Features

1,000 Fathoms Down

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, September 12, 2022

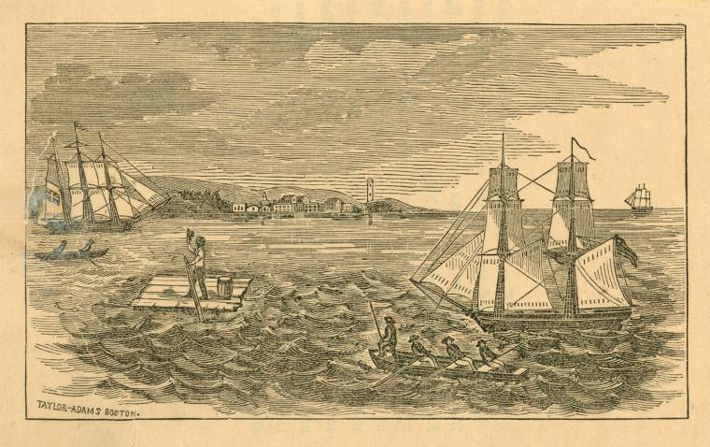

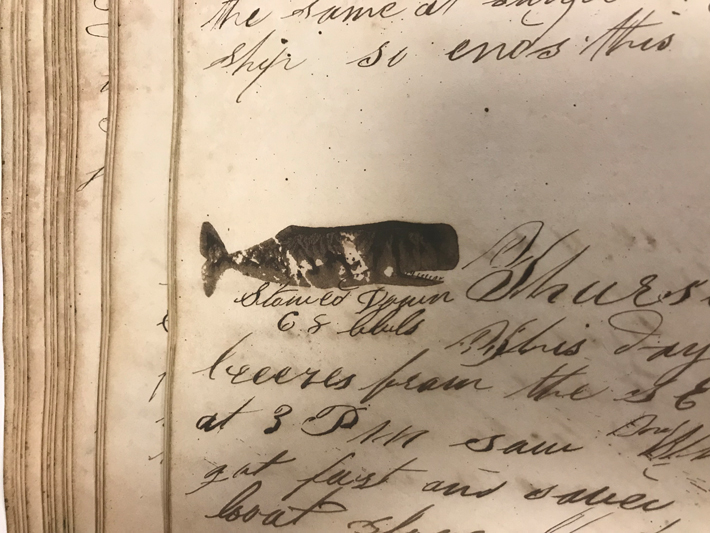

The first few weeks of May 1836 were pleasant ones for the whaling brig Industry. Based in Westport, Massachusetts, the two-masted, 64-foot-long ship had been built in 1815 and launched the next year. Now, two decades into her career, Industry and her crew of 15 men had been out for just over a year hunting sperm whales as far east as the Azores and as far south as the Caribbean. They had built up a store of several hundred barrels of sperm whale oil and were making their way back home when they detoured into the Gulf of Mexico in hopes of topping up their prized cargo.

The first few weeks of May 1836 were pleasant ones for the whaling brig Industry. Based in Westport, Massachusetts, the two-masted, 64-foot-long ship had been built in 1815 and launched the next year. Now, two decades into her career, Industry and her crew of 15 men had been out for just over a year hunting sperm whales as far east as the Azores and as far south as the Caribbean. They had built up a store of several hundred barrels of sperm whale oil and were making their way back home when they detoured into the Gulf of Mexico in hopes of topping up their prized cargo.

Before the widespread availability of petroleum, sperm whale oil was a valuable commodity. It burned clearly and brightly without smoking, making it ideal for illuminating homes and lighthouses. It was a fine lubricant even at very high temperatures, and was used to oil timepieces, scientific instruments, and industrial machinery. In addition, spermaceti, a waxy substance harvested from sperm whales’ heads, was used to produce the brightest, cleanest-burning candles. And ambergris, an odoriferous material found in some sperm whales’ bowels, was coveted as an ingredient in perfume and worth its weight in gold. “If you were good at killing whales, then you had the ability to make cash,” says Michael Dyer, curator of maritime history at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. “Anyone who participated in the whaling trade in the early nineteenth century could stand to do quite well at it.”

In the Gulf, Industry enjoyed a stretch of fine weather with steady winds and encountered a fellow Westport whaling brig, Elizabeth. The two ships “mated,” in the nautical parlance, and sailed in close proximity for several days. They were a few miles apart when a vicious squall set in on the evening of May 26. “The thunder rolled heavily and in the most terrific tones,” reports a June 20, 1836, article in the New-Bedford Gazette & Courier. “The lightnings flashed vividly and constantly in every direction during the night.”

In the Gulf, Industry enjoyed a stretch of fine weather with steady winds and encountered a fellow Westport whaling brig, Elizabeth. The two ships “mated,” in the nautical parlance, and sailed in close proximity for several days. They were a few miles apart when a vicious squall set in on the evening of May 26. “The thunder rolled heavily and in the most terrific tones,” reports a June 20, 1836, article in the New-Bedford Gazette & Courier. “The lightnings flashed vividly and constantly in every direction during the night.”

Industry got the worst of it. She was knocked on her side by the wind and waves, and nearly capsized. Both her masts snapped, and all but one of the small boats the crew used to pursue whales were washed away. The only thing keeping her afloat was the buoyancy provided by her precious store of sperm whale oil. The crew piled into their one remaining boat and rowed to Elizabeth, which took them in and sailed back to Westport. Around a week later, a Nantucket-based whaler named Harmony came upon the abandoned Industry and salvaged 230 of her 310 barrels of oil, along with valuable equipment including parts of her sails and rigging, her anchor cable, and at least one of her anchors. No longer buoyed by her full store of oil, Industry slipped under the water and began to drift to the seafloor. Of some 214 whaling ships known to have worked in the Gulf of Mexico between 1788 and 1878, Industry is the only one known to have sunk there.

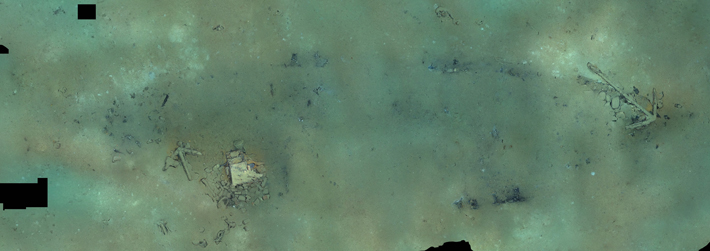

During a 2011 sonar survey of a stretch of the Gulf of Mexico slated for petroleum exploration, what appeared to be a shipwreck was detected around 70 miles from the mouth of the Mississippi River and reported to the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). Six years later, a test of an autonomous underwater vehicle captured images of the wreck, which lies 6,000 feet below the surface. The images showed features—in particular, what appeared to be a tryworks, or hearth used to render whale blubber into oil, and anchors of a style dating to the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century—that suggested the wreck might be that of a whaling vessel from the early nineteenth century. In February 2022, a team led by marine archaeologists James Delgado and Michael Brennan of the archaeological firm SEARCH and Scott Sorset of BOEM monitored footage from a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration remotely operated vehicle (ROV) as it spent several hours thoroughly documenting the wreck.

|

Sidebar:

|

A Maritime Magnate

|

|

Sidebar:

|

Passage to Freedom

|

Rediscovering Egypt's Golden Dynasty

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, August 22, 2022

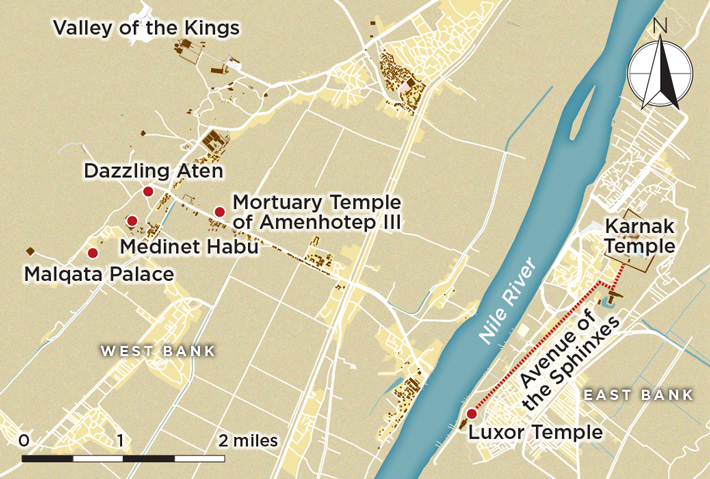

The banks of the Nile River in modern-day Luxor are strewn with so many ruins of Egypt’s illustrious past that the area is sometimes called the world’s largest open-air museum. Luxor was once ancient Thebes, the erstwhile capital of Egypt, and for more than 1,000 years, the pharaohs erected temples, monuments, and sculptures there as testaments to their power, wealth, and piety. The New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.), which many scholars believe was the cultural and artistic zenith of Egyptian civilization, was an especially prolific period. Among the archaeological sites on the Nile’s east bank are two of the largest and most important temples in all of Egypt, the Karnak Temple, called the “most selected of places” by ancient Egyptians, and the Luxor Temple, known to them as the “southern sanctuary.” These two massive religious complexes, both of which celebrated the holy Theban trinity of Amun-Ra, the greatest of gods, his consort Mut, and their son Khonsu, still boast reminders of their former glory—ornate columns, giant statues, soaring obelisks, and expertly carved reliefs. The complexes were connected by an almost two-mile-long grand processional way known as the Avenue of Sphinxes, lined with more than 600 ram-headed statues and sphinxes carved in stone.

The banks of the Nile River in modern-day Luxor are strewn with so many ruins of Egypt’s illustrious past that the area is sometimes called the world’s largest open-air museum. Luxor was once ancient Thebes, the erstwhile capital of Egypt, and for more than 1,000 years, the pharaohs erected temples, monuments, and sculptures there as testaments to their power, wealth, and piety. The New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1070 B.C.), which many scholars believe was the cultural and artistic zenith of Egyptian civilization, was an especially prolific period. Among the archaeological sites on the Nile’s east bank are two of the largest and most important temples in all of Egypt, the Karnak Temple, called the “most selected of places” by ancient Egyptians, and the Luxor Temple, known to them as the “southern sanctuary.” These two massive religious complexes, both of which celebrated the holy Theban trinity of Amun-Ra, the greatest of gods, his consort Mut, and their son Khonsu, still boast reminders of their former glory—ornate columns, giant statues, soaring obelisks, and expertly carved reliefs. The complexes were connected by an almost two-mile-long grand processional way known as the Avenue of Sphinxes, lined with more than 600 ram-headed statues and sphinxes carved in stone.

The most prominent archaeological remnants on the west bank, an area known to scholars as the “city of the dead,” are a group of mortuary temples built by some of the New Kingdom’s most notable rulers, including Hatshepsut (r. ca. 1479–1458 B.C.), Ramesses II (r. ca. 1279–1213 B.C.), and Ramesses III (r. ca. 1184–1153 B.C.). Mortuary or funerary temples were not where pharaohs were entombed, but where they were commemorated and worshipped for eternity after their deaths, alongside other Egyptian gods. Dwarfing all these complexes was the one known to have been built by Amenhotep III (r. ca. 1390–1352 B.C.).

The most prominent archaeological remnants on the west bank, an area known to scholars as the “city of the dead,” are a group of mortuary temples built by some of the New Kingdom’s most notable rulers, including Hatshepsut (r. ca. 1479–1458 B.C.), Ramesses II (r. ca. 1279–1213 B.C.), and Ramesses III (r. ca. 1184–1153 B.C.). Mortuary or funerary temples were not where pharaohs were entombed, but where they were commemorated and worshipped for eternity after their deaths, alongside other Egyptian gods. Dwarfing all these complexes was the one known to have been built by Amenhotep III (r. ca. 1390–1352 B.C.).

Amenhotep III presided over Egypt during an unprecedented time that is often referred to as the Egyptian Golden Age. The pharaoh initiated an extraordinary building campaign that spurred urban growth in his capital of Thebes. He commissioned monumental structures such as his mortuary temple, the scale of which is only just beginning to be understood as a result of archaeological research over the past two decades. The picture of Amenhotep III’s “golden” Thebes has only been enhanced by the recent chance discovery of a previously unknown city built during his reign, now buried amid the monuments of the west bank. Some archaeologists consider this city one of the most important discoveries of the past century in Egypt. The remnants of both the temple and the city now stand as potent reminders of an era of peace and prosperity that preceded one of the most tumultuous periods in Egyptian history.

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Digs & Discoveries

The Case of Tut's Missing Collar

Alpine Crystal Hunters

Don't Give an Inch

Australia's Blue Period

Romans Go Dutch

Surveying Samnium

Heart of the Matter

Mexican Star Power

Pictish Pictograms

Linking the Lineages

The Avars Advance

Herod's Fancy Fixtures

Off the Grid

Around the World

A pregnant tortoise, sunken Spanish cargo, Maya orthodontics, Mongol summer plans, and the first fruit farmers

Artifact

A memento left along the way

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

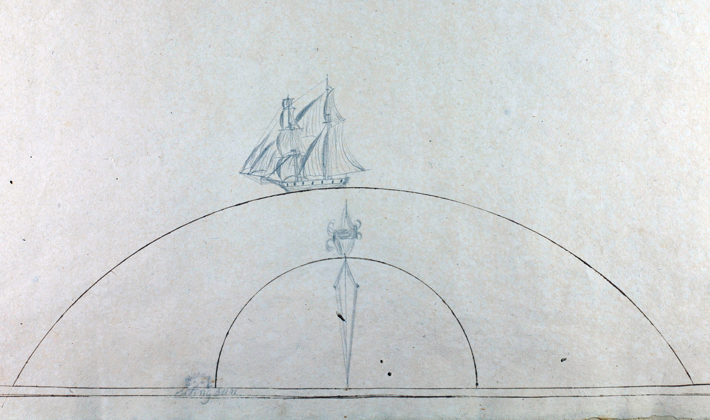

Images from the site collected by the ROV were used to create a 3-D model called an orthomosaic. Using this model, the researchers determined that the wreck’s length is 63 feet and its beam, or greatest width, is 20 feet. Both measurements are nearly identical to those of Industry as recorded in her original certificate of registration. Details of the ship’s structure that could be gleaned from the wreck site also meshed well with what is known of Industry: The wreck is a two-masted vessel with a shallow hull that lacked copper sheathing. The absence of sheathing meant that Industry’s hull was unprotected against the depredations of marine organisms, and the ship’s logbooks include references to her tendency to leak. The location of the wreck, too, some 83 miles north-northeast of Industry’s last known location, as recorded by the crew of Harmony, is consistent with the trajectory of a ship slowly sinking while caught in the Gulf of Mexico’s Loop Current. “We’ve gone back and looked at the data,” says Delgado, “and there are no other known wrecks within 100 miles that would fit.”

Images from the site collected by the ROV were used to create a 3-D model called an orthomosaic. Using this model, the researchers determined that the wreck’s length is 63 feet and its beam, or greatest width, is 20 feet. Both measurements are nearly identical to those of Industry as recorded in her original certificate of registration. Details of the ship’s structure that could be gleaned from the wreck site also meshed well with what is known of Industry: The wreck is a two-masted vessel with a shallow hull that lacked copper sheathing. The absence of sheathing meant that Industry’s hull was unprotected against the depredations of marine organisms, and the ship’s logbooks include references to her tendency to leak. The location of the wreck, too, some 83 miles north-northeast of Industry’s last known location, as recorded by the crew of Harmony, is consistent with the trajectory of a ship slowly sinking while caught in the Gulf of Mexico’s Loop Current. “We’ve gone back and looked at the data,” says Delgado, “and there are no other known wrecks within 100 miles that would fit.”

Rather than a typical tryworks, the researchers saw an iron stove known as a camboose resting atop a pile of bricks, a peculiar find for several reasons. First, shipboard cambooses known from the archaeological record typically sat on an insulating sheet of lead or iron, but no such metal sheet is evident at the wreck site. Second, unlike other known shipboard cambooses, which tend to have flat surfaces for heating cooking pots, the wreck’s camboose features two large open wells, both of which appear to be fitted with iron pots or cauldrons. For Delgado, this raises the possibility that the camboose was a hybrid tryworks, insulated by a brick hearth and used to render blubber into oil.

Rather than a typical tryworks, the researchers saw an iron stove known as a camboose resting atop a pile of bricks, a peculiar find for several reasons. First, shipboard cambooses known from the archaeological record typically sat on an insulating sheet of lead or iron, but no such metal sheet is evident at the wreck site. Second, unlike other known shipboard cambooses, which tend to have flat surfaces for heating cooking pots, the wreck’s camboose features two large open wells, both of which appear to be fitted with iron pots or cauldrons. For Delgado, this raises the possibility that the camboose was a hybrid tryworks, insulated by a brick hearth and used to render blubber into oil. Like other New England ports such as New Bedford, Nantucket, and New London, Westport grew wealthy from its involvement in the whaling industry. Unlike these other ports, however, which by the 1830s were home to larger whaleships that embarked on multiyear voyages to the Pacific or Indian Ocean, most of Westport’s fleet consisted of smaller ships such as Industry that went out for at most 14 months or so and usually stuck to the North Atlantic, Caribbean, and Gulf of Mexico. “Westport crews were, generally speaking, from the immediate community, and they all knew each other and were often related to each other,” says Dyer. For instance, according to Robin Winters of the Westport Free Public Library, Hiram Francis, who began Industry’s final voyage as captain, was a half brother of George Sowle, captain of Elizabeth, the ship that rescued Industry’s crew. There was also at least one pair of brothers aboard Industry when it got caught in the storm: David Sowle, who began the final voyage as first mate and appears to have taken over as captain along the way, and his younger brother Jethro.

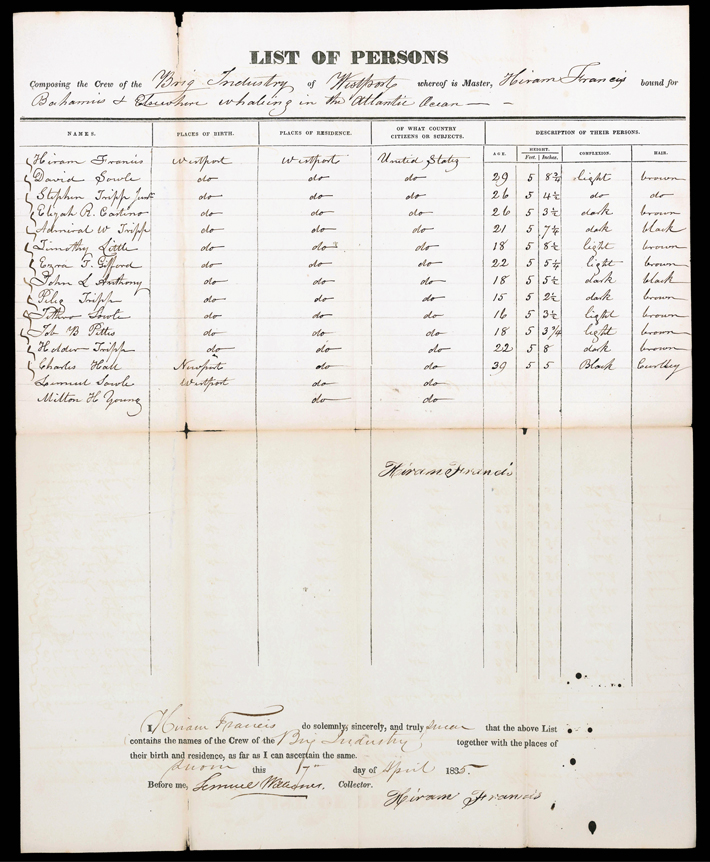

Like other New England ports such as New Bedford, Nantucket, and New London, Westport grew wealthy from its involvement in the whaling industry. Unlike these other ports, however, which by the 1830s were home to larger whaleships that embarked on multiyear voyages to the Pacific or Indian Ocean, most of Westport’s fleet consisted of smaller ships such as Industry that went out for at most 14 months or so and usually stuck to the North Atlantic, Caribbean, and Gulf of Mexico. “Westport crews were, generally speaking, from the immediate community, and they all knew each other and were often related to each other,” says Dyer. For instance, according to Robin Winters of the Westport Free Public Library, Hiram Francis, who began Industry’s final voyage as captain, was a half brother of George Sowle, captain of Elizabeth, the ship that rescued Industry’s crew. There was also at least one pair of brothers aboard Industry when it got caught in the storm: David Sowle, who began the final voyage as first mate and appears to have taken over as captain along the way, and his younger brother Jethro. Industry’s crew lists provide evidence that a significant portion of her crew over the course of her career was African American. While these lists don’t directly identify individuals’ race or ethnicity, they do specify their physical traits, describing their skin as “light,” “dark,” “mulatto,” “coloured,” “brown,” or “yellow” and their hair as “brown,” “black,” “wooly,” or “curley.” It appears that at least one crew member on Industry’s final voyage, named Charles Hall, was African American.

Industry’s crew lists provide evidence that a significant portion of her crew over the course of her career was African American. While these lists don’t directly identify individuals’ race or ethnicity, they do specify their physical traits, describing their skin as “light,” “dark,” “mulatto,” “coloured,” “brown,” or “yellow” and their hair as “brown,” “black,” “wooly,” or “curley.” It appears that at least one crew member on Industry’s final voyage, named Charles Hall, was African American. A century ago, in the autumn of 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter stunned the world with images of a tomb he had discovered in the Valley of the Kings on the Nile’s west bank. The photographs showed a small burial chamber filled with some 5,000 objects stacked nearly floor to ceiling, many of them made of gold. The tomb held the remains and funerary goods of Tutankhamun (r. ca. 1336–1327 B.C.), a relatively unheralded pharaoh who became Egypt’s ruler at the age of nine and reigned for only a decade.

A century ago, in the autumn of 1922, British archaeologist Howard Carter stunned the world with images of a tomb he had discovered in the Valley of the Kings on the Nile’s west bank. The photographs showed a small burial chamber filled with some 5,000 objects stacked nearly floor to ceiling, many of them made of gold. The tomb held the remains and funerary goods of Tutankhamun (r. ca. 1336–1327 B.C.), a relatively unheralded pharaoh who became Egypt’s ruler at the age of nine and reigned for only a decade. Archaeologists believed that, like several other 18th Dynasty (ca. 1550–1295 B.C.) pharaohs, Tutankhamun likely had a mortuary temple somewhere along the Nile’s west bank—but they had been unable to find it in such a vast area dotted with ruins. However, a clue to the temple’s location may have been buried with the pharaoh himself. Among the golden chairs, beds, and chariots was a relatively simple pottery vessel with an inscription suggesting that Tutankhamun’s temple was located near a place on the west bank known today as Medinet Habu. “The inscription indicated that the mortuary temple was built in the most sacred area of the god Amun, which is Medinet Habu,” says Egyptologist Zahi Hawass. “I thought further investigation was needed in this area.”

Archaeologists believed that, like several other 18th Dynasty (ca. 1550–1295 B.C.) pharaohs, Tutankhamun likely had a mortuary temple somewhere along the Nile’s west bank—but they had been unable to find it in such a vast area dotted with ruins. However, a clue to the temple’s location may have been buried with the pharaoh himself. Among the golden chairs, beds, and chariots was a relatively simple pottery vessel with an inscription suggesting that Tutankhamun’s temple was located near a place on the west bank known today as Medinet Habu. “The inscription indicated that the mortuary temple was built in the most sacred area of the god Amun, which is Medinet Habu,” says Egyptologist Zahi Hawass. “I thought further investigation was needed in this area.” Following this small but promising piece of evidence, in 2020 Hawass began his quest to find the temple just north of Medinet Habu, near the site of the mortuary temples of Ay (r. ca. 1327–1323 B.C.) and Horemheb (r. ca. 1323–1295 B.C.), two of Tutankhamun’s successors. As the excavations unfolded, Hawass’ team failed to turn up definitive evidence of Tutankhamun’s mortuary temple, but instead found something unexpected. As they began removing layers of debris amassed over thousands of years, they gradually exposed a network of well-preserved mudbrick walls that seemed to extend in every direction. Eventually they revealed streets, houses, storerooms, artists’ workshops, and industrial spaces, along with at least 1,000 artifacts. Some of the walls still stood to a height of 12 feet. Yet the settlement was an enigma as no ancient records mention it. Scholars wondered when it was founded, who built it, and what it was called. The answers became apparent when Hawass uncovered a series of wine jars. Mudbrick seals used to close the vessels were inscribed with hieroglyphs that spelled out the name of the city—Tehn Aten, or “Dazzling” Aten, a name that unequivocally pointed to one ruler: Tutankhamun’s grandfather, the pharaoh Amenhotep III. “I originally called it the Golden City or the Lost City because it dates to the reign of Amenhotep III, which was the Golden Age of ancient Egypt, and because nothing was known about it,” Hawass says.

Following this small but promising piece of evidence, in 2020 Hawass began his quest to find the temple just north of Medinet Habu, near the site of the mortuary temples of Ay (r. ca. 1327–1323 B.C.) and Horemheb (r. ca. 1323–1295 B.C.), two of Tutankhamun’s successors. As the excavations unfolded, Hawass’ team failed to turn up definitive evidence of Tutankhamun’s mortuary temple, but instead found something unexpected. As they began removing layers of debris amassed over thousands of years, they gradually exposed a network of well-preserved mudbrick walls that seemed to extend in every direction. Eventually they revealed streets, houses, storerooms, artists’ workshops, and industrial spaces, along with at least 1,000 artifacts. Some of the walls still stood to a height of 12 feet. Yet the settlement was an enigma as no ancient records mention it. Scholars wondered when it was founded, who built it, and what it was called. The answers became apparent when Hawass uncovered a series of wine jars. Mudbrick seals used to close the vessels were inscribed with hieroglyphs that spelled out the name of the city—Tehn Aten, or “Dazzling” Aten, a name that unequivocally pointed to one ruler: Tutankhamun’s grandfather, the pharaoh Amenhotep III. “I originally called it the Golden City or the Lost City because it dates to the reign of Amenhotep III, which was the Golden Age of ancient Egypt, and because nothing was known about it,” Hawass says. During the New Kingdom—with one brief interlude—Amun (or Amun-Ra), the supreme god, was worshipped as first among the Egyptian gods. Over time, however, Amenhotep III increasingly began to portray himself as a sun god and promoted a new aspect of the deity known as Aten to prominence. Aten was the disk of the sun, the giver of light and life, and Amenhotep III adopted the epithet “the dazzling Aten” for himself as well.

During the New Kingdom—with one brief interlude—Amun (or Amun-Ra), the supreme god, was worshipped as first among the Egyptian gods. Over time, however, Amenhotep III increasingly began to portray himself as a sun god and promoted a new aspect of the deity known as Aten to prominence. Aten was the disk of the sun, the giver of light and life, and Amenhotep III adopted the epithet “the dazzling Aten” for himself as well. Amenhotep III was the ninth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, one of ancient Egypt’s most storied bloodlines. Among its rulers were conquerors such as Ahmose (r. ca. 1550–1525 B.C.) and Thutmose III (r. ca. 1479–1425 B.C.), military commanders including Horemheb, the controversial king Akhenaten (r. ca. 1349–1336 B.C.), his renowned wife Nefertiti, and Tutankhamun, perhaps Egypt’s most famous ruler. The 18th Dynasty was the first dynasty of the New Kingdom and began when its founder, Ahmose, drove out the Hyksos, foreign kings who originally hailed from the Levant and who had ruled parts of northern Egypt for more than 200 years. Ahmose’s reunification of Egypt ushered in a period of unparalleled prosperity.

Amenhotep III was the ninth pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty, one of ancient Egypt’s most storied bloodlines. Among its rulers were conquerors such as Ahmose (r. ca. 1550–1525 B.C.) and Thutmose III (r. ca. 1479–1425 B.C.), military commanders including Horemheb, the controversial king Akhenaten (r. ca. 1349–1336 B.C.), his renowned wife Nefertiti, and Tutankhamun, perhaps Egypt’s most famous ruler. The 18th Dynasty was the first dynasty of the New Kingdom and began when its founder, Ahmose, drove out the Hyksos, foreign kings who originally hailed from the Levant and who had ruled parts of northern Egypt for more than 200 years. Ahmose’s reunification of Egypt ushered in a period of unparalleled prosperity. Although Amenhotep III, like other pharaohs, called his mortuary temple the House of Millions of Years, in actuality it only lasted for a century and a half. Around 1200 B.C., a devastating earthquake reduced it to ruins. Its stones, bricks, statues, and other materials were carted off to be reused in nearby construction projects and to adorn new temples, especially those of the pharaohs Ramesses II and Merneptah (r. ca. 1213–1203 B.C.). What was left was periodically flooded, until most of the sanctuary was covered in six to 10 feet of alluvial deposits. The greatest temple in ancient Egypt had all but disappeared.

Although Amenhotep III, like other pharaohs, called his mortuary temple the House of Millions of Years, in actuality it only lasted for a century and a half. Around 1200 B.C., a devastating earthquake reduced it to ruins. Its stones, bricks, statues, and other materials were carted off to be reused in nearby construction projects and to adorn new temples, especially those of the pharaohs Ramesses II and Merneptah (r. ca. 1213–1203 B.C.). What was left was periodically flooded, until most of the sanctuary was covered in six to 10 feet of alluvial deposits. The greatest temple in ancient Egypt had all but disappeared.

All that remained were the two gargantuan statues of Amenhotep III sitting at what had once been the temple’s main entrance. The northern statue was named Memnon by the Romans who associated it with the Ethiopian Trojan War hero-king Memnon, these behemoths each weigh more than 720 tons and rise to a height of nearly 70 feet. For more than 3,000 years, they towered above the Nile plain, but little else of the original structure was visible—that is, until the late 1990s, when Egyptologist Hourig Sourouzian began to lament the condition of the ruins and wonder what might still be buried beneath the surface. “The colossi were all you saw,” she says. “There were some column bases and fallen fragmented sculptures, but it looked like a field. I said, ‘I wish someone could do something to save this ruined temple.’” Sourouzian, with Rainer Stadelmann of the German Archaeological Institute and a few colleagues, made a proposal to the Egyptian authorities. They founded the Colossi of Memnon and Amenhotep III Temple Conservation Project, of which she is the current director. Over the past two and a half decades, her team has grown from a few scholars and a handful of workers to a total of more than 300. Their goal is to save the last remains of the temple from further degradation and to at least partially restore the parts that were felled by the earthquake or damaged by the passage of time.

All that remained were the two gargantuan statues of Amenhotep III sitting at what had once been the temple’s main entrance. The northern statue was named Memnon by the Romans who associated it with the Ethiopian Trojan War hero-king Memnon, these behemoths each weigh more than 720 tons and rise to a height of nearly 70 feet. For more than 3,000 years, they towered above the Nile plain, but little else of the original structure was visible—that is, until the late 1990s, when Egyptologist Hourig Sourouzian began to lament the condition of the ruins and wonder what might still be buried beneath the surface. “The colossi were all you saw,” she says. “There were some column bases and fallen fragmented sculptures, but it looked like a field. I said, ‘I wish someone could do something to save this ruined temple.’” Sourouzian, with Rainer Stadelmann of the German Archaeological Institute and a few colleagues, made a proposal to the Egyptian authorities. They founded the Colossi of Memnon and Amenhotep III Temple Conservation Project, of which she is the current director. Over the past two and a half decades, her team has grown from a few scholars and a handful of workers to a total of more than 300. Their goal is to save the last remains of the temple from further degradation and to at least partially restore the parts that were felled by the earthquake or damaged by the passage of time. To date, the team has reconstructed part of the peristyle court, which was once adorned with two huge stone stelas recording Amenhotep III’s accomplishments, as well as dozens of statues of the pharaoh and sculptures depicting sphinxes, a crocodile, a hippopotamus, falcon gods, and other deities. They have also discovered hundreds of statues of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet that once lined the court’s walls and passageways. Discovering such a great number of representations of the goddess is extraordinary, explains Sourouzian. “That our project would find so many was really a surprise,” she says. Scholars continue to question why effigies of the goddess were present in such great numbers in Amenhotep III’s temples; some suggest a plague may have ravaged Egypt at some point during his reign or perhaps Amenhotep III himself was ill and needed Sekhmet’s protection, Sourouzian says, because besides being a goddess who spreads illness, she also cures. Sourouzian believes that the abundance of statues may have also had to do with Sekhmet’s and Amenhotep III’s shared close connection with the sun. “After thirty years of reign, we know that this king celebrated his first jubilee, and later two more, and when he does that, he is assimilated to Ra and becomes a sun god,” she says. “Sekhmet is the manifestation of the daughter of Ra and she lights fires to annihilate the enemies of the sun. So Amenhotep surrounded himself with Sekhmets. You will find that the king made this monument to serve the gods, to be beneficial to them. The most important thing was to perform his piety.”

To date, the team has reconstructed part of the peristyle court, which was once adorned with two huge stone stelas recording Amenhotep III’s accomplishments, as well as dozens of statues of the pharaoh and sculptures depicting sphinxes, a crocodile, a hippopotamus, falcon gods, and other deities. They have also discovered hundreds of statues of the lion-headed goddess Sekhmet that once lined the court’s walls and passageways. Discovering such a great number of representations of the goddess is extraordinary, explains Sourouzian. “That our project would find so many was really a surprise,” she says. Scholars continue to question why effigies of the goddess were present in such great numbers in Amenhotep III’s temples; some suggest a plague may have ravaged Egypt at some point during his reign or perhaps Amenhotep III himself was ill and needed Sekhmet’s protection, Sourouzian says, because besides being a goddess who spreads illness, she also cures. Sourouzian believes that the abundance of statues may have also had to do with Sekhmet’s and Amenhotep III’s shared close connection with the sun. “After thirty years of reign, we know that this king celebrated his first jubilee, and later two more, and when he does that, he is assimilated to Ra and becomes a sun god,” she says. “Sekhmet is the manifestation of the daughter of Ra and she lights fires to annihilate the enemies of the sun. So Amenhotep surrounded himself with Sekhmets. You will find that the king made this monument to serve the gods, to be beneficial to them. The most important thing was to perform his piety.” One of the project’s most daunting endeavors has been to reerect the temple’s enormous statues. In a painstaking process, each of the hundreds of fragments of a given statue is cleaned, conserved, and joined to neighboring pieces. Then, these massive stone figures, each weighing hundreds of tons, must be carefully lifted and set back in their original positions. “It’s hard work,” says Sourouzian, “but we are constantly fascinated by this extraordinary heritage and we are strengthened every day by knowing we have saved these ruins from oblivion and destruction.”

One of the project’s most daunting endeavors has been to reerect the temple’s enormous statues. In a painstaking process, each of the hundreds of fragments of a given statue is cleaned, conserved, and joined to neighboring pieces. Then, these massive stone figures, each weighing hundreds of tons, must be carefully lifted and set back in their original positions. “It’s hard work,” says Sourouzian, “but we are constantly fascinated by this extraordinary heritage and we are strengthened every day by knowing we have saved these ruins from oblivion and destruction.” After decades of work, the splendor and grandeur of Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple can finally begin to be imagined. Sourouzian believes that there would not have been a great deal of open space within the enormous enclosure. Instead, it would have been filled with smaller temples, courtyards, processional ways, gardens, pools, storerooms, and priests’ quarters. Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple would have rivaled the great Karnak Temple across the river, but that complex was added to and built up over a period of 2,000 years until it eventually became the largest religious complex in the world, a distinction it retains. By contrast, Amenhotep III’s temple was completed during his 39-year reign. “Each Egyptian king liked to say they had done things that had never been seen before and that they surpassed all that was done in the past,” says Sourouzian. “But Amenhotep III really did surpass many things that were done before him. It’s a fantastic achievement which corresponds to the height of Egyptian civilization.”

After decades of work, the splendor and grandeur of Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple can finally begin to be imagined. Sourouzian believes that there would not have been a great deal of open space within the enormous enclosure. Instead, it would have been filled with smaller temples, courtyards, processional ways, gardens, pools, storerooms, and priests’ quarters. Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple would have rivaled the great Karnak Temple across the river, but that complex was added to and built up over a period of 2,000 years until it eventually became the largest religious complex in the world, a distinction it retains. By contrast, Amenhotep III’s temple was completed during his 39-year reign. “Each Egyptian king liked to say they had done things that had never been seen before and that they surpassed all that was done in the past,” says Sourouzian. “But Amenhotep III really did surpass many things that were done before him. It’s a fantastic achievement which corresponds to the height of Egyptian civilization.” Evidence of one way the pharaoh was able to accomplish this may lie just a few hundred yards away from his mortuary temple. The logistics of supplying and maintaining a complex of this size would have been extremely complicated and involved thousands of people. It would have required its own support city, one that, in fact, eventually rose just beyond its gates—the city of Dazzling Aten. Hawass’ ongoing excavations have thus far uncovered parts of three separate districts surrounded by serpentine walls. These districts were likely part of an even more extensive settlement—which may have reached the gates of Amenhotep III’s Malqata Palace to the southwest and Deir el-Medina to the north, where the workers who built the tombs in the Valley of the Kings lived. For Hawass, this new discovery dispels the misconception that, unlike other contemporaneous cultures, ancient Egypt lacked major metropolises. “It is the largest ancient Egyptian settlement ever found,” he says. “Egypt was not a civilization without cities.”

Evidence of one way the pharaoh was able to accomplish this may lie just a few hundred yards away from his mortuary temple. The logistics of supplying and maintaining a complex of this size would have been extremely complicated and involved thousands of people. It would have required its own support city, one that, in fact, eventually rose just beyond its gates—the city of Dazzling Aten. Hawass’ ongoing excavations have thus far uncovered parts of three separate districts surrounded by serpentine walls. These districts were likely part of an even more extensive settlement—which may have reached the gates of Amenhotep III’s Malqata Palace to the southwest and Deir el-Medina to the north, where the workers who built the tombs in the Valley of the Kings lived. For Hawass, this new discovery dispels the misconception that, unlike other contemporaneous cultures, ancient Egypt lacked major metropolises. “It is the largest ancient Egyptian settlement ever found,” he says. “Egypt was not a civilization without cities.” There is even evidence that sculptors working and living in Dazzling Aten created the hundreds of statues that once decorated the great peristyle court of Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple. “We have uncovered a workshop where the statues of Sekhmet were crafted,” Hawass says. “I believe they were all built in this city.” It’s also likely, he says, that some of the extra-ordinary objects that would be entombed with Tutankhamun just a few decades later were originally crafted by Dazzling Aten’s artisans. “It was the Golden Age of the New Kingdom,” says Hawass, “but if anyone closes their eyes to imagine the magnificence of this area with the palaces and the city of Dazzling Aten and the funerary temple, it goes beyond that, especially in the architecture and statuary.”

There is even evidence that sculptors working and living in Dazzling Aten created the hundreds of statues that once decorated the great peristyle court of Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple. “We have uncovered a workshop where the statues of Sekhmet were crafted,” Hawass says. “I believe they were all built in this city.” It’s also likely, he says, that some of the extra-ordinary objects that would be entombed with Tutankhamun just a few decades later were originally crafted by Dazzling Aten’s artisans. “It was the Golden Age of the New Kingdom,” says Hawass, “but if anyone closes their eyes to imagine the magnificence of this area with the palaces and the city of Dazzling Aten and the funerary temple, it goes beyond that, especially in the architecture and statuary.”