” says Martínez Jiménez. “In addition to imposing control in a key territory in the core of the kingdom, there is a very important propagandistic component to Reccopolis.”

First and foremost, Leovigild needed Reccopolis to help him maintain control over rural parts of the kingdom. “New urban foundations were established in areas where the monarchy had direct political interest and where there were no functional cities,” says Martínez Jiménez. “For the monarchy, cities were essential to the administration of the territory.” City building was also a huge financial, technological, and logistical undertaking and, as such, was extremely useful for benefactors’ self-promotion. A ruler had to secure the finances, the building materials, the labor force, the engineers, and a checklist of other items in order to pull off constructing and successfully maintaining a new city. “In the context of Central and Western Europe, the Visigothic Kingdom was the only one capable of undertaking operations of great importance such as the founding of a city,” Olmo-Enciso says. Leovigild also wanted something extraordinary to celebrate his tenth anniversary as ruler and his nascent and increasingly powerful Visigothic Kingdom. “If the monarchy needed to make a statement, it needed to have a city,” says Martínez Jiménez. “In addition to imposing control in a key territory in the core of the kingdom, there is a very important propagandistic component to Reccopolis.” For Leovigild, there was an additional reason he needed to build a new city—it was what Roman emperors did. Although the Romans were their rivals, the Visigoths were nevertheless heavily influenced by the empire’s culture and symbols. After his rise to power, Leovigild began to portray himself in the manner of Byzantine emperors, adopting the clothing and royal vestments of his eastern counterparts. On coins that he had minted, he depicted himself wearing a diadem and a mantle, in the fashion of Byzantine rulers. For centuries, Roman emperors had built new cities or renamed existing ones after themselves or members of the imperial family as a way of advertising their authority and stamping their name on their territory.

For Leovigild, there was an additional reason he needed to build a new city—it was what Roman emperors did. Although the Romans were their rivals, the Visigoths were nevertheless heavily influenced by the empire’s culture and symbols. After his rise to power, Leovigild began to portray himself in the manner of Byzantine emperors, adopting the clothing and royal vestments of his eastern counterparts. On coins that he had minted, he depicted himself wearing a diadem and a mantle, in the fashion of Byzantine rulers. For centuries, Roman emperors had built new cities or renamed existing ones after themselves or members of the imperial family as a way of advertising their authority and stamping their name on their territory. McCormick and Olmo-Enciso recently used noninvasive geophysical methods to investigate what might be buried beneath the rest of the site. To their surprise, the images revealed additional streets, clusters of buildings, houses, terrace walls, and water channels, all of which are evidence of Reccopolis’ urban sprawl. They even identified a new sector of buildings belonging to the palatine complex. “We were all stunned to discover this completely unknown new quarter,” McCormick says. “Most of the area inside the walls had buildings, showing that this was a built-up town of significant dimensions for this period.”

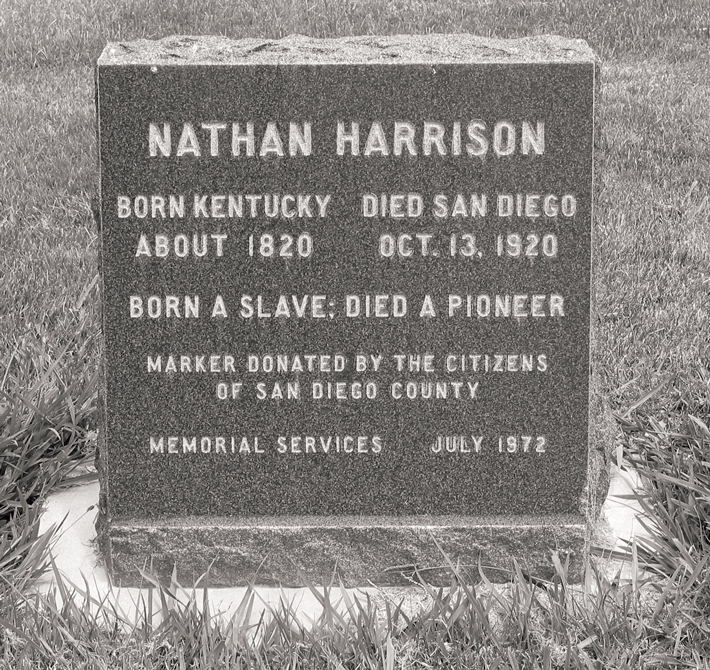

McCormick and Olmo-Enciso recently used noninvasive geophysical methods to investigate what might be buried beneath the rest of the site. To their surprise, the images revealed additional streets, clusters of buildings, houses, terrace walls, and water channels, all of which are evidence of Reccopolis’ urban sprawl. They even identified a new sector of buildings belonging to the palatine complex. “We were all stunned to discover this completely unknown new quarter,” McCormick says. “Most of the area inside the walls had buildings, showing that this was a built-up town of significant dimensions for this period.” Many accounts of Harrison’s life and adventures have been written, beginning when he was still alive and continuing long after he died in 1920. They tend to agree that he was born into slavery and eventually made his way to the San Diego area, becoming the region’s first African American homesteader. Between these two events, various tellers have claimed, apocryphally, that he daringly escaped slavery by floating down the Mississippi River on a raft in the 1840s, à la Huckleberry Finn and Jim; that he helped win California from Mexico by fighting in the 1846 Bear Flag Revolt; and that he drove the first wagon train over Tejon Pass in 1854, opening the route that connected California’s Central Valley with Southern California.

Many accounts of Harrison’s life and adventures have been written, beginning when he was still alive and continuing long after he died in 1920. They tend to agree that he was born into slavery and eventually made his way to the San Diego area, becoming the region’s first African American homesteader. Between these two events, various tellers have claimed, apocryphally, that he daringly escaped slavery by floating down the Mississippi River on a raft in the 1840s, à la Huckleberry Finn and Jim; that he helped win California from Mexico by fighting in the 1846 Bear Flag Revolt; and that he drove the first wagon train over Tejon Pass in 1854, opening the route that connected California’s Central Valley with Southern California. In excavations of the site of Harrison’s cabin launched in 2004, a team led by Mallios has uncovered plentiful evidence of his interactions with tourists. “In multiple records from the 1900s, they talk about the standard kit that you bring to Harrison: a pair of pants, a tin of food, and a bottle of alcohol,” he says. The excavations, in fact, have turned up more than 200 mismatched clothing buttons, a large number of meat tins, and liquor bottles from all over the world. The sheer number of buttons is particularly impressive. “If this were some other site,” Mallios says, “we might have concluded that there were a dozen people living here with how many buttons were there.”

In excavations of the site of Harrison’s cabin launched in 2004, a team led by Mallios has uncovered plentiful evidence of his interactions with tourists. “In multiple records from the 1900s, they talk about the standard kit that you bring to Harrison: a pair of pants, a tin of food, and a bottle of alcohol,” he says. The excavations, in fact, have turned up more than 200 mismatched clothing buttons, a large number of meat tins, and liquor bottles from all over the world. The sheer number of buttons is particularly impressive. “If this were some other site,” Mallios says, “we might have concluded that there were a dozen people living here with how many buttons were there.” The archaeologists also unearthed a small piece of convex glass with a ridged nickel edge that puzzled them at first, until they realized it was the lens from a Kodak Brownie camera. And, buried under the patio of Harrison’s cabin were a number of extremely deteriorated automobile inner tubes dating to the 1910s. He had apparently stowed supplies that might prove useful for those attempting the challenging drive up the mountain. In a sense, Mallios points out, Harrison was analogous to the proprietor of a modern-day service station, ready to provide water to keep one’s conveyance running—be it horse or car—and supplies such as spare inner tubes in case of equipment failure. The items at the site relating to tourism all date to after 1890, whereas earlier material, such as tools, horseshoes, horseshoe nails, and buckles, reflects Harrison’s work as a rancher. This matches accounts suggesting that, as he grew older and less physically able, Harrison shifted his energies from tending his flock to entertaining his visitors.

The archaeologists also unearthed a small piece of convex glass with a ridged nickel edge that puzzled them at first, until they realized it was the lens from a Kodak Brownie camera. And, buried under the patio of Harrison’s cabin were a number of extremely deteriorated automobile inner tubes dating to the 1910s. He had apparently stowed supplies that might prove useful for those attempting the challenging drive up the mountain. In a sense, Mallios points out, Harrison was analogous to the proprietor of a modern-day service station, ready to provide water to keep one’s conveyance running—be it horse or car—and supplies such as spare inner tubes in case of equipment failure. The items at the site relating to tourism all date to after 1890, whereas earlier material, such as tools, horseshoes, horseshoe nails, and buckles, reflects Harrison’s work as a rancher. This matches accounts suggesting that, as he grew older and less physically able, Harrison shifted his energies from tending his flock to entertaining his visitors. A range of other artifacts, however, presents an image of Harrison very different from the one known to the public. Most numerous among these are more than 200 fired rifle cartridges discovered in the vicinity of his cabin. This evidence suggests that Harrison not only owned rifles, but also that he was far from shy about firing them in his own backyard. He was never armed when he went to greet visitors, though, and a rifle appears in only one of the 31 known photographs of him. Even in that image, the firearm is off to Harrison’s side, barely visible against a wooden platform. By contrast, white men who settled on the mountain in the years after Harrison arrived invariably had a rifle in hand when they were photographed. Ryan Anderson, an anthropologist at Santa Clara University who has studied how Harrison appears in photographs, suggests that he made an intentional choice in how he presented himself. “He’s not portraying himself as an armed homesteader, and considering the situation, I don’t think that’s accidental,” Anderson says. “If a rumor starts going around that there’s this African American with a bunch of rifles, he probably doesn’t want to draw that kind of attention.” Mallios points out that, according to an 1854 California law that forbade the sale of firearms and ammunition to Native Americans or anyone associated with them, Harrison’s rifles and bullets were likely acquired illegally.

A range of other artifacts, however, presents an image of Harrison very different from the one known to the public. Most numerous among these are more than 200 fired rifle cartridges discovered in the vicinity of his cabin. This evidence suggests that Harrison not only owned rifles, but also that he was far from shy about firing them in his own backyard. He was never armed when he went to greet visitors, though, and a rifle appears in only one of the 31 known photographs of him. Even in that image, the firearm is off to Harrison’s side, barely visible against a wooden platform. By contrast, white men who settled on the mountain in the years after Harrison arrived invariably had a rifle in hand when they were photographed. Ryan Anderson, an anthropologist at Santa Clara University who has studied how Harrison appears in photographs, suggests that he made an intentional choice in how he presented himself. “He’s not portraying himself as an armed homesteader, and considering the situation, I don’t think that’s accidental,” Anderson says. “If a rumor starts going around that there’s this African American with a bunch of rifles, he probably doesn’t want to draw that kind of attention.” Mallios points out that, according to an 1854 California law that forbade the sale of firearms and ammunition to Native Americans or anyone associated with them, Harrison’s rifles and bullets were likely acquired illegally. Yet another potentially hidden facet of Harrison’s story was revealed over a number of years, as the archaeologists recovered a series of implements associated with writing from his cabin: first a sharpened graphite pencil lead, then a pen cap and clip, and finally a number of eraser pieces. This accumulation of evidence hints that Harrison knew how to read and write, despite the fact that throughout his life, he signed many documents with an X, and every census record but one indicates that he was illiterate. The only exception is his final census, in 1920, when he was gravely ill in a hospital in San Diego. Mallios concedes it’s possible Harrison only learned to read and write in the last years of his life, but believes it’s more likely he was only comfortable revealing that he was literate once he had left the mountain. “I was intrigued by the idea that, what if all these years he had kept his literacy a secret and then only on his deathbed in the hospital does he let out that secret,” Mallios says. Like his decision to live on the mountain, Harrison’s motivation to conceal his literacy may have been self-preservation, points out Chuck Ambers, the founder and curator of the African Diaspora Museum and Research Center in San Diego, which was formerly known as the African Museum Casa del Rey Moro. “Reading and writing could be threatening,” says Ambers. “You have certain ex-Confederates in the area and there was always a thing about not teaching African Americans to read and write. I think Harrison hiding that he could read and write was part of his ability to appear nonthreatening.”

Yet another potentially hidden facet of Harrison’s story was revealed over a number of years, as the archaeologists recovered a series of implements associated with writing from his cabin: first a sharpened graphite pencil lead, then a pen cap and clip, and finally a number of eraser pieces. This accumulation of evidence hints that Harrison knew how to read and write, despite the fact that throughout his life, he signed many documents with an X, and every census record but one indicates that he was illiterate. The only exception is his final census, in 1920, when he was gravely ill in a hospital in San Diego. Mallios concedes it’s possible Harrison only learned to read and write in the last years of his life, but believes it’s more likely he was only comfortable revealing that he was literate once he had left the mountain. “I was intrigued by the idea that, what if all these years he had kept his literacy a secret and then only on his deathbed in the hospital does he let out that secret,” Mallios says. Like his decision to live on the mountain, Harrison’s motivation to conceal his literacy may have been self-preservation, points out Chuck Ambers, the founder and curator of the African Diaspora Museum and Research Center in San Diego, which was formerly known as the African Museum Casa del Rey Moro. “Reading and writing could be threatening,” says Ambers. “You have certain ex-Confederates in the area and there was always a thing about not teaching African Americans to read and write. I think Harrison hiding that he could read and write was part of his ability to appear nonthreatening.” The realization that Harrison may have hidden his literacy until the very end of his life was just one of many instances in which Mallios was struck that Harrison had developed a carefully sculpted public persona that obscured or omitted key aspects of his identity. When entertaining travelers, Harrison came across as poorly educated, self-mocking, and folksy. “When I first came here dere was nobody but Injuns,” he would announce, according to tourist Allan Kelly. Harrison would then add, to his audience’s great amusement, “I was de fust white man on dis mountain.” But Mallios found a reference in Robert Asher’s account to a conversation in which Harrison, speaking confidently with no sign of his customary stylized vernacular, explained how to start a fire in damp conditions. “It was as if he had dropped the act,” says Mallios. Reflecting on another lengthy conversation with Harrison, Asher writes, “His language was such as I had been accustomed to all my life, that of a cultivated man.”

The realization that Harrison may have hidden his literacy until the very end of his life was just one of many instances in which Mallios was struck that Harrison had developed a carefully sculpted public persona that obscured or omitted key aspects of his identity. When entertaining travelers, Harrison came across as poorly educated, self-mocking, and folksy. “When I first came here dere was nobody but Injuns,” he would announce, according to tourist Allan Kelly. Harrison would then add, to his audience’s great amusement, “I was de fust white man on dis mountain.” But Mallios found a reference in Robert Asher’s account to a conversation in which Harrison, speaking confidently with no sign of his customary stylized vernacular, explained how to start a fire in damp conditions. “It was as if he had dropped the act,” says Mallios. Reflecting on another lengthy conversation with Harrison, Asher writes, “His language was such as I had been accustomed to all my life, that of a cultivated man.” Again and again, the explanation for these omissions seems to be self-protection. An unarmed, smiling African American man approaching on foot with an afternoon’s worth of tall tales about the backcountry was what people trekked up the mountain to see. A rifle-toting, clear-speaking African American homesteader glowering down from horseback, by contrast, was not. If Harrison were known to have been associated with Native Americans and Catholics at a time when the latter were being persecuted and the former removed from their land in the area, his position would have been even less tenable. “He presented the image he thought people wanted to see,” says Carrico. “You get the impression that he made them laugh and disarmed them, so when they left, they went, ‘That was fun. That was a good trip. He’s quite the guy.’”

Again and again, the explanation for these omissions seems to be self-protection. An unarmed, smiling African American man approaching on foot with an afternoon’s worth of tall tales about the backcountry was what people trekked up the mountain to see. A rifle-toting, clear-speaking African American homesteader glowering down from horseback, by contrast, was not. If Harrison were known to have been associated with Native Americans and Catholics at a time when the latter were being persecuted and the former removed from their land in the area, his position would have been even less tenable. “He presented the image he thought people wanted to see,” says Carrico. “You get the impression that he made them laugh and disarmed them, so when they left, they went, ‘That was fun. That was a good trip. He’s quite the guy.’” As far as anyone knows, Harrison never spoke of his time in slavery to the tourists who visited him or to his neighbors on the mountain, yet Mallios uncovered telling evidence that he carried memories of his origins with him to his California homestead. As the archaeologists excavated the remains of his cabin’s stone foundation, they found that the walls formed a square measuring just 11 feet on each side, an architectural style unknown in the area. Square structures of this size were, however, extremely common among slave quarters in the antebellum South. As at such slave quarters, the overwhelming majority of artifacts uncovered by archaeologists at the site of Harrison’s cabin came from the patio area, whereas the few items found in the cabin itself—including the writing implements, the unused arrow points, and the iron cross—tended to have greater personal importance. While Harrison could have built a much larger rectangular structure similar to those raised by other homesteaders on the mountain, he chose instead to replicate the sort of structure he likely knew as a child. “Maybe he carried with him the idea of what a house should look like, and that’s what he built there,” says Mallios. “But then again, maybe this was just part of his act.”

As far as anyone knows, Harrison never spoke of his time in slavery to the tourists who visited him or to his neighbors on the mountain, yet Mallios uncovered telling evidence that he carried memories of his origins with him to his California homestead. As the archaeologists excavated the remains of his cabin’s stone foundation, they found that the walls formed a square measuring just 11 feet on each side, an architectural style unknown in the area. Square structures of this size were, however, extremely common among slave quarters in the antebellum South. As at such slave quarters, the overwhelming majority of artifacts uncovered by archaeologists at the site of Harrison’s cabin came from the patio area, whereas the few items found in the cabin itself—including the writing implements, the unused arrow points, and the iron cross—tended to have greater personal importance. While Harrison could have built a much larger rectangular structure similar to those raised by other homesteaders on the mountain, he chose instead to replicate the sort of structure he likely knew as a child. “Maybe he carried with him the idea of what a house should look like, and that’s what he built there,” says Mallios. “But then again, maybe this was just part of his act.”