Features

Exploring Notre Dame's Hidden Past

By CHRISTINE FINN

Friday, April 07, 2023

The first major fire at Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral burned through an August night more than 800 years ago. At the time, cathedral fires were not uncommon—the structures were tinderboxes of dry wood, textiles, hanging lamps, and burning candles. The twelfth-century chronicler Guillaume le Breton records that the inferno started when a thief broke into the cathedral’s attic and, using ropes and hooks in an attempt to steal the candlesticks, set the silk hangings alight. Over the following centuries, there were almost certainly many more fires, but none as catastrophic as the one that began in the attic and engulfed the building on April 15, 2019. The cause of that conflagration remains uncertain; an electrical short circuit or damaged electrical cable in use during restoration efforts taking place at the time are the possible culprits.

The first major fire at Paris’ Notre Dame Cathedral burned through an August night more than 800 years ago. At the time, cathedral fires were not uncommon—the structures were tinderboxes of dry wood, textiles, hanging lamps, and burning candles. The twelfth-century chronicler Guillaume le Breton records that the inferno started when a thief broke into the cathedral’s attic and, using ropes and hooks in an attempt to steal the candlesticks, set the silk hangings alight. Over the following centuries, there were almost certainly many more fires, but none as catastrophic as the one that began in the attic and engulfed the building on April 15, 2019. The cause of that conflagration remains uncertain; an electrical short circuit or damaged electrical cable in use during restoration efforts taking place at the time are the possible culprits.

For 15 hours, flames reaching nearly 1,200°F ate away at a large part of the cathedral’s medieval wooden roof, which crashed onto the stone vaulting that forms its ceiling. The nineteenth-century spire that topped the building broke apart when the lead coating meant to protect it melted. The weight of the debris caused a ceiling vault to collapse, sending huge piles of burned wood and broken stone down to the marble floor of the nave. When the fire was finally extinguished, the scene was one of complete devastation and the atmosphere one of extreme concern. Parisians, along with those watching from around the world, wondered if the building was structurally sound, if the cathedral’s spectacular stained-glass windows had survived, and if Notre Dame, which has been called the soul of the city—and of France—could ever be rebuilt.

For 15 hours, flames reaching nearly 1,200°F ate away at a large part of the cathedral’s medieval wooden roof, which crashed onto the stone vaulting that forms its ceiling. The nineteenth-century spire that topped the building broke apart when the lead coating meant to protect it melted. The weight of the debris caused a ceiling vault to collapse, sending huge piles of burned wood and broken stone down to the marble floor of the nave. When the fire was finally extinguished, the scene was one of complete devastation and the atmosphere one of extreme concern. Parisians, along with those watching from around the world, wondered if the building was structurally sound, if the cathedral’s spectacular stained-glass windows had survived, and if Notre Dame, which has been called the soul of the city—and of France—could ever be rebuilt.

The fire pared Notre Dame to its core, but the destruction is providing an unprecedented chance for scholars to investigate its history and reimagine its future. For archaeologists, the bent iron, burned roof timbers, and shattered stonework provide an opportunity to study a building that, despite its religious, architectural, and historic significance, is, in fact, poorly understood. Over time, the cathedral was modified to accommodate the requirements of a growing staff of clergy and an expanding congregation, as well as the increasing number of visitors to a building not designed for mass tourism, obscuring its medieval origins. Since the nineteenth-century renovation by architect Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc, there has been little opportunity to study the cathedral’s archaeological record.

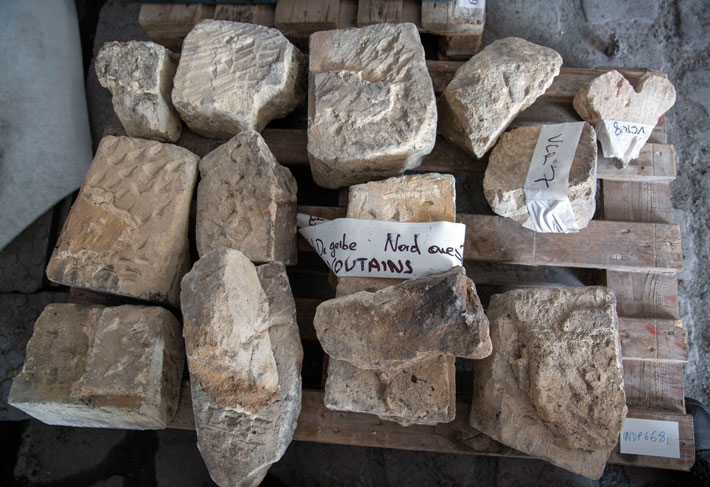

Archaeologists and other specialists removed, sorted, and inventoried the collapsed remains from late April 2019 to spring 2021, after which the artifacts were transferred to rented warehouses in the northeast of Paris where they are available for study. What researchers have collected is considerable—about 10,000 pieces of wood, 650 pallets of stone, and 350 pallets of metal. “It’s impressive to have Notre Dame right there in front of us,” says archaeologist Dorothée Chaoui-Derieux of the French Ministry of Culture. “There is a certain emotion to have at hand blocks of stone that were previously more than 100 feet up and about which little was known, or all this wood, some of which dates to the thirteenth century and still smells like burning from the fire.”

|

Sidebar:

|

Layers of History

|

Paradise Lost

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, April 11, 2022

Starting in the early seventeenth century, the French began settling the colony of Acadia—which stretched across what is now Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and south into Maine—where they established a number of prosperous agricultural communities. A key to their success was a system of dikes they created, particularly in Nova Scotia, that allowed water to drain out of the marshes but prevented seawater from flowing back in. Once rain washed the salt away from this reclaimed land, it became extremely fertile thanks to the rich organic material that had been deposited by the tides over thousands of years. The great quantity of peas, wheat, and other grains, as well as livestock, which the Acadians consumed and exported, helped fuel population growth that is among the fastest ever recorded in human history, up to 4.5 percent per year. Between 1710 and 1730, the Acadian population doubled and then doubled again by 1755, when it reached around 14,000. The Acadians’ ambitious land reclamation project reached its apogee at Grand Pré, or “great meadow,” a village founded by a group of extended families around 1682. Grand Pré overlooked a vast expanse of marshland abutting the Minas Basin, home to the highest tides in the world, which can rise more than 50 feet. The Acadians’ expertise allowed them to tame the tides and transform this salt marsh into robust farmland.

Starting in the early seventeenth century, the French began settling the colony of Acadia—which stretched across what is now Prince Edward Island, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and south into Maine—where they established a number of prosperous agricultural communities. A key to their success was a system of dikes they created, particularly in Nova Scotia, that allowed water to drain out of the marshes but prevented seawater from flowing back in. Once rain washed the salt away from this reclaimed land, it became extremely fertile thanks to the rich organic material that had been deposited by the tides over thousands of years. The great quantity of peas, wheat, and other grains, as well as livestock, which the Acadians consumed and exported, helped fuel population growth that is among the fastest ever recorded in human history, up to 4.5 percent per year. Between 1710 and 1730, the Acadian population doubled and then doubled again by 1755, when it reached around 14,000. The Acadians’ ambitious land reclamation project reached its apogee at Grand Pré, or “great meadow,” a village founded by a group of extended families around 1682. Grand Pré overlooked a vast expanse of marshland abutting the Minas Basin, home to the highest tides in the world, which can rise more than 50 feet. The Acadians’ expertise allowed them to tame the tides and transform this salt marsh into robust farmland.

In part because they created their own agricultural land, the Acadians had friendly, collaborative relationships with the Indigenous Mi’kmaq. In a place with such plenty, there was no need to compete for resources. There were even a significant number of marriages between the groups, which was unheard of in the New England colonies to the south, where Native peoples and Europeans were, at best, wary of each other. Heavily influenced by the Mi’kmaq, the Acadians developed a social structure based on communal cooperation that contrasted starkly with the rigid hierarchy they had known in France. This communal spirit was particularly helpful in organizing and carrying out the hard labor necessary to build and maintain the monumental dikes that held back the tides. “In France, if you were a peasant, you were under a nobleman’s control and had no real freedom,” says Rob Ferguson, a retired Parks Canada archaeologist. “When the colonists came to Acadia, they suddenly had control of their own lives. They had their own farms and they could sell their crops. There was intermarrying between levels of society that would never have happened in France. In a way, they really did have a paradise.”

In part because they created their own agricultural land, the Acadians had friendly, collaborative relationships with the Indigenous Mi’kmaq. In a place with such plenty, there was no need to compete for resources. There were even a significant number of marriages between the groups, which was unheard of in the New England colonies to the south, where Native peoples and Europeans were, at best, wary of each other. Heavily influenced by the Mi’kmaq, the Acadians developed a social structure based on communal cooperation that contrasted starkly with the rigid hierarchy they had known in France. This communal spirit was particularly helpful in organizing and carrying out the hard labor necessary to build and maintain the monumental dikes that held back the tides. “In France, if you were a peasant, you were under a nobleman’s control and had no real freedom,” says Rob Ferguson, a retired Parks Canada archaeologist. “When the colonists came to Acadia, they suddenly had control of their own lives. They had their own farms and they could sell their crops. There was intermarrying between levels of society that would never have happened in France. In a way, they really did have a paradise.”

Regardless of their successes, the Acadians were repeatedly caught up in the geopolitical rivalry between France and Britain, with control of Nova Scotia passing back and forth between the two empires multiple times. The Acadians endeavored to remain neutral, resisting attempts by both sides to win their fealty. They cultivated profitable trade relations with New England merchants, whom at least one source records they dubbed nos amis les ennemis, or “our friends the enemy.” Over time, the Acadians came to see themselves as an independent creole people, native to their new land and no longer bound to their home country. They would raise the French or English flag depending on whose gunships were coming to pay a visit. When the British took control of Nova Scotia for good in 1713, the French tried to entice the Acadians to move to Île Royale, modern-day Cape Breton Island, but most remained where they were, reasoning that the British were more likely to leave them alone. They were mistaken, however, and their position grew increasingly precarious. Suspicious of the Acadians because they were Catholic and friendly with the Mi’kmaq, British representatives pressured them to pledge an unconditional oath of allegiance to the Crown. The Acadians managed to fend off their demands for several decades, in no small measure because local British forces depended on their crops for sustenance.

|

Sidebar:

|

From Acadian to Cajun

|

A Monumental Imperial Biography

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Thursday, February 10, 2022

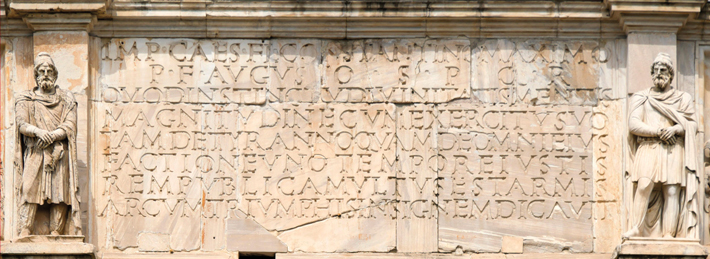

For the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantine the Greatest, pious blessed Augustus, because by inspiration of divinity, in greatness of his mind, from a tyrant on one side and from every faction of all on the other side at once, with his army he avenged the republic with just arms, the Senate and Roman People (SPQR) dedicated this arch as a sign for his triumphs.—Dedicatory inscription, Arch of Constantine, Rome

For the Emperor Caesar Flavius Constantine the Greatest, pious blessed Augustus, because by inspiration of divinity, in greatness of his mind, from a tyrant on one side and from every faction of all on the other side at once, with his army he avenged the republic with just arms, the Senate and Roman People (SPQR) dedicated this arch as a sign for his triumphs.—Dedicatory inscription, Arch of Constantine, Rome

The pinnacle of an ancient Roman general’s or emperor’s military career was to be awarded the right to parade through the streets of Rome to celebrate his victories on the battlefield and flaunt the spoils of war in an extravagant display known as a triumph. During these grand spectacles, Romans watched as senators clad in brilliant white togas trimmed in purple made their way through crowded, noisy streets, followed by trumpeters and scores of other musicians, bulls to be slaughtered for feasts, and exotic animals captured in far-off conquered lands. Shackled prisoners, many of whom would later be executed, were hauled through the city, and heaping mounds of booty—gold and silver, marble statues, and more—were piled high on wagons pulled by draft animals. People craned their necks as the victorious general rode by in a four-horse chariot covered in laurel, the symbol of victory, holding a scepter and wearing a purple tunic, a decorated gold toga, a laurel wreath, and a gold crown. He was followed by his troops, whom ancient sources describe as singing loudly and shouting victory chants. Celebrating great military victories did not always end there. On occasion, the Senate also voted to build a monumental arch to celebrate the commander’s conquests. There were once 57 triumphal arches in Rome and more across the empire. Yet little is known about the vast majority of these monuments from contemporaneous or later sources, and no remains of them survive. Only three of the city’s triumphal arches still exist, the largest of which is the Arch of Constantine.

The pinnacle of an ancient Roman general’s or emperor’s military career was to be awarded the right to parade through the streets of Rome to celebrate his victories on the battlefield and flaunt the spoils of war in an extravagant display known as a triumph. During these grand spectacles, Romans watched as senators clad in brilliant white togas trimmed in purple made their way through crowded, noisy streets, followed by trumpeters and scores of other musicians, bulls to be slaughtered for feasts, and exotic animals captured in far-off conquered lands. Shackled prisoners, many of whom would later be executed, were hauled through the city, and heaping mounds of booty—gold and silver, marble statues, and more—were piled high on wagons pulled by draft animals. People craned their necks as the victorious general rode by in a four-horse chariot covered in laurel, the symbol of victory, holding a scepter and wearing a purple tunic, a decorated gold toga, a laurel wreath, and a gold crown. He was followed by his troops, whom ancient sources describe as singing loudly and shouting victory chants. Celebrating great military victories did not always end there. On occasion, the Senate also voted to build a monumental arch to celebrate the commander’s conquests. There were once 57 triumphal arches in Rome and more across the empire. Yet little is known about the vast majority of these monuments from contemporaneous or later sources, and no remains of them survive. Only three of the city’s triumphal arches still exist, the largest of which is the Arch of Constantine.

The arch celebrates the emperor Constantine’s (r. A.D. 306–337) victory over the usurper Maxentius (r. A.D. 306–312) at the Milvian Bridge just outside Rome on October 28, A.D. 312. For six years, the two had reigned as co-emperors. This battle brought an end to nearly a century of civil war and cemented Constantine’s place as the sole ruler of the Western Roman Empire. Sole rulership of the Eastern Empire would come 12 years later, at which time he became the ruler of the entire empire. The monument rises 69 feet high and measures 85 feet wide, and its decorations represent three centuries of imperial history. It has long been clear to scholars that much of the arch’s sculpture came from monuments dedicated to the earlier emperors Trajan (r. A.D. 98–117), Hadrian (r. A.D. 117–138), and Marcus Aurelius (r. A.D. 161–180). Other decorative elements of the arch were created at the time it was built. These include the dedicatory inscription along the top of both sides of the structure, as well as the winged victory figures flanking the central passageway and several reliefs inside the central passageway, some of which depict the sun god, Sol. The monument was topped by a gilded bronze statue of the emperor in his chariot.

The Last King of Babylon

By ERIC A. POWELL

Sunday, March 13, 2022

The fall of an empire in antiquity was usually the result of complex, interconnected factors that lay beyond the scope of any one person’s control. Nonetheless, traumatized contemporaries and later historians alike have often laid the fault at the feet of a single individual. “It’s the last ruler who is usually blamed for an empire’s downfall,” says University of Toronto Assyriologist Paul-Alain Beaulieu. The enigmatic Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus seemed destined for just such a fate after the Persian armies of Cyrus the Great marched through Babylon’s gates in October 539 B.C. By deposing Nabonidus, whose reign was marked by eccentric political and religious choices, the Persians ensured that he would be the last ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539 B.C.) and the last native-born Mesopotamian king. For some 2,500 years, Mesopotamian cities, states, and empires had been ruled by their own, or by outsiders who adopted their ways. But after Nabonidus (r. 556–539 B.C.), the region was conquered by a series of foreign empires before Mesopotamia’s great ancient cities such as Ur, Uruk, and Babylon finally withered away. Many sources from antiquity cast Nabonidus as the villain who brought about the downfall of Babylon, and by extension, Mesopotamia. “He was a controversial figure,” says Beaulieu, “and perhaps a tragic one.” Today, some scholars believe that, despite being variously portrayed in ancient texts as a mad usurper and a heretic whose apostasy doomed an empire, Nabonidus may, in fact, have simply been a difficult personality with a singular political vision whose reign was cut short before he could realize his ambitions.

The fall of an empire in antiquity was usually the result of complex, interconnected factors that lay beyond the scope of any one person’s control. Nonetheless, traumatized contemporaries and later historians alike have often laid the fault at the feet of a single individual. “It’s the last ruler who is usually blamed for an empire’s downfall,” says University of Toronto Assyriologist Paul-Alain Beaulieu. The enigmatic Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus seemed destined for just such a fate after the Persian armies of Cyrus the Great marched through Babylon’s gates in October 539 B.C. By deposing Nabonidus, whose reign was marked by eccentric political and religious choices, the Persians ensured that he would be the last ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539 B.C.) and the last native-born Mesopotamian king. For some 2,500 years, Mesopotamian cities, states, and empires had been ruled by their own, or by outsiders who adopted their ways. But after Nabonidus (r. 556–539 B.C.), the region was conquered by a series of foreign empires before Mesopotamia’s great ancient cities such as Ur, Uruk, and Babylon finally withered away. Many sources from antiquity cast Nabonidus as the villain who brought about the downfall of Babylon, and by extension, Mesopotamia. “He was a controversial figure,” says Beaulieu, “and perhaps a tragic one.” Today, some scholars believe that, despite being variously portrayed in ancient texts as a mad usurper and a heretic whose apostasy doomed an empire, Nabonidus may, in fact, have simply been a difficult personality with a singular political vision whose reign was cut short before he could realize his ambitions.

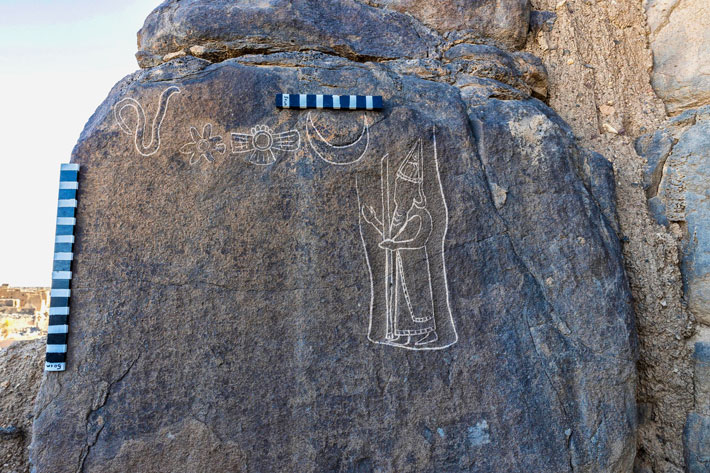

Ever since Assyriologists, who specialize in translating Mesopotamian cuneiform documents, mostly in the form of clay tablets, first began to read Neo-Babylonian records excavated in the late nineteenth century, Nabonidus has stood out as an unusual ruler. While the record is fragmentary, cuneiform tablets and inscriptions have helped scholars trace Nabonidus’ unconventional career. A palace courtier, Nabonidus came to power in his 50s or 60s by way of a coup that may have been orchestrated by his son Belshazzar, who plays a central role in the Bible’s Book of Daniel. In this biblical account, Nabonidus, who is mistakenly identified as his predecessor Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 B.C.), is described as a mad king obsessed with dreams. According to the Book of Daniel, the king leaves Babylon to live in the wilderness for seven years. This depiction overlaps somewhat with Nabonidus’ own inscriptions, in which he emphasizes that he was an especially pious man who paid heed to dreams as the divine messages of the gods. Nabonidus was also infamous in antiquity for abandoning Babylon for 10 years to live in the deserts of Saudi Arabia, where he established a kind of shadow capital at the oasis of Tayma. This was a strange and unprecedented move for a Mesopotamian ruler.

Ever since Assyriologists, who specialize in translating Mesopotamian cuneiform documents, mostly in the form of clay tablets, first began to read Neo-Babylonian records excavated in the late nineteenth century, Nabonidus has stood out as an unusual ruler. While the record is fragmentary, cuneiform tablets and inscriptions have helped scholars trace Nabonidus’ unconventional career. A palace courtier, Nabonidus came to power in his 50s or 60s by way of a coup that may have been orchestrated by his son Belshazzar, who plays a central role in the Bible’s Book of Daniel. In this biblical account, Nabonidus, who is mistakenly identified as his predecessor Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 B.C.), is described as a mad king obsessed with dreams. According to the Book of Daniel, the king leaves Babylon to live in the wilderness for seven years. This depiction overlaps somewhat with Nabonidus’ own inscriptions, in which he emphasizes that he was an especially pious man who paid heed to dreams as the divine messages of the gods. Nabonidus was also infamous in antiquity for abandoning Babylon for 10 years to live in the deserts of Saudi Arabia, where he established a kind of shadow capital at the oasis of Tayma. This was a strange and unprecedented move for a Mesopotamian ruler.

Nabonidus was also known for his near-fanatical devotion to the moon god, Sin, whom he raised to the status of the most important deity in the Babylonian pantheon. This came at the expense of Marduk, Babylon’s longtime patron god, whom earlier Neo-Babylonian kings had promoted as the empire’s chief deity. Some scholars believe that by elevating Sin, a god whose main temples lay outside the city of Babylon, Nabonidus was perhaps attempting to unite a large and diffuse empire under the worship of a god who held more appeal than Marduk to people throughout the realm. “Nabonidus was a new man, with a new vision of the Babylonian Empire,” says Beaulieu.

|

Sidebar:

|

Royal Antiquarians

|

|

Sidebar:

|

Babylon’s God King

|

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

A Monumental Imperial Biography

The Last King of Babylon

Paradise Lost

Exploring Notre Dame's Hidden Past

Letter from Doggerland

Digs & Discoveries

Poetic License

Gone Fishing

A Shining Example

Oliveopolis

Kublai Khan's Sinking Ambitions

The Treasurer's Tomb

Tudor Travelers

Who Drank From Nestor's Cup?

Reflecting the Past

Murder Will Out

Off the Grid

Around the World

Medieval war ponies, an ancient Arabian board game, the Falkland Islands wolf, and the dead of Santorini

Artifact

Connected by craft in the deep past

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Chaoui-Derieux is chief curator of heritage at the Regional Archaeology Service based in the Île-de-France, the region including and surrounding Paris. She is part of a huge team that includes at least 100 researchers from the Ministry of Culture, the French National Center for Scientific Research, and the French National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP), all dedicated to studying and restoring Notre Dame. In addition to medieval archaeologists, experts in glass, metal, wood, and stone are investigating the materials Notre Dame’s builders used and discovering how their skill would safeguard the cathedral some eight centuries after it was constructed. This work will take many years, long past the planned reopening of the restored cathedral in 2024, and thus far, has raised more questions than it has answered. But the fire has led to an archaeological project like no other.

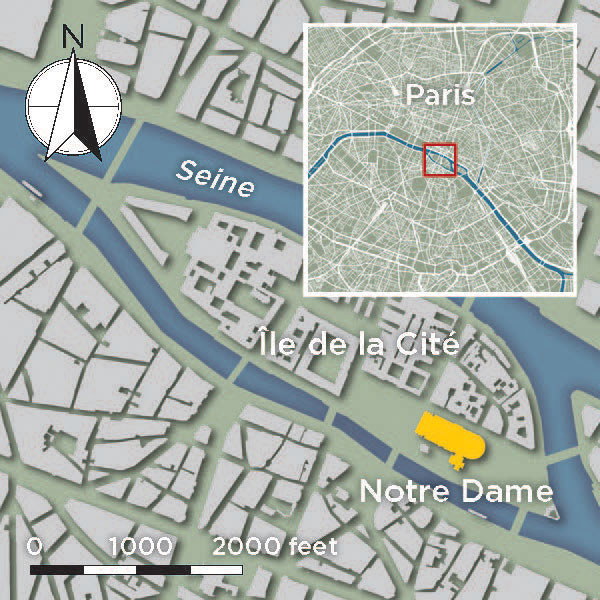

Chaoui-Derieux is chief curator of heritage at the Regional Archaeology Service based in the Île-de-France, the region including and surrounding Paris. She is part of a huge team that includes at least 100 researchers from the Ministry of Culture, the French National Center for Scientific Research, and the French National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP), all dedicated to studying and restoring Notre Dame. In addition to medieval archaeologists, experts in glass, metal, wood, and stone are investigating the materials Notre Dame’s builders used and discovering how their skill would safeguard the cathedral some eight centuries after it was constructed. This work will take many years, long past the planned reopening of the restored cathedral in 2024, and thus far, has raised more questions than it has answered. But the fire has led to an archaeological project like no other. The history of the site that would eventually be home to the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris on the Île de la Cité, or City Island, is long and varied. Paris had its origins in the Gallo-Roman town of Lutetia, on the left bank of the Seine. It took its current name from the Parisii, a Gallic tribe that had permanently settled on the island by a.d. 25, although they may have inhabited it for centuries before as it was a convenient point at which to cross the river. The site was fortified in a.d. 308 by the province’s Roman governor, and in the early sixth century A.D., the first king of the Franks, Clovis I (r. ca. A.D. 509–511), chose Paris as his capital and built a palace on the island. Later in the sixth century, Paris’ first cathedral, the cathedral of Saint Étienne, or Stephen, the first Christian martyr, was built close to the south portal of the present-day cathedral. Many other buildings and monuments were constructed over the next few centuries, most of which were torn down during eighteenth- and nineteenth-century development of the site, which included razing buildings deemed unsanitary during an 1865 cholera epidemic.

The history of the site that would eventually be home to the cathedral of Notre-Dame de Paris on the Île de la Cité, or City Island, is long and varied. Paris had its origins in the Gallo-Roman town of Lutetia, on the left bank of the Seine. It took its current name from the Parisii, a Gallic tribe that had permanently settled on the island by a.d. 25, although they may have inhabited it for centuries before as it was a convenient point at which to cross the river. The site was fortified in a.d. 308 by the province’s Roman governor, and in the early sixth century A.D., the first king of the Franks, Clovis I (r. ca. A.D. 509–511), chose Paris as his capital and built a palace on the island. Later in the sixth century, Paris’ first cathedral, the cathedral of Saint Étienne, or Stephen, the first Christian martyr, was built close to the south portal of the present-day cathedral. Many other buildings and monuments were constructed over the next few centuries, most of which were torn down during eighteenth- and nineteenth-century development of the site, which included razing buildings deemed unsanitary during an 1865 cholera epidemic. In 1163, the bishop of Paris, Maurice de Sully, began work on a new cathedral built of Lutetian limestone at the island’s eastern end on the ruins of two earlier churches, including that of Saint Étienne, and, farther down, ruins of a temple dedicated to Jupiter dating to the city’s Roman period. The current Notre Dame Cathedral measures 427 by 157 feet, soars 115 feet high, and can hold more than 6,000 people. It was mostly built by 1245, but not completed for another century.

In 1163, the bishop of Paris, Maurice de Sully, began work on a new cathedral built of Lutetian limestone at the island’s eastern end on the ruins of two earlier churches, including that of Saint Étienne, and, farther down, ruins of a temple dedicated to Jupiter dating to the city’s Roman period. The current Notre Dame Cathedral measures 427 by 157 feet, soars 115 feet high, and can hold more than 6,000 people. It was mostly built by 1245, but not completed for another century. Notre Dame is built in the Gothic style, which was widely adopted between the mid-twelfth and sixteenth centuries across Europe. The size of Romanesque-style buildings constructed prior to and in the mid-eleventh century was limited by engineering challenges that had yet to be solved. By the time Notre Dame was built, architects had begun to find solutions to these problems, and the soaring, cavernous cathedrals of medieval Europe could be constructed.

Notre Dame is built in the Gothic style, which was widely adopted between the mid-twelfth and sixteenth centuries across Europe. The size of Romanesque-style buildings constructed prior to and in the mid-eleventh century was limited by engineering challenges that had yet to be solved. By the time Notre Dame was built, architects had begun to find solutions to these problems, and the soaring, cavernous cathedrals of medieval Europe could be constructed. As Notre Dame burned through the night and the sounds of raging flames, cracking stone, and falling roof beams filled the air, many lining the Seine held their breath for the sound of shattering glass that would signal the destruction of the cathedral’s stained-glass windows. They were especially concerned about the immense circular windows—called rose windows because they resemble multi-petaled flowers—that are a defining feature of Gothic architecture. Throughout the medieval period, the designs for these windows were adapted to play with light and color, creating patterns as complex as carpets.

As Notre Dame burned through the night and the sounds of raging flames, cracking stone, and falling roof beams filled the air, many lining the Seine held their breath for the sound of shattering glass that would signal the destruction of the cathedral’s stained-glass windows. They were especially concerned about the immense circular windows—called rose windows because they resemble multi-petaled flowers—that are a defining feature of Gothic architecture. Throughout the medieval period, the designs for these windows were adapted to play with light and color, creating patterns as complex as carpets. Notre Dame’s rose windows sit over the north, south, and west portals and were completed in the early to mid-thirteenth century. They are the only windows in the cathedral to retain their original medieval glass. As daylight came up on smoldering embers, reports started to arrive from people who had trained their binoculars on the windows for hours: They were intact, thanks not least to the skills of the Parisian firefighters who had averted further disaster by aiming their hoses away from the glass as water pressure could have caused the windows to explode.

Notre Dame’s rose windows sit over the north, south, and west portals and were completed in the early to mid-thirteenth century. They are the only windows in the cathedral to retain their original medieval glass. As daylight came up on smoldering embers, reports started to arrive from people who had trained their binoculars on the windows for hours: They were intact, thanks not least to the skills of the Parisian firefighters who had averted further disaster by aiming their hoses away from the glass as water pressure could have caused the windows to explode. At the time the cathedral was built, lead was commonly used for roofing in major monuments, providing sealing for stones and the staples or metal pins inside columns, and as decoration. “Lead was a prestige material and lead workers were very important in medieval times,” says L’Héritier. “Nails, staples, and iron pins can all be sealed with mortar or by pouring in molten lead which solidifies. In Notre Dame, most examples we saw, though not all, are sealed with lead.” Hundreds of lead samples have been taken for isotope analysis and other chemical experiments. Researchers will also be able to track how lead materials were reused during past renovations and which ones might be reused as part of the current reconstruction.

At the time the cathedral was built, lead was commonly used for roofing in major monuments, providing sealing for stones and the staples or metal pins inside columns, and as decoration. “Lead was a prestige material and lead workers were very important in medieval times,” says L’Héritier. “Nails, staples, and iron pins can all be sealed with mortar or by pouring in molten lead which solidifies. In Notre Dame, most examples we saw, though not all, are sealed with lead.” Hundreds of lead samples have been taken for isotope analysis and other chemical experiments. Researchers will also be able to track how lead materials were reused during past renovations and which ones might be reused as part of the current reconstruction. One major discovery after the fire is that staples were used throughout the entire construction process of Notre Dame. These staples are currently being dated and analyzed to better understand where they came from, how they were made, and how they were used in the building. This will give scholars more information about the city’s trading system during the medieval period. “Unlike other medieval buildings studied so far, many different iron sources seem to have been called for at Notre Dame,” says L’Héritier. “These artifacts are keys to better understanding the Parisian iron market in medieval times.”

One major discovery after the fire is that staples were used throughout the entire construction process of Notre Dame. These staples are currently being dated and analyzed to better understand where they came from, how they were made, and how they were used in the building. This will give scholars more information about the city’s trading system during the medieval period. “Unlike other medieval buildings studied so far, many different iron sources seem to have been called for at Notre Dame,” says L’Héritier. “These artifacts are keys to better understanding the Parisian iron market in medieval times.” Gallet’s group has made additional significant discoveries since the fire. Part of their work is to identify notations left by the stonecutters, either to mark the stones they had cut themselves so they could be paid for their work or to indicate the direction in which a stone was to be laid. Analysis of the voussoirs—wedge-shaped stones used to form arches—recovered from the floor of the nave after the double arch above collapsed has shown that stonemasons carved crosses on one side. This detail has allowed researchers to redate the construction of the vaults. “These crosses were not used in the Île-de-France until after the 1220s,” says Gallet. “This led to a rethinking of the chronology of the site.”

Gallet’s group has made additional significant discoveries since the fire. Part of their work is to identify notations left by the stonecutters, either to mark the stones they had cut themselves so they could be paid for their work or to indicate the direction in which a stone was to be laid. Analysis of the voussoirs—wedge-shaped stones used to form arches—recovered from the floor of the nave after the double arch above collapsed has shown that stonemasons carved crosses on one side. This detail has allowed researchers to redate the construction of the vaults. “These crosses were not used in the Île-de-France until after the 1220s,” says Gallet. “This led to a rethinking of the chronology of the site.”

There are also more modern marks. Close examination of the keystone, or central voussoir, in the south arm of the transept revealed the engraved date 1728. The inscription is not visible from below, and no one had ever documented it. “Until now, the scientific literature made no mention of these marks. It’s therefore a novelty, and one which places Notre Dame in a very different perspective,” says Gallet. “This is an unexpected date because art historians have always believed that this keystone dated either from the Gothic period or from the nineteenth-century restorations. We’re still thinking about the best interpretation.”

There are also more modern marks. Close examination of the keystone, or central voussoir, in the south arm of the transept revealed the engraved date 1728. The inscription is not visible from below, and no one had ever documented it. “Until now, the scientific literature made no mention of these marks. It’s therefore a novelty, and one which places Notre Dame in a very different perspective,” says Gallet. “This is an unexpected date because art historians have always believed that this keystone dated either from the Gothic period or from the nineteenth-century restorations. We’re still thinking about the best interpretation.” Perhaps the most extraordinary thing that Gallet’s team has learned thus far is what role medieval craftspeople played in saving Notre Dame during the fire. “What protected the cathedral were its vaults,” Gallet says. “Most of them resisted the fire, which was remarkable, especially as examination of the vaults since then confirms that the ribs are very thin, only around six inches thick, and had to support a 42-foot-wide vault that was 100 feet aboveground.” The only major vault that collapsed did so because it was unable to withstand the sudden weight of the crumbling upper section of the spire. “The vaults played the role of firewall,” says Gallet. “If there had been no stone vaults, the flaming beams of the roof would have fallen to the ground and shattered the stones of the supporting piers. And then the whole cathedral would have collapsed.”

Perhaps the most extraordinary thing that Gallet’s team has learned thus far is what role medieval craftspeople played in saving Notre Dame during the fire. “What protected the cathedral were its vaults,” Gallet says. “Most of them resisted the fire, which was remarkable, especially as examination of the vaults since then confirms that the ribs are very thin, only around six inches thick, and had to support a 42-foot-wide vault that was 100 feet aboveground.” The only major vault that collapsed did so because it was unable to withstand the sudden weight of the crumbling upper section of the spire. “The vaults played the role of firewall,” says Gallet. “If there had been no stone vaults, the flaming beams of the roof would have fallen to the ground and shattered the stones of the supporting piers. And then the whole cathedral would have collapsed.” Thus, when Lieutenant-Colonel John Winslow, a British military commander from Massachusetts, arrived at Grand Pré with a detachment of 300 troops on August 19, 1755, many local Acadians assumed this was just the latest attempt to secure their allegiance. When Winslow and his men set up camp in and around the parish church, Saint-Charles-des-Mines, and surrounded it with a defensive palisade, few Acadians panicked. And, on Friday, September 5, when Winslow summoned all men and boys older than 10 living in the village and the surrounding district to meet with him in the church, 418 residents showed up. They were greatly shocked, then, to hear the commander read a proclamation stating that they would have to forfeit their land, livestock, and most other possessions, and that they and their families would be forced to leave their land. Similar messages were delivered to communities elsewhere in Nova Scotia, and over the next few months, more than 6,000 Acadians living there were shipped to destinations throughout the Americas and Europe in overcrowded, inhumane conditions. The remainder fled to the peninsula’s interior to live with the Mi’kmaq, to French-controlled Île Saint-Jean (modern-day Prince Edward Island), or to New Brunswick, which was contested territory at the time. Around 1,000 Acadians perished on the deportation journeys due to shipwreck or disease, and many others were separated from their families. Several thousand more Acadians were expelled from the region over the next few years. (See “

Thus, when Lieutenant-Colonel John Winslow, a British military commander from Massachusetts, arrived at Grand Pré with a detachment of 300 troops on August 19, 1755, many local Acadians assumed this was just the latest attempt to secure their allegiance. When Winslow and his men set up camp in and around the parish church, Saint-Charles-des-Mines, and surrounded it with a defensive palisade, few Acadians panicked. And, on Friday, September 5, when Winslow summoned all men and boys older than 10 living in the village and the surrounding district to meet with him in the church, 418 residents showed up. They were greatly shocked, then, to hear the commander read a proclamation stating that they would have to forfeit their land, livestock, and most other possessions, and that they and their families would be forced to leave their land. Similar messages were delivered to communities elsewhere in Nova Scotia, and over the next few months, more than 6,000 Acadians living there were shipped to destinations throughout the Americas and Europe in overcrowded, inhumane conditions. The remainder fled to the peninsula’s interior to live with the Mi’kmaq, to French-controlled Île Saint-Jean (modern-day Prince Edward Island), or to New Brunswick, which was contested territory at the time. Around 1,000 Acadians perished on the deportation journeys due to shipwreck or disease, and many others were separated from their families. Several thousand more Acadians were expelled from the region over the next few years. (See “ A sense of tragic loss pervaded Acadians’ memories in the decades after 1755, which is reflected in their term for the removal period, le grand dérangement, or “the great upheaval.” Most wounding was the widespread separation of family members. This sentiment was crystallized by Massachusetts poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his wildly popular 1847 epic Evangeline. In it, he portrays the Acadians and their expulsion in highly romantic terms, describing Grand Pré as “the forest primeval,” evoking the “wail of sorrow and anger” that erupts from the men and boys in the parish church when they hear Winslow’s proclamation, and depicting the deportees as “scattered…like flakes of snow” in the driving wind. The poem focuses on a fictional young couple from Grand Pré, Evangeline and Gabriel, who are separated on their wedding day. Evangeline spends the rest of her life trying to track down her beloved only to find him in an almshouse in Philadelphia on the verge of death. They embrace, lamenting the life together that was stolen from them, and he dies in her arms. She follows soon after, and they are buried side by side. “Once Longfellow’s poem became famous, people began visiting sleepy little Grand Pré,” says Fowler. “It was never really well known before, but came to be seen as a kind of holy place in Acadian history.”

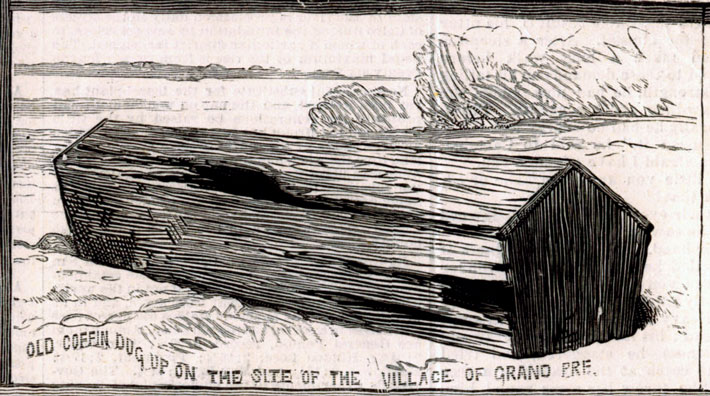

A sense of tragic loss pervaded Acadians’ memories in the decades after 1755, which is reflected in their term for the removal period, le grand dérangement, or “the great upheaval.” Most wounding was the widespread separation of family members. This sentiment was crystallized by Massachusetts poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in his wildly popular 1847 epic Evangeline. In it, he portrays the Acadians and their expulsion in highly romantic terms, describing Grand Pré as “the forest primeval,” evoking the “wail of sorrow and anger” that erupts from the men and boys in the parish church when they hear Winslow’s proclamation, and depicting the deportees as “scattered…like flakes of snow” in the driving wind. The poem focuses on a fictional young couple from Grand Pré, Evangeline and Gabriel, who are separated on their wedding day. Evangeline spends the rest of her life trying to track down her beloved only to find him in an almshouse in Philadelphia on the verge of death. They embrace, lamenting the life together that was stolen from them, and he dies in her arms. She follows soon after, and they are buried side by side. “Once Longfellow’s poem became famous, people began visiting sleepy little Grand Pré,” says Fowler. “It was never really well known before, but came to be seen as a kind of holy place in Acadian history.” Among those who made the pilgrimage to Grand Pré after Longfellow published Evangeline were amateur antiquarians, who dug up several wooden coffins from the Acadian cemetery near the parish church. One coffin was put on display at a local hotel and another was left at the town’s railroad station, where visitors took it away in parts as souvenirs. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Acadian descendant John Frederic Herbin purchased the land where the cemetery was located and marked it with a stone cross. Then, in the 1920s, a bronze statue of Evangeline was erected and Acadians built a memorial church on the purported site of the 1755 roundup. In 1982, Parks Canada established the Grand-Pré National Historic Site, encompassing the area surrounding the memorial church and Herbin’s Cross. That same year, Parks Canada archaeologists found four grave shafts just north of the cross, confirming that it marks the site of the Acadian cemetery.

Among those who made the pilgrimage to Grand Pré after Longfellow published Evangeline were amateur antiquarians, who dug up several wooden coffins from the Acadian cemetery near the parish church. One coffin was put on display at a local hotel and another was left at the town’s railroad station, where visitors took it away in parts as souvenirs. In the first decade of the twentieth century, Acadian descendant John Frederic Herbin purchased the land where the cemetery was located and marked it with a stone cross. Then, in the 1920s, a bronze statue of Evangeline was erected and Acadians built a memorial church on the purported site of the 1755 roundup. In 1982, Parks Canada established the Grand-Pré National Historic Site, encompassing the area surrounding the memorial church and Herbin’s Cross. That same year, Parks Canada archaeologists found four grave shafts just north of the cross, confirming that it marks the site of the Acadian cemetery. In May 2006, Fowler was called to the Grand Pré marsh, where a machinery operator had unearthed a wooden sluice. This turned out to be an aboiteau, the linchpin of Acadian dikeland agriculture. Essentially a hollowed-out white pine log, it was equipped with a valve that allowed water to drain out of the marsh but blocked seawater from entering as the tide rose. Sod, spruce brush, and wooden stakes were found packed around the aboiteau. The sod was densely matted with marsh grass whose roots grew together to help hold the dikes in place against the onslaught of the tides, while the stakes strengthened the structure, akin to how rebar reinforces concrete. “The preservation of the aboiteau was just stunning,” says Fowler. “You could still see the ax marks, and the spruce boughs and marsh grass were still green. It was a really impressive sight.” The aboiteau was dated to 1691 using dendrochronology, meaning it was put in place within the first decade after Grand Pré was settled. The sluice was found near the middle of the marsh, which is known to be where the Acadians began their land reclamation project. They then worked their way out, diking off the land section by section. By 1755, they had built nearly 19 miles of dike walls to reclaim nearly four square miles of tidal marsh and turned it into a network of highly productive fields.

In May 2006, Fowler was called to the Grand Pré marsh, where a machinery operator had unearthed a wooden sluice. This turned out to be an aboiteau, the linchpin of Acadian dikeland agriculture. Essentially a hollowed-out white pine log, it was equipped with a valve that allowed water to drain out of the marsh but blocked seawater from entering as the tide rose. Sod, spruce brush, and wooden stakes were found packed around the aboiteau. The sod was densely matted with marsh grass whose roots grew together to help hold the dikes in place against the onslaught of the tides, while the stakes strengthened the structure, akin to how rebar reinforces concrete. “The preservation of the aboiteau was just stunning,” says Fowler. “You could still see the ax marks, and the spruce boughs and marsh grass were still green. It was a really impressive sight.” The aboiteau was dated to 1691 using dendrochronology, meaning it was put in place within the first decade after Grand Pré was settled. The sluice was found near the middle of the marsh, which is known to be where the Acadians began their land reclamation project. They then worked their way out, diking off the land section by section. By 1755, they had built nearly 19 miles of dike walls to reclaim nearly four square miles of tidal marsh and turned it into a network of highly productive fields. When Parks Canada archaeologists identified grave shafts near Herbin’s Cross in 1982, they unearthed nails and soil stains from the coffins, but the coffins and human skeletons had been eaten away by the site’s acidic soil. Building on this discovery, Fowler has used ground-penetrating radar to map the rest of the Acadian parish cemetery and located 289 graves. On two sides of the cemetery, he has identified thin lines that he interprets as fence lines demarcating its eastern and western edges. In one of these lines, Fowler unearthed carbonized seeds, including oats and peas, traditional staples of the French diet during the period, which he describes as “the fingerprint of the Acadians,” as well as blueberries, which grow wild in the area. “That shows a culture adapting,” Fowler says. “I can imagine the conversations between the European newcomers and the Indigenous inhabitants of the land: ‘Can I eat this, or will it kill me?’”

When Parks Canada archaeologists identified grave shafts near Herbin’s Cross in 1982, they unearthed nails and soil stains from the coffins, but the coffins and human skeletons had been eaten away by the site’s acidic soil. Building on this discovery, Fowler has used ground-penetrating radar to map the rest of the Acadian parish cemetery and located 289 graves. On two sides of the cemetery, he has identified thin lines that he interprets as fence lines demarcating its eastern and western edges. In one of these lines, Fowler unearthed carbonized seeds, including oats and peas, traditional staples of the French diet during the period, which he describes as “the fingerprint of the Acadians,” as well as blueberries, which grow wild in the area. “That shows a culture adapting,” Fowler says. “I can imagine the conversations between the European newcomers and the Indigenous inhabitants of the land: ‘Can I eat this, or will it kill me?’” Still, the site of the parish church where Winslow read the deportation order remained elusive. “Our question was, did the people who built the memorial church to mark the spot get it right?” says Fowler. “There had been no professional archaeology done to ascertain whether that was true or not. It was all based on folklore and decisions that were made 100 years ago.” In surveys of Winslow’s camp, Fowler and his team had uncovered the cellars of two Acadian houses, but no foundations large enough to have been the parish church. Then, using magnetic sensing equipment, he detected a burned patch of ground measuring roughly 100 feet by 30 feet. When raised to a high temperature, iron, which is abundant in soil, is magnetized. Fowler’s team carried out excavations of this footprint and determined that a timber building constructed using wattle and daub, which is typical of French colonial architecture, had once stood on the site. Artifacts unearthed below the burn layer date to the French colonial period, whereas those above it date to the late eighteenth century and into modern times, further evidence that the structure was built by the Acadians and then burned at the time of the expulsion or shortly thereafter.

Still, the site of the parish church where Winslow read the deportation order remained elusive. “Our question was, did the people who built the memorial church to mark the spot get it right?” says Fowler. “There had been no professional archaeology done to ascertain whether that was true or not. It was all based on folklore and decisions that were made 100 years ago.” In surveys of Winslow’s camp, Fowler and his team had uncovered the cellars of two Acadian houses, but no foundations large enough to have been the parish church. Then, using magnetic sensing equipment, he detected a burned patch of ground measuring roughly 100 feet by 30 feet. When raised to a high temperature, iron, which is abundant in soil, is magnetized. Fowler’s team carried out excavations of this footprint and determined that a timber building constructed using wattle and daub, which is typical of French colonial architecture, had once stood on the site. Artifacts unearthed below the burn layer date to the French colonial period, whereas those above it date to the late eighteenth century and into modern times, further evidence that the structure was built by the Acadians and then burned at the time of the expulsion or shortly thereafter. Scholars have always believed that the six slabs of the frieze, which are above the two small arches at both the monument’s front and back, as well as on each of its two sides, are also Constantinian-era components. But University of Pennsylvania archaeologist C. Brian Rose has a different idea. “I always wanted to look into the problem of why the emperor’s heads were clearly re-carved and why the legs and feet of so many people depicted on the frieze are missing,” he says. “The more I read, the more interested I became and the more I thought these reliefs must be reused elements from some other monument.” This would, says Rose, mean rethinking more than a century of scholarship and creating a new biography of the arch.

Scholars have always believed that the six slabs of the frieze, which are above the two small arches at both the monument’s front and back, as well as on each of its two sides, are also Constantinian-era components. But University of Pennsylvania archaeologist C. Brian Rose has a different idea. “I always wanted to look into the problem of why the emperor’s heads were clearly re-carved and why the legs and feet of so many people depicted on the frieze are missing,” he says. “The more I read, the more interested I became and the more I thought these reliefs must be reused elements from some other monument.” This would, says Rose, mean rethinking more than a century of scholarship and creating a new biography of the arch. In reconsidering the monument’s creation, scholars are also investigating how ancient viewers would have experienced it, and indeed this entire quarter of the city, which was packed with monuments dating from all periods of Rome’s past. By Constantine’s time, Rome had a 1,000-year history, and very little space remained in the city center for his architects to honor him. How they solved this problem and created a uniquely Constantinian space is a testament not only to their skill, but also to their understanding of the complex realities of the late Roman Empire, where awareness of the past was one way to ensure success in the future.

In reconsidering the monument’s creation, scholars are also investigating how ancient viewers would have experienced it, and indeed this entire quarter of the city, which was packed with monuments dating from all periods of Rome’s past. By Constantine’s time, Rome had a 1,000-year history, and very little space remained in the city center for his architects to honor him. How they solved this problem and created a uniquely Constantinian space is a testament not only to their skill, but also to their understanding of the complex realities of the late Roman Empire, where awareness of the past was one way to ensure success in the future. The Arch of Constantine’s frieze is composed of six carved marble slabs depicting different scenes, five of which include the emperor: his adventus, or formal entry into Rome; an oratio in which he delivers a speech in the forum; a liberalitas in which he gives money to his subjects; a battle by a river; and troops besieging a walled city. The sixth shows a marching army.

The Arch of Constantine’s frieze is composed of six carved marble slabs depicting different scenes, five of which include the emperor: his adventus, or formal entry into Rome; an oratio in which he delivers a speech in the forum; a liberalitas in which he gives money to his subjects; a battle by a river; and troops besieging a walled city. The sixth shows a marching army. Constantine decided not to clear out room in this highly symbolic area of the city to create his own forum, as many of his predecessors had. “He was the first emperor to see the center of Rome as a historical landscape and to think of it as an inherited architectural heritage to preserve and, when appropriate, to make his own,” Marlowe says. “Constantine was picking pieces of Rome’s long, imperial history and repackaging it—and himself—in a self-conscious way.” For example, the massive basilica built by the emperor’s rival Maxentius not far from the Colosseum was rededicated to Constantine, its entrance and orientation shifted, and a huge, seated statue of the new emperor placed in the structure to “offer the spectator a totally new, Constantinian experience of the building,” says Marlowe. This stands in stark contrast, for example, to the treatment given to the Domus Aurea, or Golden House, the gargantuan private palace built by the emperor Nero (r. A.D. 54–68) on the Palatine and Esquiline Hills overlooking this part of the city. After Nero’s suicide, his successors largely covered over the Domus Aurea and turned the new space into a public park. Other parts of the palace were torn down to make room for the Colosseum.

Constantine decided not to clear out room in this highly symbolic area of the city to create his own forum, as many of his predecessors had. “He was the first emperor to see the center of Rome as a historical landscape and to think of it as an inherited architectural heritage to preserve and, when appropriate, to make his own,” Marlowe says. “Constantine was picking pieces of Rome’s long, imperial history and repackaging it—and himself—in a self-conscious way.” For example, the massive basilica built by the emperor’s rival Maxentius not far from the Colosseum was rededicated to Constantine, its entrance and orientation shifted, and a huge, seated statue of the new emperor placed in the structure to “offer the spectator a totally new, Constantinian experience of the building,” says Marlowe. This stands in stark contrast, for example, to the treatment given to the Domus Aurea, or Golden House, the gargantuan private palace built by the emperor Nero (r. A.D. 54–68) on the Palatine and Esquiline Hills overlooking this part of the city. After Nero’s suicide, his successors largely covered over the Domus Aurea and turned the new space into a public park. Other parts of the palace were torn down to make room for the Colosseum. Marlowe believes Constantine also fashioned another very deliberate link to Rome’s past when selecting the location of his arch. To accommodate the arch in this densely packed, monument-filled area, Constantine’s architects made the unusual decision to erect it in an open space next to the Colosseum, at an odd angle to the Triumphal Way, not straddling it, as many previous arches had. “We think of the Roman notions of space as right angles and grids and symmetry,” Marlowe says. “The idea that they would build this monument even a little bit off-center radically defies our ideas of what Roman architecture and city planning were about.” Because the arch was not centered on the road, Marlowe explains, the emperor was able to mark the location with a Constantinian stamp.

Marlowe believes Constantine also fashioned another very deliberate link to Rome’s past when selecting the location of his arch. To accommodate the arch in this densely packed, monument-filled area, Constantine’s architects made the unusual decision to erect it in an open space next to the Colosseum, at an odd angle to the Triumphal Way, not straddling it, as many previous arches had. “We think of the Roman notions of space as right angles and grids and symmetry,” Marlowe says. “The idea that they would build this monument even a little bit off-center radically defies our ideas of what Roman architecture and city planning were about.” Because the arch was not centered on the road, Marlowe explains, the emperor was able to mark the location with a Constantinian stamp. Nabonidus’ efforts to hold together his realm may have ultimately gone unrealized, but by exploring his reign, scholars can learn much about the final days of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Nabonidus left behind some 3,000 cuneiform inscriptions, far more than any other Neo-Babylonian king. New readings of some of these tablets, findings from excavations at Tayma, and the recent discovery of additional inscriptions dating to Nabonidus’ reign are all giving scholars a chance to tease out the ambiguities that lay at the heart of the reign of Babylon’s last king.

Nabonidus’ efforts to hold together his realm may have ultimately gone unrealized, but by exploring his reign, scholars can learn much about the final days of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Nabonidus left behind some 3,000 cuneiform inscriptions, far more than any other Neo-Babylonian king. New readings of some of these tablets, findings from excavations at Tayma, and the recent discovery of additional inscriptions dating to Nabonidus’ reign are all giving scholars a chance to tease out the ambiguities that lay at the heart of the reign of Babylon’s last king.  Babylon’s New Year festival, held during the spring, was Marduk’s special holiday and the city’s most important rite. The god’s statue was carried from its home at the Esagila Temple to a series of other sanctuaries during 14 days of lavish rituals celebrated throughout the city. During this festival, the king’s sacred right to rule was renewed for another year.

Babylon’s New Year festival, held during the spring, was Marduk’s special holiday and the city’s most important rite. The god’s statue was carried from its home at the Esagila Temple to a series of other sanctuaries during 14 days of lavish rituals celebrated throughout the city. During this festival, the king’s sacred right to rule was renewed for another year.  After his lengthy reign, Nebuchadnezzar II was succeeded by his son-in-law Neriglissar (r. 560–556 B.C.), who sat on the throne for just four years. He in turn was eventually succeeded by his son Labashi-Marduk, who reigned for a mere two weeks before a coup deposed him and placed an already elderly Nabonidus on the throne.

After his lengthy reign, Nebuchadnezzar II was succeeded by his son-in-law Neriglissar (r. 560–556 B.C.), who sat on the throne for just four years. He in turn was eventually succeeded by his son Labashi-Marduk, who reigned for a mere two weeks before a coup deposed him and placed an already elderly Nabonidus on the throne. Sandowicz has found that many men in these records held high titles and were the kind of palace officials one would expect to find in close proximity to the king. A smaller number of men without titles seem to have been Nabonidus’ more intimate associates. Some of them had held positions of power under Nebuchadnezzar II and Neriglissar. They seem to have retained the king’s special favor, suggesting that these companions of Nabonidus could have been critical allies in the coup that installed him as king. Quite a few members of this royal retinue were Aramaeans, an ethnic group whose tribes lived across the Neo-Babylonian Empire. A native of the northern city of Harran, where many Aramaeans lived, Nabonidus may well have been Aramaean himself. At this time, the Aramaeans’ Semitic language, Aramaic, was rapidly displacing Akkadian as the empire’s leading language. “Aramaeans are hard to identify in Babylonian records,” says Sandowicz. “They often managed their affairs in the framework of their own tribal institutions. So the fact that they appear here as associates of the king is significant.” If Nabonidus maintained close links with Aramaeans, that could indicate he might have been interested in keeping a power base outside the official Babylonian system.

Sandowicz has found that many men in these records held high titles and were the kind of palace officials one would expect to find in close proximity to the king. A smaller number of men without titles seem to have been Nabonidus’ more intimate associates. Some of them had held positions of power under Nebuchadnezzar II and Neriglissar. They seem to have retained the king’s special favor, suggesting that these companions of Nabonidus could have been critical allies in the coup that installed him as king. Quite a few members of this royal retinue were Aramaeans, an ethnic group whose tribes lived across the Neo-Babylonian Empire. A native of the northern city of Harran, where many Aramaeans lived, Nabonidus may well have been Aramaean himself. At this time, the Aramaeans’ Semitic language, Aramaic, was rapidly displacing Akkadian as the empire’s leading language. “Aramaeans are hard to identify in Babylonian records,” says Sandowicz. “They often managed their affairs in the framework of their own tribal institutions. So the fact that they appear here as associates of the king is significant.” If Nabonidus maintained close links with Aramaeans, that could indicate he might have been interested in keeping a power base outside the official Babylonian system.  During this first phase of his rule, Nabonidus claims to have rebuilt the walls of Babylon, a boast made by nearly every Babylonian king, and to have ordered the rebuilding of temples throughout Mesopotamia. As part of these temple renovations, he was particularly interested in recovering ancient religious cuneiform dedications and statues, and ordered special excavations to hunt for them. He was already making the worship of Sin the centerpiece of his rule. In the second year of his reign, he rededicated the temple of Sin in Ur during a lunar eclipse. He also established his daughter as the main priestess there, evidence of how much he valued his personal connection to the god. Perhaps he wanted to be sure he had a close relative keeping an eye on the priests of the god to whom he was so devoted.

During this first phase of his rule, Nabonidus claims to have rebuilt the walls of Babylon, a boast made by nearly every Babylonian king, and to have ordered the rebuilding of temples throughout Mesopotamia. As part of these temple renovations, he was particularly interested in recovering ancient religious cuneiform dedications and statues, and ordered special excavations to hunt for them. He was already making the worship of Sin the centerpiece of his rule. In the second year of his reign, he rededicated the temple of Sin in Ur during a lunar eclipse. He also established his daughter as the main priestess there, evidence of how much he valued his personal connection to the god. Perhaps he wanted to be sure he had a close relative keeping an eye on the priests of the god to whom he was so devoted.  After three years of rule, and without any clear explanation, Nabonidus abandoned Babylon. Leaving his son Belshazzar as regent, he disappeared for a decade to campaign in the wastes of northern Arabia. “We don’t know why he did this, at his age,” says Hanspeter Schaudig, a Heidelberg University Assyriologist. “It would have made much more sense for his son to lead the army and for him to stay at the capital to maintain power and oversee religious rites there.” It is possible that clashes with the priests of Marduk, and perhaps even with his son, impelled Nabonidus to quit Babylon. In his absence, the city’s New Year ceremony and the renewal of the king’s authority went uncelebrated for 10 years, and Marduk languished in the Esagila Temple. Later accounts may exaggerate the extent to which this troubled the Babylonians, but it probably was a source of great anxiety for many in the city.

After three years of rule, and without any clear explanation, Nabonidus abandoned Babylon. Leaving his son Belshazzar as regent, he disappeared for a decade to campaign in the wastes of northern Arabia. “We don’t know why he did this, at his age,” says Hanspeter Schaudig, a Heidelberg University Assyriologist. “It would have made much more sense for his son to lead the army and for him to stay at the capital to maintain power and oversee religious rites there.” It is possible that clashes with the priests of Marduk, and perhaps even with his son, impelled Nabonidus to quit Babylon. In his absence, the city’s New Year ceremony and the renewal of the king’s authority went uncelebrated for 10 years, and Marduk languished in the Esagila Temple. Later accounts may exaggerate the extent to which this troubled the Babylonians, but it probably was a source of great anxiety for many in the city.  Some 350 miles to southwest of Sela, a Saudi-German team now led by the German Archaeological Institute’s Arnulf Hausleiter has been excavating at the oasis of Tayma since 2005. Before they began, Nabonidus’ presence at the oasis was only known from the literary record. In surveys and excavations, however, they have found structures and inscriptions dating to the period of Nabonidus’ residence there, and a number of artifacts bearing the king’s name. The formal cuneiform inscriptions discovered by the team, including a weathered stela excavated from the site, are largely fragmentary, but are similar to the monuments Nabonidus erected at Babylon. This came as a surprise to Schaudig, who translated the Neo-Babylonian texts found at Tayma. “I thought out in the desert he would have commissioned inscriptions that would have expressed more independent thinking,” says Schaudig. “But they repeat the form of ones from Babylonia.”

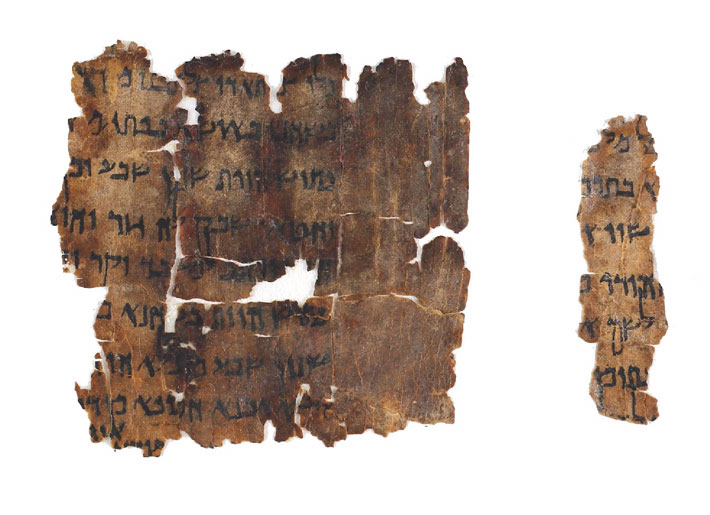

Some 350 miles to southwest of Sela, a Saudi-German team now led by the German Archaeological Institute’s Arnulf Hausleiter has been excavating at the oasis of Tayma since 2005. Before they began, Nabonidus’ presence at the oasis was only known from the literary record. In surveys and excavations, however, they have found structures and inscriptions dating to the period of Nabonidus’ residence there, and a number of artifacts bearing the king’s name. The formal cuneiform inscriptions discovered by the team, including a weathered stela excavated from the site, are largely fragmentary, but are similar to the monuments Nabonidus erected at Babylon. This came as a surprise to Schaudig, who translated the Neo-Babylonian texts found at Tayma. “I thought out in the desert he would have commissioned inscriptions that would have expressed more independent thinking,” says Schaudig. “But they repeat the form of ones from Babylonia.”  One of the simplest explanations for Nabonidus’ 10-year absence from Babylon is that he was endeavoring to extend the might of the empire to the south and trying to gain control of the valuable trade routes of western Arabia. Other explanations offered by ancient sources—apart from the idea that the king was simply mad—include the suggestion that Nabonidus suffered from some ailment he hoped time in the desert might cure. Parchment fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls discovered in the Qumran caves of the West Bank offer a version of this story. These fragments preserve a literary work known as “The Prayer of Nabonidus,” which may have originally been composed by Judeans living in Babylon. Its author or authors suggest the king suffered from a severe skin condition and fled Babylon, perhaps to avoid polluting its sacred temples with his unclean body. Once in the desert, he prayed to the god of the Judeans for relief. The source of this story could have been an urban legend that arose in Babylon during Nabonidus’ absence and may have also helped inspire the account of the mad king in the Book of Daniel. Perhaps it was whispered that the king fled to the desert to pray to Sin, the moon god, for a cure to a leprosy-like malady. Other Babylonian works suggest the god, by virtue of the moon’s pitted surface, was able to cure diseases of the skin. Whether or not he had an illness that was relieved by his stay in Arabia, by 543 B.C. Nabonidus had returned to Babylon with his devotion to Sin undiminished.