Passage to Freedom

September/October 2022

In the popular understanding, the Underground Railroad consisted largely of people making their way north over land. In fact, says Michael Dyer, curator of maritime history at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, many, if not most, enslaved people who escaped to freedom did so by boat. “The coastal commerce of the East Coast of the United States before the Civil War was like standing on an interstate overpass and watching the tractor-trailers go by,” Dyer says. “It was constant, with sloops and schooners going up and back all the time. So the potential for enslaved individuals to make their way north on shipboard was high.” Moreover, many enslaved people worked on the waterfront, providing skills and connections that aided in their escape.

In the popular understanding, the Underground Railroad consisted largely of people making their way north over land. In fact, says Michael Dyer, curator of maritime history at the New Bedford Whaling Museum, many, if not most, enslaved people who escaped to freedom did so by boat. “The coastal commerce of the East Coast of the United States before the Civil War was like standing on an interstate overpass and watching the tractor-trailers go by,” Dyer says. “It was constant, with sloops and schooners going up and back all the time. So the potential for enslaved individuals to make their way north on shipboard was high.” Moreover, many enslaved people worked on the waterfront, providing skills and connections that aided in their escape.

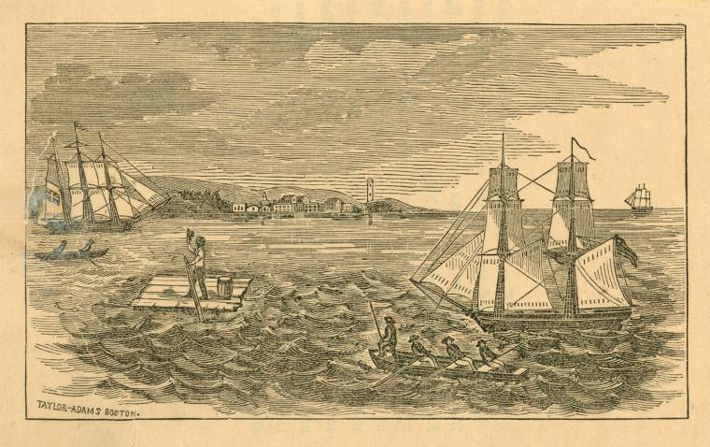

Some people seeking freedom stowed away with full complicity of the crew, as in the case of William Grimes, who fled in 1814 from Savannah, Georgia, to New York on the sloop Casket. The Boston-based crew took a liking to Grimes, who helped load the ship, and they left a space amid the cargo of cotton bales lashed on deck where he could hide during the voyage. Other fugitives, such as Thomas H. Jones, occupied a more precarious position onboard. In 1849, Jones bribed a steward on the cargo brig Bell bound for New York from Wilmington, North Carolina, to hide him in the hold, but was discovered by the captain en route. Fearing he’d be sent back into slavery, Jones jumped ship in New York Harbor, paddled toward shore on a makeshift raft, and was rescued by sympathetic boaters.

Southern authorities attempted to prevent maritime escapes by passing laws requiring a thorough search of all northbound ships and by fumigating them with a foul mixture of pitch, tar, vinegar, and sulfur. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, which forbade aiding and abetting people fleeing enslavement, put a legal onus on captains and crew. While they often obeyed the letter of the law, they frequently did little to help return fugitives to captivity. Newspapers in northern ports developed a standardized text that ship captains could publish as legal notice when they delivered a fugitive to free soil. For example, in the April 20, 1797, edition of The Medley or Newbedford Marine Journal, William Taber, captain of the sloop Union, posted an advertisement stating that he had discovered a stowaway “who had concealed himself unbeknown to me” after leaving Virginia for New Bedford. “It appearing inconsistent for me to return, the wind being ahead, I proceeded on my voyage and landed him in this Port,” Taber writes. “He calls himself JAMES, is about 27 years old, and says he belongs to Mr. Shacleford, a Planter, in Kings and Queen’s County, Virginia. Any person claiming him, will know by this information where he is.” As these papers tended to be weeklies, escapees were afforded time to move on before anyone could apprehend them.

Once escaped slaves were in the North, signing onto a whaling expedition was an appealing option for some who wanted to be certain they weren’t caught and re-enslaved. “If a man made it to New Bedford or wherever, he could sign onboard a whaler because they didn’t care who you were,” says Dyer. “As long as you didn’t have tuberculosis and weren’t a drunkard, they’d hire you. And once you joined a whaler, you were out of sight, out of mind, for years. Nobody is going to be able to track you down if you’re someplace in the Indian Ocean or the North Pacific.”

|

Article:

|

1,000 Fathoms Down

|