Tutankhamun Family

The Divine King and His Queen

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, August 22, 2022

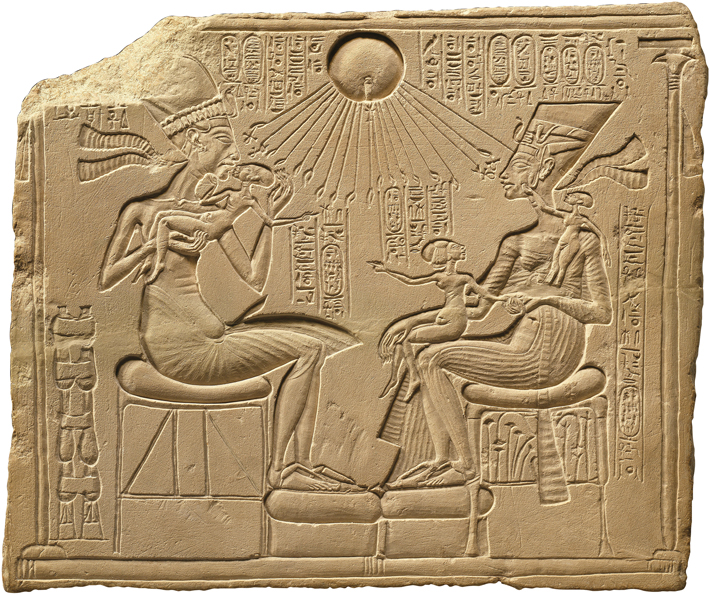

The 17-year reign of the pharaoh crowned as Amenhotep IV was one of the most revolutionary periods in Egyptian history. After the prosperous 39-year reign of his father, Amenhotep III, the pharaoh inherited a peaceful kingdom, which, says Egyptologist Arlette David of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, was a perfect setting for the blossoming of philosophical ideas—conditions the new pharaoh took full advantage of. Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaten five years into his reign to reflect his rejection of the main gods of the established pantheon and his promotion in their place of Aten, the god of light, as Egypt’s principal god. He also moved the royal capital 250 miles north from Thebes and built a city there that he called Akhetaten to rival his father’s Dazzling Aten. Several reliefs show Akhenaten and his Great Royal Wife, Nefertiti, with their daughters. But a newly studied relief from a monument at Karnak dating to around 1350 B.C.—just before Akhenaten turned the Egyptian world upside down—provides fascinating insight into the mind of the pharaoh.

The 17-year reign of the pharaoh crowned as Amenhotep IV was one of the most revolutionary periods in Egyptian history. After the prosperous 39-year reign of his father, Amenhotep III, the pharaoh inherited a peaceful kingdom, which, says Egyptologist Arlette David of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, was a perfect setting for the blossoming of philosophical ideas—conditions the new pharaoh took full advantage of. Amenhotep IV changed his name to Akhenaten five years into his reign to reflect his rejection of the main gods of the established pantheon and his promotion in their place of Aten, the god of light, as Egypt’s principal god. He also moved the royal capital 250 miles north from Thebes and built a city there that he called Akhetaten to rival his father’s Dazzling Aten. Several reliefs show Akhenaten and his Great Royal Wife, Nefertiti, with their daughters. But a newly studied relief from a monument at Karnak dating to around 1350 B.C.—just before Akhenaten turned the Egyptian world upside down—provides fascinating insight into the mind of the pharaoh.

The sandstone talatat, Akhenaten’s standardized building block, depicts the pharaoh and Nefertiti, assisted by male servants, preparing for their day. They are shown applying makeup, having their nails cut, purifying themselves, and dressing. “It looks like a very intimate household scene,” says David, but she believes that it actually shows them appropriating a well-known daily ritual described in later papyrus documents that was performed for the cult statue in the most sacred chamber of the temple of the creator god Amun-Ra at Karnak. Through the imagery on the relief, explains David, the pharaoh proclaims himself the divine personification of his personal god, Aten. “Akhenaten didn’t build everything from scratch,” she says. “His decision to throw away the Theban gods was extreme and shocking, but he used already-existing rituals, images, and texts, and recycled them to adapt to his new vision of kingship in which he was the center of everything and alone under his god.”

Who Was Tut’s Mother?

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, August 22, 2022

Perhaps one of the most surprising mysteries still surrounding the family of King Tutankhamun is the identity of his mother. She is never mentioned in an inscription and, even though the pharaoh’s tomb is filled with thousands upon thousands of personal objects, not a single artifact states her name. Two female mummies found in 1898 in a side chamber of the Valley of the Kings’ tomb of Amenhotep II, referred to as the “Elder Lady” and the “Younger Lady,” provide some tentative answers.

Perhaps one of the most surprising mysteries still surrounding the family of King Tutankhamun is the identity of his mother. She is never mentioned in an inscription and, even though the pharaoh’s tomb is filled with thousands upon thousands of personal objects, not a single artifact states her name. Two female mummies found in 1898 in a side chamber of the Valley of the Kings’ tomb of Amenhotep II, referred to as the “Elder Lady” and the “Younger Lady,” provide some tentative answers.

At some point, these two mummies, along with those of nine kings, including Tut’s grandfather Amenhotep III, had been moved to the tomb. By comparing DNA taken from the Elder Lady’s mummy with that from a lock of brown hair found in a miniature coffin inscribed with the name Tiye—Tut’s grandmother, the wife of Amenhotep III—inside Tut’s tomb, Egyptologist Zahi Hawass was able to identify the Elder Lady as Tiye. Tutankhamun, whose mother died when he was very young, is thought to have been particularly close to Tiye, so perhaps the lock of hair served as a memento.

The Younger Lady’s mummy is badly damaged. According to Hawass, she was 5 feet 1 inch tall, and lived to between 25 and 35. CT scans of the mummy performed by radiologists Sahar Saleem and Ashraf Selim of Cairo University suggest she had a serious injury on the left side of her face that was most likely inflicted before mummification. As Hawass explains, the subcutaneous embalming packs and filling were not disturbed, and the fractured fragments of her left jawbone were missing. “This may denote that the broken bone fragments were removed by the embalmers, who also partly cleaned the region of the injury,” says Hawass.

Although the Younger Lady is not named, she is thought to be Tut’s mother, a daughter of Amenhotep III and Tiye, and wife to her brother Akhenaten, Tut’s father. “We know that it is unlikely that either of Akhenaten’s known wives, Nefertiti or Kiya, was Tutankhamun’s mother, as there is no evidence from the sources that either was Akhenaten’s sister,” says Hawass. (Tut’s mother is known to have been one of Akhenaten’s sisters.) “Just which of his many sisters the Younger Lady is may never be known—he seems to have had almost forty sisters.”

The Pharaoh’s Daughters

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, August 22, 2022

For three years after his 1922 discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, archaeologist Howard Carter did not think much about an undecorated wooden box that turned out to contain two small resin-covered coffins, each of which held a smaller gold-foil-covered coffin. Inside these coffins were two tiny mummies. Preoccupied, Carter numbered the box 317 and did little to study it or its contents, only unwrapping the smaller of the two mummies, which he called 317a. The larger mummy he called 317b. The mummies were not carefully examined until 1932, when they were autopsied and photographed, at which time they were identified as stillborn female fetuses. But the most recent work on these two tiny girls, undertaken by radiologist Sahar Saleem of Cairo University, tells more of their story.

For three years after his 1922 discovery of King Tutankhamun’s tomb, archaeologist Howard Carter did not think much about an undecorated wooden box that turned out to contain two small resin-covered coffins, each of which held a smaller gold-foil-covered coffin. Inside these coffins were two tiny mummies. Preoccupied, Carter numbered the box 317 and did little to study it or its contents, only unwrapping the smaller of the two mummies, which he called 317a. The larger mummy he called 317b. The mummies were not carefully examined until 1932, when they were autopsied and photographed, at which time they were identified as stillborn female fetuses. But the most recent work on these two tiny girls, undertaken by radiologist Sahar Saleem of Cairo University, tells more of their story.

A decade ago, as head radiologist of the Egyptian Mummy Project, Saleem CT scanned the two fetuses, the first time any mummified fetus was studied using this technology. Though there is no evidence of the babies’ personal names—they are identified only by gold bands on the coffins calling them Osiris, the Egyptian god of the dead—they were, in fact, the daughters of Tutankhamun and his wife, Ankhesenamun, and were buried alongside their father after his death. Although both mummies were badly damaged, Saleem found that the girls died at 24 and 36 weeks’ gestation. It was previously known that the older girl, 317b, had had her organs removed as was typical to prepare the deceased for mummification. Saleem found an incision used to remove the organs on the side of 317a, as well as packing material of the sort placed under the skin of royal mummies to make them appear more lifelike. This contradicted the long-held belief that, unlike her sister, the younger girl had not been deliberately mummified.

Similarly, by scanning the mummies, Saleem was able to definitively disprove previous claims that the girls had suffered from congenital abnormalities such as spina bifida. “They got it wrong,” she says. “The damage to their skeletons is a result of postmortem fractures and poor storage. For example, 317b’s elongated head is not a result of cranial abnormalities as has previously been said, but because she has a broken skull.” For Saleem, though, what she has learned about Tutankhamun’s daughters goes beyond these scientific questions. “I try to feel the person as a human in their journey of life,” she says. “Regardless of their age at death, Tut’s daughters were seen as worthy of receiving the most expert mummifications, of a royal burial with their father, and of an afterlife.”

Tut the Antiquarian

By DANIEL WEISS

Monday, August 22, 2022

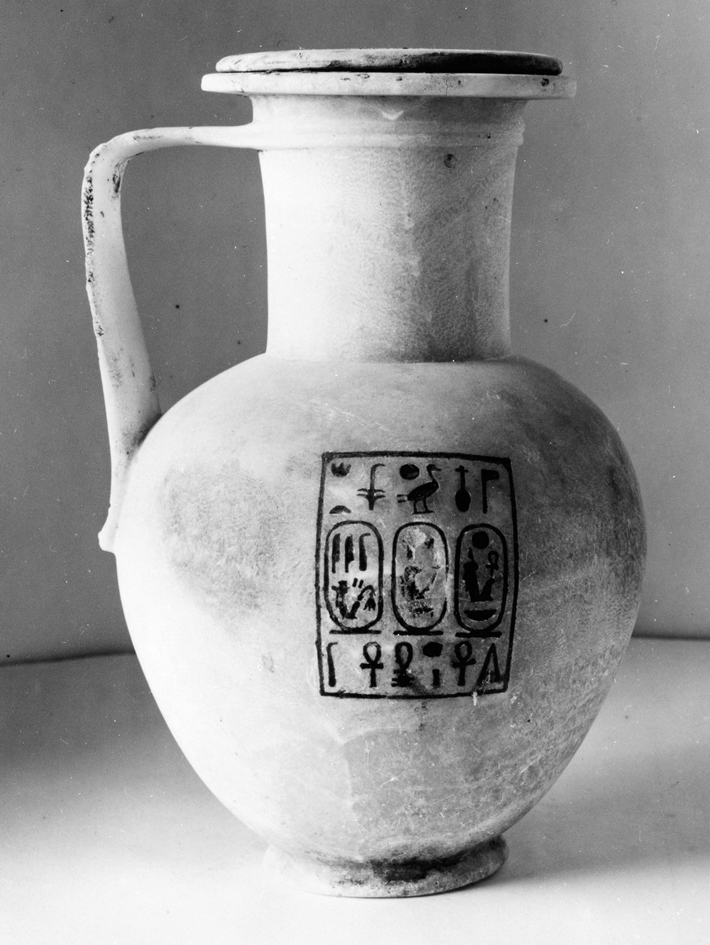

In the century since archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb and revealed its magnificent contents to the world, scholars and enthusiasts alike have been fascinated by the insights they provide into the life of a powerful Egyptian ruler more than three millennia ago. By studying some of the more unassuming items in the tomb’s inventory—a set of 11 alabaster vessels—Egyptologist Martin Bommas of Macquarie University has found evidence that Tutankhamun himself also took a keen interest in his country’s past. Bommas says these vessels were originally used by some of Tutankhamun’s illustrious predecessors, whose names are inscribed on them: the pharaoh Thutmose III, who reigned more than a century before Tutankhamun, as well as the boy king’s grandparents Amenhotep III and Tiye.

In the century since archaeologist Howard Carter discovered the pharaoh Tutankhamun’s tomb and revealed its magnificent contents to the world, scholars and enthusiasts alike have been fascinated by the insights they provide into the life of a powerful Egyptian ruler more than three millennia ago. By studying some of the more unassuming items in the tomb’s inventory—a set of 11 alabaster vessels—Egyptologist Martin Bommas of Macquarie University has found evidence that Tutankhamun himself also took a keen interest in his country’s past. Bommas says these vessels were originally used by some of Tutankhamun’s illustrious predecessors, whose names are inscribed on them: the pharaoh Thutmose III, who reigned more than a century before Tutankhamun, as well as the boy king’s grandparents Amenhotep III and Tiye.

The vessels held emulsions, creams, and oils, residues of which were still present when Carter opened the tomb in 1922. “These were not artifacts that you put on your mantelpiece, they were in daily use,” says Bommas. “The interesting thing is they were restored over a period of time, perhaps even in Tutankhamun’s lifetime.” Given that such vessels could have been made quite cheaply, the question is why Tutankhamun didn’t request new pots inscribed with his own name. Bommas believes the young pharaoh opted to use these antiquated objects as a way of surrounding himself with the aura of history. “At some point, as part of his education, Tutankhamun would have asked, ‘Who were my forefathers? Who was my granddad?’” says Bommas. “And they would have looked through the palaces and collected the vessels and said something like, ‘This is the pot that Thutmose III used after his Euphrates campaign.’ This would have been a wonderful way for Tutankhamun to link with his past.”

In particular, Bommas suggests, the vessels may have been a way for Tutankhamun to reconnect with traditions that held sway before his father, the pharaoh Akhenaten, shifted Egypt’s religious focus from the creator god Amun-Ra to the god of light, Aten. As Tutankhamun made clear in the so-called Restoration Stela, found in the Karnak Temple, Akhenaten’s religious experiment had been a disaster for the country. “The temple and cities of the gods and goddesses…were fallen into decay and their shrines were fallen into ruin, having become mere mounds overgrown with grass,” he writes. According to Bommas, “The problem for Tutankhamun was to reconnect with the time before Atenism. There was no other way for him but to study history, and these vessels informed him about the importance of the Egyptian past.”

Who Came Next?

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Monday, August 22, 2022

When the pharaoh Akhenaten died, he left no obvious successor. Three of his and his wife Nefertiti’s six daughters had died, and his son, Tutankhaten (later Tutankhamun) was too young to be king. Who would rule Egypt and bring peace back to a land rent by the religious revolution led by Akhenaten? For present-day scholars, too, the answer is far less than evident. The chronology of deaths and inheritors to the throne, which is usually relatively clear in Egyptian history, is extremely murky during this period.

When the pharaoh Akhenaten died, he left no obvious successor. Three of his and his wife Nefertiti’s six daughters had died, and his son, Tutankhaten (later Tutankhamun) was too young to be king. Who would rule Egypt and bring peace back to a land rent by the religious revolution led by Akhenaten? For present-day scholars, too, the answer is far less than evident. The chronology of deaths and inheritors to the throne, which is usually relatively clear in Egyptian history, is extremely murky during this period.

Some have suggested that Akhenaten’s successor was Nefertiti herself. But a particularly interesting alternate theory has recently been advanced by Egyptologist Marc Gabolde of Paul-Valéry Montpellier 3 University. “We are sure that a queen-pharaoh ruled between Akhenaten and Tutankhamun,” he says. “The clues I have gathered allow us to say that it was not Nefertiti, who died a few months before her husband. The ruler is therefore Meritaten.” Meritaten was one of Akhenaten and Nefertiti’s surviving daughters, and Tutankhamun’s older sister. (Other chronologies state that Nefertiti died after Akhenaten.)

Three of the Amarna Letters—a collection of hundreds of cuneiform tablets discovered in Akhenaten’s capital city of Akhetaten in the late nineteenth century—mention Meritaten using the name Mayati. In two of these letters, she is said to have quasi-royal status, Gabolde explains. After Nefertiti’s death, however, Meritaten appears without her previous title of royal daughter, but as “first lady” and later with a nearly royal rank. “This can only be properly explained if she is now becoming queen-pharaoh,” Gabolde says. Furthermore, at least one artifact from Tutankhamun’s tomb, which originally belonged to the queen-pharaoh, has two cartouches side by side, one with her coronation name, Ankhkheperure, and the other her birth name, Meritaten. “This ensures that the queen-pharaoh is none other than Meritaten,” says Gabolde.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement