Features

The Philistine Age

By ILAN BEN ZION

Tuesday, July 12, 2022

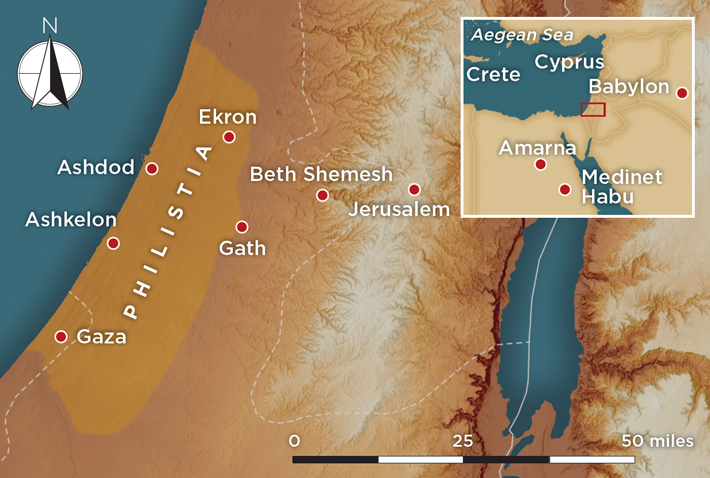

In the heat of the day, a glint off the Mediterranean is just visible from the top of a mound known as Tell es-Safi that rises some 300 feet above Israel’s coastal plain. For generations, scholars believed that the stretch of Mediterranean coast west of Tell es-Safi was once the landing point of multiple invasions by the Israelites’ dreaded nemeses, the Philistines. First emerging in the southern Levant around 3,200 years ago, the Philistines were long thought to have been descendants of invading groups that scholars refer to as the “Sea Peoples.” In the twilight of the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1550–1200 B.C.), these groups raided Egypt and conquered the cities of the Semitic Canaanite people who lived on the coast of what is now Israel and the Palestinian territories. A final wave of Philistine invasions was thought to have reached the coast of Canaan early in the reign of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses III (r. ca. 1184–1153 B.C.), around 1175 B.C. The ruins of Gath, a Canaanite center that became the Philistines’ mightiest city, now lie beneath Tell es-Safi, which means “white hill” in Arabic. The mound’s white chalk cliffs, which overlook fertile farmland, inspired the Crusaders to name the castle they built there in the twelfth century A.D. Blanche Garde or White Fortress. Until the war that followed Israel’s founding in 1948, the tell was home to a small Palestinian village whose ruins are now overgrown with thorns.

In the heat of the day, a glint off the Mediterranean is just visible from the top of a mound known as Tell es-Safi that rises some 300 feet above Israel’s coastal plain. For generations, scholars believed that the stretch of Mediterranean coast west of Tell es-Safi was once the landing point of multiple invasions by the Israelites’ dreaded nemeses, the Philistines. First emerging in the southern Levant around 3,200 years ago, the Philistines were long thought to have been descendants of invading groups that scholars refer to as the “Sea Peoples.” In the twilight of the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1550–1200 B.C.), these groups raided Egypt and conquered the cities of the Semitic Canaanite people who lived on the coast of what is now Israel and the Palestinian territories. A final wave of Philistine invasions was thought to have reached the coast of Canaan early in the reign of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses III (r. ca. 1184–1153 B.C.), around 1175 B.C. The ruins of Gath, a Canaanite center that became the Philistines’ mightiest city, now lie beneath Tell es-Safi, which means “white hill” in Arabic. The mound’s white chalk cliffs, which overlook fertile farmland, inspired the Crusaders to name the castle they built there in the twelfth century A.D. Blanche Garde or White Fortress. Until the war that followed Israel’s founding in 1948, the tell was home to a small Palestinian village whose ruins are now overgrown with thorns.

Gath was one of five cities known as the Philistine Pentapolis, which thrived during the Iron Age (ca. 1200–539 B.C.). Until archaeologists began to excavate the cities of the Pentapolis, also known as Philistia, the Philistines were largely known through the work of the scribes who first began to write the books of the Hebrew Bible hundreds of years after the Sea Peoples reached the Levant. These scribes cast the Philistines as the Israelites’ uncircumcised, pagan archenemies, who fought against some of the Bible’s most prominent figures. According to the Bible, the Israelite judge Samson slew 1,000 Philistine warriors with the jawbone of an ass and pulled down the pillars of a temple to Dagon, the principal Philistine god. After the Philistines had captured the Ark of the Covenant, Saul, Israel’s first king, fell on his sword rather than be taken captive. Saul’s son-in-law and eventual heir, King David, dueled with the Philistine hero Goliath of Gath and felled the giant with a slingshot. The Bible’s pejorative depiction of the Philistines has so pervaded Western culture that, more than 3,000 years on, “philistine” remains a byword for an unsophisticated person indifferent or hostile to artistic and intellectual pursuits.

Gath was one of five cities known as the Philistine Pentapolis, which thrived during the Iron Age (ca. 1200–539 B.C.). Until archaeologists began to excavate the cities of the Pentapolis, also known as Philistia, the Philistines were largely known through the work of the scribes who first began to write the books of the Hebrew Bible hundreds of years after the Sea Peoples reached the Levant. These scribes cast the Philistines as the Israelites’ uncircumcised, pagan archenemies, who fought against some of the Bible’s most prominent figures. According to the Bible, the Israelite judge Samson slew 1,000 Philistine warriors with the jawbone of an ass and pulled down the pillars of a temple to Dagon, the principal Philistine god. After the Philistines had captured the Ark of the Covenant, Saul, Israel’s first king, fell on his sword rather than be taken captive. Saul’s son-in-law and eventual heir, King David, dueled with the Philistine hero Goliath of Gath and felled the giant with a slingshot. The Bible’s pejorative depiction of the Philistines has so pervaded Western culture that, more than 3,000 years on, “philistine” remains a byword for an unsophisticated person indifferent or hostile to artistic and intellectual pursuits.

Finds from limited excavations during the early twentieth century pointed archaeologists to the Aegean as the Philistines’ original homeland. The conquerors, they imagined, were Mycenaeans, members of the Late Bronze Age culture of ancient Greece remembered in the epic poems of the Trojan War, Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Since the 1990s, archaeologists have extensively excavated four of the five cities of the Philistine Pentapolis: Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron, and Gath. Only Gaza, which is located beneath the modern Palestinian city of the same name, remains unexcavated. These digs, particularly the long-term excavations of the ruins of Gath beneath Tell es-Safi, have helped archaeologists tell a more nuanced story about the origins of the Philistines, which may lie in a series of mass migrations rather than waves of conquest. “Understanding the Philistines as this singular, unified migratory group that came from somewhere in Greece, landed on the coast, and conquered the Canaanite cities no longer makes sense,” says Bar-Ilan University archaeologist Aren Maeir, who directs the Tell es-Safi excavations.

Journeys of the Pyramid Builders

By DANIEL WEISS

Friday, June 10, 2022

On a summer afternoon around 4,600 years ago, near the end of the reign of the pharaoh Khufu, a boat crewed by some 40 workers headed downstream on the Nile toward the Giza Plateau. The vessel, whose prow was emblazoned with a uraeus, the stylized image of an upright cobra worn by pharaohs as a head ornament, was laden with large limestone blocks being transported from the Tura quarries on the eastern side of the Nile. Under the direction of their overseer, known as Inspector Merer, the team steered the boat west toward the plateau, passing through a gateway between a pair of raised mounds called the Ro-She Khufu, the Entrance to the Lake of Khufu. This lake was part of a network of artificial waterways and canals that had been dredged to allow boats to bring supplies right up to the plateau’s edge.

On a summer afternoon around 4,600 years ago, near the end of the reign of the pharaoh Khufu, a boat crewed by some 40 workers headed downstream on the Nile toward the Giza Plateau. The vessel, whose prow was emblazoned with a uraeus, the stylized image of an upright cobra worn by pharaohs as a head ornament, was laden with large limestone blocks being transported from the Tura quarries on the eastern side of the Nile. Under the direction of their overseer, known as Inspector Merer, the team steered the boat west toward the plateau, passing through a gateway between a pair of raised mounds called the Ro-She Khufu, the Entrance to the Lake of Khufu. This lake was part of a network of artificial waterways and canals that had been dredged to allow boats to bring supplies right up to the plateau’s edge.

As the boatmen approached their docking station, they could see Khufu’s Great Pyramid, called Akhet Khufu, or the Horizon of Khufu, soaring into the sky. At this point in Khufu’s reign (r. ca. 2633–2605 B.C.), the pyramid would have been essentially complete, encased in gleaming white limestone blocks of the sort the boat carried. At the edge of the water, perched on a massive limestone foundation, loomed Khufu’s valley temple, known as Ankhu Khufu, or Khufu Lives, which was connected to the pyramid by a half-mile-long causeway. When the pharaoh died, his body would be taken to the valley temple and then carried to the pyramid for burial. Nearby stood a royal palace, archives, granary, and workers’ barracks.

As the boatmen approached their docking station, they could see Khufu’s Great Pyramid, called Akhet Khufu, or the Horizon of Khufu, soaring into the sky. At this point in Khufu’s reign (r. ca. 2633–2605 B.C.), the pyramid would have been essentially complete, encased in gleaming white limestone blocks of the sort the boat carried. At the edge of the water, perched on a massive limestone foundation, loomed Khufu’s valley temple, known as Ankhu Khufu, or Khufu Lives, which was connected to the pyramid by a half-mile-long causeway. When the pharaoh died, his body would be taken to the valley temple and then carried to the pyramid for burial. Nearby stood a royal palace, archives, granary, and workers’ barracks.

After offloading their cargo, the men anchored their boat in the lake alongside dozens—if not hundreds—of other boats and barges that had brought a variety of materials necessary to complete construction of the pyramid complex: granite beams from Aswan, gypsum and basalt from the Fayum, and timber from Lebanon. Also arriving by boat were workers from across Egypt and cattle from the Nile Delta to feed them. As the sun set and twilight deepened, hearth fires twinkled on land and on many of the boats. Merer and his men settled in for a night’s sleep, after which they would head back to the quarries to pick up another load of limestone blocks. They would make two or three such round trips in the next 10 days.

The Great Pyramid originally measured some 481 feet tall and 755 feet on a side. It was composed of an astounding 91 million cubic feet of stone—roughly the amount it would take to fill a football stadium to the top tier of seats. Although nowhere to be seen in the finished product, massive amounts of copper were essential to building the monument. Copper picks were used to quarry the stone. Copper saws were used to cut it, and experiments have shown that an inch of metal was lost from blades for every one to four inches of stone cut. While preparing the stone blocks for use in the pyramid, workers smoothed their surfaces with copper chisels the width of an index finger. The immense quantity of copper consumed by the construction project—not to mention the other pyramids and monumental buildings that preceded and followed it—led to an urgent search for sources of the metal.

The Great Pyramid originally measured some 481 feet tall and 755 feet on a side. It was composed of an astounding 91 million cubic feet of stone—roughly the amount it would take to fill a football stadium to the top tier of seats. Although nowhere to be seen in the finished product, massive amounts of copper were essential to building the monument. Copper picks were used to quarry the stone. Copper saws were used to cut it, and experiments have shown that an inch of metal was lost from blades for every one to four inches of stone cut. While preparing the stone blocks for use in the pyramid, workers smoothed their surfaces with copper chisels the width of an index finger. The immense quantity of copper consumed by the construction project—not to mention the other pyramids and monumental buildings that preceded and followed it—led to an urgent search for sources of the metal.

|

Sidebar:

|

Giza's Layout

|

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Digs & Discoveries

Save the Dates

Spice Hunters

Suspicious Silver

A Civil War Bomb

The Great Maize Migration

Mummy Makers

Dignity of the Dead

Sailing in Sumer

Speak, Memories

The Maya Count Begins

Hail to the Chief

Made in China

Off the Grid

Around the World

Notre Dame’s dignitaries, Bronze Age daggers, the world’s biggest quake, a lost snowshoe, and 50,000-year-old Australians

Artifact

A portable connection

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Maeir and many of his colleagues suggest that the Philistines were an eclectic and multiethnic group of migrants, not a uniform horde of invaders. He believes it’s likely they hailed from various locations around the eastern Mediterranean and moved to the Levant over many decades between the late thirteenth and mid-twelfth centuries B.C. They settled, mostly peaceably, among the local Canaanites, creating a distinct hybrid culture that endured for much of the Iron Age. “What we’ve learned about Philistine culture at Gath,” Maeir says, “is that the process of its origins, formation, transformation, and development is much more complex than was originally thought.”

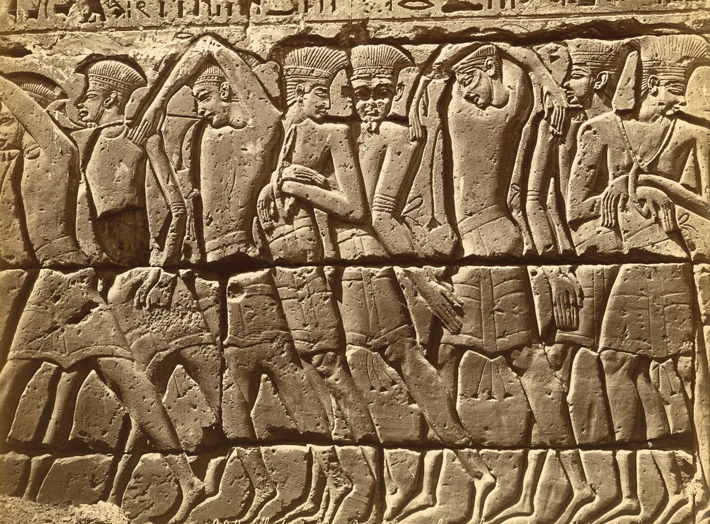

Maeir and many of his colleagues suggest that the Philistines were an eclectic and multiethnic group of migrants, not a uniform horde of invaders. He believes it’s likely they hailed from various locations around the eastern Mediterranean and moved to the Levant over many decades between the late thirteenth and mid-twelfth centuries B.C. They settled, mostly peaceably, among the local Canaanites, creating a distinct hybrid culture that endured for much of the Iron Age. “What we’ve learned about Philistine culture at Gath,” Maeir says, “is that the process of its origins, formation, transformation, and development is much more complex than was originally thought.” Inscriptions on the walls of Ramesses III’s mortuary temple at Medinet Habu tell of battles in the early twelfth century B.C. against the Sea Peoples, who are depicted on reliefs engaging the Egyptians in naval combat. These warriors wear feathered and horned helmets and fight from ships whose prows are decorated with carvings of birds’ heads. Among the names describing the Sea Peoples inscribed at Medinet Habu is Peleset, which nineteenth-century scholars first linked to the biblical Philistines. Biblical texts offered early researchers further clues about who the Philistines were. Their leaders are referred to by the title seren, which scholars once believed may be related to the Greek term tyrannos, or ruler. According to the Bible, the Philistines arrived from the island of Caphtor, which may be the Greek island of Crete.

Inscriptions on the walls of Ramesses III’s mortuary temple at Medinet Habu tell of battles in the early twelfth century B.C. against the Sea Peoples, who are depicted on reliefs engaging the Egyptians in naval combat. These warriors wear feathered and horned helmets and fight from ships whose prows are decorated with carvings of birds’ heads. Among the names describing the Sea Peoples inscribed at Medinet Habu is Peleset, which nineteenth-century scholars first linked to the biblical Philistines. Biblical texts offered early researchers further clues about who the Philistines were. Their leaders are referred to by the title seren, which scholars once believed may be related to the Greek term tyrannos, or ruler. According to the Bible, the Philistines arrived from the island of Caphtor, which may be the Greek island of Crete. Early twentieth-century archaeologists made a number of discoveries that seemed to reinforce biblical and Egyptian descriptions of the Philistines. Excavations at Ashkelon and Beth Shemesh—an Israelite city east of Gath mentioned in the Book of Judges as the location to which the Philistines returned the stolen Ark of the Covenant—unearthed early Philistine ceramics that closely resemble types of Mycenaean pottery found throughout the Aegean. These early Philistine wares feature geometric patterns in red and black and are sometimes decorated with depictions of birds’ heads akin to those in the Medinet Habu reliefs. The Mycenaeans are known to have used these vessels for drinking and feasting, and the Philistines likely used them in the same way. Although these ceramic vessels provided the first firm connection between the Philistines and the Aegean world, later examinations of other pieces of early Philistine pottery revealed that they were crafted from local Canaanite clay. From the beginning, then, Philistines were adapting their culture to local conditions.

Early twentieth-century archaeologists made a number of discoveries that seemed to reinforce biblical and Egyptian descriptions of the Philistines. Excavations at Ashkelon and Beth Shemesh—an Israelite city east of Gath mentioned in the Book of Judges as the location to which the Philistines returned the stolen Ark of the Covenant—unearthed early Philistine ceramics that closely resemble types of Mycenaean pottery found throughout the Aegean. These early Philistine wares feature geometric patterns in red and black and are sometimes decorated with depictions of birds’ heads akin to those in the Medinet Habu reliefs. The Mycenaeans are known to have used these vessels for drinking and feasting, and the Philistines likely used them in the same way. Although these ceramic vessels provided the first firm connection between the Philistines and the Aegean world, later examinations of other pieces of early Philistine pottery revealed that they were crafted from local Canaanite clay. From the beginning, then, Philistines were adapting their culture to local conditions. Other discoveries have helped Maeir and his team develop a more nuanced take on Philistine culture. Among their most important finds is a ninth-century B.C. two-horned altar, which combines decorative elements from the Levant with those known from Cyprus and the Aegean. It is the oldest such altar in Philistia. The team also found a sherd bearing inscriptions written in Canaanite script with two names that are close to Goliath, suggesting that the now-famous name may have been common in Philistia. At the same time, they have discovered copious amounts of Canaanite pottery and other artifacts dating to the earliest stages of the Philistine period. The picture of Philistine Gath emerging from recent excavations, says Maeir, is one of a vibrant metropolis where migrants from around the Mediterranean lived cheek-by-jowl with Canaanites. For several generations, these two distinct cultures coexisted before combining into one.

Other discoveries have helped Maeir and his team develop a more nuanced take on Philistine culture. Among their most important finds is a ninth-century B.C. two-horned altar, which combines decorative elements from the Levant with those known from Cyprus and the Aegean. It is the oldest such altar in Philistia. The team also found a sherd bearing inscriptions written in Canaanite script with two names that are close to Goliath, suggesting that the now-famous name may have been common in Philistia. At the same time, they have discovered copious amounts of Canaanite pottery and other artifacts dating to the earliest stages of the Philistine period. The picture of Philistine Gath emerging from recent excavations, says Maeir, is one of a vibrant metropolis where migrants from around the Mediterranean lived cheek-by-jowl with Canaanites. For several generations, these two distinct cultures coexisted before combining into one. The 2013 discovery of a cemetery at Ashkelon, the first large burial ground to be excavated at one of the cities of the Philistine Pentapolis, has helped bolster Master’s view. This cemetery contained some 200 burials dating to the Philistine period in which individuals were interred separately. This is unlike Canaanite funerary practices in which the dead were cremated or buried collectively in pits or tombs. Genetic analysis of these remains, says Master, supports Egyptian accounts of the Philistines’ origins. He was part of a team that analyzed the DNA of 10 individuals found in the Ashkelon cemetery: three dating from the Bronze Age, four from the Early Iron Age, and three dating to the tenth to ninth century B.C. The team found that DNA sampled from the Early Iron Age burials had a European genetic component that set the people apart from the local Bronze Age Canaanite population and supports the idea that the Philistines originated in Crete.

The 2013 discovery of a cemetery at Ashkelon, the first large burial ground to be excavated at one of the cities of the Philistine Pentapolis, has helped bolster Master’s view. This cemetery contained some 200 burials dating to the Philistine period in which individuals were interred separately. This is unlike Canaanite funerary practices in which the dead were cremated or buried collectively in pits or tombs. Genetic analysis of these remains, says Master, supports Egyptian accounts of the Philistines’ origins. He was part of a team that analyzed the DNA of 10 individuals found in the Ashkelon cemetery: three dating from the Bronze Age, four from the Early Iron Age, and three dating to the tenth to ninth century B.C. The team found that DNA sampled from the Early Iron Age burials had a European genetic component that set the people apart from the local Bronze Age Canaanite population and supports the idea that the Philistines originated in Crete.  University of Melbourne archaeologist Louise Hitchcock, who directed excavations in a residential district at Tell es-Safi, remains cautious about the Ashkelon DNA findings. She points to the study’s small sample size. “I don’t think you can say they were Philistine based on their DNA,” Hitchcock says, “but you can based on their full realm of material culture.” In recent years, finds from Gath, Ekron, and Ashkelon have all suggested that Philistine culture was eclectic and had parallels in Late Bronze Age cultures from throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Researchers have analyzed dog bones from Philistine sites that suggest that, like pigs, dogs were part of the Philistine diet, as they were across the Aegean and Anatolia. Nonlocal flora from around the Mediterranean, including sycamore, poppy, and cumin, first appeared in the Levant at Philistine sites. Some finds, such as circular pebbled hearths similar to those found in the center of homes in Greece and Cyprus, cult objects such as figurines of goddesses with their arms raised in a shape resembling the Greek letter psi (Ψ), and Cypriot-style notched cow scapulas possibly used in soothsaying, underscore that the Philistines were connected to the ancient Greek world. At the same time, a seated female figurine discovered at Ashdod featuring an unusual combination of Aegean and Levantine styles demonstrates the rich combination of cultural influences that permeated the world of the Philistines.

University of Melbourne archaeologist Louise Hitchcock, who directed excavations in a residential district at Tell es-Safi, remains cautious about the Ashkelon DNA findings. She points to the study’s small sample size. “I don’t think you can say they were Philistine based on their DNA,” Hitchcock says, “but you can based on their full realm of material culture.” In recent years, finds from Gath, Ekron, and Ashkelon have all suggested that Philistine culture was eclectic and had parallels in Late Bronze Age cultures from throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Researchers have analyzed dog bones from Philistine sites that suggest that, like pigs, dogs were part of the Philistine diet, as they were across the Aegean and Anatolia. Nonlocal flora from around the Mediterranean, including sycamore, poppy, and cumin, first appeared in the Levant at Philistine sites. Some finds, such as circular pebbled hearths similar to those found in the center of homes in Greece and Cyprus, cult objects such as figurines of goddesses with their arms raised in a shape resembling the Greek letter psi (Ψ), and Cypriot-style notched cow scapulas possibly used in soothsaying, underscore that the Philistines were connected to the ancient Greek world. At the same time, a seated female figurine discovered at Ashdod featuring an unusual combination of Aegean and Levantine styles demonstrates the rich combination of cultural influences that permeated the world of the Philistines.

These Late Bronze Age pirates may have spoken different languages and chosen particular symbols that bound them together as a group in the way many early modern pirates rallied to the Jolly Roger. The Aegean-style drinking and feasting ware found at Philistine sites, Maeir and Hitchcock suggest, may have served as just such a symbol. They point out that feasting was an important feature of Bronze Age society and played a central role in the culture of more recent pirates as well. It’s also possible that the feathered and horned helmets and the birds’ head prows depicted on the Medinet Habu reliefs served as potent symbols that a diverse group of pirates could rally around. The scholars further suggest that seren, the word describing the leaders of the Peleset chiefs on the Medinet Habu reliefs, may not come from the Greek word tyrannos after all. Instead, they believe it may be related to the word tarwanis used by the Luwian people of southern Anatolia to describe warlords. Perhaps it was these Bronze Age Blackbeards who became the first Philistines.

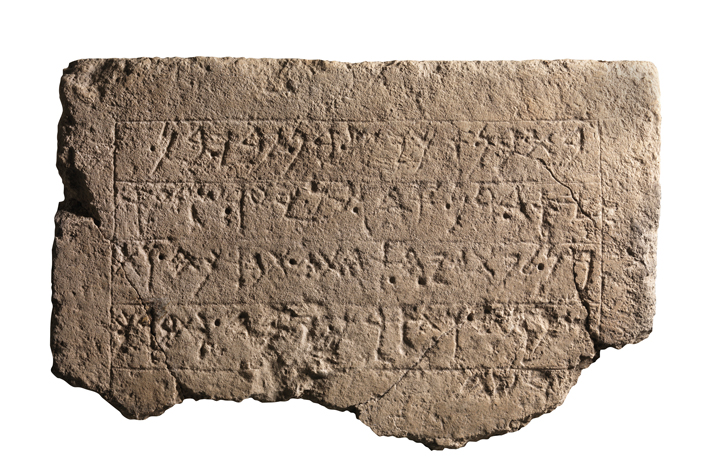

These Late Bronze Age pirates may have spoken different languages and chosen particular symbols that bound them together as a group in the way many early modern pirates rallied to the Jolly Roger. The Aegean-style drinking and feasting ware found at Philistine sites, Maeir and Hitchcock suggest, may have served as just such a symbol. They point out that feasting was an important feature of Bronze Age society and played a central role in the culture of more recent pirates as well. It’s also possible that the feathered and horned helmets and the birds’ head prows depicted on the Medinet Habu reliefs served as potent symbols that a diverse group of pirates could rally around. The scholars further suggest that seren, the word describing the leaders of the Peleset chiefs on the Medinet Habu reliefs, may not come from the Greek word tyrannos after all. Instead, they believe it may be related to the word tarwanis used by the Luwian people of southern Anatolia to describe warlords. Perhaps it was these Bronze Age Blackbeards who became the first Philistines. According to the Bible, once-mighty Gath fell in the ninth century B.C. to King Hazael of the Aramaeans, a Semitic people who dominated what is now Syria. Maeir and his team have found siege works encircling Tell es-Safi that date to this time and suggest that the people of Gath faced a protracted conflict. Though the Philistines abandoned Gath, their distinct culture lasted in some form in the other cities of the Pentapolis for almost 300 years. The discovery of a seventh-century B.C. royal inscription at Ekron written in Canaanite but including the Philistine name Achish is clear evidence that the Philistine presence endured well after the fall of Gath.

According to the Bible, once-mighty Gath fell in the ninth century B.C. to King Hazael of the Aramaeans, a Semitic people who dominated what is now Syria. Maeir and his team have found siege works encircling Tell es-Safi that date to this time and suggest that the people of Gath faced a protracted conflict. Though the Philistines abandoned Gath, their distinct culture lasted in some form in the other cities of the Pentapolis for almost 300 years. The discovery of a seventh-century B.C. royal inscription at Ekron written in Canaanite but including the Philistine name Achish is clear evidence that the Philistine presence endured well after the fall of Gath. Some copper was extracted from the Eastern Desert, between the Nile Valley and the Red Sea, but the major copper mines were across the sea in the southern portion of the Sinai Peninsula. The most efficient way to access these mines was by boat. Until just over a decade ago, the earliest known Red Sea harbor was at Ayn Sukhna, which was excavated starting in 2001 by a team led by Egyptologist Pierre Tallet of the University of Paris-Sorbonne. The harbor at Ayn Sukhna appears to have been used intermittently for more than a millennium to access the Sinai, starting during the reign of Khafre (r. ca. 2597–2573 B.C.), Khufu’s son. Then, in 2008, Tallet’s team relocated a previously known but little understood coastal site at Wadi el-Jarf, some 60 miles south of Ayn Sukhna, and found that it had served as a harbor for around 50 to 70 years in the 4th Dynasty (ca. 2675–2545 B.C.), including the reign of Khufu. It is the earliest known harbor in the world.

Some copper was extracted from the Eastern Desert, between the Nile Valley and the Red Sea, but the major copper mines were across the sea in the southern portion of the Sinai Peninsula. The most efficient way to access these mines was by boat. Until just over a decade ago, the earliest known Red Sea harbor was at Ayn Sukhna, which was excavated starting in 2001 by a team led by Egyptologist Pierre Tallet of the University of Paris-Sorbonne. The harbor at Ayn Sukhna appears to have been used intermittently for more than a millennium to access the Sinai, starting during the reign of Khafre (r. ca. 2597–2573 B.C.), Khufu’s son. Then, in 2008, Tallet’s team relocated a previously known but little understood coastal site at Wadi el-Jarf, some 60 miles south of Ayn Sukhna, and found that it had served as a harbor for around 50 to 70 years in the 4th Dynasty (ca. 2675–2545 B.C.), including the reign of Khufu. It is the earliest known harbor in the world.

By studying these papyri and examining their findings at Wadi el-Jarf and on the Sinai Peninsula, Tallet and his colleagues have gained new insight into the state apparatus and the workforce that helped produce some of the world’s most awe-inspiring monuments. “It seems that at the beginning of the Fourth Dynasty, the Egyptians were trying to do everything big,” says Tallet. “Everything they were doing at the time is oversized. It’s the case at the Giza Plateau with the pyramids, and it’s the case at Wadi el-Jarf as well.”

By studying these papyri and examining their findings at Wadi el-Jarf and on the Sinai Peninsula, Tallet and his colleagues have gained new insight into the state apparatus and the workforce that helped produce some of the world’s most awe-inspiring monuments. “It seems that at the beginning of the Fourth Dynasty, the Egyptians were trying to do everything big,” says Tallet. “Everything they were doing at the time is oversized. It’s the case at the Giza Plateau with the pyramids, and it’s the case at Wadi el-Jarf as well.” When the team first arrived at the site, they found that the entrances to the 31 storage galleries had been sealed with large limestone blocks. Inside almost all the galleries they have explored, which range in length from 50 to 100 feet, the archaeologists have uncovered large quantities of cedar, pine, and rope fragments, indicating that, as at Ayn Sukhna, the galleries were used to store boats during those parts of the year when dangerous weather conditions made the Red Sea unnavigable. Many of the galleries were also filled with ceramic storage jars, which have been key to helping Tallet’s team understand how the port worked. Given that the closest source of fresh water is a spring around six miles inland from the galleries, the researchers believe the eight-gallon jars were used to store water for harbor workers, as well as to transport goods to and from the Sinai. A number of broken jars have been found in the water near the shore. Still more have been discovered at a fortress known as el-Markha some 30 miles across the Red Sea from Wadi el-Jarf, evidence that it was the destination for expeditions from the harbor and likely served as a base for Sinai mining operations.

When the team first arrived at the site, they found that the entrances to the 31 storage galleries had been sealed with large limestone blocks. Inside almost all the galleries they have explored, which range in length from 50 to 100 feet, the archaeologists have uncovered large quantities of cedar, pine, and rope fragments, indicating that, as at Ayn Sukhna, the galleries were used to store boats during those parts of the year when dangerous weather conditions made the Red Sea unnavigable. Many of the galleries were also filled with ceramic storage jars, which have been key to helping Tallet’s team understand how the port worked. Given that the closest source of fresh water is a spring around six miles inland from the galleries, the researchers believe the eight-gallon jars were used to store water for harbor workers, as well as to transport goods to and from the Sinai. A number of broken jars have been found in the water near the shore. Still more have been discovered at a fortress known as el-Markha some 30 miles across the Red Sea from Wadi el-Jarf, evidence that it was the destination for expeditions from the harbor and likely served as a base for Sinai mining operations. The harbor at Wadi el-Jarf must have been a hive of carefully coordinated activity. Boats would have been carried around 100 miles across the desert from the Nile Valley in parts and assembled at the site. Mine workers, along with others delivering food and supplies such as wood to fuel the copperprocessing furnaces, would also have made the trek. Trains of donkeys would have constantly filed back and forth from the harbor to fetch water from the inland spring. And boats would have shuttled to and fro across the Red Sea, sending workers and supplies and returning with copper. Overlooking the site was a pair of hilltop camps situated above the storage galleries. These camps have yet to be excavated, but the researchers believe they were a control point where overseers monitored the harbor and could observe anyone approaching on desert trails. “Managing the site was an incredible logistical operation,” says Gregory Marouard, an archaeologist at Yale University who is part of Tallet’s team. “It took at least seven days to cross the desert from the Nile Valley, and they had to bring everything with them. There were also probably several different groups of workers involved, doing different jobs. And it was a seasonal operation, so when they organized a new expedition, people had to come to reopen the galleries, rebuild the boats, and so on.”

The harbor at Wadi el-Jarf must have been a hive of carefully coordinated activity. Boats would have been carried around 100 miles across the desert from the Nile Valley in parts and assembled at the site. Mine workers, along with others delivering food and supplies such as wood to fuel the copperprocessing furnaces, would also have made the trek. Trains of donkeys would have constantly filed back and forth from the harbor to fetch water from the inland spring. And boats would have shuttled to and fro across the Red Sea, sending workers and supplies and returning with copper. Overlooking the site was a pair of hilltop camps situated above the storage galleries. These camps have yet to be excavated, but the researchers believe they were a control point where overseers monitored the harbor and could observe anyone approaching on desert trails. “Managing the site was an incredible logistical operation,” says Gregory Marouard, an archaeologist at Yale University who is part of Tallet’s team. “It took at least seven days to cross the desert from the Nile Valley, and they had to bring everything with them. There were also probably several different groups of workers involved, doing different jobs. And it was a seasonal operation, so when they organized a new expedition, people had to come to reopen the galleries, rebuild the boats, and so on.” Even before researchers uncovered the papyri detailing the activities of Merer and his men, many texts had already been found at Wadi el-Jarf. The ceramic storage jars, the large limestone blocks used to seal the storage galleries, and even the assemblage of stone anchors are all covered in hieroglyphs. The first thing the researchers noticed about these texts was the frequent presence of Khufu’s cartouche, an oval containing the pharaoh’s name, which helped establish that the site was used during his reign. As they looked further, they concluded that the texts consist of the names of work gangs that operated the harbor, such as “The Escort Team of ‘Great Is His Lion’” and “The Escort Team of ‘Khufu Confers on It His Two Uraei.’” “It took some time to understand what these names meant,” says Tallet. “But in the end, we figured out that these teams were probably named after the boats to which they were linked. And each boat was named from a royal insignia that it bore.” Thus, Inspector Merer’s “Escort Team of ‘The Uraeus of Khufu Is Its Prow,’” which was found written on hundreds of storage jars, apparently crewed a boat whose prow was decorated with the snake ornament worn by the king. The researchers would soon learn much more about these particular laborers.

Even before researchers uncovered the papyri detailing the activities of Merer and his men, many texts had already been found at Wadi el-Jarf. The ceramic storage jars, the large limestone blocks used to seal the storage galleries, and even the assemblage of stone anchors are all covered in hieroglyphs. The first thing the researchers noticed about these texts was the frequent presence of Khufu’s cartouche, an oval containing the pharaoh’s name, which helped establish that the site was used during his reign. As they looked further, they concluded that the texts consist of the names of work gangs that operated the harbor, such as “The Escort Team of ‘Great Is His Lion’” and “The Escort Team of ‘Khufu Confers on It His Two Uraei.’” “It took some time to understand what these names meant,” says Tallet. “But in the end, we figured out that these teams were probably named after the boats to which they were linked. And each boat was named from a royal insignia that it bore.” Thus, Inspector Merer’s “Escort Team of ‘The Uraeus of Khufu Is Its Prow,’” which was found written on hundreds of storage jars, apparently crewed a boat whose prow was decorated with the snake ornament worn by the king. The researchers would soon learn much more about these particular laborers.

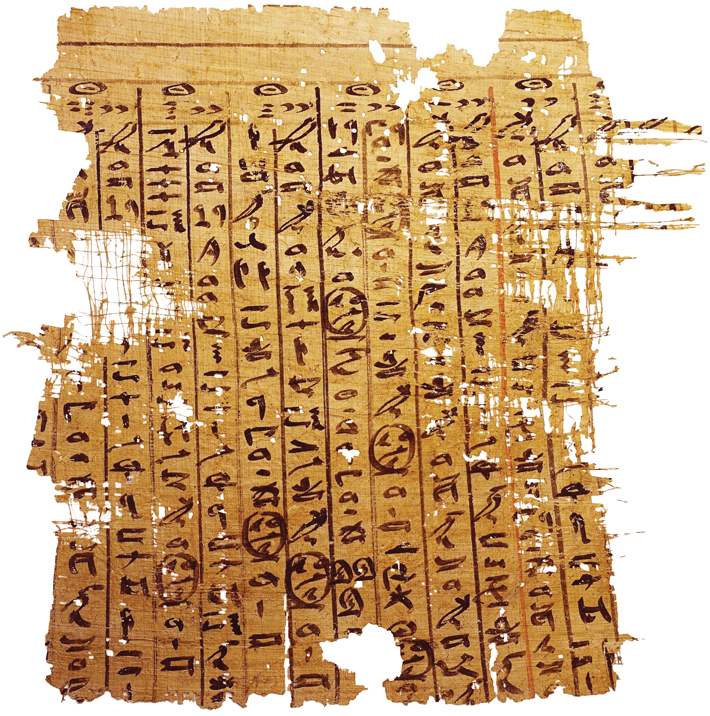

In the first few years of their excavations at Wadi el-Jarf, Tallet’s team unearthed a number of small blank or faded pieces of papyri, tantalizing hints that the site might hold inked papyri that had been waiting more than four and a half millennia to be found. In 2013, the researchers’ hopes were realized to a degree far greater than they could have imagined. While investigating the area in front of two storage galleries, they uncovered a few bits of papyri with red and black ink that proved to be scraps of accounting documents. Just under a week later, they excavated the first complete papyrus, which included one of Khufu’s royal names, Medjedu, or “the one who crushes.” This established it as the oldest inscribed papyrus ever found.

In the first few years of their excavations at Wadi el-Jarf, Tallet’s team unearthed a number of small blank or faded pieces of papyri, tantalizing hints that the site might hold inked papyri that had been waiting more than four and a half millennia to be found. In 2013, the researchers’ hopes were realized to a degree far greater than they could have imagined. While investigating the area in front of two storage galleries, they uncovered a few bits of papyri with red and black ink that proved to be scraps of accounting documents. Just under a week later, they excavated the first complete papyrus, which included one of Khufu’s royal names, Medjedu, or “the one who crushes.” This established it as the oldest inscribed papyrus ever found. With these waterways open, Merer’s men then spent several months hauling loads of fine limestone blocks from the Tura quarries to the Giza Plateau. A typical set of entries reads “Inspector Merer casts off with his phyle from Tura, loaded with stone, for Akhet Khufu; spends the night at She Khufu…. Sets sail from She Khufu, sails toward Akhet Khufu, loaded with stone; spends the night at Akhet Khufu.” The team picked the blocks up from two separate quarries—Tura North and Tura South—alternating every 10 days so quarry workers had time to extract stone and pile up blocks in anticipation of their next visit. These blocks were the sort used to encase the Great Pyramid, but this late in Khufu’s reign, it’s believed that this work would already have been completed. According to Egyptologist Mark Lehner, director of Ancient Egypt Research Associates, the blocks were most likely used as roofing for one of the pits near the pyramid that held cedar boats that would be used in Khufu’s funeral. “If it’s that close to the end of Khufu’s reign, maybe they were delivering the Tura limestone blocks for covering those boat pits, which are where they buried the funerary hearse boats,” he says. “I think that’s what makes the most sense.”

With these waterways open, Merer’s men then spent several months hauling loads of fine limestone blocks from the Tura quarries to the Giza Plateau. A typical set of entries reads “Inspector Merer casts off with his phyle from Tura, loaded with stone, for Akhet Khufu; spends the night at She Khufu…. Sets sail from She Khufu, sails toward Akhet Khufu, loaded with stone; spends the night at Akhet Khufu.” The team picked the blocks up from two separate quarries—Tura North and Tura South—alternating every 10 days so quarry workers had time to extract stone and pile up blocks in anticipation of their next visit. These blocks were the sort used to encase the Great Pyramid, but this late in Khufu’s reign, it’s believed that this work would already have been completed. According to Egyptologist Mark Lehner, director of Ancient Egypt Research Associates, the blocks were most likely used as roofing for one of the pits near the pyramid that held cedar boats that would be used in Khufu’s funeral. “If it’s that close to the end of Khufu’s reign, maybe they were delivering the Tura limestone blocks for covering those boat pits, which are where they buried the funerary hearse boats,” he says. “I think that’s what makes the most sense.” In December, when the Nile flood had ebbed and transporting heavy loads by boat to the Giza Plateau was no longer feasible, Merer’s phyle was sent to an area of the Nile Delta near a pair of towns. The names of these towns—Ro-Wer Idehu, or the Great River Mouth in the Marshes, and Ro-Maa, or the True River Mouth—likely refer to points where one or more of the Nile’s branches opened into the Mediterranean. There, the team was tasked with “tamping” or “compacting” a structure called a “double djadja,” which Tallet believes was likely a jetty of the sort uncovered at Wadi el-Jarf. Such a structure would have supported maritime expeditions to the Levant to obtain, among other materials, pine and cedar, which were generally unavailable in Egypt but were essential for making boats and stoking the fires used to process copper ore. “At that time in history, the Egyptians were trying to connect as much as they could with the outer world,” says Tallet. Ensuring the team did not go hungry or thirsty during this remote posting, the papyri note that an official named Imery made several trips to fetch rations of bread and beer.

In December, when the Nile flood had ebbed and transporting heavy loads by boat to the Giza Plateau was no longer feasible, Merer’s phyle was sent to an area of the Nile Delta near a pair of towns. The names of these towns—Ro-Wer Idehu, or the Great River Mouth in the Marshes, and Ro-Maa, or the True River Mouth—likely refer to points where one or more of the Nile’s branches opened into the Mediterranean. There, the team was tasked with “tamping” or “compacting” a structure called a “double djadja,” which Tallet believes was likely a jetty of the sort uncovered at Wadi el-Jarf. Such a structure would have supported maritime expeditions to the Levant to obtain, among other materials, pine and cedar, which were generally unavailable in Egypt but were essential for making boats and stoking the fires used to process copper ore. “At that time in history, the Egyptians were trying to connect as much as they could with the outer world,” says Tallet. Ensuring the team did not go hungry or thirsty during this remote posting, the papyri note that an official named Imery made several trips to fetch rations of bread and beer. Based on the contents of the papyri, Tallet believes that at least some workers in the time of Khufu were highly skilled and well rewarded for their labor, contradicting the popular notion that the Great Pyramid was built by masses of oppressed slaves. In several instances, Merer and his team were awarded gifts of textiles. In addition to a diet including poultry, fish, fruit, and a variety of breads, cakes, and beers, the men were also provided with dates and honey, delicacies that were extremely scarce and generally reserved for those within the royal entourage. In fact, the laborers may have been quite close to the royal family. During their several months working at the Giza Plateau, Inspector Merer’s phyle—and possibly other phyles that were part of the same group—appears to have taken turns guarding and helping to provision a royal institution called Ankhu Khufu, which likely referred to Khufu’s valley temple. In the papyri, Merer’s men are called the setep za, “the chosen phyle” or “the elite,” a phrase that can denote a royal guard force. “I think these boatmen were a very special category of workers because their activities were really vital for the royal project,” says Tallet. “I think the monarchy had an interest in being fair to them because it was essential to have them working well.”

Based on the contents of the papyri, Tallet believes that at least some workers in the time of Khufu were highly skilled and well rewarded for their labor, contradicting the popular notion that the Great Pyramid was built by masses of oppressed slaves. In several instances, Merer and his team were awarded gifts of textiles. In addition to a diet including poultry, fish, fruit, and a variety of breads, cakes, and beers, the men were also provided with dates and honey, delicacies that were extremely scarce and generally reserved for those within the royal entourage. In fact, the laborers may have been quite close to the royal family. During their several months working at the Giza Plateau, Inspector Merer’s phyle—and possibly other phyles that were part of the same group—appears to have taken turns guarding and helping to provision a royal institution called Ankhu Khufu, which likely referred to Khufu’s valley temple. In the papyri, Merer’s men are called the setep za, “the chosen phyle” or “the elite,” a phrase that can denote a royal guard force. “I think these boatmen were a very special category of workers because their activities were really vital for the royal project,” says Tallet. “I think the monarchy had an interest in being fair to them because it was essential to have them working well.”