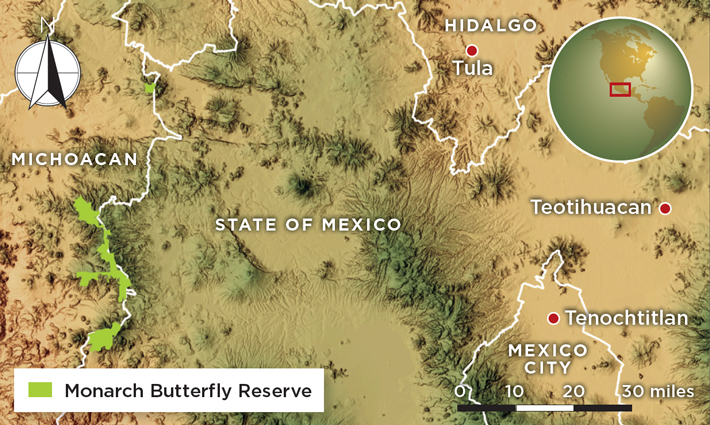

Overnight temperatures in the fir forests of central Mexico hover just above freezing in January. It’s the ideal temperature for the enormous colonies of monarch butterflies that, in late August, begin their 3,000-mile migration south to this small mountainous region. They overwinter until March, when they begin the journey back to the north. This sliver of fir forest, first discovered by biologists in 1975, has a microclimate that draws the monarchs that spend their summer months in the vast swath of Canada and the United States east of the Rocky Mountains. Scientists estimate that by October, when all the butterflies have arrived, each acre occupied by a colony can hold up to 25 million monarchs. It’s thought that, even though monarch butterfly populations have dropped 84 percent in just the last two decades, more than a billion of the colorful insects still find their way home to a protected reserve in the mountains of Michoacan State and Mexico State every year.

For nearly two millennia, butterflies have been vital to the belief systems of the Indigenous people of central Mexico. The Aztecs, also called the Mexica, viewed butterflies as the embodiment of the souls of warriors slain in battle. Archaeologists have discovered evidence of the widespread prevalence of butterfly symbols at such cities as Teotihuacan, which flourished from 100 B.C. to A.D. 650, and Tula, the capital of the Toltec people from about A.D. 850 to 1150. University of Copenhagen Mesoamericanist Jesper Nielsen is exploring the possibility that the tradition of depicting butterflies that began at Teotihuacan is linked to the symbolic significance ancient people may have attached to the annual monarch migration.

In pre-Columbian times, this migration involved even more butterflies than the mind-boggling one billion that fly to central Mexico today, and the insects may have once overwintered much closer to cities such as Teotihuacan and the Mexica capital of Tenochtitlan in forests that no longer exist. “Observing so many monarch butterflies every year at the same time may have been the basis for the idea of the return of dead warriors to the world of the living,” says Nielsen. “The monarchs arrive from the north, and in many traditions in central Mexico, that cardinal direction is associated with death.” It’s possible that the ritual commemorations of the dead that the Mexica held in the fall, and that endure in the form of Mexico’s Day of the Dead holiday, can be traced to the monarch butterflies’ yearly journey.

Nielsen notes that anyone experiencing the monarch migration in person will have their imagination fired by the sight of millions of butterflies perched on every available fir branch. “When I first visited a butterfly preserve, I thought, ‘OK, they are insects.’ I was ready to simply observe them.” But after walking along a narrow forest path and reaching a colony, he couldn’t help but be deeply moved. “Seeing that many living beings at one time, and such beautiful ones, it affects you,” Nielsen says. “We have to be careful and remember that we aren’t ancient Mesoamericans and can’t see things as they did. But if one did believe that butterflies could be linked to dead souls, to all those who came before us—this huge anonymous family that we ourselves will someday be part of—the experience would be overwhelming.”

Observing the transformation of a butterfly egg to larva to chrysalis to winged insect has struck a chord for many cultures, and butterflies have been seen as a symbol of rebirth and eternal life by people living all over the world for millennia. In Hindu tradition, the butterfly is often considered a powerful symbol of reincarnation, the ancient Greeks associated the concept of a soul with butterflies, and in medieval Europe, butterfly imagery was often associated with Jesus Christ.

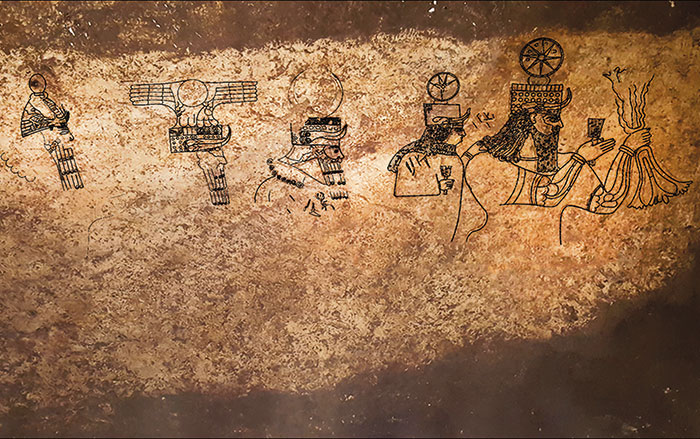

In Mexico, the connection between warriors and butterflies was noted by the sixteenth-century Spanish priest Bernardino de Sahagún. He recorded that the Mexica believed that dead warriors spent four years in the realm of the sun god Tonatiuh before returning to Earth as butterflies or hummingbirds, who would then suck nectar from flowers as their reward. In de Sahagún’s account, which he illustrated with drawings made by his Mexica students, warriors are depicted wearing back racks, a type of ceremonial gear, in the shape of butterflies.

At Teotihuacan, artists depicted butterflies on both murals and ceramics. One vessel excavated at the city is decorated with a swarm of butterflies in flight that could be intended to depict a monarch migration. The most finely wrought images of butterflies, though, are found on ornate ceramic incensarios, or incense burners. Teotihuacan incensarios are elaborate sculptures that resemble small theaters, with a human face at the center surrounded by a frame decorated with fired clay objects, primarily weapons such as darts and shields, and also animals and plants. Many incensarios depict men accompanied by stylized butterflies. In the late 1990s, a team led by Arizona State University archaeologist Saburo Sugiyama discovered an incensario workshop in a ritual complex at Teotihuacan near a structure known as the Pyramid of the Feathered Serpent. The pyramid is the site of a mass burial of what are presumed to be both warriors from Teotihuacan and those they took captive. Sugiyama suggests that there was an official cult in the city that celebrated dead warriors, and that incensarios were made under the supervision of powerful members of society in order to celebrate individual warriors. “If that’s correct,” says Nielsen, “then the sheer number of incensarios with butterfly imagery suggests that butterflies played an important role in this cult.”

Archaeologists believe that Teotihuacan was the birthplace of fundamental ideas that have persisted to the present day. The Toltec people, who first appeared 200 years after the fall of Teotihuacan, borrowed many motifs and symbols from the ancient city. At the main pyramid in the Toltec capital of Tula, for instance, stand four 15-foot-tall statues depicting warriors. Each of these statues wears a stylized butterfly as a breastplate, suggesting that the link between warriors and butterflies continued among the Toltec.

Recently, it has also become clear that butterfly iconography abounds in some of the city-states that became prominent in the immediate aftermath of the fall of Teotihuacan and before the rise of Tula. This suggests that the people of central Mexico maintained an uninterrupted ritual focus on butterflies and warriors from the earliest days of Teotihuacan to the founding of Tenochtitlan almost 1,500 years later. “It’s an unbroken continuity,” says Nielsen.

Butterflies loomed large in the Mesoamerican imagination, but no direct evidence yet exists that the event of the monarch migration itself was significant to ancient central Mexicans. No known ritual structures, such as temple platforms, have been found near the present-day overwintering grounds of the butterflies, making it difficult to know if people from Teotihuacan or later cultures ventured into the mountains to observe the monarch colonies as they hibernated. And butterflies on Teotihuacan incensarios and Toltec warrior sculptures are highly stylized, making it nearly impossible to determine which species they are meant to depict. “We don’t have firm evidence that suggests the migration played an important role in these cultures, but we do know that these people were very aware of what was going on in the landscape around them,” says Nielsen. “Swarms of millions of butterflies arriving at a particular time of the year from the direction associated with the region of death had to be meaningful for them.” Nielsen notes that when the Spanish arrived, they observed that the Mexica calendar set aside two months in the fall as a time to celebrate the ancestors. “We should be aware that there was this outstanding natural phenomenon that took place every year close to cultures that put an emphasis on butterflies as a symbol of death and rebirth,” says Nielsen. “The migration could have been an important natural event.”

After the Spanish conquest, the idea of a link between the souls of the dead and butterflies in Indigenous cultures of central Mexico faded. But in the past decade, monarch butterfly imagery has resurfaced in celebrations of the Day of the Dead. Participants in Day of the Dead parades have begun to dress as monarchs, and decorations bearing butterfly motifs have taken their place alongside more traditional imagery celebrating the holiday. Nielsen notes that the publication of a popular children’s book, I Remember Abuelito, in 2007, in which a girl imagines her dead grandfather as a migrating monarch butterfly, may be partly responsible for the resurgence in monarch imagery. The butterfly’s vivid orange and black coloring may also play a role, as elements of Halloween continue to be adopted in Mexico and incorporated into Day of the Dead celebrations. Perhaps, suggests Nielsen, this new emphasis on the monarch butterfly is an echo of a far older tradition, one that imagined the dead flying home, returning year after year to a place of safety and shelter in the mountain forests of central Mexico.