Features

Searching for the Fisher Kings

By JASON URBANUS

Friday, September 17, 2021

In 1895, Frank Hamilton Cushing, a pioneering anthropologist from the Smithsonian Institution, turned his attention to an obscure area of swampland in southwestern Florida. He had been shown a collection of objects that had recently been found by workers extracting peat from a bog on Key Marco, on Florida’s Gulf Coast northwest of the Everglades. Cushing was one of the country’s preeminent scholars of Native American culture, yet the artifacts he saw perplexed him. The finely crafted relics, which he estimated to be quite old, were unlike anything he had seen before. Cushing decided to make the long, arduous trek to Key Marco, where he organized a team to further investigate the site.

In 1895, Frank Hamilton Cushing, a pioneering anthropologist from the Smithsonian Institution, turned his attention to an obscure area of swampland in southwestern Florida. He had been shown a collection of objects that had recently been found by workers extracting peat from a bog on Key Marco, on Florida’s Gulf Coast northwest of the Everglades. Cushing was one of the country’s preeminent scholars of Native American culture, yet the artifacts he saw perplexed him. The finely crafted relics, which he estimated to be quite old, were unlike anything he had seen before. Cushing decided to make the long, arduous trek to Key Marco, where he organized a team to further investigate the site.

Over the next two years, Cushing’s team retrieved thousands of objects that stunned the archaeological community. Preserved in the muddy, oxygen-free conditions of the bog were tools, weapons, ceramics, and household objects made from bone, shell, wood, and woven fibers. There were also painted ceremonial masks and carved animal heads. A six-inch wooden statuette of a feline, known as the Key Marco Cat, is considered by many to be one of the finest pieces of pre-Columbian Native American sculpture.

The people who crafted these objects were a mystery to Cushing and other scholars. Their material culture was seemingly older than and unrelated to that of Native groups living in Florida at the time, such as the Seminole or the Miccosukee. The men and women who had created and used these items had inhabited Florida’s shores long ago. They had, however, left behind evidence of their lives, especially of their mastery of their marine environment. Buried in the muck of Key Marco were fishing nets woven from palm fibers, hammers and other tools made from conch shells, and blades fashioned from shark teeth. Even the land on which they lived owed itself to the sea, as it was formed from heaps of oyster, clam, and conch shells.

Secret Rites of Samothrace

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Monday, September 27, 2021

During the day, the rocky island of Samothrace in the northern Aegean Sea is often veiled by clouds. Wind sweeps across the landscape, and the turbulent waters remain, as they were in antiquity, dangerous for seafarers. When the clouds clear at night, however, the peak of Mount Fengari at the island’s center, which reaches a mile into the sky, becomes visible. From the vantage point of the peak, Homer relates in the Iliad, the sea god Poseidon watched the Trojan War as it unfolded. Nestled in a deep ravine in the mountain’s shadow lie the remains of the Sanctuary of the Theoi Megaloi, or Great Gods. From at least the seventh century B.C., pilgrims walked under the cover of darkness from the nearby ancient city, now known as Palaeopolis, to the sanctuary to be inducted into a secret religious cult. As they passed through an immense marble gateway onto the sanctuary’s eastern hill, they might have heard the rush of water coursing through a channel beneath the entranceway. Amid the sounds of music and chanting emanating from farther within the sanctuary, the prospective initiates reached a sunken circular court. Here, ritual dancing and other performances might have taken place, surrounded by bronze statues that were likely dedicated by previous initiates. The noise and darkness, as well as the use of blindfolds, probably induced an altered state of mind that prepared participants for the forthcoming rituals and sacred revelations. By the flickering light of oil lamps and torches, they began the steep descent down the Sacred Way, to the sanctuary’s heart, to be initiated into the mysteries of the Great Gods.

During the day, the rocky island of Samothrace in the northern Aegean Sea is often veiled by clouds. Wind sweeps across the landscape, and the turbulent waters remain, as they were in antiquity, dangerous for seafarers. When the clouds clear at night, however, the peak of Mount Fengari at the island’s center, which reaches a mile into the sky, becomes visible. From the vantage point of the peak, Homer relates in the Iliad, the sea god Poseidon watched the Trojan War as it unfolded. Nestled in a deep ravine in the mountain’s shadow lie the remains of the Sanctuary of the Theoi Megaloi, or Great Gods. From at least the seventh century B.C., pilgrims walked under the cover of darkness from the nearby ancient city, now known as Palaeopolis, to the sanctuary to be inducted into a secret religious cult. As they passed through an immense marble gateway onto the sanctuary’s eastern hill, they might have heard the rush of water coursing through a channel beneath the entranceway. Amid the sounds of music and chanting emanating from farther within the sanctuary, the prospective initiates reached a sunken circular court. Here, ritual dancing and other performances might have taken place, surrounded by bronze statues that were likely dedicated by previous initiates. The noise and darkness, as well as the use of blindfolds, probably induced an altered state of mind that prepared participants for the forthcoming rituals and sacred revelations. By the flickering light of oil lamps and torches, they began the steep descent down the Sacred Way, to the sanctuary’s heart, to be initiated into the mysteries of the Great Gods.

Because initiates were bound to keep the details of the rites secret, ancient literary sources provide scant details about the cult. Those writers who do discuss the mysteries often give diverging accounts and differing identifications of the gods. Coins dating to the second-century B.C. unearthed at the sanctuary depict a great mother goddess. Some ancient writers associate this goddess with a group of gods called the Kabeiroi. “What we know most clearly about the initiation are its promises and benefits,” says archaeologist Bonna Wescoat of Emory University. “Ancient sources strongly state that the Great Gods are powerful and protective gods. Most say they offer protection at sea, while some say they offer protection in times of need. The benefits they confer could have meant different things to different people, depending on what an initiate most sought from the experience.” Some writers even claim that initiates experienced a moral transformation. According to the first-century B.C. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, initiates into the Samothracian mysteries became “more pious and more just and better in all ways than they had been before.”

Because initiates were bound to keep the details of the rites secret, ancient literary sources provide scant details about the cult. Those writers who do discuss the mysteries often give diverging accounts and differing identifications of the gods. Coins dating to the second-century B.C. unearthed at the sanctuary depict a great mother goddess. Some ancient writers associate this goddess with a group of gods called the Kabeiroi. “What we know most clearly about the initiation are its promises and benefits,” says archaeologist Bonna Wescoat of Emory University. “Ancient sources strongly state that the Great Gods are powerful and protective gods. Most say they offer protection at sea, while some say they offer protection in times of need. The benefits they confer could have meant different things to different people, depending on what an initiate most sought from the experience.” Some writers even claim that initiates experienced a moral transformation. According to the first-century B.C. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus, initiates into the Samothracian mysteries became “more pious and more just and better in all ways than they had been before.”

|

Sidebar:

|

Winged Victory’s Vantage

|

|

Online Exclusive:

|

Inside a Greek Mystery Cult

|

The Pursuit of Wellness

By MARLEY BROWN

Tuesday, August 10, 2021

You may be one of millions of people returning to recently reopened gyms in an attempt to shed a few pounds of pandemic weight. Or, to give yourself a moment of respite between loading the dishwasher and putting the kids to bed, perhaps you have started meditating. Alternatively, you might put on noise-canceling headphones to take in ambient sounds of lakes or jungles through an app on your phone. If so, you are participating in a widespread commitment to wellness, taking part in activities meant to promote and achieve personal well-being.

You may be one of millions of people returning to recently reopened gyms in an attempt to shed a few pounds of pandemic weight. Or, to give yourself a moment of respite between loading the dishwasher and putting the kids to bed, perhaps you have started meditating. Alternatively, you might put on noise-canceling headphones to take in ambient sounds of lakes or jungles through an app on your phone. If so, you are participating in a widespread commitment to wellness, taking part in activities meant to promote and achieve personal well-being.

Peoples of the ancient world practiced self-care, too, with a range of behaviors and rituals that nurtured mind, body, and soul. For instance, around A.D. 60, at Aquae Sulis, the site of natural hot springs in what is now Bath, England, the Romans built a huge temple and spa complex that became a center for both pilgrimage and health. There, Romans and local Britons socialized and bathed, hoping to heal a host of ailments such as rheumatism, arthritis, and gout. They also worshipped the Romano-Celtic healing goddess Sulis Minerva. The Aquae Sulis springs had already been host to centuries—and possibly millennia—of ceremonies held by Bronze and Iron Age communities. Even after the destruction of the Roman baths in the sixth century A.D., Aquae Sulis’ legacy continued. The health-giving properties of the springs were well known in Britain throughout the Middle Ages, and by the seventeenth century, Bath was the place to see and be seen. It became common for visitors to drink the sulfurous thermal waters, a practice known as “taking the cure.” Some still engage in this activity, seeking its purported health benefits.

In fact, many wellness pursuits enjoyed today were developed in the ancient world. There were Egyptian foot massages, Maya communal sweat baths, and expensive Roman face creams. And not only would a group of ancient Indian practitioners of yoga recognize some of your positions, they might even give you a few pointers.

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

The Pursuit of Wellness

Secret Rites of Samothrace

Searching for the Fisher Kings

Letter from Scotland

Digs & Discoveries

Viking Fantasy Island

Kaleidoscopic Walls

For Eternity

Maryland's First Fort

Snake Guide

Man of the Moment

Kiwi Colonists

Leisure Seekers

Neanderthal Hearing

Head of State

A Twisted Hoard

Crowning Glory

Herodian Hangout

Off the Grid

Around the World

Maya city parks, Paleoindian obsidian traders, Çatalhöyük smoke alarm, and a shark attack in Japan

Artifact

Putting a finger on fate

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Cushing named these people the Key Dwellers, but archaeologists now know them as the Calusa, which Spanish sources say meant “fierce people” in their language. Researchers have learned that the Calusa, whose empire and influence spread across a territory from Charlotte Harbor on the Gulf Coast across to the Atlantic Ocean and down to the Florida Keys, were the dominant Native group in southern Florida when Europeans arrived in the sixteenth century. Unlike other complex societies of the Americas, such as the Inca, Aztecs, and Maya, the Calusa eschewed large-scale agriculture, instead building their empire on marine resources. For more than 200 years, they resisted Spanish colonization and Christianization until, ultimately, they disappeared from Florida’s shores.

Cushing named these people the Key Dwellers, but archaeologists now know them as the Calusa, which Spanish sources say meant “fierce people” in their language. Researchers have learned that the Calusa, whose empire and influence spread across a territory from Charlotte Harbor on the Gulf Coast across to the Atlantic Ocean and down to the Florida Keys, were the dominant Native group in southern Florida when Europeans arrived in the sixteenth century. Unlike other complex societies of the Americas, such as the Inca, Aztecs, and Maya, the Calusa eschewed large-scale agriculture, instead building their empire on marine resources. For more than 200 years, they resisted Spanish colonization and Christianization until, ultimately, they disappeared from Florida’s shores. The Calusa themselves did not leave behind any written history. The earliest mention researchers have of their existence comes from sixteenth-century Spanish accounts, especially those of Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda. Escalante Fontaneda was shipwrecked off the Florida coast as a teenager and taken captive by the Calusa, living among them for the next 17 years. From his accounts, it is clear that the Calusa were the most powerful Native group the Spaniards encountered in Florida. Over the course of two centuries, the two nations were by turns enemies and allies. “I would characterize the relationship as mutually beneficial at times,” says Marquardt, “but mostly acrimonious and tense.”

The Calusa themselves did not leave behind any written history. The earliest mention researchers have of their existence comes from sixteenth-century Spanish accounts, especially those of Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda. Escalante Fontaneda was shipwrecked off the Florida coast as a teenager and taken captive by the Calusa, living among them for the next 17 years. From his accounts, it is clear that the Calusa were the most powerful Native group the Spaniards encountered in Florida. Over the course of two centuries, the two nations were by turns enemies and allies. “I would characterize the relationship as mutually beneficial at times,” says Marquardt, “but mostly acrimonious and tense.” Some 40 years later, the Spaniards returned, ushering in their first sustained period of contact with the Calusa. In 1566, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, the first Spanish governor of Florida, arrived at the Calusa capital to hammer out an alliance with their leader, King Caalus. The Calusa needed support from the Spaniards to help ward off threats from their northern rivals, the Tocobaga. The Spanish needed a base in southern Florida from which to expand their burgeoning New World empire. Escalante Fontaneda, who acted as translator, and another Spaniard, named Gonzalo Solís de Merás, later described the meeting, the Calusa settlement, its buildings, and how Menéndez’s retinue of 500 men was met by a crowd of 4,000 Calusa. Caalus is said to have entertained the Spanish governor in a house large enough to hold 2,000 people, where extravagant ceremonies were held as the terms of the treaty were hashed out. This agreement was sealed by the marriage of Caalus’ sister to Menéndez. Until recently, the precise location of this meeting, and of the Calusa capital itself, were unsubstantiated.

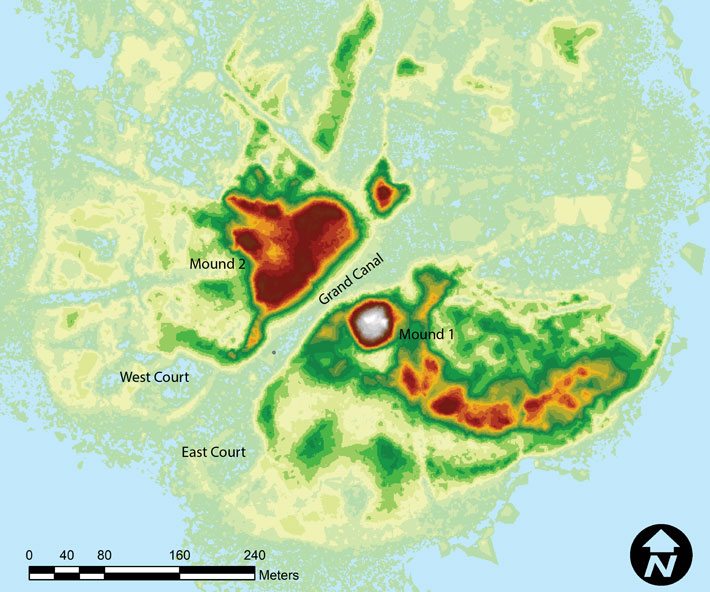

Some 40 years later, the Spaniards returned, ushering in their first sustained period of contact with the Calusa. In 1566, Pedro Menéndez de Avilés, the first Spanish governor of Florida, arrived at the Calusa capital to hammer out an alliance with their leader, King Caalus. The Calusa needed support from the Spaniards to help ward off threats from their northern rivals, the Tocobaga. The Spanish needed a base in southern Florida from which to expand their burgeoning New World empire. Escalante Fontaneda, who acted as translator, and another Spaniard, named Gonzalo Solís de Merás, later described the meeting, the Calusa settlement, its buildings, and how Menéndez’s retinue of 500 men was met by a crowd of 4,000 Calusa. Caalus is said to have entertained the Spanish governor in a house large enough to hold 2,000 people, where extravagant ceremonies were held as the terms of the treaty were hashed out. This agreement was sealed by the marriage of Caalus’ sister to Menéndez. Until recently, the precise location of this meeting, and of the Calusa capital itself, were unsubstantiated. Lidar imaging of Mound Key has revealed that a waterway, known as the Grand Canal, measuring 1,200 feet long and 90 feet wide, was dug through the island, dividing it in half. Several smaller tributary canals branched off, leading to the island’s interior and creating a network of channels perfectly suited for Calusa canoes. At the site of Pineland, the second largest Calusa settlement, 20 miles northwest of Mound Key, the central canal was two and half miles long. Its construction required the removal of more than a million cubic feet of earth. “The Calusa knew the water and were expert hydro-engineers,” says Thompson. “South Florida had a highway system of waterways, be it ones that were natural or human constructed.”

Lidar imaging of Mound Key has revealed that a waterway, known as the Grand Canal, measuring 1,200 feet long and 90 feet wide, was dug through the island, dividing it in half. Several smaller tributary canals branched off, leading to the island’s interior and creating a network of channels perfectly suited for Calusa canoes. At the site of Pineland, the second largest Calusa settlement, 20 miles northwest of Mound Key, the central canal was two and half miles long. Its construction required the removal of more than a million cubic feet of earth. “The Calusa knew the water and were expert hydro-engineers,” says Thompson. “South Florida had a highway system of waterways, be it ones that were natural or human constructed.” Mound Key’s geography, topography, and landscape seemed to Marquardt and Thompson to match the sixteenth-century Spanish maps and records that described the Calusa capital, but definitive archaeological proof remained elusive. Their team needed something conclusive, such as evidence of the famed House of Caalus, which they began searching for in 2013. They believed the most plausible location was atop Mound 1, the island’s highest point. However, the 7,000-square-foot mound was covered in thick vegetation, making extensive archaeological work impossible. The only accessible area was a previously exposed strip of land along the summit’s edge, but this offered an extremely limited view of the mound. “We thought if the house was as big as the sources say it was, it must have taken up the entire summit,” says Thompson, “so the walls have to be close to the edge.” And indeed, they were.

Mound Key’s geography, topography, and landscape seemed to Marquardt and Thompson to match the sixteenth-century Spanish maps and records that described the Calusa capital, but definitive archaeological proof remained elusive. Their team needed something conclusive, such as evidence of the famed House of Caalus, which they began searching for in 2013. They believed the most plausible location was atop Mound 1, the island’s highest point. However, the 7,000-square-foot mound was covered in thick vegetation, making extensive archaeological work impossible. The only accessible area was a previously exposed strip of land along the summit’s edge, but this offered an extremely limited view of the mound. “We thought if the house was as big as the sources say it was, it must have taken up the entire summit,” says Thompson, “so the walls have to be close to the edge.” And indeed, they were. After ground-penetrating radar detected anomalies in the soil, the team began digging and exposed postholes and remnants of an oval building estimated to be around 80 feet long and 65 feet wide, making it one of the largest Native American structures discovered in the Southeast. Radiocarbon dating indicated that the house was first built around A.D. 1000 and was rebuilt and renovated during several phases over the next 500 years. Thompson believes that a structure that large and in such a prominent location must have been the building that the first Spanish visitors describe as being associated with the hereditary Calusa kings. “Our interpretation is that there was a kind of powerful, long-lived lineage associated with the top of that mound,” he says.

After ground-penetrating radar detected anomalies in the soil, the team began digging and exposed postholes and remnants of an oval building estimated to be around 80 feet long and 65 feet wide, making it one of the largest Native American structures discovered in the Southeast. Radiocarbon dating indicated that the house was first built around A.D. 1000 and was rebuilt and renovated during several phases over the next 500 years. Thompson believes that a structure that large and in such a prominent location must have been the building that the first Spanish visitors describe as being associated with the hereditary Calusa kings. “Our interpretation is that there was a kind of powerful, long-lived lineage associated with the top of that mound,” he says. On the eve of the Spaniards’ arrival in America, there may have been 50 to 60 Calusa communities in central and southern Florida with a total population as high as 20,000. During his travels, the Smithsonian’s Cushing estimated that there were several dozen shell mounds lining the coast of southwest Florida. Some of these, such as at Pineland, Josslyn Island, Key Marco, and Mound House have proven to be rich sources of Calusa artifacts. The kingdom was unquestionably ruled by a leader based in Mound Key, whose power, wealth, and prestige were enhanced through tribute paid to him by client communities across Florida. These gifts, which signified allegiance and loyalty to the king, included food, animal hides, mats, and feathers. Paradoxically, the Calusa king’s control over his vast territory was initially strengthened by the arrival of the Spanish in the New World. By the dawn of the sixteenth century, although the Spanish themselves had not yet landed on the peninsula, European goods and gold were already being funneled into Mound Key, sent there by subordinate Native groups along Florida’s southern shores who poached cargo from frequent Spanish shipwrecks. Access to and control of these highly prized European goods further reinforced the Calusa king’s authority.

On the eve of the Spaniards’ arrival in America, there may have been 50 to 60 Calusa communities in central and southern Florida with a total population as high as 20,000. During his travels, the Smithsonian’s Cushing estimated that there were several dozen shell mounds lining the coast of southwest Florida. Some of these, such as at Pineland, Josslyn Island, Key Marco, and Mound House have proven to be rich sources of Calusa artifacts. The kingdom was unquestionably ruled by a leader based in Mound Key, whose power, wealth, and prestige were enhanced through tribute paid to him by client communities across Florida. These gifts, which signified allegiance and loyalty to the king, included food, animal hides, mats, and feathers. Paradoxically, the Calusa king’s control over his vast territory was initially strengthened by the arrival of the Spanish in the New World. By the dawn of the sixteenth century, although the Spanish themselves had not yet landed on the peninsula, European goods and gold were already being funneled into Mound Key, sent there by subordinate Native groups along Florida’s southern shores who poached cargo from frequent Spanish shipwrecks. Access to and control of these highly prized European goods further reinforced the Calusa king’s authority. Archaeologists often refer to this type of society as a complex polity, in which power is wielded by a select number of individuals and families. These elites or nobles have privileges that are denied to others, while the principal leader is responsible for amassing resources, especially food, and redistributing them throughout the community. “Almost all such societies are agricultural,” says Marquardt. Most cultures of this type in the New World relied on surplus production of maize to maintain a stable society. To the surprise of most researchers, the Calusa became the dominant regional power player without large-scale cultivation of maize or any other crop. “They were fishers, not farmers,” Marquardt says, “and the only fishing society to have become a tribute-based kingdom.”

Archaeologists often refer to this type of society as a complex polity, in which power is wielded by a select number of individuals and families. These elites or nobles have privileges that are denied to others, while the principal leader is responsible for amassing resources, especially food, and redistributing them throughout the community. “Almost all such societies are agricultural,” says Marquardt. Most cultures of this type in the New World relied on surplus production of maize to maintain a stable society. To the surprise of most researchers, the Calusa became the dominant regional power player without large-scale cultivation of maize or any other crop. “They were fishers, not farmers,” Marquardt says, “and the only fishing society to have become a tribute-based kingdom.” During the era of European colonization, the Calusa proved themselves worthy adversaries to their would-be Spanish conquerors, safeguarding their independence longer than any other Indigenous Floridians. “The Calusa maintained their society and their cultural traditions for nearly 200 years following European contact, far longer than many other societies in the eastern United States,” says Marquardt. They endured despite the rapid collapse of the treaty forged between Menéndez and Caalus on Mound Key. The king became enraged that the Spanish were not upholding their end of the deal to aid him in his conflict against the Tocobaga and began plotting against his European guests. Caalus was betrayed and assassinated in 1567. His cousin and successor, Felipe, who conspired in Caalus’ downfall, initially maintained an alliance with the Spanish, but also eventually turned against them and attacked a Spanish supply ship. He, too, was executed, in 1569. The Calusa burned their settlement at Mound Key and abandoned the island. They returned soon thereafter and remained politically dominant in southern Florida for another 100 years, but the Spanish had had enough. The Jesuit mission and fort at San Antón de Carlos were abandoned.

During the era of European colonization, the Calusa proved themselves worthy adversaries to their would-be Spanish conquerors, safeguarding their independence longer than any other Indigenous Floridians. “The Calusa maintained their society and their cultural traditions for nearly 200 years following European contact, far longer than many other societies in the eastern United States,” says Marquardt. They endured despite the rapid collapse of the treaty forged between Menéndez and Caalus on Mound Key. The king became enraged that the Spanish were not upholding their end of the deal to aid him in his conflict against the Tocobaga and began plotting against his European guests. Caalus was betrayed and assassinated in 1567. His cousin and successor, Felipe, who conspired in Caalus’ downfall, initially maintained an alliance with the Spanish, but also eventually turned against them and attacked a Spanish supply ship. He, too, was executed, in 1569. The Calusa burned their settlement at Mound Key and abandoned the island. They returned soon thereafter and remained politically dominant in southern Florida for another 100 years, but the Spanish had had enough. The Jesuit mission and fort at San Antón de Carlos were abandoned. Despite Samothrace’s remote location, the mystery cult of the Great Gods was well known in the ancient world, second in popularity to the mysteries celebrated at Eleusis, outside Athens. Pilgrims traveled by ship from across Greece, the Black Sea region, Asia Minor, and Rome for initiation, which was offered whenever a sufficient number of participants arrived on the island during the sailing season, from April through October.

Despite Samothrace’s remote location, the mystery cult of the Great Gods was well known in the ancient world, second in popularity to the mysteries celebrated at Eleusis, outside Athens. Pilgrims traveled by ship from across Greece, the Black Sea region, Asia Minor, and Rome for initiation, which was offered whenever a sufficient number of participants arrived on the island during the sailing season, from April through October. Over the past decade, an interdisciplinary team led by Wescoat, who has directed the American excavations since 2012 with the cooperation of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Evros, has turned its attention back to the western hill. By considering the interaction between the natural landscape and built environment, examining small votive objects and other items initiates left behind, and through survey, excavation, archival research, and 3-D modeling, the archaeologists have begun to re-create the sensory, spiritual, and emotional experience of initiates as they were introduced to the rites of the Great Gods. “We want to explore the landscape, the connectedness of monuments, ancient initiates’ route through the sacred spaces, and the issues of what they could and could not see,” Wescoat says. “These aren’t questions that have been asked in the past.”

Over the past decade, an interdisciplinary team led by Wescoat, who has directed the American excavations since 2012 with the cooperation of the Ephorate of Antiquities of Evros, has turned its attention back to the western hill. By considering the interaction between the natural landscape and built environment, examining small votive objects and other items initiates left behind, and through survey, excavation, archival research, and 3-D modeling, the archaeologists have begun to re-create the sensory, spiritual, and emotional experience of initiates as they were introduced to the rites of the Great Gods. “We want to explore the landscape, the connectedness of monuments, ancient initiates’ route through the sacred spaces, and the issues of what they could and could not see,” Wescoat says. “These aren’t questions that have been asked in the past.” By the mid-fourth century B.C., a few modest buildings had sprung up on the sanctuary’s eastern hill and in its central valley. Around this time, the Macedonian king Philip II (r. 359–336 B.C.) and his future wife Olympias, the parents of Alexander the Great, met on the island to negotiate their marriage and to be initiated into the cult. Their presence on Samothrace seems to have spurred elite patrons to invest in the sanctuary on an unprecedented level, beginning with the construction of a monumental marble building in the middle of the central valley around 340 B.C. This structure is now called the Hall of Choral Dancers after a frieze depicting more than 900 dancing young women that once wrapped around its exterior. The hall is the sanctuary’s oldest standing cult building and incorporated remnants of an earlier chamber into its core. Wescoat believes it may have been commissioned by Philip himself. “There was no gradual lead-up to this, just small buildings made of local materials and then—boom—this extraordinary structure built of imported marble,” she says. “It’s hard for me to see it as a project the Samothracians could have pulled off on their own.”

By the mid-fourth century B.C., a few modest buildings had sprung up on the sanctuary’s eastern hill and in its central valley. Around this time, the Macedonian king Philip II (r. 359–336 B.C.) and his future wife Olympias, the parents of Alexander the Great, met on the island to negotiate their marriage and to be initiated into the cult. Their presence on Samothrace seems to have spurred elite patrons to invest in the sanctuary on an unprecedented level, beginning with the construction of a monumental marble building in the middle of the central valley around 340 B.C. This structure is now called the Hall of Choral Dancers after a frieze depicting more than 900 dancing young women that once wrapped around its exterior. The hall is the sanctuary’s oldest standing cult building and incorporated remnants of an earlier chamber into its core. Wescoat believes it may have been commissioned by Philip himself. “There was no gradual lead-up to this, just small buildings made of local materials and then—boom—this extraordinary structure built of imported marble,” she says. “It’s hard for me to see it as a project the Samothracians could have pulled off on their own.” Over the next century, the Sanctuary of the Great Gods became an increasingly popular destination filled with grand monuments. These were funded by Macedonian royals including the Ptolemies, a dynasty that ruled Egypt from 304 to 30 B.C. Alexander’s successors, his half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus and son Alexander IV, dedicated a marble building fronted by Doric columns during their short joint reign (322–317 B.C.). Ptolemy II Philadelphus (r. 284–246 B.C.) built the gateway that served as the sanctuary’s entrance. Opposite the Hall of Choral Dancers, Ptolemy’s wife Arsinoe II commissioned a rotunda that was the largest circular building in the Hellenistic world. “All these monuments transformed the sanctuary into an international center and a glittering display of power and opulence,” Wescoat says.

Over the next century, the Sanctuary of the Great Gods became an increasingly popular destination filled with grand monuments. These were funded by Macedonian royals including the Ptolemies, a dynasty that ruled Egypt from 304 to 30 B.C. Alexander’s successors, his half-brother Philip III Arrhidaeus and son Alexander IV, dedicated a marble building fronted by Doric columns during their short joint reign (322–317 B.C.). Ptolemy II Philadelphus (r. 284–246 B.C.) built the gateway that served as the sanctuary’s entrance. Opposite the Hall of Choral Dancers, Ptolemy’s wife Arsinoe II commissioned a rotunda that was the largest circular building in the Hellenistic world. “All these monuments transformed the sanctuary into an international center and a glittering display of power and opulence,” Wescoat says. The nocturnal timing of the initiation rites certainly would have heightened the drama of the natural setting. Moonlight and artificial light from torches would have only partially illuminated sculptures on facades and ornate coffered ceilings. “Throughout the sanctuary’s history, designers, architects, and patrons built monuments in a way that harnessed natural features of the landscape to increase the impressiveness and the affective, emotional power of the site,” says archaeologist Maggie Popkin of Case Western Reserve University. Disorientation caused by the sanctuary’s labyrinthine design might have evoked a range of emotions that are echoed in the few ancient accounts of the secret rites. Several sources mention the myth of the abduction of Harmonia, daughter of Zeus and Electra, by the hero Kadmos. According to the myth, Kadmos was one of the first people from outside Samothrace to be initiated, and while on the island, he whisked Harmonia from her home to the city of Thebes. Some versions of the myth also include a joyous wedding between Kadmos and Harmonia. “There was this emotional push and pull of loss and recovery, of terror and celebration,” Wescoat says.

The nocturnal timing of the initiation rites certainly would have heightened the drama of the natural setting. Moonlight and artificial light from torches would have only partially illuminated sculptures on facades and ornate coffered ceilings. “Throughout the sanctuary’s history, designers, architects, and patrons built monuments in a way that harnessed natural features of the landscape to increase the impressiveness and the affective, emotional power of the site,” says archaeologist Maggie Popkin of Case Western Reserve University. Disorientation caused by the sanctuary’s labyrinthine design might have evoked a range of emotions that are echoed in the few ancient accounts of the secret rites. Several sources mention the myth of the abduction of Harmonia, daughter of Zeus and Electra, by the hero Kadmos. According to the myth, Kadmos was one of the first people from outside Samothrace to be initiated, and while on the island, he whisked Harmonia from her home to the city of Thebes. Some versions of the myth also include a joyous wedding between Kadmos and Harmonia. “There was this emotional push and pull of loss and recovery, of terror and celebration,” Wescoat says. The sanctuary’s design placed visitors in front of important buildings, but only allowed them to see the structures’ facades from particular angles. “The buildings would be revealed to viewers in a very specific way that gave them the full intended effect of the architecture,” Popkin says. For example, at the bottom of the Sacred Way, initiates would have approached the Hall of Choral Dancers from the side, not from its imposing front. They would have had to round the corner of the hall to see the sculptures that adorned its facade. Some ritual activity occurred inside the building as well, though it’s not clear to what extent initiates were involved. Inside the building’s two large chambers, archaeologists have uncovered bothroi, or ritual channels for pouring libations into the earth, and traces of small hearths. “This was probably the most important cult building,” Wescoat says. “Whether all initiation happened in it, and how it was designed to accommodate that, is a matter of great debate among scholars, including many of our team members.”

The sanctuary’s design placed visitors in front of important buildings, but only allowed them to see the structures’ facades from particular angles. “The buildings would be revealed to viewers in a very specific way that gave them the full intended effect of the architecture,” Popkin says. For example, at the bottom of the Sacred Way, initiates would have approached the Hall of Choral Dancers from the side, not from its imposing front. They would have had to round the corner of the hall to see the sculptures that adorned its facade. Some ritual activity occurred inside the building as well, though it’s not clear to what extent initiates were involved. Inside the building’s two large chambers, archaeologists have uncovered bothroi, or ritual channels for pouring libations into the earth, and traces of small hearths. “This was probably the most important cult building,” Wescoat says. “Whether all initiation happened in it, and how it was designed to accommodate that, is a matter of great debate among scholars, including many of our team members.” Beyond the open space in front of the facade of the Hall of Choral Dancers, the prescribed route becomes unclear. It seems that visitors could go in a few different directions. Digital modelers are exploring potential pathways through the sanctuary using gaming software and agent-based modeling, which simulates the movements of groups of people who are given a degree of autonomy to make collective decisions. Even with the potential for more freedom of movement, the central valley’s topography nevertheless structured initiates’ pathways. Today, as millennia ago, a natural torrent runs south to north through the length of the sanctuary and out to sea. Past excavators largely viewed this water channel as a nuisance, but in recent years the team has reconsidered it as a kind of monument in itself that may have played an integral role in initiation. In 2019, they excavated along the torrent and documented the ancient course of its channel, which was at least 13 feet deep and 13 feet wide at its broadest point. It is unlikely that the channel was covered, says archaeologist Andrew Farinholt Ward of Indiana University, and though little evidence of bridges survives, there were crossings at a few key points. Initiates would have had to cross over the torrent at least twice to access the southern area of the sanctuary and the theater. “They would have looked down into the channel that, at certain times of year, was rushing with water,” Ward says. “They might have been terrified, the power of the water eliciting a ritual fear that the Greeks liked to have in their sanctuaries. I think part of the reason why they left the ravines open and visible is that even when the torrent wasn’t rushing through, visitors would have still been reminded of that potential.”

Beyond the open space in front of the facade of the Hall of Choral Dancers, the prescribed route becomes unclear. It seems that visitors could go in a few different directions. Digital modelers are exploring potential pathways through the sanctuary using gaming software and agent-based modeling, which simulates the movements of groups of people who are given a degree of autonomy to make collective decisions. Even with the potential for more freedom of movement, the central valley’s topography nevertheless structured initiates’ pathways. Today, as millennia ago, a natural torrent runs south to north through the length of the sanctuary and out to sea. Past excavators largely viewed this water channel as a nuisance, but in recent years the team has reconsidered it as a kind of monument in itself that may have played an integral role in initiation. In 2019, they excavated along the torrent and documented the ancient course of its channel, which was at least 13 feet deep and 13 feet wide at its broadest point. It is unlikely that the channel was covered, says archaeologist Andrew Farinholt Ward of Indiana University, and though little evidence of bridges survives, there were crossings at a few key points. Initiates would have had to cross over the torrent at least twice to access the southern area of the sanctuary and the theater. “They would have looked down into the channel that, at certain times of year, was rushing with water,” Ward says. “They might have been terrified, the power of the water eliciting a ritual fear that the Greeks liked to have in their sanctuaries. I think part of the reason why they left the ravines open and visible is that even when the torrent wasn’t rushing through, visitors would have still been reminded of that potential.” As the international popularity of the cult of the Great Gods grew, beginning in the fourth century B.C., the enterprising Samothracians continued to invest in new monuments on the western hill in order to promote their sanctuary. During excavations in 2018, the team rediscovered the theater and surviving remnants of what project geologists have identified as locally quarried white limestone and the vibrant purple stone called porphyritic rhyolite that was used for the theater’s seating. They estimate the theater could hold up to 1,500 spectators, who perhaps also visited the sanctuary for Samothrace’s annual festival. Currently, the theater’s steps are the only known ancient path to the Nike monument and the 340-foot-long stoa, or walled portico, the sanctuary’s largest building. “The stoa was one of the main social spaces in the sanctuary,” Holzman says. “It’s the only place that could have accommodated the kinds of crowds that would have gathered to use the theater.”

As the international popularity of the cult of the Great Gods grew, beginning in the fourth century B.C., the enterprising Samothracians continued to invest in new monuments on the western hill in order to promote their sanctuary. During excavations in 2018, the team rediscovered the theater and surviving remnants of what project geologists have identified as locally quarried white limestone and the vibrant purple stone called porphyritic rhyolite that was used for the theater’s seating. They estimate the theater could hold up to 1,500 spectators, who perhaps also visited the sanctuary for Samothrace’s annual festival. Currently, the theater’s steps are the only known ancient path to the Nike monument and the 340-foot-long stoa, or walled portico, the sanctuary’s largest building. “The stoa was one of the main social spaces in the sanctuary,” Holzman says. “It’s the only place that could have accommodated the kinds of crowds that would have gathered to use the theater.”

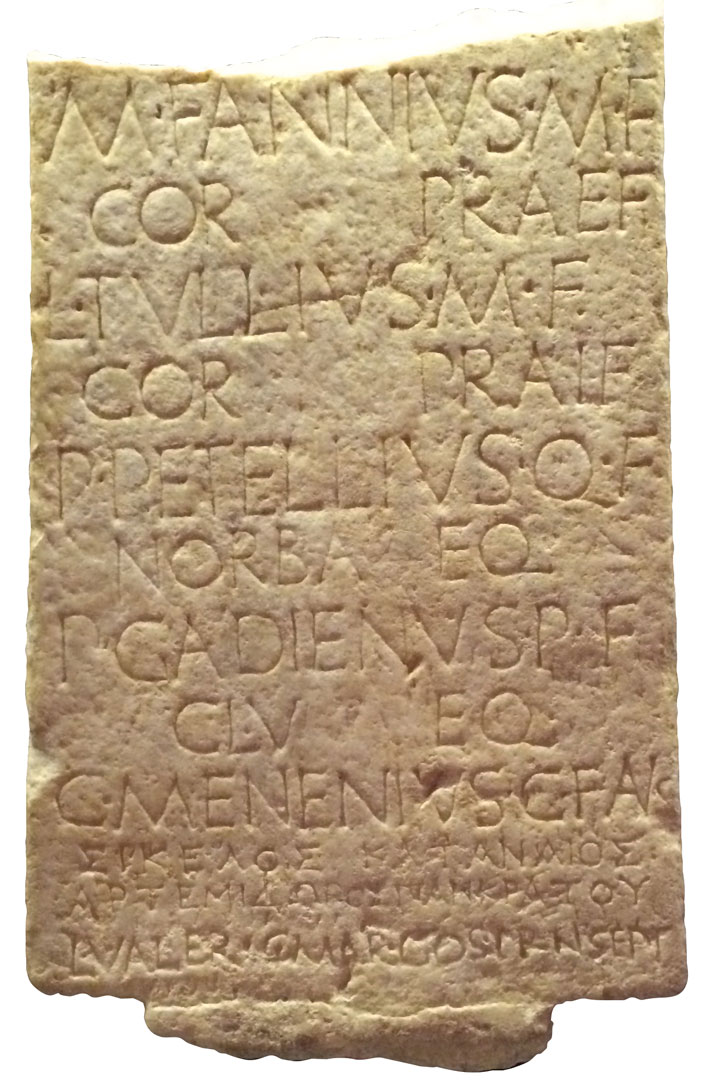

The western hill was another venue where elite patrons flaunted their wealth and influence by constructing monuments, many of which highlighted the role of the Great Gods as protectors of seafarers. These include the Nike monument and the neorion, a building that housed a massive ship elevated on marble supports. Higher up the hill, along the stoa’s facade, gleaming columns topped with bronze statues competed with other gilt-bronze sculptures for visitors’ attention. Artifacts excavated from the stoa’s foundations and interior hint at the identities of Samothrace’s humbler initiates. Bronze fishhooks recovered from the building were left as votive offerings to the gods in thanks for a safe sea passage, along with terracotta statues, hairpins, and jewelry. There were also magnetized iron rings, which, according to several ancient sources, were given to pilgrims as tokens of their initiation. “One of the appeals of coming to Samothrace and participating in its rituals was membership in a club of Samothracian initiates,” Holzman says. Fragments of plaster unearthed in the 1960s that once adorned the walls of the stoa bear graffiti recording the names of initiates. This imitated the practice of carving names in stone. “Clearly, writing your name down as an initiate was an important element of this,” Holzman adds. The bonds formed on Samothrace endured even after initiates left the island. Throughout the Greek world, people built modest shrines as well as larger religious complexes where they met to share fellowship and worship the Samothracian gods.

The western hill was another venue where elite patrons flaunted their wealth and influence by constructing monuments, many of which highlighted the role of the Great Gods as protectors of seafarers. These include the Nike monument and the neorion, a building that housed a massive ship elevated on marble supports. Higher up the hill, along the stoa’s facade, gleaming columns topped with bronze statues competed with other gilt-bronze sculptures for visitors’ attention. Artifacts excavated from the stoa’s foundations and interior hint at the identities of Samothrace’s humbler initiates. Bronze fishhooks recovered from the building were left as votive offerings to the gods in thanks for a safe sea passage, along with terracotta statues, hairpins, and jewelry. There were also magnetized iron rings, which, according to several ancient sources, were given to pilgrims as tokens of their initiation. “One of the appeals of coming to Samothrace and participating in its rituals was membership in a club of Samothracian initiates,” Holzman says. Fragments of plaster unearthed in the 1960s that once adorned the walls of the stoa bear graffiti recording the names of initiates. This imitated the practice of carving names in stone. “Clearly, writing your name down as an initiate was an important element of this,” Holzman adds. The bonds formed on Samothrace endured even after initiates left the island. Throughout the Greek world, people built modest shrines as well as larger religious complexes where they met to share fellowship and worship the Samothracian gods. The Samothracians and international patrons continued to build and remodel structures throughout the sanctuary for nearly 500 years. At the beginning of the first century A.D., an earthquake necessitated repairs to Arsinoe II’s rotunda and the Hieron. A disastrous event in the early second century A.D., probably another earthquake, razed the monuments of the eastern hill and damaged the walled structure around the Nike statue. Although they repaired the Nike monument, the Samothracians didn’t rebuild on the eastern hill. The final securely dated initiate list was inscribed later that century, and finds such as lamps, coins, and glass suggest that activity continued into the third and perhaps fourth centuries A.D. But it’s unclear when exactly cult rituals at the site ceased. As the Great Gods’ significance waned, Wescoat believes, people stopped coming and the cult gradually died out.

The Samothracians and international patrons continued to build and remodel structures throughout the sanctuary for nearly 500 years. At the beginning of the first century A.D., an earthquake necessitated repairs to Arsinoe II’s rotunda and the Hieron. A disastrous event in the early second century A.D., probably another earthquake, razed the monuments of the eastern hill and damaged the walled structure around the Nike statue. Although they repaired the Nike monument, the Samothracians didn’t rebuild on the eastern hill. The final securely dated initiate list was inscribed later that century, and finds such as lamps, coins, and glass suggest that activity continued into the third and perhaps fourth centuries A.D. But it’s unclear when exactly cult rituals at the site ceased. As the Great Gods’ significance waned, Wescoat believes, people stopped coming and the cult gradually died out.