Digs & Discoveries

Typing Time

By HYUNG-EUN KIM

Tuesday, October 12, 2021

About 1,600 blocks of metal movable type from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries have been discovered inside an earthenware pot underneath Jongno, one of Seoul’s busiest tourist districts. This is the largest collection of movable type blocks from the period ever discovered in Korea. Six hundred of the pieces use hangul, the Korean alphabet, which was created in 1433 and gradually replaced Chinese characters.

About 1,600 blocks of metal movable type from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries have been discovered inside an earthenware pot underneath Jongno, one of Seoul’s busiest tourist districts. This is the largest collection of movable type blocks from the period ever discovered in Korea. Six hundred of the pieces use hangul, the Korean alphabet, which was created in 1433 and gradually replaced Chinese characters.

The earliest known examples of hangul metal movable type are 30 pieces held by the National Museum of Korea, dating to 1455, that were used by Korean royalty. Researchers believe the new finds date from around the same time. The blocks were found with other metal objects that commoners would normally not have had access to, including artillery and parts of an astronomical clock and a water clock—both of which are described in royal documents.

During the Joseon period (1392–1910), the Jongno area of Seoul was one of the city’s most prosperous financial and commercial districts, as well as home to government officials and wealthy merchants. Archaeologists believe the site where the type blocks were found was likely a house’s storage room, and that the blocks were buried with the intention of reusing them later. This may have been a response to an unexpected event, such as the Japanese invasion known as the Imjin War (1592–1598).

In Full Color

By DANIEL WEISS

Tuesday, October 12, 2021

An unusual painted sculpture of a woman covered in jewels and seated on a throne dating to the fourth century B.C. was unearthed in a tomb in the southern Spanish city of Baza in 1971. As soon as it was out of the ground, the sculpture’s colors began to fade. At the time, archaeologist Francisco Presedo attempted to preserve the colors by coating the sculpture in hair spray. Later, more scientific conservation methods were applied. Now, a team of researchers led by Teresa Chapa Brunet of the Complutense University of Madrid has employed digital photographic techniques to capture the original colors of the Lady of Baza, as the sculpture is known. By using polarizing filters, which eliminate almost all reflected light, they have revealed that the sculpture appears to represent an Iberian woman wearing clothing typical of the period, with lifelike skin tones and even a double chin. Chapa Brunet notes that other Iberian sculptures from the time tend to be more idealized and stylized. “This is the only Iberian stone sculpture to have been found in a tomb, which suggests it was intended for a private rather than a public context,” she says. “This could explain the realism of its features.”

An unusual painted sculpture of a woman covered in jewels and seated on a throne dating to the fourth century B.C. was unearthed in a tomb in the southern Spanish city of Baza in 1971. As soon as it was out of the ground, the sculpture’s colors began to fade. At the time, archaeologist Francisco Presedo attempted to preserve the colors by coating the sculpture in hair spray. Later, more scientific conservation methods were applied. Now, a team of researchers led by Teresa Chapa Brunet of the Complutense University of Madrid has employed digital photographic techniques to capture the original colors of the Lady of Baza, as the sculpture is known. By using polarizing filters, which eliminate almost all reflected light, they have revealed that the sculpture appears to represent an Iberian woman wearing clothing typical of the period, with lifelike skin tones and even a double chin. Chapa Brunet notes that other Iberian sculptures from the time tend to be more idealized and stylized. “This is the only Iberian stone sculpture to have been found in a tomb, which suggests it was intended for a private rather than a public context,” she says. “This could explain the realism of its features.”

Identifying the Unidentified

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Tuesday, October 12, 2021

From its heart in Italy across its many thousands of miles, the Roman Empire was built and maintained by slaves. Some were born enslaved, the sons and daughters of enslaved mothers. Others were captives subjugated by the Roman army. Still others were bought and sold at slave markets. Slaves toiled in all arenas of the Roman world, including homes, schools, fields, mines, construction projects, and even entertainment. A few, including the former gladiator Spartacus, even led rebellions against Rome.

From its heart in Italy across its many thousands of miles, the Roman Empire was built and maintained by slaves. Some were born enslaved, the sons and daughters of enslaved mothers. Others were captives subjugated by the Roman army. Still others were bought and sold at slave markets. Slaves toiled in all arenas of the Roman world, including homes, schools, fields, mines, construction projects, and even entertainment. A few, including the former gladiator Spartacus, even led rebellions against Rome.

Yet Roman slaves are nearly invisible in the archaeological record. They had few if any possessions, are rarely identified in texts, and their burials are seldom marked with a gravestone. “Slavery is a profound part of the Roman world and completely endemic,” says archaeologist Michael Marshall of Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA). “But especially for Roman Britain, people have avoided talking about or investigating it because of the lack of texts and the complexity of the issue of slavery.” A unique burial discovered in central England’s Midlands region may be the first step to changing that.

Yet Roman slaves are nearly invisible in the archaeological record. They had few if any possessions, are rarely identified in texts, and their burials are seldom marked with a gravestone. “Slavery is a profound part of the Roman world and completely endemic,” says archaeologist Michael Marshall of Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA). “But especially for Roman Britain, people have avoided talking about or investigating it because of the lack of texts and the complexity of the issue of slavery.” A unique burial discovered in central England’s Midlands region may be the first step to changing that.

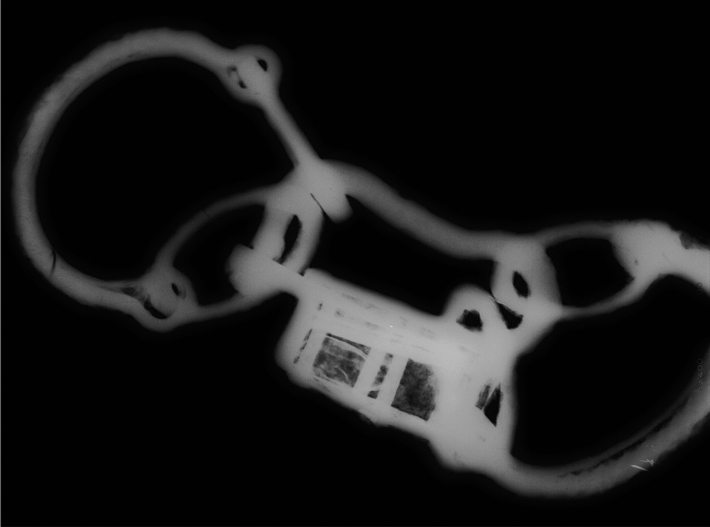

Several years ago, during work on a greenhouse at a home in the village of Great Casterton, builders unearthed an adult male skeleton, which was then excavated by a MOLA team. The man was lying on his right side and had heavy iron fetters secured by a padlock around his ankles. His remains were radiocarbon dated to between A.D. 226 and 427, a period during which, until the very last years, the Romans occupied Britain. Earlier excavations about 200 feet away had revealed a well-planned third- to fourth-century A.D. cemetery filled with 133 burials, at least some in wooden coffins. The man’s skeleton, however, had been tossed into a ditch at the time of his death between the ages of 26 and 35. His twisted body, the unnatural position of his left arm over his head, and the absence of scavenging animals’ tooth marks—which likely would have been visible on his bones had his body been exposed for any length of time—all suggested the man was buried quickly and with little care. Although his skeleton is well preserved, indicating he was five feet five inches tall—average for the period—his head is missing, likely an accidental casualty of modern construction work. Marshall and MOLA osteoarchaeologist Chris Chinnock immediately wondered if the man had been a slave, which would make him the first Roman slave to be archaeologically excavated in Britain. But in the absence of a clear methodology for recognizing Roman slavery in the archaeological record, how would they know?

“The suggestion of slavery, punishment, or something nefarious immediately leapt to mind,” says Chinnock. Despite the fetters’ dramatic appearance, they do not definitively prove that the man was enslaved. This type of shackle has rarely been found anywhere in the Roman world, and never in Roman Britain. When Chinnock examined the skeleton to reconstruct the man’s life based on his bones, creating what scholars call an osteobiography, he found some lesions on his ankles and tibias from infections or trauma, but nothing that conclusively linked them to the fetters. He also found a bony spur on the man’s left femur. “The spur is of a type that can occur from a traumatic injury or from the repetitive activities of an active lifestyle, hard labor, or even heavy contact sports,” says Chinnock. “Nothing screams that this person was enslaved.” Furthermore, the man was buried near a thriving Roman town, and there would have been both slaves and laborers in the surrounding fields, farms, and villages.

“The suggestion of slavery, punishment, or something nefarious immediately leapt to mind,” says Chinnock. Despite the fetters’ dramatic appearance, they do not definitively prove that the man was enslaved. This type of shackle has rarely been found anywhere in the Roman world, and never in Roman Britain. When Chinnock examined the skeleton to reconstruct the man’s life based on his bones, creating what scholars call an osteobiography, he found some lesions on his ankles and tibias from infections or trauma, but nothing that conclusively linked them to the fetters. He also found a bony spur on the man’s left femur. “The spur is of a type that can occur from a traumatic injury or from the repetitive activities of an active lifestyle, hard labor, or even heavy contact sports,” says Chinnock. “Nothing screams that this person was enslaved.” Furthermore, the man was buried near a thriving Roman town, and there would have been both slaves and laborers in the surrounding fields, farms, and villages.

Still, says Marshall, the Great Casterton burial is “about the best evidence you could have for the social phenomenon of slavery.” “We don’t see the physical evidence of enslavement very often, so it evokes an immediate response,” says Chinnock. “This was an actual person, and he is valuable as an individual.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

When Isis Was Queen

Italian Master Builders

Ghost Tracks of White Sands

Piecing Together Maya Creation Stories

Gaul's University Town

Letter from Ghana

Digs & Discoveries

Identifying the Unidentified

In Full Color

Typing Time

Otto's Church

An Irish Idol

A Family's Final Resting Place

A Place of Their Own

A Trip to Venice

Salty Snack

The Age of Glass

China's New Human Species

Mesopotamian War Memorial

Off the Grid

Around the World

Under the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, Ice Age camping in Michigan, and a Mesolithic Russian amber merchant

Artifact

Lost in translation

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement