Digs & Discoveries

Russian River Silver

By DANIEL WEISS

Friday, December 03, 2021

Several dozen silver artifacts have been discovered on a forested riverbank in the vicinity of Old Ryazan in southwestern Russia. This new find joins a number of other treasure hoards previously unearthed in the area that were stowed away in advance of a 1237 invasion by the Mongols. However, based on the style of the jewelry in this hoard—which includes 14 bracelets, eight torcs, five rings, and a bead, as well as four hryvnias, or silver ingots used as money—researchers believe it dates to the late eleventh or early twelfth century.

Several dozen silver artifacts have been discovered on a forested riverbank in the vicinity of Old Ryazan in southwestern Russia. This new find joins a number of other treasure hoards previously unearthed in the area that were stowed away in advance of a 1237 invasion by the Mongols. However, based on the style of the jewelry in this hoard—which includes 14 bracelets, eight torcs, five rings, and a bead, as well as four hryvnias, or silver ingots used as money—researchers believe it dates to the late eleventh or early twelfth century.

At that time, there were no settlements close by, though a road that led from the city of Old Ryazan, which was a major trading site, passed within a half mile or so. According to Igor Strikalov, an archaeologist at the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Archaeology, the hoard was likely the accumulated wealth of a merchant—or a thief. It contains nearly five pounds of silver, which by weight alone would have been sufficient to buy 10 warhorses or more than 200 sheep. “Perhaps the owner hid the treasure out of fear,” says Strikalov. “The fears were justified: He could not return for the treasure, since he probably died soon after.”

Burn Notice

By MARLEY BROWN

Friday, December 03, 2021

While installing lights in front of Memorial Church, a 1907 structure that stands on the site of a timber frame church first constructed at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1617, archaeologists uncovered a layer of charcoal and fire-reddened earth. They have now determined that this is evidence of a blaze that consumed the church on September 19, 1676, during Bacon’s Rebellion. As part of this uprising against the Virginia colonial government led by wealthy landowner Nathaniel Bacon, Virginians of all social classes demanded the right to expand into territory that was already inhabited by Native Americans, violated treaties with Native groups, and set fire to Jamestown, which was the colony’s capital.

While installing lights in front of Memorial Church, a 1907 structure that stands on the site of a timber frame church first constructed at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1617, archaeologists uncovered a layer of charcoal and fire-reddened earth. They have now determined that this is evidence of a blaze that consumed the church on September 19, 1676, during Bacon’s Rebellion. As part of this uprising against the Virginia colonial government led by wealthy landowner Nathaniel Bacon, Virginians of all social classes demanded the right to expand into territory that was already inhabited by Native Americans, violated treaties with Native groups, and set fire to Jamestown, which was the colony’s capital.

While other fires are known to have caused damage at Jamestown during the Revolutionary War and the Civil War, Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologist Sean Romo is certain that artifacts uncovered at the site just above the burn layer date this fire to the period of Bacon’s Rebellion. These include a section of window lead dating to 1678 and fragments of ceramics made by local potter Morgan Jones, who was only active in 1677. “Everything immediately under the modern pathway and right above the burned layer was found still intact from the late 1600s,” says Romo.

Tamil Royal Palace

By GURVINDER SINGH

Friday, December 03, 2021

Archaeologists in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu have unearthed brick structures in the town of Maligaimedu that are thought to be traces of the Chola Empire, which ruled the region around 1,000 years ago. “We believe the remains to be the palace of the Chola kings,” says R. Sivanantham, director of the Tamil Nadu archaeology department. He adds that the palace was likely built by King Rajendra Chola (r. ca. 1014–1044), who established the site as the Chola capital in 1025. The researchers have uncovered building foundations, a Chola period copper coin, glass beads, and bangles. They have also found a range of ceramics, including Chinese ware that provides evidence of a long-distance trade network.

Archaeologists in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu have unearthed brick structures in the town of Maligaimedu that are thought to be traces of the Chola Empire, which ruled the region around 1,000 years ago. “We believe the remains to be the palace of the Chola kings,” says R. Sivanantham, director of the Tamil Nadu archaeology department. He adds that the palace was likely built by King Rajendra Chola (r. ca. 1014–1044), who established the site as the Chola capital in 1025. The researchers have uncovered building foundations, a Chola period copper coin, glass beads, and bangles. They have also found a range of ceramics, including Chinese ware that provides evidence of a long-distance trade network.

Cave Fit for a King...or a Hermit

By DANIEL WEISS

Friday, December 03, 2021

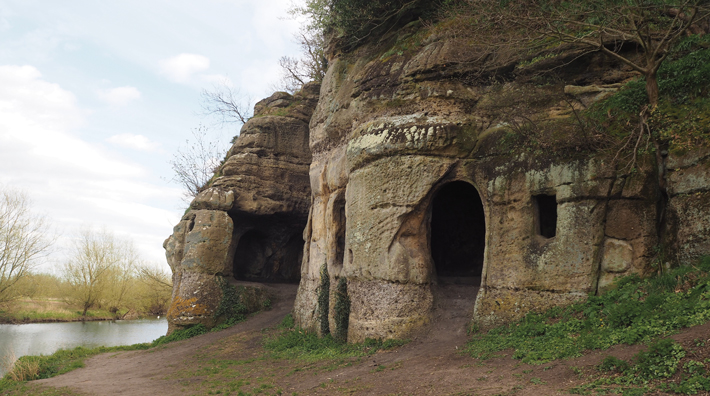

A cave carved by human hands out of a sandstone cliff above a tributary of the River Trent in Derbyshire, England, may have been occupied as early as the seventh century A.D. Edmund Simons, an archaeologist at the Royal Agricultural University, recently led a team that found that the Romanesque doors of the three-room cave are very similar to those found in other medieval buildings. Moreover, a rock-cut pillar in the cave is of a style found in many Anglo-Saxon structures, including a seventh-century A.D. crypt in nearby Repton. This raises the possibility that the cave may have been built to imitate the crypt, or possibly even by the same architect.

A cave carved by human hands out of a sandstone cliff above a tributary of the River Trent in Derbyshire, England, may have been occupied as early as the seventh century A.D. Edmund Simons, an archaeologist at the Royal Agricultural University, recently led a team that found that the Romanesque doors of the three-room cave are very similar to those found in other medieval buildings. Moreover, a rock-cut pillar in the cave is of a style found in many Anglo-Saxon structures, including a seventh-century A.D. crypt in nearby Repton. This raises the possibility that the cave may have been built to imitate the crypt, or possibly even by the same architect.

Legend holds the cave was once inhabited by a ninth-century A.D. saint named Hardulph, who has been identified with Eardwulf, a deposed king of Northumbria who lived out his final years exiled in the early medieval Kingdom of Mercia, where the cave is located. Likewise, its name, Anchor Church, which dates to at least the thirteenth century, suggests the cave was home to anchorites, or religious hermits. “Saint Hardulph has a cell in a cliff a little from the Trent,” reports a fragment of a medieval book preserved in a 1545 volume. “Anchor Church is the only real contender because there aren’t any other caves by the Trent that are like it in that area,” says Simons. The cave went on to be used in the eighteenth century by inhabitants of the nearby manor house, Foremarke Hall, as an entertainment venue. Archaeologists have found evidence that the gentlefolk knocked out some of the cave’s walls to provide an airier space with better views of the valley below.

The Roots of Violence

By ANDREW CURRY

Friday, December 03, 2021

In the early 1960s, archaeologists from around the world descended on the Upper Nile Valley. They were scrambling to excavate ahead of the construction of the Aswan High Dam, which would submerge dozens of archaeological sites, including a 13,400-year-old cemetery called Jebel Sahaba, by the decade’s end. The cemetery, in what is now northern Sudan, was found to contain the skeletons of 61 men, women, and children. While excavating their remains, the late archaeologist Fred Wendorf of Southern Methodist University noticed unmistakable signs of violence—broken bones, smashed skulls, and stone projectiles embedded in the people’s bones or lying near their bodies. He concluded that they were victims of a battle or massacre. At the time, the idea of organized warfare in the distant past was revolutionary. “Prevailing archaeological doctrine in the peace-and-love era of the 1960s held that war and violence were modern inventions,” says Christopher Knüsel, a physical anthropologist at the University of Bordeaux. “There was a long period when archaeologists said warfare didn’t happen in prehistory.”

In the early 1960s, archaeologists from around the world descended on the Upper Nile Valley. They were scrambling to excavate ahead of the construction of the Aswan High Dam, which would submerge dozens of archaeological sites, including a 13,400-year-old cemetery called Jebel Sahaba, by the decade’s end. The cemetery, in what is now northern Sudan, was found to contain the skeletons of 61 men, women, and children. While excavating their remains, the late archaeologist Fred Wendorf of Southern Methodist University noticed unmistakable signs of violence—broken bones, smashed skulls, and stone projectiles embedded in the people’s bones or lying near their bodies. He concluded that they were victims of a battle or massacre. At the time, the idea of organized warfare in the distant past was revolutionary. “Prevailing archaeological doctrine in the peace-and-love era of the 1960s held that war and violence were modern inventions,” says Christopher Knüsel, a physical anthropologist at the University of Bordeaux. “There was a long period when archaeologists said warfare didn’t happen in prehistory.”

For decades after their discovery, scholars pointed to the skeletons of Jebel Sahaba as the earliest evidence of violence, and even warfare, in deep prehistory. But at the time of the dig, the science of physical anthropology—the investigation of human bones for clues to how people lived and died—was in its infancy, and no comprehensive analysis of the remains was undertaken.

For decades after their discovery, scholars pointed to the skeletons of Jebel Sahaba as the earliest evidence of violence, and even warfare, in deep prehistory. But at the time of the dig, the science of physical anthropology—the investigation of human bones for clues to how people lived and died—was in its infancy, and no comprehensive analysis of the remains was undertaken.

Fifty years after the original excavation, in 2014, Isabelle Crevecoeur, an archaeologist with the French National Center for Scientific Research, began investigating the causes of the millennia-long shift from hunting and gathering to herding and farming in the Nile Valley. She thought one way to shed light on this question might be to reexamine the bones from Jebel Sahaba, now housed in the British Museum. “There was a lot of fantasy around this cemetery,” Crevecoeur says. She and a team of physical anthropologists examined each skeleton and identified more than 100 previously undiscovered signs of trauma or violence, including evidence of arrow strikes. “Methods have really advanced, especially the way we look at cut marks and trauma,” says Daniel Antoine, curator of bioarchaeology at the British Museum. Until recently, researchers weren’t even certain what arrow strikes look like on bone, but new 3-D imaging techniques have made it possible to identify them.

The team’s findings suggest that the cemetery wasn’t a mass grave resulting from a single battle, but something perhaps grimmer: evidence of decades of continual violence among neighboring groups in the form of frequent raids, sneak attacks, and ambushes. Crevecoeur identified numerous skeletons with both healed and unhealed wounds—people who had survived one violent encounter, only to be slain months or years later. On a battlefield, the dead are mostly people in the prime of their lives—for example, young men defending their village. But the Jebel Sahaba skeletons belong mostly to the very young and very old. Crevecoeur suggests that young, healthy people are absent because they would have been more likely to survive an ambush, escape an attack, or recover from their wounds. Equally grim are the individual wounds, including fractured hands and forearms perhaps incurred as people died trying to ward off blows. Some skeletons have evidence of arrow strikes and blows to their backs, as though the people had been struck down while attempting to flee.

When their analysis was complete, the team found that more than 60 percent of the skeletons had visible signs of trauma. “That’s off the scale,” says Knüsel. “This suggests there’s something really unusual happening.” Crevecoeur thinks she knows what. Around 13,000 years ago, the once-lush Nile Valley began to dry up. Within a few millennia, it was essentially a desert oasis hundreds of miles long. For the first time, people living along the river had to compete for resources. “It’s not difficult to imagine a long-lasting climate of tension between groups,” Crevecoeur says. Her findings echo discoveries elsewhere in the world that suggest violence was far more common in prehistory than once thought. “Science is constantly evolving, and these multiple violent events highlight that violence’s cause is more complex than a single battle,” says Antoine. “As long as we curate the dead with care, respect, and dignity, these bodies are windows into the past other sources can’t address.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Digs & Discoveries

The Roots of Violence

Tamil Royal Palace

Cave Fit for a King...or a Hermit

Burn Notice

Russian River Silver

New Neighbors

Viking Roles

A Ride Through the Countryside

Japan's Genetic History

Off the Grid

Around the World

Uncovering a whisky distillery, the first Azoreans, Chinese mummy genetics, and an ancient hangover cure

Artifact

Opener to interpretation

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement