The fall of an empire in antiquity was usually the result of complex, interconnected factors that lay beyond the scope of any one person’s control. Nonetheless, traumatized contemporaries and later historians alike have often laid the fault at the feet of a single individual. “It’s the last ruler who is usually blamed for an empire’s downfall,” says University of Toronto Assyriologist Paul-Alain Beaulieu. The enigmatic Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus seemed destined for just such a fate after the Persian armies of Cyrus the Great marched through Babylon’s gates in October 539 B.C. By deposing Nabonidus, whose reign was marked by eccentric political and religious choices, the Persians ensured that he would be the last ruler of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (626–539 B.C.) and the last native-born Mesopotamian king. For some 2,500 years, Mesopotamian cities, states, and empires had been ruled by their own, or by outsiders who adopted their ways. But after Nabonidus (r. 556–539 B.C.), the region was conquered by a series of foreign empires before Mesopotamia’s great ancient cities such as Ur, Uruk, and Babylon finally withered away. Many sources from antiquity cast Nabonidus as the villain who brought about the downfall of Babylon, and by extension, Mesopotamia. “He was a controversial figure,” says Beaulieu, “and perhaps a tragic one.” Today, some scholars believe that, despite being variously portrayed in ancient texts as a mad usurper and a heretic whose apostasy doomed an empire, Nabonidus may, in fact, have simply been a difficult personality with a singular political vision whose reign was cut short before he could realize his ambitions.

Ever since Assyriologists, who specialize in translating Mesopotamian cuneiform documents, mostly in the form of clay tablets, first began to read Neo-Babylonian records excavated in the late nineteenth century, Nabonidus has stood out as an unusual ruler. While the record is fragmentary, cuneiform tablets and inscriptions have helped scholars trace Nabonidus’ unconventional career. A palace courtier, Nabonidus came to power in his 50s or 60s by way of a coup that may have been orchestrated by his son Belshazzar, who plays a central role in the Bible’s Book of Daniel. In this biblical account, Nabonidus, who is mistakenly identified as his predecessor Nebuchadnezzar II (r. 605–562 B.C.), is described as a mad king obsessed with dreams. According to the Book of Daniel, the king leaves Babylon to live in the wilderness for seven years. This depiction overlaps somewhat with Nabonidus’ own inscriptions, in which he emphasizes that he was an especially pious man who paid heed to dreams as the divine messages of the gods. Nabonidus was also infamous in antiquity for abandoning Babylon for 10 years to live in the deserts of Saudi Arabia, where he established a kind of shadow capital at the oasis of Tayma. This was a strange and unprecedented move for a Mesopotamian ruler.

Nabonidus was also known for his near-fanatical devotion to the moon god, Sin, whom he raised to the status of the most important deity in the Babylonian pantheon. This came at the expense of Marduk, Babylon’s longtime patron god, whom earlier Neo-Babylonian kings had promoted as the empire’s chief deity. Some scholars believe that by elevating Sin, a god whose main temples lay outside the city of Babylon, Nabonidus was perhaps attempting to unite a large and diffuse empire under the worship of a god who held more appeal than Marduk to people throughout the realm. “Nabonidus was a new man, with a new vision of the Babylonian Empire,” says Beaulieu.

Nabonidus’ efforts to hold together his realm may have ultimately gone unrealized, but by exploring his reign, scholars can learn much about the final days of the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Nabonidus left behind some 3,000 cuneiform inscriptions, far more than any other Neo-Babylonian king. New readings of some of these tablets, findings from excavations at Tayma, and the recent discovery of additional inscriptions dating to Nabonidus’ reign are all giving scholars a chance to tease out the ambiguities that lay at the heart of the reign of Babylon’s last king.

For most of the third millennium B.C., Babylon was just one of many Sumerian city-states that flourished in southern Mesopotamia. Older cities such as Ur, whose patron deity was the moon god, Nanna—later known as Sin—were much more powerful. Around 2000 B.C., Babylon began to acquire a reputation as a religious center and place of scholarship. By then its residents spoke Akkadian, a Semitic language that had replaced Sumerian as the lingua franca of Mesopotamia. During this period, after the rise of what scholars today call the Old Babylonian Dynasty and the ascension of rulers such as Hammurabi (r. ca. 1810–1750 B.C.), Babylon became the region’s most influential city. Previously a minor storm god, Marduk became its patron and was gradually elevated to his position as one of the most powerful deities in the Mesopotamian pantheon.

Babylon’s New Year festival, held during the spring, was Marduk’s special holiday and the city’s most important rite. The god’s statue was carried from its home at the Esagila Temple to a series of other sanctuaries during 14 days of lavish rituals celebrated throughout the city. During this festival, the king’s sacred right to rule was renewed for another year.

Throughout the second and early first millennia B.C., Babylon’s status as Mesopotamia’s leading city waxed and waned. Although it was sometimes seized by foreigners, these outsiders always eventually adopted Babylonian culture, becoming indistinguishable from the city’s Akkadian-speaking citizens. After living under the kings of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 B.C.) for several centuries, Babylonians, led by a local chieftain named Nabopolassar (r. 626–605 B.C.), revolted and, after a protracted civil war, seized power, establishing the Neo-Babylonian Empire. This ushered in a period that saw Babylon become an imperial capital as its armies conquered much of the territory previously ruled by Neo-Assyrian kings.

Nabopolassar was succeeded by his son Nebuchadnezzar II, who was known for his military conquests, including the capture of Jerusalem, and his building projects, which included the construction of the city’s famed Ishtar Gate. The gate was decorated with colorful molded and glazed bricks, some of which depict a mušhuššu, the mythological dragon that was Marduk’s totemic animal. In the last decade of the seventh century B.C., Babylonian forces conquered the final remnants of the Neo-Assyrian Empire to the north, including Harran, the home city of Nabonidus’ family. At that time, his mother, Adad-guppi, a priestess of Sin, was brought to Babylon, perhaps with her son, whom she may have established at court in a position of influence.

Some tablets dating to the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II mention an official named Nabonidus, which might refer to the future king. Some of these texts suggest Nabonidus was a contentious person with an abrasive manner. One states that he ordered the beating of a man who had made a seemingly innocuous inquiry about orders relating to the robe outfitting the statue of a god. But the future king was also, some sources report, a skilled diplomat. According to the fifth-century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus, Nabonidus may have negotiated a peace treaty between the Iranian people called the Medes and the Lydians of Anatolia.

EXPAND

Royal Antiquarians

All Neo-Babylonian kings revered Mesopotamia’s deep past, but Nabonidus’ (r. 556–539 B.C.) obsession was particularly acute. “Usurpers often looked to the past for legitimacy,” says Heidelberg University Assyriologist Hanspeter Schaudig. “With no royal lineage, Nabonidus sought to associate himself with great ancient kings.” Tablets recovered throughout Babylonia, in modern-day Iraq, record that Nabonidus sponsored the renovation of temples and encouraged excavations to locate already-ancient artifacts.

One example of Nabonidus’ commitment to exploring the past comes from the sun god Shamash’s temple in the city of Sippar. Archaeologists digging there in 1881 recovered a small stone monument inscribed with archaic Akkadian writing. The text says that King Manishtushu (r. ca. 2269–2255 B.C.) renovated the temple of Shamash and substantially increased its revenues. Two inscribed clay cylinders found by archaeologists alongside the monument describe how it was discovered during a search of old storerooms ordered by Nabonidus.

Below the monument was a clay box containing an 11-inch-high schist object now known as the Sun-God Tablet, along with two clay impressions of the tablet. The tablet celebrates the discovery of an antique clay image of Shamash during the reign of King Nabu-apla-iddina (r. ca. 886–853 B.C.). It also established the ancient privileges of the Shamash priests.

Discovering a monument dating to some 1,700 years before his reign must have been a source of great satisfaction to Nabonidus. But in the 1940s, Assyriologists realized that the “ancient” Akkadian writing was actually a much later Neo-Babylonian forgery. The priests of Shamash seem to have produced the monument in secret, and then presented it as a new discovery from the distant past. It’s possible the image of Shamash whose discovery is described on the Sun-God Tablet was also a forgery. The priests were evidently not above faking antiquities to bolster their privileges. One tip-off to the cruciform monument’s true nature might be found at the end of its almost 350 lines of cuneiform text in the phrase “this is not a lie, it is indeed the truth.”

After his lengthy reign, Nebuchadnezzar II was succeeded by his son-in-law Neriglissar (r. 560–556 B.C.), who sat on the throne for just four years. He in turn was eventually succeeded by his son Labashi-Marduk, who reigned for a mere two weeks before a coup deposed him and placed an already elderly Nabonidus on the throne.

The court records of the Neo-Babylonian kings have not been discovered. Thus, Assyriologists must use other texts, chiefly financial and real estate transactions, to piece together the political events of the day. For example, multiple tablets suggest that Nabonidus’ son Belshazzar seems to have taken over many of Labashi-Marduk’s real estate holdings, making him a prime suspect as the coup’s mastermind. But who helped him put his father on the throne has been an open question. In search of the identities of those who were in Nabonidus’ camp, University of Warsaw Assyriologist Małgorzata Sandowicz recently studied cuneiform tablets detailing real estate transactions that bear the king’s imprimatur.

Sandowicz has found that many men in these records held high titles and were the kind of palace officials one would expect to find in close proximity to the king. A smaller number of men without titles seem to have been Nabonidus’ more intimate associates. Some of them had held positions of power under Nebuchadnezzar II and Neriglissar. They seem to have retained the king’s special favor, suggesting that these companions of Nabonidus could have been critical allies in the coup that installed him as king. Quite a few members of this royal retinue were Aramaeans, an ethnic group whose tribes lived across the Neo-Babylonian Empire. A native of the northern city of Harran, where many Aramaeans lived, Nabonidus may well have been Aramaean himself. At this time, the Aramaeans’ Semitic language, Aramaic, was rapidly displacing Akkadian as the empire’s leading language. “Aramaeans are hard to identify in Babylonian records,” says Sandowicz. “They often managed their affairs in the framework of their own tribal institutions. So the fact that they appear here as associates of the king is significant.” If Nabonidus maintained close links with Aramaeans, that could indicate he might have been interested in keeping a power base outside the official Babylonian system.

Sandowicz notes that just as interesting as who is included in these real estate transactions is who is absent. She has found that those transactions bearing Nabonidus’ stamp of approval include very few names of men belonging to the old, distinguished Babylonian families who had long been associated with the city’s temples. Perhaps, she suggests, there was a power struggle between Nabonidus and these prominent temple families, one that foreshadowed a later religious schism.

In the first three years of his reign, Nabonidus consolidated his rule. His inscriptions proclaim that he campaigned to the west, leading armies to Anatolia and the Levant. He seems to have allied himself with the Persian king Cyrus the Great (r. 559–530 B.C.), whose realm was under control of the Medes when his reign began. Nabonidus encouraged Cyrus to revolt against the Medes, a decision that would eventually come back to haunt him.

During this first phase of his rule, Nabonidus claims to have rebuilt the walls of Babylon, a boast made by nearly every Babylonian king, and to have ordered the rebuilding of temples throughout Mesopotamia. As part of these temple renovations, he was particularly interested in recovering ancient religious cuneiform dedications and statues, and ordered special excavations to hunt for them. He was already making the worship of Sin the centerpiece of his rule. In the second year of his reign, he rededicated the temple of Sin in Ur during a lunar eclipse. He also established his daughter as the main priestess there, evidence of how much he valued his personal connection to the god. Perhaps he wanted to be sure he had a close relative keeping an eye on the priests of the god to whom he was so devoted.

After three years of rule, and without any clear explanation, Nabonidus abandoned Babylon. Leaving his son Belshazzar as regent, he disappeared for a decade to campaign in the wastes of northern Arabia. “We don’t know why he did this, at his age,” says Hanspeter Schaudig, a Heidelberg University Assyriologist. “It would have made much more sense for his son to lead the army and for him to stay at the capital to maintain power and oversee religious rites there.” It is possible that clashes with the priests of Marduk, and perhaps even with his son, impelled Nabonidus to quit Babylon. In his absence, the city’s New Year ceremony and the renewal of the king’s authority went uncelebrated for 10 years, and Marduk languished in the Esagila Temple. Later accounts may exaggerate the extent to which this troubled the Babylonians, but it probably was a source of great anxiety for many in the city.

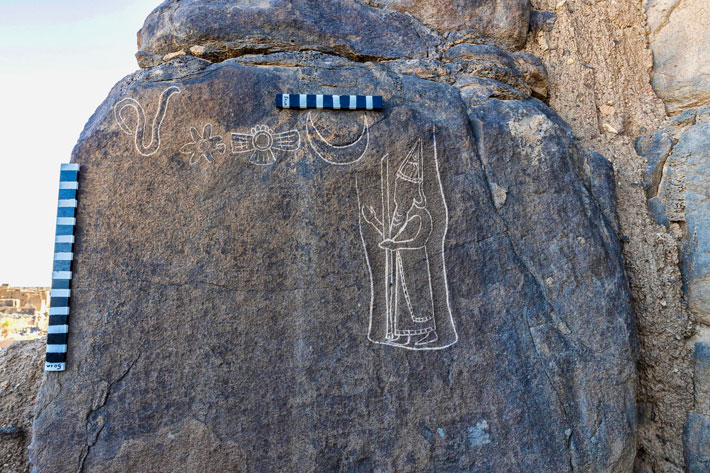

Archaeologists continue to study clues that might explain Nabonidus’ mysterious distant sojourn. A depiction of the king engraved on a rock face almost 400 feet above a canyon floor in what is today Jordan shows that, among other things, he was busy campaigning in the lands to the west occupied by the people known in the Bible as Edomites. University of Barcelona archaeologist Rocío Da Riva recently led a team of climbers who conducted a detailed study of the depiction and the degraded inscription that accompanies it.

The scene, like others depicting Nabonidus, shows him wearing a conical cap and praying to celestial symbols representing three deities: Sin; the goddess Ishtar, represented by a star symbol; and Shamash, the sun god. The inscription accompanying the scene is illegible, but Da Riva believes it commemorates a Babylonian victory over forces occupying an Edomite fortress at the site of Sela, which stood on a mountaintop looming just a few hundred feet above the panel. Da Riva and her team found that the panel was almost impossible to see by anyone except those who walked up an ancient narrow staircase leading to the remains of the fortress at Sela. Seizing such a well-defended position may have been a matter of pride to Nabonidus and his army. Perhaps, suggests Da Riva, they situated the panel to mark the scene of a hard-fought battle as a way of reminding the Edomites of Babylon’s might.

Some 350 miles to southwest of Sela, a Saudi-German team now led by the German Archaeological Institute’s Arnulf Hausleiter has been excavating at the oasis of Tayma since 2005. Before they began, Nabonidus’ presence at the oasis was only known from the literary record. In surveys and excavations, however, they have found structures and inscriptions dating to the period of Nabonidus’ residence there, and a number of artifacts bearing the king’s name. The formal cuneiform inscriptions discovered by the team, including a weathered stela excavated from the site, are largely fragmentary, but are similar to the monuments Nabonidus erected at Babylon. This came as a surprise to Schaudig, who translated the Neo-Babylonian texts found at Tayma. “I thought out in the desert he would have commissioned inscriptions that would have expressed more independent thinking,” says Schaudig. “But they repeat the form of ones from Babylonia.”

A royal inscription identified on a rock face in the summer of 2021 about 200 miles southeast of Tayma near the Saudi Arabian town of Al Hayit provides further evidence of Nabonidus’ activities in the area. The heavily weathered scene is similar to one found in the area in 2012 and shows Nabonidus paying homage to the symbols of Sin, Shamash, and Ishtar, as well as to a fourth symbol that resembles a snake. These two depictions are the only ones of Nabonidus that feature this symbol. It’s possible that the snakelike symbol had special significance for the local Arabian people whom Nabonidus boasts of conquering.

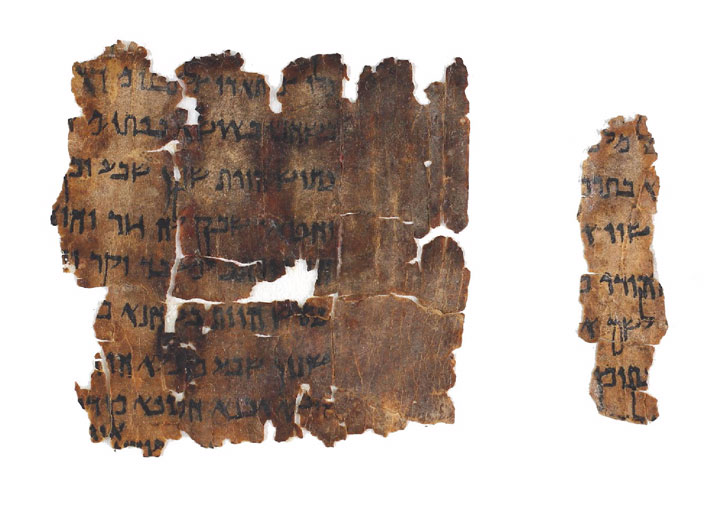

One of the simplest explanations for Nabonidus’ 10-year absence from Babylon is that he was endeavoring to extend the might of the empire to the south and trying to gain control of the valuable trade routes of western Arabia. Other explanations offered by ancient sources—apart from the idea that the king was simply mad—include the suggestion that Nabonidus suffered from some ailment he hoped time in the desert might cure. Parchment fragments of the Dead Sea Scrolls discovered in the Qumran caves of the West Bank offer a version of this story. These fragments preserve a literary work known as “The Prayer of Nabonidus,” which may have originally been composed by Judeans living in Babylon. Its author or authors suggest the king suffered from a severe skin condition and fled Babylon, perhaps to avoid polluting its sacred temples with his unclean body. Once in the desert, he prayed to the god of the Judeans for relief. The source of this story could have been an urban legend that arose in Babylon during Nabonidus’ absence and may have also helped inspire the account of the mad king in the Book of Daniel. Perhaps it was whispered that the king fled to the desert to pray to Sin, the moon god, for a cure to a leprosy-like malady. Other Babylonian works suggest the god, by virtue of the moon’s pitted surface, was able to cure diseases of the skin. Whether or not he had an illness that was relieved by his stay in Arabia, by 543 B.C. Nabonidus had returned to Babylon with his devotion to Sin undiminished.

EXPAND

The Reign of Babylon's God King

Cuneiform texts make clear that the Neo-Babylonian king Nabonidus (r. 556–539 B.C.) elevated the status of the moon god Sin at the expense of Babylon’s long-time patron deity Marduk, who was the king of all Mesopotamian deities. Nabonidus’ own inscriptions record that he clashed with the powerful priests of Marduk, and compositions written after the king was deposed by the Persian ruler Cyrus the Great (r. 559–530 B.C.) claim that the people of Babylon were scandalized by Nabonidus’ treatment of the god. If the texts are to be believed, Babylonians were especially dismayed that Nabonidus failed to celebrate the New Year rituals that were central to Marduk’s cult and to maintaining Babylon’s role as Mesopotamia’s chief city. Cyrus is said to have restored Marduk to his rightful place, but it’s likely people in other ancient Mesopotamian cities such Nippur may have recalled a time when Marduk himself was an interloper among the gods. “We need to remember that Marduk wasn’t always the great deity he was known as in the Neo-Babylonian period,” says Heidelberg University Assyriologist Hanspeter Schaudig. “He himself was once a god-killer.”

In the third millennium B.C., Babylon was a small, obscure city. Marduk was a minor deity with equally obscure origins who seems to have been associated with agriculture and canals, and whose symbol was a spade. During this period, Nippur was Mesopotamia’s most sacred city, and its god, Enlil, wielded ultimate divine power. But in the second millennium B.C., especially during the reign of Hammurabi (r. ca. 1792–1750 B.C.), Marduk became an ever more consequential god. As Babylon’s influence grew, he assumed the powers and name of Addu, a storm god who was the patron deity of the city of Halab, modern-day Aleppo.

Toward the end of his reign, Hammurabi defeated the ruler of the city of Eshnunna, which had been allied with the Elamite people who lived in modern-day Iran and posed a constant threat to Babylonia. At the same time, cuneiform texts celebrated Marduk’s victory over Eshnunna’s patron god Tishpak. Marduk then appropriated Tishpak’s chief symbol, the lion-dragon hybrid beast known as mušhuššu, or “furious snake,” with whom he would be associated for the rest of Babylonian history. Depictions of mušhuššu that decorated the city’s famed Ishtar Gate, which was built more than 1,000 years later, still commemorated Marduk’s victory over Tishpak, and Babylon’s over an important ally of Elam.

By the twelfth century B.C., Marduk played a central role in an updated Mesopotamian creation story known as the Enuma Elish, which later cuneiform tablets preserve in many versions. The standard account of this narrative legitimized the god’s position as ruler of the divine pantheon once headed by Enlil and explains how Babylon supplanted Nippur as Mesopotamia’s most important religious center. In the creation myth, Marduk is a young warrior god and the only deity willing to do combat with Tiamat, the goddess of the sea and embodiment of chaos. In return for facing Tiamat, the gods agree to make Marduk king of the gods. Upon killing the goddess, Marduk claims his throne and brings order to the cosmos and creates the world. He makes Babylon the first city and home to his Esagila temple, where Marduk lived in the form of his sacred statue. This version of the Enuma Elish completely ignores Enlil and his sacred city of Nippur, erasing Babylon’s rival from the creation story.

Babylon’s status as Mesoptomia’s chief city waxed and waned, and it was sometimes captured by outside powers, events Marduk’s followers needed to account for. One text known as the Marduk Prophecy recounts how Babylonians sometimes angered the god. Their city was consequently then seized by enemies such as the Hittites from Anatolia and Elamites, each of whom “godnapped” Marduk by capturing his sacred statue and taking it back to their respective capitals. The prophecy refers to these events as the travels of Marduk, as if the god chose to be borne away to foreign lands. Those second millenium B.C. sojourns were brought to an end by the Babylonian king Nebuchadnezar I (r. ca. 1125–1104 B.C.), during whose reign the Enuma Elish may have first been written down. The king sacked the Elamite city of Susa, reclaimed Marduk’s statue, and brought it back home to Babylon, once again establishing it as Mesopotamia’s capital of both earthly and cosmic rule.

In the last years of his reign, Nabonidus commissioned a series of stelas and other inscriptions that emphasized the primacy of Sin. Some of the most vivid examples of his devotion to the moon god are inscriptions on stelas that celebrate his restoration of the god’s temple in Harran and record the autobiography of Nabonidus’ mother Adad-guppi, who is said to have died at the age of 102, just before the end of her son’s reign. The inscriptions describe her service to the moon god, while at the same time taking the priests of Babylon to task for their alleged disrespect toward Sin. Nowhere do they mention Marduk. Instead, Nabonidus’ inscriptions suggest that Sin was on the rise, perhaps as the one god who could unite the diverse and far-flung peoples living under Babylonian rule. “The moon was worshipped everywhere,” says Beaulieu. “In the deserts where Nabonidus had just spent ten years, in his hometown to the north, and in the Levant.”

Documents from this time also suggest that Nabonidus was threatened by the rising power of Cyrus, who had by then bested the Medes and supplanted them as Babylon’s main rival. Some of these documents record that Nabonidus ordered statues of the patron gods of all the empire’s chief cities to be brought to Babylon for safekeeping as a precaution against a Persian invasion. Three cuneiform texts, the Verse Account of Nabonidus, the Nabonidus Chronicle, and the Cyrus Cylinder, give accounts of the last days of Nabonidus’ reign that are not generous to the king. They follow the march of Cyrus’ army into Babylonia and the entry of his general Gubaru into Babylon itself in 539 B.C. “It only took two weeks,” says Beaulieu. “It was probably the swiftest collapse of an empire in history.” According to these accounts, the people of Babylon were fed up with Nabonidus’ rule and welcomed the Persians with open arms. The texts say that Cyrus restored Marduk to his rightful status as Babylon’s most important deity and that Nabonidus was sent into exile.

In these Persian period cuneiform accounts, Nabonidus’ apostasy is invoked as an explanation for the fall of the city. They claim that Babylonians considered Nabonidus an utter failure as a ruler. But at least two rebel leaders who rose up against the Persians in the century after Babylon’s fall styled themselves as “sons of Nabonidus,” suggesting that the king’s memory still enjoyed some goodwill in the city. Perhaps some even remembered Nabonidus not as a mad king, an absent ruler, or a moon-god fanatic, but simply as a Babylonian trying to reinvent his empire to ensure its survival, and as a man who ran out of time.