Features

Gaul's University Town

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Thursday, October 06, 2022

The Roman orator and rhetorician Eumenius delivered a speech to the Roman governor of Gallia Lugdunensis in A.D. 298 advocating for the restoration of the famous schools called the Maeniana in the city of Augustodunum, at the center of the province. At the time of Eumenius’ speech, the once-thriving city had fallen on hard times. In A.D. 269, its residents had taken sides against Victorinus, the emperor of the ill-fated breakaway state now known as the Gallic Empire (ca. 269–271 A.D.), and the city was besieged for seven months. Access to the high level of culture and education that had been central to Augustodunum’s identity fell victim to a combination of circumstances, perhaps including damage to the Maeniana, funding diverted to the conflict, or a diminished student population.

The Roman orator and rhetorician Eumenius delivered a speech to the Roman governor of Gallia Lugdunensis in A.D. 298 advocating for the restoration of the famous schools called the Maeniana in the city of Augustodunum, at the center of the province. At the time of Eumenius’ speech, the once-thriving city had fallen on hard times. In A.D. 269, its residents had taken sides against Victorinus, the emperor of the ill-fated breakaway state now known as the Gallic Empire (ca. 269–271 A.D.), and the city was besieged for seven months. Access to the high level of culture and education that had been central to Augustodunum’s identity fell victim to a combination of circumstances, perhaps including damage to the Maeniana, funding diverted to the conflict, or a diminished student population.

Augustodunum (modern Autun) had been founded around 13 B.C. by the emperor Augustus (r. 27 B.C.–A.D. 14) as a new capital for the Aedui, a Celtic tribe that was—mostly—allied with the Romans. By 121 B.C., the tribe had been awarded the title of “brothers and kinsmen of Rome.” The Aedui largely supported Julius Caesar in his campaigns in Gaul, with the exception of a brief defection in 52 B.C. when they joined an unsuccessful rebellion led by Vercingetorix, the doomed chief of the Arverni tribe. The capital of the Aedui had been located at the settlement of Bibracte, but when the tribe became a civitas foederata, or allied community, of Rome, it was moved 15 miles east to its new location. It was given a name that combined its Roman and Gallic identities: Augusto- for Augustus, and -dunum, the Celtic word for “hill,” “fort,” or “walled town.”

Piecing Together Maya Creation Stories

By ZACH ZORICH

Friday, July 15, 2022

Some 2,000 years ago, Maya leaders in the city of San Bartolo entered a temple chamber with vibrant murals depicting supernatural beings and mythical humans painted on its walls. Then they destroyed them.

Some 2,000 years ago, Maya leaders in the city of San Bartolo entered a temple chamber with vibrant murals depicting supernatural beings and mythical humans painted on its walls. Then they destroyed them.

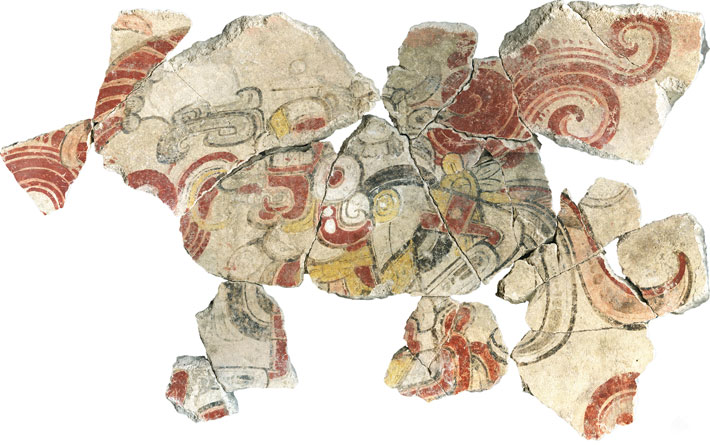

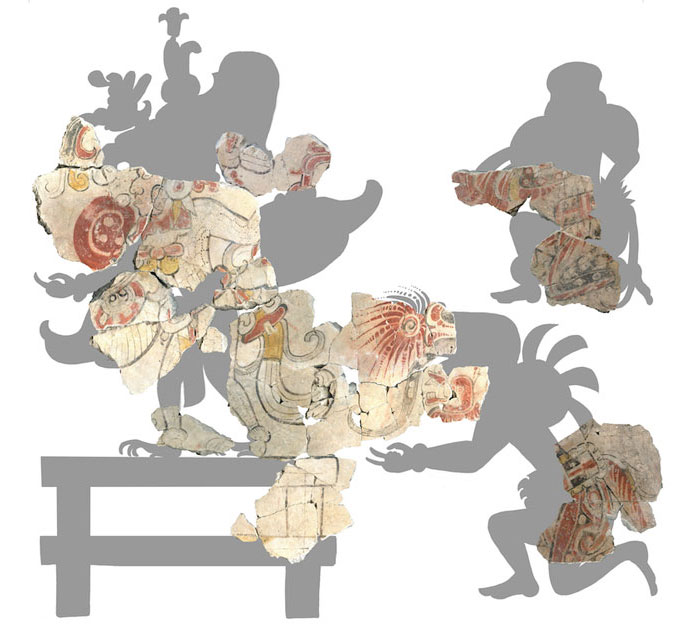

Although the murals—painted exclusively with black, red, yellow, and white pigments—had been executed by three master artists, some cycle of time known only to the city’s priests had ended, and so too had the murals’ life span. The artwork had probably been commissioned by the city’s rulers and had been on display for 50 to 100 years, but the time had come to build a new temple over the old one. This renovation meant tearing down part of the mural chamber, which was located at the base of the temple, known today as the Pyramid of Paintings.

Many of the figures painted on the chamber’s south and east walls were broken by hammer blows, and the plaster fragments containing their faces were removed. The walls were then knocked down. The chamber, which was just above ground level and opened onto a public plaza, was sealed off by a new wall. Builders faced the entire pyramid in a new layer of stone, and a new structure was built. Most of the chamber, which had been created during the sixth such renovation of the pyramid, was left relatively intact. But its remaining murals were hidden from view until 2001, when University of Boston archaeologist William Saturno discovered the chamber during a survey in Guatemala’s Petén rain forest. Until then, the site had been known only to the local Maya community.

Close study of the intact San Bartolo murals revealed that the narrative they told is an ancient version of the creation story Maya people were still recounting when the Spanish arrived in the sixteenth century. This story was recorded in an eighteenth-century text known as the Popol Vuh. These murals are among the earliest known Maya wall paintings, but their style and iconography seem to researchers to reach even further back in time. “One of the beautiful things about the discovery of San Bartolo is that it’s a distillation of a lot of key concepts of Maya cosmology in one place,” says archaeologist David Stuart of the University of Texas at Austin. “We’re looking at a system of iconography that’s already quite developed and quite old by 100 B.C.”

Close study of the intact San Bartolo murals revealed that the narrative they told is an ancient version of the creation story Maya people were still recounting when the Spanish arrived in the sixteenth century. This story was recorded in an eighteenth-century text known as the Popol Vuh. These murals are among the earliest known Maya wall paintings, but their style and iconography seem to researchers to reach even further back in time. “One of the beautiful things about the discovery of San Bartolo is that it’s a distillation of a lot of key concepts of Maya cosmology in one place,” says archaeologist David Stuart of the University of Texas at Austin. “We’re looking at a system of iconography that’s already quite developed and quite old by 100 B.C.”

Italian Master Builders

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, November 22, 2021

On a hilltop at the edge of the town of Noceto on northern Italy’s Po Plain, a 2004 construction project had gotten just a few feet into the ground when a wooden structure began to emerge. A team of archaeologists led by Mauro Cremaschi and Maria Bernabò Brea was called in to investigate. “At the beginning, we thought it was probably some sort of residential building,” says team member Andrea Zerboni, a geoarchaeologist at the University of Milan. “But soon after we started the excavation, we noticed that the sediments inside the structure weren’t related to domestic activity.” Rather than material such as ash and charcoal, typically found where people lived or worked, the structure was filled with natural sediments of the sort that would be found in a lake. The structure they were excavating was not a building at all, the researchers realized—it was an artificial pool. What they have learned about this pool in the years since has provided surprising new insights into the social organization and ritual practices of a culture that thrived in this fertile region for centuries during the second millennium B.C. before disappearing. “The Noceto pool is unique in Italy—it’s unique in the world,” says Zerboni. “Building such a structure implies very careful planning, coordinating the work of many people, and a very clear architectural plan. We don’t expect to find such majestic structures from prehistory.”

On a hilltop at the edge of the town of Noceto on northern Italy’s Po Plain, a 2004 construction project had gotten just a few feet into the ground when a wooden structure began to emerge. A team of archaeologists led by Mauro Cremaschi and Maria Bernabò Brea was called in to investigate. “At the beginning, we thought it was probably some sort of residential building,” says team member Andrea Zerboni, a geoarchaeologist at the University of Milan. “But soon after we started the excavation, we noticed that the sediments inside the structure weren’t related to domestic activity.” Rather than material such as ash and charcoal, typically found where people lived or worked, the structure was filled with natural sediments of the sort that would be found in a lake. The structure they were excavating was not a building at all, the researchers realized—it was an artificial pool. What they have learned about this pool in the years since has provided surprising new insights into the social organization and ritual practices of a culture that thrived in this fertile region for centuries during the second millennium B.C. before disappearing. “The Noceto pool is unique in Italy—it’s unique in the world,” says Zerboni. “Building such a structure implies very careful planning, coordinating the work of many people, and a very clear architectural plan. We don’t expect to find such majestic structures from prehistory.”

When they reached the bottom of the pool after several years of careful work, the archaeologists marveled at the feat of ancient engineering before them. Twenty-six wooden poles were arranged vertically to form a tank measuring roughly 40 feet long, 23 feet wide, and at least 16 feet deep. More than 240 interlocking boards lined the pool’s earthen walls and were held in place by the poles. The poles, in turn, were pressed against the walls by two networks of horizontal beams that crossed the pool perpendicular to each other. And, for good measure, a pair of long beams were arranged diagonally to buttress the four corner poles. As the researchers would learn, the pool’s builders had good reason to take extra care to ensure the soundness of their design. “When we arrived at the bottom, we said, ‘OK, our job is done, we have finished the excavation,’” says Zerboni. “But we dug a few more trenches just to check what was below the tank, and we found evidence of another wood structure.” This turned out to be an earlier attempt at building a somewhat larger tank, which had collapsed before it was completed. It’s unclear whether the earlier design simply couldn’t withstand the pressure of the earthen walls or whether one of the area’s frequent earthquakes contributed to its demise. In any case, the upper tank, whose design included additional supports, held strong for millennia.

When they reached the bottom of the pool after several years of careful work, the archaeologists marveled at the feat of ancient engineering before them. Twenty-six wooden poles were arranged vertically to form a tank measuring roughly 40 feet long, 23 feet wide, and at least 16 feet deep. More than 240 interlocking boards lined the pool’s earthen walls and were held in place by the poles. The poles, in turn, were pressed against the walls by two networks of horizontal beams that crossed the pool perpendicular to each other. And, for good measure, a pair of long beams were arranged diagonally to buttress the four corner poles. As the researchers would learn, the pool’s builders had good reason to take extra care to ensure the soundness of their design. “When we arrived at the bottom, we said, ‘OK, our job is done, we have finished the excavation,’” says Zerboni. “But we dug a few more trenches just to check what was below the tank, and we found evidence of another wood structure.” This turned out to be an earlier attempt at building a somewhat larger tank, which had collapsed before it was completed. It’s unclear whether the earlier design simply couldn’t withstand the pressure of the earthen walls or whether one of the area’s frequent earthquakes contributed to its demise. In any case, the upper tank, whose design included additional supports, held strong for millennia.

|

Slideshow:

|

Bronze Age Ritual Pool

|

Ghost Tracks of White Sands

By KAREN COATES

Tuesday, February 01, 2022

The sun shines nearly 300 days a year over southern New Mexico’s Tularosa Basin, where bright white sand ripples across the desert. Here, in White Sands National Park, the world’s largest gypsum dunes abut the dried-up bed of prehistoric Lake Otero, which once covered 1,600 square miles. In the summer, park temperatures can soar to 110°F, and the intense sunlight stings the eyes. It was one of those hot but slightly hazy days in May 2021 when Bonnie Leno and Kim Charlie, sisters from Acoma Pueblo, about 175 miles north, found the fossilized tracks of a giant ground sloth and two humans, all of whom lived at least 10,000 years ago, at the close of the Pleistocene Epoch.

The sun shines nearly 300 days a year over southern New Mexico’s Tularosa Basin, where bright white sand ripples across the desert. Here, in White Sands National Park, the world’s largest gypsum dunes abut the dried-up bed of prehistoric Lake Otero, which once covered 1,600 square miles. In the summer, park temperatures can soar to 110°F, and the intense sunlight stings the eyes. It was one of those hot but slightly hazy days in May 2021 when Bonnie Leno and Kim Charlie, sisters from Acoma Pueblo, about 175 miles north, found the fossilized tracks of a giant ground sloth and two humans, all of whom lived at least 10,000 years ago, at the close of the Pleistocene Epoch.

Leno and Charlie didn’t expect to uncover evidence of ancient history at the park, but there they were, the kidney-shaped footprints of a 10-foot-tall, 2,000-pound long-extinct mammal and the imprints of human toes—the marks of two species that coexisted thousands of years ago. “I was down on the ground, brushing everything off,” says Leno, recalling the adult human footprint she found not far below the surface. “I was ecstatic.” Just inches away, she spotted the giant sloth track. “There were a lot of prints in that area,” says Charlie, who uncovered the tiny footprint of a child nearby.

Charlie is a member of the Acoma Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) board and participates in a consultation program with the National Park Service. Any time park employees conduct studies that might affect a Native cultural site, pueblos and tribes affiliated with that site are asked to consult on the research and preservation. Acoma is one of six Native groups currently studying and protecting the park’s prehistoric trackways, says David Bustos, White Sands’ resource program manager. He invited Charlie to accompany scientists and park staff on one of the first field trips to the park since the pandemic began in 2020. She in turn asked Leno, an Acoma cultural monitor who works with the THPO to study and assess archaeological sites in culturally sensitive areas. It’s a role that the sisters say is akin to retracing their ancestral footsteps.

White Sands has the world’s largest collection of fossilized Ice Age footprints, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. For several years, a team of archaeologists, geographers, geologists, environmental scientists, and tribal members has worked to find and analyze as many prints as possible. No one knows who the early human trackmakers were or whether they were genetically related to Native groups in the region today, but recent findings suggest people walked through these lands far earlier than scientists commonly thought. In 2019, researchers found human tracks amid sediment layers containing seeds from an aquatic plant that grew around the ancient lake. The discovery presented a rare opportunity—the scientists could radiocarbon date the seeds to derive an approximate age of the footprints. The results confirmed the presence of humans there between 23,000 and 21,000 years ago, at a time when much of modern-day North America was under ice. That discovery revived longstanding questions about how and when people first inhabited the continent. If the dates are correct, they would disprove a commonly held theory that humans arrived thousands of years later, toward the end of the Ice Age.

White Sands has the world’s largest collection of fossilized Ice Age footprints, numbering in the hundreds of thousands. For several years, a team of archaeologists, geographers, geologists, environmental scientists, and tribal members has worked to find and analyze as many prints as possible. No one knows who the early human trackmakers were or whether they were genetically related to Native groups in the region today, but recent findings suggest people walked through these lands far earlier than scientists commonly thought. In 2019, researchers found human tracks amid sediment layers containing seeds from an aquatic plant that grew around the ancient lake. The discovery presented a rare opportunity—the scientists could radiocarbon date the seeds to derive an approximate age of the footprints. The results confirmed the presence of humans there between 23,000 and 21,000 years ago, at a time when much of modern-day North America was under ice. That discovery revived longstanding questions about how and when people first inhabited the continent. If the dates are correct, they would disprove a commonly held theory that humans arrived thousands of years later, toward the end of the Ice Age.

When Isis Was Queen

By ISMA’IL KUSHKUSH

Tuesday, October 12, 2021

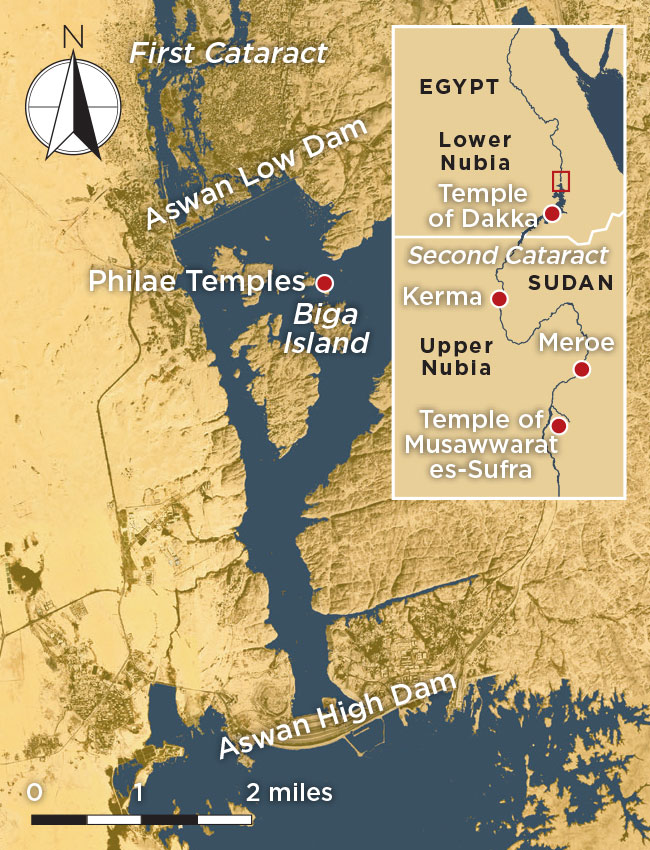

When the Romans conquered Egypt in 30 B.C., the country’s system of temples, which had sustained religious traditions dating back more than 3,000 years, began to slowly wither away. Starved of the funds that pharaohs traditionally supplied to religious institutions, priests lost their vocation and temples fell into disuse throughout the country. The introduction of Christianity in the first century a.d. only hastened this process. But there was one exception to this trend: In the temples on the island of Philae in the Nile River, rites dedicated to the goddess Isis and the god Osiris continued to be celebrated in high style for some 500 years after the Roman conquest. This final flowering of ancient Egyptian religion was only possible because of the piety and support of Egypt’s neighbors to the south, the Nubians.

When the Romans conquered Egypt in 30 B.C., the country’s system of temples, which had sustained religious traditions dating back more than 3,000 years, began to slowly wither away. Starved of the funds that pharaohs traditionally supplied to religious institutions, priests lost their vocation and temples fell into disuse throughout the country. The introduction of Christianity in the first century a.d. only hastened this process. But there was one exception to this trend: In the temples on the island of Philae in the Nile River, rites dedicated to the goddess Isis and the god Osiris continued to be celebrated in high style for some 500 years after the Roman conquest. This final flowering of ancient Egyptian religion was only possible because of the piety and support of Egypt’s neighbors to the south, the Nubians.

Philae lies just south of the Nile’s first cataract—one of six rapids along the river—which marked the historical border between ancient Egypt and Nubia, also known as Kush. In this region of Kush, called Lower Nubia, the temple complex at Philae was just one of many that were built on islands in the Nile and along its banks. Throughout the long history of Egypt and Nubia, Lower Nubia was a kind of buffer zone between these two lands and a place where the two cultures heavily influenced one another. “Often official Egyptian texts were demeaning to Nubians,” says Egyptologist Solange Ashby of the University of California, Los Angeles. “But this cultural arrogance doesn’t reflect the lived reality of Egyptians and Nubians being neighbors, intermarrying, sharing cultural and religious practices. These were people who interacted for millennia.”

Philae lies just south of the Nile’s first cataract—one of six rapids along the river—which marked the historical border between ancient Egypt and Nubia, also known as Kush. In this region of Kush, called Lower Nubia, the temple complex at Philae was just one of many that were built on islands in the Nile and along its banks. Throughout the long history of Egypt and Nubia, Lower Nubia was a kind of buffer zone between these two lands and a place where the two cultures heavily influenced one another. “Often official Egyptian texts were demeaning to Nubians,” says Egyptologist Solange Ashby of the University of California, Los Angeles. “But this cultural arrogance doesn’t reflect the lived reality of Egyptians and Nubians being neighbors, intermarrying, sharing cultural and religious practices. These were people who interacted for millennia.”

From 300 B.C. to A.D. 300, Nubia was ruled from the capital city of Meroe. The Meroitic kings took a special interest in Philae, where the most important Egyptian temple dedicated to Isis was located. In part this may have been because the island had been significant to the Nubians for centuries. Even its ancient Egyptian name, Pilak, which means “Island of Time” or “Island of Extremity,” may have been of Nubian origin. And while many of the other temples on Philae were built by Egypt’s Ptolemaic kings, Greek rulers who held sway from 304 to 30 B.C., the continued survival of the religious practices there owed much to the Meroitic kings. They, and later other Nubian rulers, funded annual celebrations at Philae and devoted resources to maintaining its temples in the centuries before Christianity finally eclipsed Egypt’s ancient traditions.

|

Sidebar:

|

The Cult of Isis

|

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

When Isis Was Queen

Italian Master Builders

Ghost Tracks of White Sands

Piecing Together Maya Creation Stories

Gaul's University Town

Letter from Ghana

Digs & Discoveries

Identifying the Unidentified

In Full Color

Typing Time

Otto's Church

An Irish Idol

A Family's Final Resting Place

A Place of Their Own

A Trip to Venice

Salty Snack

The Age of Glass

China's New Human Species

Mesopotamian War Memorial

Off the Grid

Around the World

Under the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, Ice Age camping in Michigan, and a Mesolithic Russian amber merchant

Artifact

Lost in translation

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

From the start, Augustodunum was a city with a status and appearance befitting the prestige of the Aedui and their Roman governors. The provincial capital city of Lugdunum (modern Lyon), a little over 100 miles south, was its only superior in architectural splendor, economic prominence, and population in the region. “Augustodunum was one of the most important cities in Gaul,” says archaeologist Carole Fossurier of France’s National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP). For most of the nearly three centuries preceding Eumenius’ oration, it was a thriving university town and one of the most Romanized in Gaul. It was encircled by a stout 4.5-mile city wall that enclosed an area of about 500 acres, with straight Roman streets laid out on a grid plan. It was also home to Gaul’s largest theater, an amphitheater, shops, manufacturing quarters, public baths, luxuriously decorated residences, a forum, numerous temples, and, eventually, places for Christian worship. The city was traversed by a major Roman road built by Augustus’ son-in-law Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa for military use and to encourage trade by connecting the province to the English Channel. Under the emperor Claudius (r. A.D. 41–54), who was born in Lugdunum, the Aedui became the first Gallic tribe whose members were allowed to serve as senators in Rome. In Augustodunum, writes the first- and second-century A.D. Roman historian Tacitus, “the noblest youth of Gaul devoted themselves to a liberal education.”

From the start, Augustodunum was a city with a status and appearance befitting the prestige of the Aedui and their Roman governors. The provincial capital city of Lugdunum (modern Lyon), a little over 100 miles south, was its only superior in architectural splendor, economic prominence, and population in the region. “Augustodunum was one of the most important cities in Gaul,” says archaeologist Carole Fossurier of France’s National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP). For most of the nearly three centuries preceding Eumenius’ oration, it was a thriving university town and one of the most Romanized in Gaul. It was encircled by a stout 4.5-mile city wall that enclosed an area of about 500 acres, with straight Roman streets laid out on a grid plan. It was also home to Gaul’s largest theater, an amphitheater, shops, manufacturing quarters, public baths, luxuriously decorated residences, a forum, numerous temples, and, eventually, places for Christian worship. The city was traversed by a major Roman road built by Augustus’ son-in-law Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa for military use and to encourage trade by connecting the province to the English Channel. Under the emperor Claudius (r. A.D. 41–54), who was born in Lugdunum, the Aedui became the first Gallic tribe whose members were allowed to serve as senators in Rome. In Augustodunum, writes the first- and second-century A.D. Roman historian Tacitus, “the noblest youth of Gaul devoted themselves to a liberal education.” After the siege by Victorinus that damaged the city, the emperor Constantius I (r. A.D. 293–306) became Augustodunum’s benefactor. He promised to restore the city to its former status and appearance, an effort that was continued by his son, the emperor Constantine I (r. A.D. 306–337). “Augustodunum wanted to be a provincial capital,” says University of Kent archaeologist Luke Lavan, “and to become one, it competed with other provincial centers in Gaul for the emperor’s patronage.”

After the siege by Victorinus that damaged the city, the emperor Constantius I (r. A.D. 293–306) became Augustodunum’s benefactor. He promised to restore the city to its former status and appearance, an effort that was continued by his son, the emperor Constantine I (r. A.D. 306–337). “Augustodunum wanted to be a provincial capital,” says University of Kent archaeologist Luke Lavan, “and to become one, it competed with other provincial centers in Gaul for the emperor’s patronage.” Archaeologists have explored Autun periodically for decades. Still, very little of Augustodunum—perhaps only 3 to 4 percent—has been investigated, and only through small surveys, limited excavations, and sometimes accidental discoveries. Researchers have unearthed the remnants of ancient structures, including possibly the Maeniana, as well as aqueducts, marble sculptures, and finely crafted mosaics that once covered the floors of the city’s wealthiest residents’ homes. Some of these mosaics depict scenes from Greek mythology, such as the story of the hero Bellerophon, who killed the mythical beast the Chimera. Others include portraits and sayings of Greek philosophers. These are testaments to the influence of Greco-Roman high culture in Augustodunum and to its well-educated citizenry. Part of Augustodunum’s fourth-century A.D. church was excavated in the 1970s, and several acres of one its largest ancient cemeteries were dug in 2004.

Archaeologists have explored Autun periodically for decades. Still, very little of Augustodunum—perhaps only 3 to 4 percent—has been investigated, and only through small surveys, limited excavations, and sometimes accidental discoveries. Researchers have unearthed the remnants of ancient structures, including possibly the Maeniana, as well as aqueducts, marble sculptures, and finely crafted mosaics that once covered the floors of the city’s wealthiest residents’ homes. Some of these mosaics depict scenes from Greek mythology, such as the story of the hero Bellerophon, who killed the mythical beast the Chimera. Others include portraits and sayings of Greek philosophers. These are testaments to the influence of Greco-Roman high culture in Augustodunum and to its well-educated citizenry. Part of Augustodunum’s fourth-century A.D. church was excavated in the 1970s, and several acres of one its largest ancient cemeteries were dug in 2004. In 2020, INRAP archaeologists Fossurier and Nicolas Tisserand led an excavation, which they have since completed, in an area of Autun known as Saint-Pierre-l’Estrier. There they uncovered new evidence of the lives and deaths of Augustodunum’s residents. On the site where a house was being built, they made a spectacular discovery—a necropolis containing more than 250 burials dating to the third through fifth centuries a.d. The graves represent a variety of religions and economic statuses and contain some of the most valuable artifacts from the Roman world.

In 2020, INRAP archaeologists Fossurier and Nicolas Tisserand led an excavation, which they have since completed, in an area of Autun known as Saint-Pierre-l’Estrier. There they uncovered new evidence of the lives and deaths of Augustodunum’s residents. On the site where a house was being built, they made a spectacular discovery—a necropolis containing more than 250 burials dating to the third through fifth centuries a.d. The graves represent a variety of religions and economic statuses and contain some of the most valuable artifacts from the Roman world. Nevertheless, the necropolis provides scholars with a wide-ranging opportunity to learn about the burial practices used in Augustodunum at the time. “The diversity of burial methods probably illustrates the diversity of the society in this period,” says Fossurier. “People whose status seems to have differed were interred side by side in the necropolis, and the variety of funerary containers and accompanying goods indicates that the cemetery was used for common people as well as the high-status rich or the very rich. We also know that men, women, and children were buried there.”

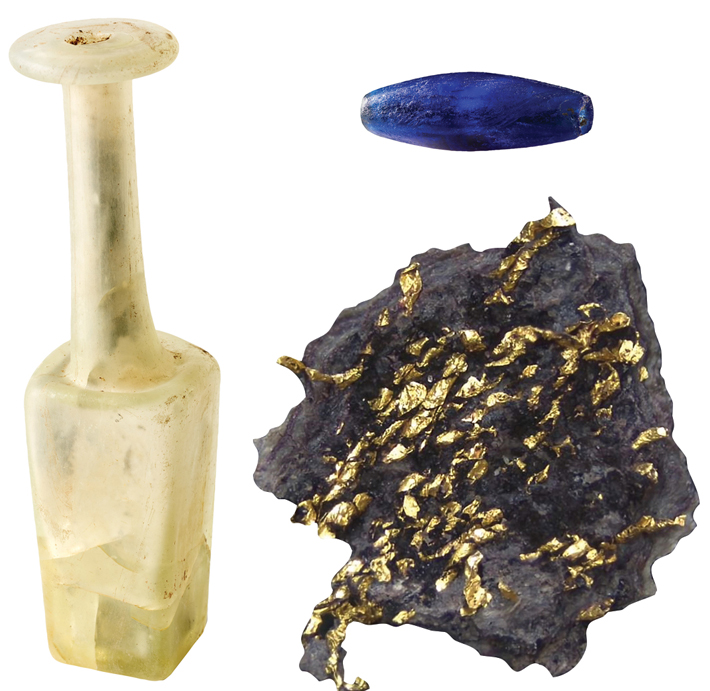

Nevertheless, the necropolis provides scholars with a wide-ranging opportunity to learn about the burial practices used in Augustodunum at the time. “The diversity of burial methods probably illustrates the diversity of the society in this period,” says Fossurier. “People whose status seems to have differed were interred side by side in the necropolis, and the variety of funerary containers and accompanying goods indicates that the cemetery was used for common people as well as the high-status rich or the very rich. We also know that men, women, and children were buried there.” In the largest sarcophagus, which was deeply buried and sealed with iron spikes, the team found a gold hair ornament, a gold ring with a garnet, and a collection of pins made of amber. These pins, says Tisserand, are similar to examples made from other materials, but are the only known pins of this style carved from amber in the Roman world. Other burials contained pins and bracelets made of jet, a blue glass bead, coins, several glass and ceramic vessels, a child’s pair of gold earrings, and a copper-alloy belt buckle shaped like an amphora. The archaeologists also discovered dyed textile fragments, some of which were woven with gold threads. The pigment, characteristic of very wealthy burials of the period in the region, was extracted from the glands of murex snails from the Mediterranean.

In the largest sarcophagus, which was deeply buried and sealed with iron spikes, the team found a gold hair ornament, a gold ring with a garnet, and a collection of pins made of amber. These pins, says Tisserand, are similar to examples made from other materials, but are the only known pins of this style carved from amber in the Roman world. Other burials contained pins and bracelets made of jet, a blue glass bead, coins, several glass and ceramic vessels, a child’s pair of gold earrings, and a copper-alloy belt buckle shaped like an amphora. The archaeologists also discovered dyed textile fragments, some of which were woven with gold threads. The pigment, characteristic of very wealthy burials of the period in the region, was extracted from the glands of murex snails from the Mediterranean. The chamber’s destruction initially obscured the narrative’s beginning and end. According to Skidmore College archaeologist and National Geographic Explorer Heather Hurst, who codirects the San Bartolo Project with her colleague Boris Beltrán, also of Skidmore College, the destruction was not simply part of the building’s renovation. It was also part of a ritual that commemorated the end of one cycle of time and the beginning of another. Since painting the chamber had imbued it with supernatural significance, destroying some of the murals to clear the way for the renewed temple without acknowledging and managing the paintings’ power could have meant angering supernatural beings. “You can’t just bury it,” says Hurst. “As the new temple is built, you are honoring the temple that came before it.”

The chamber’s destruction initially obscured the narrative’s beginning and end. According to Skidmore College archaeologist and National Geographic Explorer Heather Hurst, who codirects the San Bartolo Project with her colleague Boris Beltrán, also of Skidmore College, the destruction was not simply part of the building’s renovation. It was also part of a ritual that commemorated the end of one cycle of time and the beginning of another. Since painting the chamber had imbued it with supernatural significance, destroying some of the murals to clear the way for the renewed temple without acknowledging and managing the paintings’ power could have meant angering supernatural beings. “You can’t just bury it,” says Hurst. “As the new temple is built, you are honoring the temple that came before it.”

At the center of the second scene, an image depicts Earth as a turtle floating in primordial waters, reflecting the ancient Maya belief that they lived on the back of a turtle swimming in the ocean. Inside the image of the turtle, the maize god dances and plays a turtle-shell drum.

At the center of the second scene, an image depicts Earth as a turtle floating in primordial waters, reflecting the ancient Maya belief that they lived on the back of a turtle swimming in the ocean. Inside the image of the turtle, the maize god dances and plays a turtle-shell drum. The next scene is the best preserved of the narrative. It shows four young men standing and offering sacrifices in front of supernatural trees that anchor Earth at its four cardinal directions. At the top of each tree sits a monstrous bird scholars have named the Principal Bird Deity. According to Taube, the bird deity has a dual nature—it is associated with creation and the sun but also with darkness. The tree closest to the center of the scene has the twisted trunk of a gourd tree. The bird deity is shown descending from heaven to land in it.

The next scene is the best preserved of the narrative. It shows four young men standing and offering sacrifices in front of supernatural trees that anchor Earth at its four cardinal directions. At the top of each tree sits a monstrous bird scholars have named the Principal Bird Deity. According to Taube, the bird deity has a dual nature—it is associated with creation and the sun but also with darkness. The tree closest to the center of the scene has the twisted trunk of a gourd tree. The bird deity is shown descending from heaven to land in it. The last scene is from the destroyed south wall and has been entirely reconstructed from fragments. It takes viewers into the underworld and though it is the least complete scene, it has several identifiable figures. The most complete image depicts an aspect of the sun god known as the solar eagle, according to Stuart and Taube. The deity has the glyph for “sun” painted on his cheek. Above the sun god is a depiction of an obscure god named Wak Tok. Stuart believes that Wak Tok is related to the rain god Chahk, but very little is known about the deity. There is only one other reference to Wak Tok, which dates to A.D. 700 and was found on a stone panel at the site of Palenque in southern Mexico. “We are missing much of this mythical religious knowledge,” Stuart says, adding that it was probably kept in books that have not survived. “We just happen to see little pieces of this lost world, and Wak Tok Chahk is a great example of a Maya deity who was important enough to be in the murals, yet there are only two mentions of him anywhere in the Maya region.”

The last scene is from the destroyed south wall and has been entirely reconstructed from fragments. It takes viewers into the underworld and though it is the least complete scene, it has several identifiable figures. The most complete image depicts an aspect of the sun god known as the solar eagle, according to Stuart and Taube. The deity has the glyph for “sun” painted on his cheek. Above the sun god is a depiction of an obscure god named Wak Tok. Stuart believes that Wak Tok is related to the rain god Chahk, but very little is known about the deity. There is only one other reference to Wak Tok, which dates to A.D. 700 and was found on a stone panel at the site of Palenque in southern Mexico. “We are missing much of this mythical religious knowledge,” Stuart says, adding that it was probably kept in books that have not survived. “We just happen to see little pieces of this lost world, and Wak Tok Chahk is a great example of a Maya deity who was important enough to be in the murals, yet there are only two mentions of him anywhere in the Maya region.” The chamber at the base of the Pyramid of the Paintings isn’t the only space in the building that was furnished with such rich visual narratives. During the same construction phase in which the lower chamber was built, another chamber was constructed at the top of the temple. Its interior was once decorated with its own finely painted murals. The archaeologists have named this chamber Ixim, which is one of the Maya’s words for maize.

The chamber at the base of the Pyramid of the Paintings isn’t the only space in the building that was furnished with such rich visual narratives. During the same construction phase in which the lower chamber was built, another chamber was constructed at the top of the temple. Its interior was once decorated with its own finely painted murals. The archaeologists have named this chamber Ixim, which is one of the Maya’s words for maize. The team found no indication that the pool had served any practical purpose. There was no sign of a mechanism for channeling water in or out, and the fine-grained sediments had accumulated slowly at the pool’s bottom without the sort of regular disturbance that would have occurred if it had served as a reservoir. Their excavations did, however, uncover an extensive array of material in the pool. The finds include around 150 complete vases and 25 miniature vessels, which pottery experts dated to this region’s Middle Bronze Age (ca. 1600–1300 B.C.). Zerboni notes that the pottery found in the pool is of a type that would have been highly valued and used only for special occasions. The excavators also uncovered seven small clay votive figurines depicting horses, pigs, cows, and, in one instance, an anthropomorphic figure. Similar examples from the period in Europe are known, but are quite rare, says Zerboni. A large number of animal remains were unearthed as well, primarily deer antlers, but also a complete skeleton of a baby pig. There were spindles, numerous baskets, and several large blocks of wood, as well as hundreds of wooden farming tools, including four whole and fragmentary plows. These items had all been carefully deposited in the pool in distinct layers, as if during multiple events. “From this evidence, and from the greatness of the structure, we started thinking it was related to some sort of ritual,” says Zerboni. “The Noceto pool was probably built to celebrate something.”

The team found no indication that the pool had served any practical purpose. There was no sign of a mechanism for channeling water in or out, and the fine-grained sediments had accumulated slowly at the pool’s bottom without the sort of regular disturbance that would have occurred if it had served as a reservoir. Their excavations did, however, uncover an extensive array of material in the pool. The finds include around 150 complete vases and 25 miniature vessels, which pottery experts dated to this region’s Middle Bronze Age (ca. 1600–1300 B.C.). Zerboni notes that the pottery found in the pool is of a type that would have been highly valued and used only for special occasions. The excavators also uncovered seven small clay votive figurines depicting horses, pigs, cows, and, in one instance, an anthropomorphic figure. Similar examples from the period in Europe are known, but are quite rare, says Zerboni. A large number of animal remains were unearthed as well, primarily deer antlers, but also a complete skeleton of a baby pig. There were spindles, numerous baskets, and several large blocks of wood, as well as hundreds of wooden farming tools, including four whole and fragmentary plows. These items had all been carefully deposited in the pool in distinct layers, as if during multiple events. “From this evidence, and from the greatness of the structure, we started thinking it was related to some sort of ritual,” says Zerboni. “The Noceto pool was probably built to celebrate something.” During the Middle Bronze Age, farmers belonging to a culture known as the Terramare settled the Po Plain, which is bordered by the Alps to the north and west, the Apennine Mountains to the south, and the Adriatic Sea to the east. The Terramare completely cleared the area’s forests and intensively cultivated the land. The landscape proved bountiful, producing bumper crops of wheat, barley, and other cereals, and supporting plentiful herds of livestock including sheep, goats, and pigs. To further their agricultural endeavors, the Terramare embarked on extensive irrigation projects. They located their settlements along the Po River and its tributaries, and dug a large number of wells. These settlements were surrounded by moats, which were at once defensive features and additional sources of water. The Terramare built their houses on wood piles, using timber harvested from the rapidly depleting forests.

During the Middle Bronze Age, farmers belonging to a culture known as the Terramare settled the Po Plain, which is bordered by the Alps to the north and west, the Apennine Mountains to the south, and the Adriatic Sea to the east. The Terramare completely cleared the area’s forests and intensively cultivated the land. The landscape proved bountiful, producing bumper crops of wheat, barley, and other cereals, and supporting plentiful herds of livestock including sheep, goats, and pigs. To further their agricultural endeavors, the Terramare embarked on extensive irrigation projects. They located their settlements along the Po River and its tributaries, and dug a large number of wells. These settlements were surrounded by moats, which were at once defensive features and additional sources of water. The Terramare built their houses on wood piles, using timber harvested from the rapidly depleting forests. This technique gave the team a far more precise date than had been possible using pottery styles or conventional radiocarbon dating. It placed the pool’s construction very close to a time when a major shift in the Terramare culture occurred. Around 1450 B.C., the number of Terramare settlements increased and some grew much larger. The overall population also increased and people exploited the land more aggressively. There are indications that what had been a relatively egalitarian society grew more hierarchical at this point. To Zerboni, the pool and the items deposited in it were likely intended to represent many of the elements contributing to the culture’s success. These included wood, which they used to build their villages; farming tools, which they used to work the land; and water, which they used to nourish crops. “These were probably offerings to a divinity or to nature to show how grateful they were,” Zerboni says. “The pool was a sort of monument intended to celebrate the agriculture and the natural resources that supported their community.”

This technique gave the team a far more precise date than had been possible using pottery styles or conventional radiocarbon dating. It placed the pool’s construction very close to a time when a major shift in the Terramare culture occurred. Around 1450 B.C., the number of Terramare settlements increased and some grew much larger. The overall population also increased and people exploited the land more aggressively. There are indications that what had been a relatively egalitarian society grew more hierarchical at this point. To Zerboni, the pool and the items deposited in it were likely intended to represent many of the elements contributing to the culture’s success. These included wood, which they used to build their villages; farming tools, which they used to work the land; and water, which they used to nourish crops. “These were probably offerings to a divinity or to nature to show how grateful they were,” Zerboni says. “The pool was a sort of monument intended to celebrate the agriculture and the natural resources that supported their community.” Manning believes that the process of building the pool may have helped fortify the hierarchy that appears to have developed as the Terramare population exploded. “You might speculate that this is the sort of group building and regional collective activity that an ambitious ruler or priest might engage in to link together a community or even a couple of communities,” he says. “Creating the thing means people have to gather together, work together, create a common purpose, and then it becomes a sort of venue to come and visit afterwards.” Those members of the community who climbed the hill to gaze into the pool’s waters might have been rewarded with a transcendent experience. “You could almost see this as a mirror in which you would have been both looking at the reflection of the world around you, but also looking through it to see some form of netherworld or underworld,” Manning says. “I wonder if this wasn’t symbolic of connections between the divine and the earthly for these people.”

Manning believes that the process of building the pool may have helped fortify the hierarchy that appears to have developed as the Terramare population exploded. “You might speculate that this is the sort of group building and regional collective activity that an ambitious ruler or priest might engage in to link together a community or even a couple of communities,” he says. “Creating the thing means people have to gather together, work together, create a common purpose, and then it becomes a sort of venue to come and visit afterwards.” Those members of the community who climbed the hill to gaze into the pool’s waters might have been rewarded with a transcendent experience. “You could almost see this as a mirror in which you would have been both looking at the reflection of the world around you, but also looking through it to see some form of netherworld or underworld,” Manning says. “I wonder if this wasn’t symbolic of connections between the divine and the earthly for these people.” For Leno and Charlie, the new dates simply confirm the histories Native people have long understood. “We’ve always stressed that we’ve been here,” Charlie says. “We’ve always stressed that we’re the Indigenous people that lived here on this continent.” She and Leno don’t know whether their family has a direct ancestral line to the White Sands walkers, but there’s no denying the sisters’ sense of connection to the trackways and the people who made them. “Even though it’s been thousands of years,” Charlie says, the tracks “are still a part of us.”

For Leno and Charlie, the new dates simply confirm the histories Native people have long understood. “We’ve always stressed that we’ve been here,” Charlie says. “We’ve always stressed that we’re the Indigenous people that lived here on this continent.” She and Leno don’t know whether their family has a direct ancestral line to the White Sands walkers, but there’s no denying the sisters’ sense of connection to the trackways and the people who made them. “Even though it’s been thousands of years,” Charlie says, the tracks “are still a part of us.” Today, the White Sands landscape, with its crests of glimmering dunes, forms a panorama of snow-white land in a summer broil. There are no trees, save for a few solitary invasive species that suck whatever moisture they can from the land. Miles of undulating sands give way to the crisp, flat surface of the dried-up ancient Lake Otero, which is dotted with iodine bush, a desert shrub adapted to sandy, salty, alkaline soils. To the east and west of the park, a heat haze distorts the peaks of towering mountains; to the north is White Sands Missile Range, the U.S. Army’s largest land-based open-air testing site. But the ancient trackways follow no modern borders—footprints crisscross both sides of the fence dividing the national park from the missile range.

Today, the White Sands landscape, with its crests of glimmering dunes, forms a panorama of snow-white land in a summer broil. There are no trees, save for a few solitary invasive species that suck whatever moisture they can from the land. Miles of undulating sands give way to the crisp, flat surface of the dried-up ancient Lake Otero, which is dotted with iodine bush, a desert shrub adapted to sandy, salty, alkaline soils. To the east and west of the park, a heat haze distorts the peaks of towering mountains; to the north is White Sands Missile Range, the U.S. Army’s largest land-based open-air testing site. But the ancient trackways follow no modern borders—footprints crisscross both sides of the fence dividing the national park from the missile range. At the time when many of the tracks were made, researchers think Lake Otero had already begun to evaporate and a series of small seasonal bodies of water covered the area. As the water evaporated over time, it formed a playa—the flat bottom of a desert basin that occasionally fills with water. About 15 years ago, a rare flood filled that playa with so much water that waves beat against the ancient shoreline and eroded its sediments, exposing trackways never before seen. Not long after that, Bustos began finding prints left by mammoths on the shoreline as well as elongated prints he thought might be human. As time passed, he and other researchers found more and more trackways from what appeared to be an array of species, including humans, mammoths, bison, camels, dire wolves, and saber-toothed cats. Some of the marks show evidence of people and animals slipping and sliding across what was then a muddy surface. “Many of the footprints actually have layers of algae, which would have required moisture to grow,” says Cornell University archaeologist and team member Tommy Urban.

At the time when many of the tracks were made, researchers think Lake Otero had already begun to evaporate and a series of small seasonal bodies of water covered the area. As the water evaporated over time, it formed a playa—the flat bottom of a desert basin that occasionally fills with water. About 15 years ago, a rare flood filled that playa with so much water that waves beat against the ancient shoreline and eroded its sediments, exposing trackways never before seen. Not long after that, Bustos began finding prints left by mammoths on the shoreline as well as elongated prints he thought might be human. As time passed, he and other researchers found more and more trackways from what appeared to be an array of species, including humans, mammoths, bison, camels, dire wolves, and saber-toothed cats. Some of the marks show evidence of people and animals slipping and sliding across what was then a muddy surface. “Many of the footprints actually have layers of algae, which would have required moisture to grow,” says Cornell University archaeologist and team member Tommy Urban. So many footprints emerged that park staff sought guidance from Bournemouth University fossil footprint expert Matthew Bennett, who visited White Sands in 2017 and confirmed the presence of human and animal tracks. He has since made 10 trips to the park, and has no doubt that White Sands is one of the world’s most significant track sites, with tens of thousands of trackways. By comparison, Laetoli, the Tanzanian site with the world’s oldest-known hominin footprints, extends about 88 feet and contains fewer than 100 tracks.

So many footprints emerged that park staff sought guidance from Bournemouth University fossil footprint expert Matthew Bennett, who visited White Sands in 2017 and confirmed the presence of human and animal tracks. He has since made 10 trips to the park, and has no doubt that White Sands is one of the world’s most significant track sites, with tens of thousands of trackways. By comparison, Laetoli, the Tanzanian site with the world’s oldest-known hominin footprints, extends about 88 feet and contains fewer than 100 tracks. The researchers concluded that the chaperone on the excursion at times carried the toddler, shifting the child from hip to hip. This subtle change in behavior is reflected in the alternating shape of the footprints, which broaden with added weight to form a banana shape created by the outward rotation of the older person’s foot. They can also tell this was a speedy trip, completed at a pace of 5.5 feet per second through slick mud—far faster than that of a person walking at a comfortable pace of four feet per second over dry, flat land. They determined this by creating a mosaic of aerial images of a large section of the trackway that encompassed hundreds of prints. This allowed them to calculate the people’s average stride lengths. The researchers don’t know the purpose of the trek, or why it was made so quickly, except to note that the dangerous beasts of the Ice Age world would have given people plenty of reasons to hurry, especially with a child in tow.

The researchers concluded that the chaperone on the excursion at times carried the toddler, shifting the child from hip to hip. This subtle change in behavior is reflected in the alternating shape of the footprints, which broaden with added weight to form a banana shape created by the outward rotation of the older person’s foot. They can also tell this was a speedy trip, completed at a pace of 5.5 feet per second through slick mud—far faster than that of a person walking at a comfortable pace of four feet per second over dry, flat land. They determined this by creating a mosaic of aerial images of a large section of the trackway that encompassed hundreds of prints. This allowed them to calculate the people’s average stride lengths. The researchers don’t know the purpose of the trek, or why it was made so quickly, except to note that the dangerous beasts of the Ice Age world would have given people plenty of reasons to hurry, especially with a child in tow. With the exception of the trackways discovered in 2019, researchers have not yet been able to precisely date the footprints at White Sands. The team isn’t certain what cultures the trackmakers belonged to or when exactly they lived. “We’re dating them on the basis of the coexistence with the animals, which have known extinction dates,” says Urban. The team estimates that many of the tracks were made between 15,500 and 10,000 years ago, during a period that overlaps with the widespread North American Clovis culture, as well as the later Folsom tradition. Both peoples were hunter-gatherers who lived in small groups and are known today for their distinctive tools. Characteristic flaked Clovis spearpoints have been found with the bones of megafauna such as mammoth, and smaller worked Folsom points are often associated with bison kill sites. The White Sands tracks indicate the people—whoever they were—followed, stalked, harassed, and possibly hunted big game.

With the exception of the trackways discovered in 2019, researchers have not yet been able to precisely date the footprints at White Sands. The team isn’t certain what cultures the trackmakers belonged to or when exactly they lived. “We’re dating them on the basis of the coexistence with the animals, which have known extinction dates,” says Urban. The team estimates that many of the tracks were made between 15,500 and 10,000 years ago, during a period that overlaps with the widespread North American Clovis culture, as well as the later Folsom tradition. Both peoples were hunter-gatherers who lived in small groups and are known today for their distinctive tools. Characteristic flaked Clovis spearpoints have been found with the bones of megafauna such as mammoth, and smaller worked Folsom points are often associated with bison kill sites. The White Sands tracks indicate the people—whoever they were—followed, stalked, harassed, and possibly hunted big game. The team is documenting trackways as rapidly as they can, using an array of tools to locate new prints and quickly gather information from those already identified. While erosion constantly exposes new trackways, the team also searches for those that are less visible. Urban has spent most of his time in the park conducting geophysical surveys using magnetometry and ground-penetrating radar, which allow researchers to create images of tracks that lie below the surface. The team then uses traditional tools to carefully remove sediments and expose the prints and record them. They make plaster casts and 3-D models of some of the tracks, though there are far too many to record them all in this way.

The team is documenting trackways as rapidly as they can, using an array of tools to locate new prints and quickly gather information from those already identified. While erosion constantly exposes new trackways, the team also searches for those that are less visible. Urban has spent most of his time in the park conducting geophysical surveys using magnetometry and ground-penetrating radar, which allow researchers to create images of tracks that lie below the surface. The team then uses traditional tools to carefully remove sediments and expose the prints and record them. They make plaster casts and 3-D models of some of the tracks, though there are far too many to record them all in this way. All around the playa, in every direction, the paths of creatures from the past preserve very specific moments. Humans ran on the balls of their feet. Families of all species—people, mammoths, camels—traveled together. There is also other evidence of ancient life lying on the surface. When Leno and Charlie visited, they immediately spotted what they thought was a grinding stone resembling those still used to smash corn or make jerky at Acoma today. “I’ve walked by here like forty times and I haven’t seen that,” says Bustos. “We’ve had geologists look at these rocks and tell us, ‘Oh no, they’re here naturally,’” adds Connelly. No one else had identified what Leno and Charlie saw.

All around the playa, in every direction, the paths of creatures from the past preserve very specific moments. Humans ran on the balls of their feet. Families of all species—people, mammoths, camels—traveled together. There is also other evidence of ancient life lying on the surface. When Leno and Charlie visited, they immediately spotted what they thought was a grinding stone resembling those still used to smash corn or make jerky at Acoma today. “I’ve walked by here like forty times and I haven’t seen that,” says Bustos. “We’ve had geologists look at these rocks and tell us, ‘Oh no, they’re here naturally,’” adds Connelly. No one else had identified what Leno and Charlie saw.

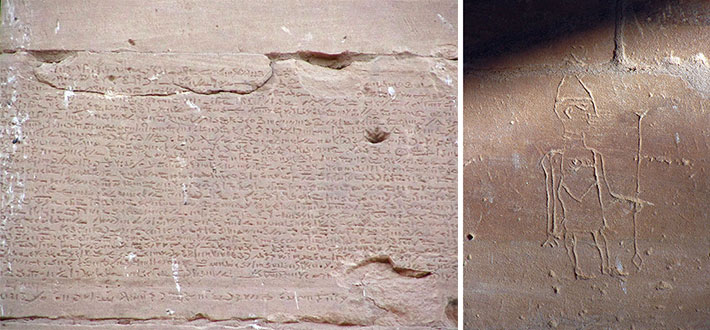

Recent research has highlighted the deep and enduring nature of this connection. Ashby has studied a corpus of ancient inscriptions recorded at Philae in the early twentieth century by British Egyptologist Francis Llewellyn Griffith and, more recently, by the late Egyptologist Eugene Cruz-Uribe of Indiana University East. Among these, she identified at least 98 inscriptions that were written on the walls of the temples at Philae on behalf of Nubians. These are mainly in the form of prayers offered to the gods. These inscriptions were written mostly in Greek and Demotic, a script used for writing ancient Egyptian, though some were also written in the Nubians’ own Meroitic script, which remains largely undeciphered. Ashby expected the inscriptions to have been commissioned by Nubian pilgrims to Philae, but she found that many were left by Nubians who had a much deeper connection to the island. “High-ranking priests, temple financial administrators, and officials were sent to Philae as representatives of the king in Meroe,” says Ashby. “Those Nubians eventually held power in the temple administration.”

Recent research has highlighted the deep and enduring nature of this connection. Ashby has studied a corpus of ancient inscriptions recorded at Philae in the early twentieth century by British Egyptologist Francis Llewellyn Griffith and, more recently, by the late Egyptologist Eugene Cruz-Uribe of Indiana University East. Among these, she identified at least 98 inscriptions that were written on the walls of the temples at Philae on behalf of Nubians. These are mainly in the form of prayers offered to the gods. These inscriptions were written mostly in Greek and Demotic, a script used for writing ancient Egyptian, though some were also written in the Nubians’ own Meroitic script, which remains largely undeciphered. Ashby expected the inscriptions to have been commissioned by Nubian pilgrims to Philae, but she found that many were left by Nubians who had a much deeper connection to the island. “High-ranking priests, temple financial administrators, and officials were sent to Philae as representatives of the king in Meroe,” says Ashby. “Those Nubians eventually held power in the temple administration.” A number of extant small temples in the forecourt of the temple of Isis that were dedicated to Nubian gods provide further evidence that Philae was significant to Nubians. One such temple was devoted to Arensnuphis, a local god of Lower Nubia who is often depicted as a desert hunter and companion of Isis, and who sometimes appears as a lion. Another small temple, in the form of a kiosk, or a colonnaded pavilion, was built at Philae during the reign of the pharaoh Nectanebo I (r. 380–362 B.C.), founder of the 30th Dynasty, the last native-born Egyptian dynasty. Cruz-Uribe proposed that the building was used as a shrine for a hybrid Nubian-Egyptian god known as Thoth Pnubs, whose name links him to the ancient Nubian city of Kerma, which was known as Pnubs to the Nubians. There was also a small temple at Philae dedicated to the Nubian deity Mandulis, a sun god associated with the nomadic people known as the Blemmyes, who lived in the deserts to the east of Egypt and Nubia. “There are all kinds of Nubian religious activities that happened before the Ptolemaic Isis temple was erected,” says Ashby.

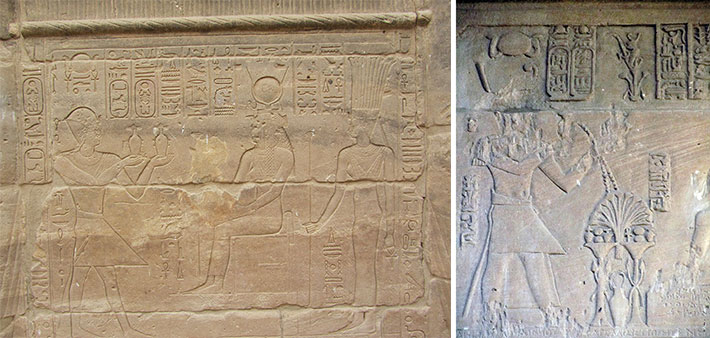

A number of extant small temples in the forecourt of the temple of Isis that were dedicated to Nubian gods provide further evidence that Philae was significant to Nubians. One such temple was devoted to Arensnuphis, a local god of Lower Nubia who is often depicted as a desert hunter and companion of Isis, and who sometimes appears as a lion. Another small temple, in the form of a kiosk, or a colonnaded pavilion, was built at Philae during the reign of the pharaoh Nectanebo I (r. 380–362 B.C.), founder of the 30th Dynasty, the last native-born Egyptian dynasty. Cruz-Uribe proposed that the building was used as a shrine for a hybrid Nubian-Egyptian god known as Thoth Pnubs, whose name links him to the ancient Nubian city of Kerma, which was known as Pnubs to the Nubians. There was also a small temple at Philae dedicated to the Nubian deity Mandulis, a sun god associated with the nomadic people known as the Blemmyes, who lived in the deserts to the east of Egypt and Nubia. “There are all kinds of Nubian religious activities that happened before the Ptolemaic Isis temple was erected,” says Ashby. Another piece of evidence linking Nubian religious practices to Philae is found on some of the massive reliefs in the island’s temples that depict Ptolemaic pharaohs and other important religious officials offering libations to gods, often Isis and Osiris and their son Horus. In Egyptian mythology, Osiris was killed and dismembered by his brother Seth. Their sister and Osiris’ wife, Isis, managed to reassemble his body and he was brought back to life as the god of the underworld. The Egyptians offered libations, usually water or wine, to Osiris during rituals intended to symbolically aid in his rebirth. At Philae, depictions of this ritual include examples that show Ptolemaic pharaohs offering Osiris water in two small bottles, as was customary in Egyptian practice. However, others appear to show them offering Osiris libations of milk, which they pour out before the god from a situla, a long narrow vessel with a looped handle. This, Ashby believes, was a distinctly Nubian practice. “What we see at these temples is this different type of libation, which is to pour out a stream of milk that goes over offerings laid out on an offering table,” she says.

Another piece of evidence linking Nubian religious practices to Philae is found on some of the massive reliefs in the island’s temples that depict Ptolemaic pharaohs and other important religious officials offering libations to gods, often Isis and Osiris and their son Horus. In Egyptian mythology, Osiris was killed and dismembered by his brother Seth. Their sister and Osiris’ wife, Isis, managed to reassemble his body and he was brought back to life as the god of the underworld. The Egyptians offered libations, usually water or wine, to Osiris during rituals intended to symbolically aid in his rebirth. At Philae, depictions of this ritual include examples that show Ptolemaic pharaohs offering Osiris water in two small bottles, as was customary in Egyptian practice. However, others appear to show them offering Osiris libations of milk, which they pour out before the god from a situla, a long narrow vessel with a looped handle. This, Ashby believes, was a distinctly Nubian practice. “What we see at these temples is this different type of libation, which is to pour out a stream of milk that goes over offerings laid out on an offering table,” she says. Hieroglyphs at Philae’s temple of Isis refer to milk as ankh-was, or “life and power.” “Milk seems to be infused with this magical element of transferring life and power to the one who is deceased, much in the way that the breast milk of a mother keeps her infant alive and growing,” says Ashby. “There seems to be this connection in the mind of Nubians.” For the Nubians, then, milk would have been the ideal offering to aid in the rebirth of Osiris.

Hieroglyphs at Philae’s temple of Isis refer to milk as ankh-was, or “life and power.” “Milk seems to be infused with this magical element of transferring life and power to the one who is deceased, much in the way that the breast milk of a mother keeps her infant alive and growing,” says Ashby. “There seems to be this connection in the mind of Nubians.” For the Nubians, then, milk would have been the ideal offering to aid in the rebirth of Osiris.

Many of the inscriptions in the most sacred spaces refer to the annual Festival of Entry celebrations that honored Osiris and Isis. While some Egyptian names do appear in references to the festival, most of the participants appear to have been Nubian, in particular members of the Wayekiye family, says Egyptologist Jeremy Pope of the College of William and Mary. “In addition to being a focus of sincere piety, theological reflection, and communal bonds,” he says, “the worship of Isis would also have been important to elite Nubian families like the Wayekiyes as an occupation, a mark of social status, and thus a source of political power.”

Many of the inscriptions in the most sacred spaces refer to the annual Festival of Entry celebrations that honored Osiris and Isis. While some Egyptian names do appear in references to the festival, most of the participants appear to have been Nubian, in particular members of the Wayekiye family, says Egyptologist Jeremy Pope of the College of William and Mary. “In addition to being a focus of sincere piety, theological reflection, and communal bonds,” he says, “the worship of Isis would also have been important to elite Nubian families like the Wayekiyes as an occupation, a mark of social status, and thus a source of political power.”

Nubian sponsorship of the temples at Philae ensured the continued survival of the worship of ancient Egyptian gods for centuries. But by the fourth century A.D., Christianity had begun to win many converts in the region. Around this time, Meroe fell to the Axum Empire, based in modern-day Ethiopia, ending Nubia’s contribution to the rites at Philae. Christians and adherents of traditional Egyptian and Nubian religions, however, continued to share the island for at least another 100 years. Ashby has found that a number of Nubian inscriptions date to this period, from about A.D. 408 to 456. These were made by priests representing the kings of the Blemmyes and included religious officials known as the prophets of Ptiris, a crocodile-like Nubian god. A Nubian family known as the Esmets served at Philae as priests for three generations, and its members eventually attained the rank of First Prophet of Isis. But the inscriptions they left were in isolated and marginal areas of the temple complex, suggesting that the priests no longer had access to the most sacred spaces. They even made inscriptions on the roof of the Isis temple, probably placed there to avoid scrutiny by Christians. One Demotic inscription, on the western wall of the temple of Isis, refers to “an abominable command,” possibly an allusion to the A.D. 435 edict of the Roman emperor Theodosius II (r. A.D. 408–450) that called for the destruction of all pagan temples in the empire. The last Demotic inscription was written in A.D. 452 on the roof of the temple of Isis, and the last pagan Greek inscription was made in A.D. 456.

Nubian sponsorship of the temples at Philae ensured the continued survival of the worship of ancient Egyptian gods for centuries. But by the fourth century A.D., Christianity had begun to win many converts in the region. Around this time, Meroe fell to the Axum Empire, based in modern-day Ethiopia, ending Nubia’s contribution to the rites at Philae. Christians and adherents of traditional Egyptian and Nubian religions, however, continued to share the island for at least another 100 years. Ashby has found that a number of Nubian inscriptions date to this period, from about A.D. 408 to 456. These were made by priests representing the kings of the Blemmyes and included religious officials known as the prophets of Ptiris, a crocodile-like Nubian god. A Nubian family known as the Esmets served at Philae as priests for three generations, and its members eventually attained the rank of First Prophet of Isis. But the inscriptions they left were in isolated and marginal areas of the temple complex, suggesting that the priests no longer had access to the most sacred spaces. They even made inscriptions on the roof of the Isis temple, probably placed there to avoid scrutiny by Christians. One Demotic inscription, on the western wall of the temple of Isis, refers to “an abominable command,” possibly an allusion to the A.D. 435 edict of the Roman emperor Theodosius II (r. A.D. 408–450) that called for the destruction of all pagan temples in the empire. The last Demotic inscription was written in A.D. 452 on the roof of the temple of Isis, and the last pagan Greek inscription was made in A.D. 456.