Features

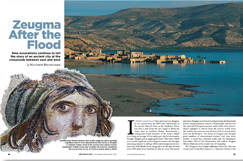

Zeugma After the Flood

By MATTHEW BRUNWASSER

Sunday, October 14, 2012

It wasn’t good policy that saved ancient Zeugma. It was a good story. In 2000, the construction of the massive Birecik Dam on the Euphrates River, less than a mile from the site, began to flood the entire area in southern Turkey. Immediately, a ticking time-bomb narrative of the waters, which were rising an average of four inches per day for six months, brought Zeugma and its plight global fame. The water, which soon would engulf the archaeological remains, also brought increasing urgency to salvage efforts and emergency excavations that had already been taking place at the site, located about 500 miles from Istanbul, for almost a year. The media attention Zeugma received attracted generous aid from both private and government sources. Of particular concern was the removal of Zeugma’s mosaics, some of the most extraordinary examples to survive from the ancient world. Soon the world’s top restorers arrived from Italy to rescue them from the floodwaters. The focus on Zeugma also brought great numbers of international tourists—and even more money—a trend that continues today with the opening in September 2011 of the ultramodern $30 million Zeugma Mosaic Museum in the nearby city of Gaziantep.

But Zeugma’s story begins millennia before the dam was constructed. In the third century B.C., Seleucus I Nicator (“the Victor”), one of Alexander the Great’s commanders, established a settlement he called Seleucia, probably a katoikia, or military colony, on the western side of the river. On its eastern bank, he founded another town he called Apamea after his Persian-born wife. The two cities were physically connected by a pontoon bridge, but it is not known whether they were administered by separate municipal governments, and nothing of ancient Apamea, nor the bridge, survives. In 64 B.C., the Romans conquered Seleucia, renaming the town Zeugma, which means “bridge” or “crossing” in ancient Greek. After the collapse of the Seleucid Empire, the Romans added Zeugma to the lands of Antiochus I Theos of Commagene as a reward for his support of General Pompey during the conquest.

Throughout the imperial period, two Roman legions were based at Zeugma, increasing its strategic value and adding to its cosmopolitan culture. Due to the high volume of road traffic and its geographic position, Zeugma became a collection point for road tolls. Political and trade routes converged here and the city was the last stop in the Greco-Roman world before crossing over to the Persian Empire. For hundreds of years Zeugma prospered as a major commercial city as well as a military and religious center, eventually reaching its peak population of about 20,000–30,000 inhabitants. During the imperial period, Zeugma became the empire’s largest, and most strategically and economically important, eastern border city.

However, the good times in Zeugma declined along with the fortunes of the Roman Empire. After the Sassanids from Persia attacked the city in A.D. 253, its luxurious villas were reduced to ruins and used as shelters for animals. The city’s new inhabitants were mainly rural people who employed only simple building materials that did not survive. Zeugma’s grandeur and importance would remain forgotten for more than 1,700 years.

|

Sidebars:

|

|

Inside the Tombs

|

Mosaic Masters

|

The Maya Sense of Time

By ZACH ZORICH

Friday, December 28, 2012

A little more than 2,000 years ago, the Maya were creating spectacular works of art and erecting massive stone buildings across what is now southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, northern Honduras, and El Salvador. As their culture spread and developed, the Maya also created a complex system of calendars that reflected an understanding of the passage of time that is very different from anything in Western culture. It is not entirely clear whether the Maya invented all of the calendars they used or whether they adopted them from the neighboring Olmec people. But over a period that may have lasted from 900 to 1,200 years they made a careful and accurate study of astronomical cycles and used that knowledge as a way to make sense of and bring order to the unpredictable world in which they lived.

The Maya recognized that the natural world, the cosmos, and even their own bodies functioned according to observable cycles. To locate themselves within these cycles they tracked the movements of planets, the moon, and the sun. They also used a 260-day calendar that many scholars believe to be based on the approximate duration of a human pregnancy. Another Maya calendar, the Long Count, was used to tally the number of days that had elapsed since the mythological date of their creation. The Long Count is set to reach the end of a 1,872,000-day-long period on December 21, 2012. (Some scholars, however, pinpoint the date as December 23.) Regardless of the date, this has given rise to widespread apocalyptic predictions about what will happen. Evidence from archaeological sites, ancient books, and the modern-day Maya themselves shows that while this one cycle is ending, many others will continue.

Zach Zorich is a senior editor at ARCHAEOLOGY

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From The Trenches

The Desert and the Dead

Fractals and Pyramids

Off the Grid

Mosaics of Huqoq

Medieval Fashion Statement

The Bog Army

Who Came to America First?

Settling Southeast Asia

Livestock for the Afterlife

Running Guns to Irish Rebels

High Rise of the Dead

Diagnosis of Ancient Illness

Pharaoh’s Port?

Peru’s Mysterious Infant Burials

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement