Wellness

Community

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, August 10, 2021

For many of the some six million Maya people living in Central America today, the temazcal, or sweat lodge, is an important feature of their daily lives. Temazcals are small earthen, stone, or brush structures that function as family saunas where water is poured over fires to generate steam that aids in cleansing the body. Such sweat lodges date back to at least the Classic period (A.D. 250–900). Before the arrival of the Spanish, public temazcals were constructed throughout Maya cities and villages where they likely served a wide range of purposes. University of Colorado Boulder archaeologist Payson Sheets notes that temazcals were used in activities and rituals surrounding childbirth, as they still are. Some ancient stone examples were located near ball courts, and may have had a connection to the Maya ball game.

For many of the some six million Maya people living in Central America today, the temazcal, or sweat lodge, is an important feature of their daily lives. Temazcals are small earthen, stone, or brush structures that function as family saunas where water is poured over fires to generate steam that aids in cleansing the body. Such sweat lodges date back to at least the Classic period (A.D. 250–900). Before the arrival of the Spanish, public temazcals were constructed throughout Maya cities and villages where they likely served a wide range of purposes. University of Colorado Boulder archaeologist Payson Sheets notes that temazcals were used in activities and rituals surrounding childbirth, as they still are. Some ancient stone examples were located near ball courts, and may have had a connection to the Maya ball game.

A recent study conducted by Sheets and his colleagues hints at another role sweat lodges could have played in Maya communities. They studied a faithful reconstruction of a three-foot-tall domed temazcal that was unearthed at the village of Cerén in El Salvador, which was preserved by a volcanic eruption around A.D. 600. Visitors to the reconstructed temazcal, which can seat about 12 people, noticed that their voices were significantly altered when they went inside. When Sheets measured and compared the tone of his voice inside and outside the temazcal, he found its domed ceiling lowered his voice to 64 hertz, an extremely low tone that even bass singers struggle to achieve. Sheets speculates that this sweat lodge was designed to dramatically lower the voices of diviners who chanted during activities such as initiation rituals. “That chanting would have sounded like words spoken by a spirit or deity,” says Sheets. “The power of that would have been just tremendous.” In addition to serving as a public sauna, the temazcal at Cerén could also have functioned as a place of profound communal religious experiences that were key to the collective well-being of the village.

Exercise

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Tuesday, August 10, 2021

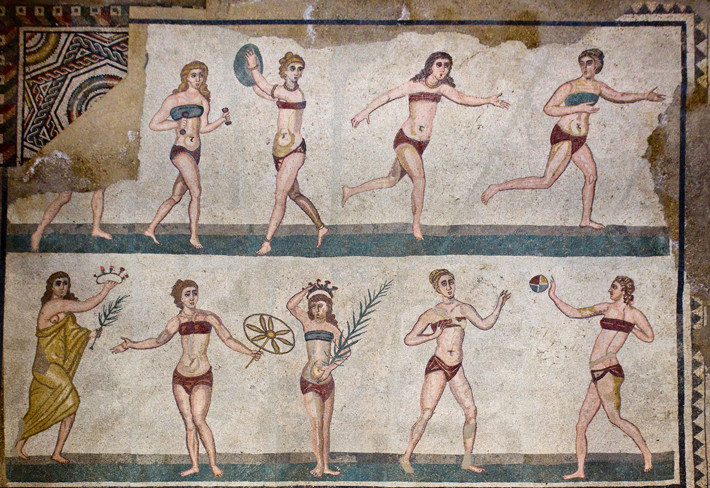

One of antiquity’s most prolific writers on the subject of health and wellness was the second-century A.D. physician, surgeon, and philosopher Galen. He saw health not just as lack of disease, but as a state that could be achieved by living a balanced life, an important component of which was moderate exercise. For the ancient Greeks, exercise meant competition, often in organized festivals such as the Olympics—the word “athlete” comes from the ancient Greek athlos, meaning contest. Participation in these events was limited to young men of certain classes. Exercise was also a crucial part of preparation for Greek military service, and thus women were excluded. But in the Roman world, exercise was more universally popular, and both men and women were frequent participants. Romans often exercised at the public baths, where both sexes and most social classes regularly gathered, says classicist Nigel Crowther of Western University. Men might play ball, run, wrestle, box, or lift weights. Women swam, played a hoop-rolling game called trochus, and especially favored ball games. “Galen suggests that ball games were good training for the fitness of both body and mind,” Crowther says.

One of antiquity’s most prolific writers on the subject of health and wellness was the second-century A.D. physician, surgeon, and philosopher Galen. He saw health not just as lack of disease, but as a state that could be achieved by living a balanced life, an important component of which was moderate exercise. For the ancient Greeks, exercise meant competition, often in organized festivals such as the Olympics—the word “athlete” comes from the ancient Greek athlos, meaning contest. Participation in these events was limited to young men of certain classes. Exercise was also a crucial part of preparation for Greek military service, and thus women were excluded. But in the Roman world, exercise was more universally popular, and both men and women were frequent participants. Romans often exercised at the public baths, where both sexes and most social classes regularly gathered, says classicist Nigel Crowther of Western University. Men might play ball, run, wrestle, box, or lift weights. Women swam, played a hoop-rolling game called trochus, and especially favored ball games. “Galen suggests that ball games were good training for the fitness of both body and mind,” Crowther says.

Self-Care

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, August 10, 2021

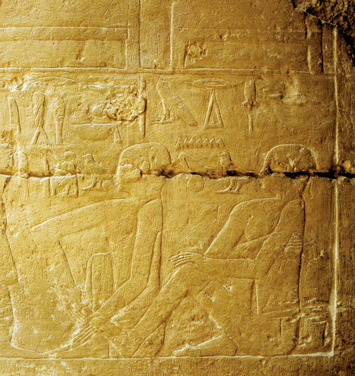

In ancient Egypt, well-being was tied to good hygiene and personal beauty, which were central to the identity of mighty pharaohs and low-ranking commoners alike. Minia University Egyptologist Engy El-Kilany argues that one preoccupation of ancient Egyptians was the beautification and rejuvenation of weary feet. She points to the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.) Papyrus of Kahun, which describes foot massage as treatment for a woman who had aching legs and calves after a long walk. El-Kilany has also cataloged representations of foot washing, foot massage, and pedicures in ancient Egyptian tomb paintings. These include depictions of pedicures in the tomb of two 5th Dynasty (ca. 2465–2323 B.C.) officials at Saqqara who held the title “manicurist of the king.” Reliefs at another tomb at Saqqara, that of the 6th Dynasty (ca. 2323–2150 B.C.) physician Ankhmahor, show masseurs attending to their clients’ feet. El-Kilany believes some of these images may depict not just foot massage, but a form of reflexology. This alternative therapy involves applying pressure to different areas of the feet and hands to alleviate pain in corresponding zones of the body. If the practice depicted in Ankhmahor’s tomb was indeed reflexology, it would further demonstrate that ancient Egyptians took their foot care seriously. “Taking care of the body has always been a common human practice,” says El-Kilany. “It motivated people towards perfection in every single detail in their life.”

In ancient Egypt, well-being was tied to good hygiene and personal beauty, which were central to the identity of mighty pharaohs and low-ranking commoners alike. Minia University Egyptologist Engy El-Kilany argues that one preoccupation of ancient Egyptians was the beautification and rejuvenation of weary feet. She points to the Middle Kingdom (ca. 2030–1640 B.C.) Papyrus of Kahun, which describes foot massage as treatment for a woman who had aching legs and calves after a long walk. El-Kilany has also cataloged representations of foot washing, foot massage, and pedicures in ancient Egyptian tomb paintings. These include depictions of pedicures in the tomb of two 5th Dynasty (ca. 2465–2323 B.C.) officials at Saqqara who held the title “manicurist of the king.” Reliefs at another tomb at Saqqara, that of the 6th Dynasty (ca. 2323–2150 B.C.) physician Ankhmahor, show masseurs attending to their clients’ feet. El-Kilany believes some of these images may depict not just foot massage, but a form of reflexology. This alternative therapy involves applying pressure to different areas of the feet and hands to alleviate pain in corresponding zones of the body. If the practice depicted in Ankhmahor’s tomb was indeed reflexology, it would further demonstrate that ancient Egyptians took their foot care seriously. “Taking care of the body has always been a common human practice,” says El-Kilany. “It motivated people towards perfection in every single detail in their life.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement