Digs & Discoveries

Maryland's First Fort

By JASON URBANUS

Tuesday, August 10, 2021

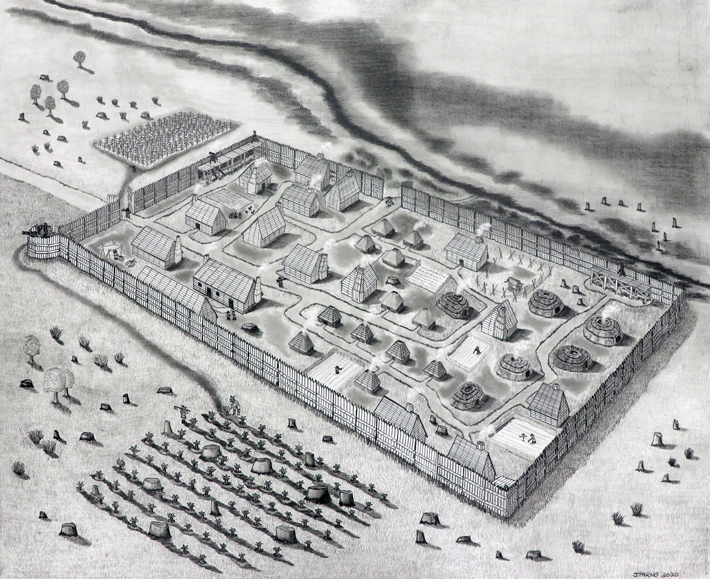

The decades-long search for a colonial-era fort in southeastern Maryland ended when archaeologists confirmed its location outside Historic St. Mary’s City. St. Mary’s Fort was built in 1634 by Maryland’s first European settlers, who purchased a plot of land from the local Yaocomaco people. The settlement was the fourth English colony in America, following only Jamestown, Plymouth, and the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It became Maryland’s first capital.

The decades-long search for a colonial-era fort in southeastern Maryland ended when archaeologists confirmed its location outside Historic St. Mary’s City. St. Mary’s Fort was built in 1634 by Maryland’s first European settlers, who purchased a plot of land from the local Yaocomaco people. The settlement was the fourth English colony in America, following only Jamestown, Plymouth, and the Massachusetts Bay Colony. It became Maryland’s first capital.

Seventeenth-century documents include a vague description of the fort’s dimensions and location, but archaeological work over the past 50 years had failed to uncover proof of its existence. Locating the fort was challenging because it was only occupied intensively for six to eight years, says Travis Parno, director of research and collections for Historic St. Mary’s City. Thus, there were fewer artifacts to be found than at other sites occupied for multiple generations.

According to tradition, the fort was located along the banks of the St. Mary’s River. But recent geophysical surveys in a field more than 1,000 feet from the river detected traces of a large rectangular palisade enclosing a space roughly the size of a football field. Subsequent investigations revealed postholes, hearths, the footprints of buildings, and seventeenth-century cultural material that helped verify that this was the elusive fort. These included a 1633/1634 King Charles silver shilling and a 1622 copper five-saints medallion.

According to tradition, the fort was located along the banks of the St. Mary’s River. But recent geophysical surveys in a field more than 1,000 feet from the river detected traces of a large rectangular palisade enclosing a space roughly the size of a football field. Subsequent investigations revealed postholes, hearths, the footprints of buildings, and seventeenth-century cultural material that helped verify that this was the elusive fort. These included a 1633/1634 King Charles silver shilling and a 1622 copper five-saints medallion.

For Eternity

By DANIEL WEISS

Tuesday, August 10, 2021

The remains of a man and woman who were buried in a loving embrace have been unearthed from a cemetery in northern China’s Shanxi Province. The burial dates to the Northern Wei Dynasty (A.D. 386–534) and is the first tomb with a couple embracing to have been discovered in China. According to Qian Wang, an anthropologist at Texas A&M University’s College of Dentistry, the man likely died first and the woman, who was buried wearing a ring on her left ring finger, then sacrificed herself so that they might be interred together. Wang notes that, at the time, the practice of committing suicide for love was featured in a number of popular stories.

The remains of a man and woman who were buried in a loving embrace have been unearthed from a cemetery in northern China’s Shanxi Province. The burial dates to the Northern Wei Dynasty (A.D. 386–534) and is the first tomb with a couple embracing to have been discovered in China. According to Qian Wang, an anthropologist at Texas A&M University’s College of Dentistry, the man likely died first and the woman, who was buried wearing a ring on her left ring finger, then sacrificed herself so that they might be interred together. Wang notes that, at the time, the practice of committing suicide for love was featured in a number of popular stories.

Viking Fantasy Island

By DANIEL WEISS

Tuesday, August 10, 2021

On the southern coast of the small Danish island of Hjarnø, just east of the mainland, lies a curious collection of stones arranged to form the outlines of boats. More than 1,000 such monuments, called ship settings, which often include burials, have been found throughout the Baltic region. Some of the oldest examples, dating to as early as 1300 B.C., are located in southern Sweden. Based on grave goods uncovered in a 1936 excavation, the Hjarnø ship settings are believed to date to the late Iron Age (A.D. 600–800) or Viking Age (A.D. 800–1000). The tradition, which had faded, was revived during this period, says Erin Sebo, a medievalist at Flinders University who led a survey of the Hjarnø settings in 2018.

On the southern coast of the small Danish island of Hjarnø, just east of the mainland, lies a curious collection of stones arranged to form the outlines of boats. More than 1,000 such monuments, called ship settings, which often include burials, have been found throughout the Baltic region. Some of the oldest examples, dating to as early as 1300 B.C., are located in southern Sweden. Based on grave goods uncovered in a 1936 excavation, the Hjarnø ship settings are believed to date to the late Iron Age (A.D. 600–800) or Viking Age (A.D. 800–1000). The tradition, which had faded, was revived during this period, says Erin Sebo, a medievalist at Flinders University who led a survey of the Hjarnø settings in 2018.

At first glance, these settings, known as the Kalvestene, or “calf stones”—because they are located on a stretch of land fit only for grazing livestock—seem unremarkable. The 10 ship shapes are neither particularly numerous nor big. Each measures around six feet long, with one exception that is 40 feet long. Yet, for reasons that have never been fully understood, the Kalvestene attained a surprising level of renown in medieval Scandinavia. The earliest surviving mention of the ship settings comes from Saxo Grammaticus, a twelfth-century Danish theologian based in Lund, which is now in southern Sweden. Saxo identifies the Kalvestene as the burial place of a legendary king named Hiarni, a peasant who was crowned after writing a great poem upon the death of Frothi, the previous king. After Hiarni was slain by Frothi’s son, Saxo writes, he was buried in a barrow, or mound, on Hjarnø.

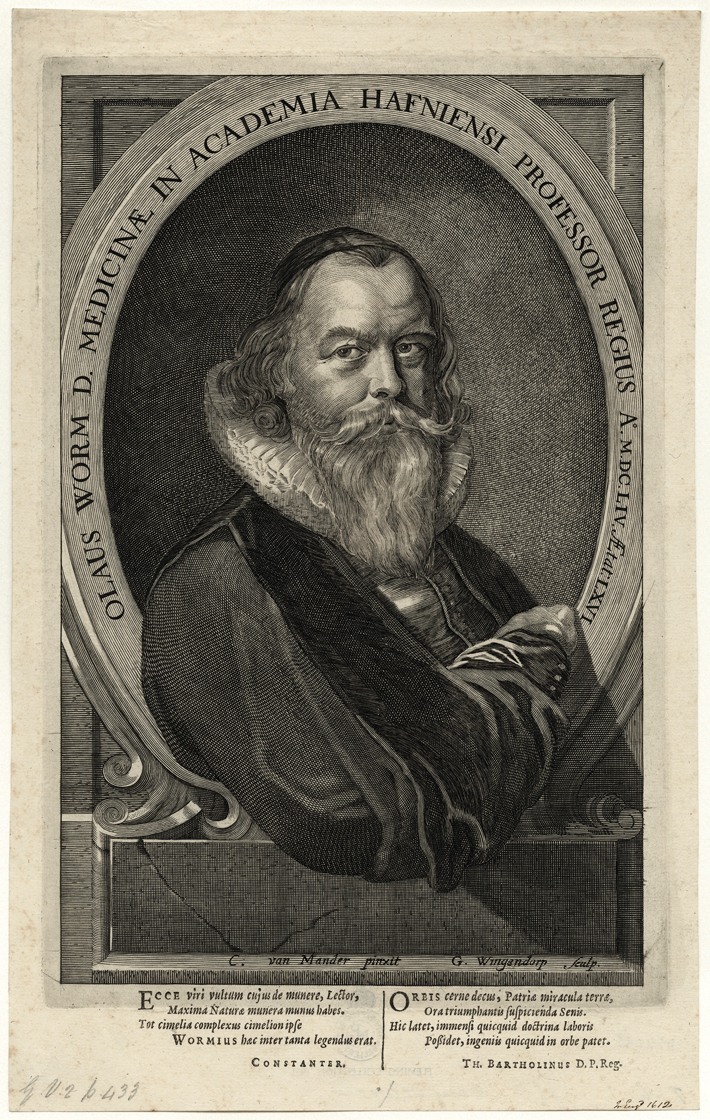

Saxo likely never saw the Kalvestene, says Sebo, as no evidence exists that there was ever a barrow there. Still, his account was frequently repeated over the centuries. Among those to spread the tale was a professor and antiquarian at the University of Copenhagen named Ole Worm, who published a description and drawing of the Kalvestene in 1650. Worm recorded at least 20 settings, including three that were circular, along with what appear to be small cairns. “It’s very unusual to have an early modern description of a Viking site,” says Sebo. “Worm’s description had the potential to reveal what the site was like nearly four hundred years ago, perhaps before significant erosion had taken place or people had stolen stones for building.” However, neither the 1936 excavation nor a 2009 magnetometer survey had detected anything beyond the 10 ship settings currently visible.

Saxo likely never saw the Kalvestene, says Sebo, as no evidence exists that there was ever a barrow there. Still, his account was frequently repeated over the centuries. Among those to spread the tale was a professor and antiquarian at the University of Copenhagen named Ole Worm, who published a description and drawing of the Kalvestene in 1650. Worm recorded at least 20 settings, including three that were circular, along with what appear to be small cairns. “It’s very unusual to have an early modern description of a Viking site,” says Sebo. “Worm’s description had the potential to reveal what the site was like nearly four hundred years ago, perhaps before significant erosion had taken place or people had stolen stones for building.” However, neither the 1936 excavation nor a 2009 magnetometer survey had detected anything beyond the 10 ship settings currently visible.

In their recent survey, Sebo and a team of archaeologists documented all the extant stones, took aerial photographs, and used side-scan sonar to search for offshore remains. They detected two raised areas that might indicate previously unidentified settings and may correlate with some of those illustrated by Worm. When they compared their overall results with his drawing, Sebo says, they found that parts of the rendering are so accurate that Worm must have seen the site firsthand. But other parts appear to have been greatly exaggerated. This mix of faithful representation and invention is representative of the nature of academic inquiry of the age—and of Worm’s work in other fields. For example, he established that purported unicorn horns were actually narwhal tusks, but reportedly argued that folk wisdom attributing poison-neutralizing properties to the “horns” was sound. “In the early modern period, you are just starting to see the beginning of modern ideas of scientific accuracy,” says Sebo.

She suggests Worm embellished his drawing so the Kalvestene would resemble other landscapes of Viking Age ship settings in Denmark, which usually include cairns and settings of various shapes. In doing so, she argues, he ignored what she thinks makes the Kalvestene so interesting—the uniform shape and size of all but one of the settings. Unlike others in Denmark, they most closely resemble the much earlier settings found in southern Sweden. Perhaps, suggests Sebo, Swedish sailors who stopped at the island on their way to a nearby trading center on the mainland brought word of this style of grave field, which was then adopted by Danish locals. Centuries later, reports of the Kalvestene and the legend of King Hiarni may have been carried by sailors back to Saxo in southern Sweden, where he made them famous.

Kaleidoscopic Walls

By JASON URBANUS

Tuesday, August 10, 2021

Researchers have gained new insight into the efficiency of Roman marble production and decoration strategies employed by Roman architects. Because marble was expensive, Romans often used thin slabs as veneers, attaching them to walls built of less valuable material such as bricks. A recent study led by Cees Passchier, a geologist at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, examined 54 marble panels excavated from a second-century A.D. villa in Ephesus, Turkey. Using 3-D modeling software, Passchier and his team found that 40 of the panels had been precisely cut into 0.6-inch slices from a single block of cipollino verde, a type of greenish marble known for its elaborate wavy folds, using a water-powered sawmill. The researchers determined that the slabs were not randomly hung on the walls. Instead, sections of the block cut one after the other were mounted next to each other in pairs, like opposing pages of a book. The marble’s natural patterns created kaleidoscope-like symmetrical designs. Passchier’s team also determined that the whole process, from cutting to polishing to transportation, was extremely efficient, resulting in only 5 percent of all slabs being broken, a figure on par with present-day marble production.

Researchers have gained new insight into the efficiency of Roman marble production and decoration strategies employed by Roman architects. Because marble was expensive, Romans often used thin slabs as veneers, attaching them to walls built of less valuable material such as bricks. A recent study led by Cees Passchier, a geologist at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz, examined 54 marble panels excavated from a second-century A.D. villa in Ephesus, Turkey. Using 3-D modeling software, Passchier and his team found that 40 of the panels had been precisely cut into 0.6-inch slices from a single block of cipollino verde, a type of greenish marble known for its elaborate wavy folds, using a water-powered sawmill. The researchers determined that the slabs were not randomly hung on the walls. Instead, sections of the block cut one after the other were mounted next to each other in pairs, like opposing pages of a book. The marble’s natural patterns created kaleidoscope-like symmetrical designs. Passchier’s team also determined that the whole process, from cutting to polishing to transportation, was extremely efficient, resulting in only 5 percent of all slabs being broken, a figure on par with present-day marble production.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

The Pursuit of Wellness

Secret Rites of Samothrace

Searching for the Fisher Kings

Letter from Scotland

Digs & Discoveries

Viking Fantasy Island

Kaleidoscopic Walls

For Eternity

Maryland's First Fort

Snake Guide

Man of the Moment

Kiwi Colonists

Leisure Seekers

Neanderthal Hearing

Head of State

A Twisted Hoard

Crowning Glory

Herodian Hangout

Off the Grid

Around the World

Maya city parks, Paleoindian obsidian traders, Çatalhöyük smoke alarm, and a shark attack in Japan

Artifact

Putting a finger on fate

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement