Top 10

Inside a Pharaoh's Coffin

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Tuesday, December 06, 2022

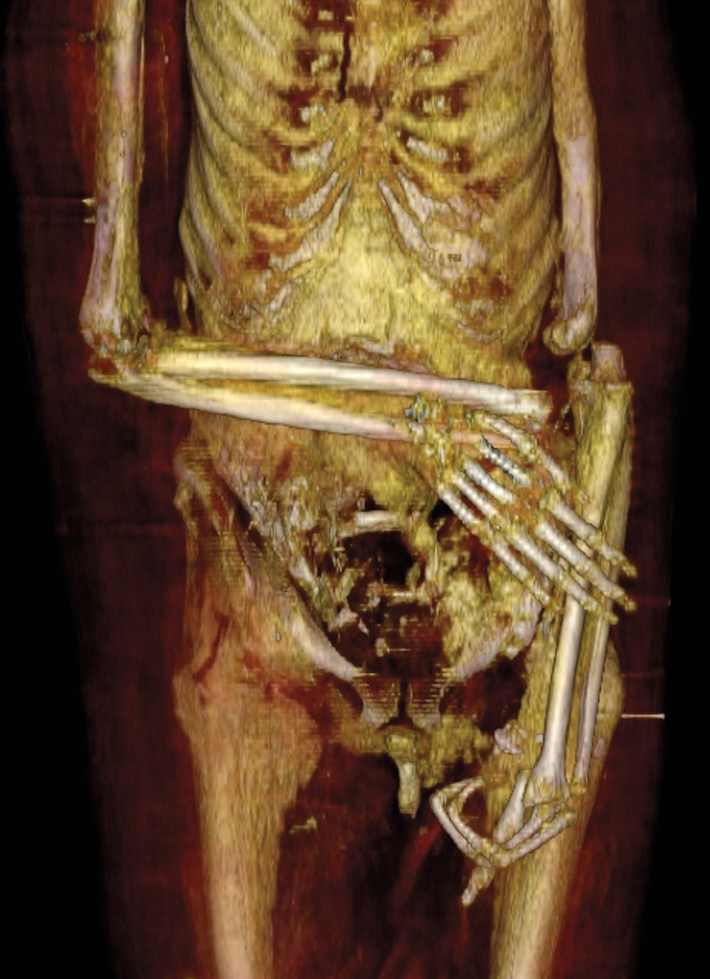

It’s not every day that scientists have the opportunity to look inside the coffin of a member of ancient Egyptian royalty—and to do so without opening it might seem impossible. But the sarcophagus containing the pharaoh Amenhotep I (reigned ca. 1525–1504 B.C.) has now been virtually opened and the mummy inside virtually unwrapped, revealing a wealth of new information about one of Egypt’s great rulers. Amenhotep I’s mummy, which was found in 1881, is one of very few known royal mummies that have not been unwrapped in modern times. During the Victorian era, wealthy patrons threw many exclusive mummy unwrapping parties. “The mummy was never unwrapped because scholars at the time thought it was too beautiful to destroy,” says radiologist Sahar Saleem of Cairo University, who led the project. Using noninvasive CT scanning, Saleem has generated 3-D images of the pharaoh’s mask, bandages, body, and face. “To see the pharaoh’s face after 3,000 years and how much he resembled his father, Ahmose, was very moving,” she says.

It’s not every day that scientists have the opportunity to look inside the coffin of a member of ancient Egyptian royalty—and to do so without opening it might seem impossible. But the sarcophagus containing the pharaoh Amenhotep I (reigned ca. 1525–1504 B.C.) has now been virtually opened and the mummy inside virtually unwrapped, revealing a wealth of new information about one of Egypt’s great rulers. Amenhotep I’s mummy, which was found in 1881, is one of very few known royal mummies that have not been unwrapped in modern times. During the Victorian era, wealthy patrons threw many exclusive mummy unwrapping parties. “The mummy was never unwrapped because scholars at the time thought it was too beautiful to destroy,” says radiologist Sahar Saleem of Cairo University, who led the project. Using noninvasive CT scanning, Saleem has generated 3-D images of the pharaoh’s mask, bandages, body, and face. “To see the pharaoh’s face after 3,000 years and how much he resembled his father, Ahmose, was very moving,” she says.

Amenhotep I’s mummy was not found in its original burial location but in the ancient town of Deir el-Bahari, where it was part of a cache of mummies, many of them royal as well. These mummies had been collected during the 21st Dynasty (ca. 1070–945 B.C.) by priests who rewrapped and reinterred them in new coffins. Many of the cache’s mummies had been badly damaged by tomb robbers before being collected. Saleem’s scans show that the priests who rewrapped and reinterred Amenhotep I’s mummy carefully reattached his head with a resin-treated linen band. His neck had been broken, likely when looters tore off a necklace. They also rearranged his broken left arm, covered a hole in his stomach, and placed gold amulets inside. “The study provides evidence for the great care taken by the priests of the 21st Dynasty in reburying the mummy of Amenhotep I, preserving the golden ornaments, and placing many amulets inside,” Saleem says. “This restores confidence in the goodwill of the priests to rebury the royal mummies to preserve them, contrary to modern allegations that the goal was to steal the ornaments.” She was also able to see that the pharaoh’s right arm had been folded over his chest in its original mummification position. “Folding the arms on the chest became characteristic of royal mummies to make them resemble Osiris, god of the afterlife,” Saleem says. “Amenhotep I’s mummy is the first example of this style of mummification, which later became standard for all ancient Egyptian mummies.”

Amenhotep I’s mummy was not found in its original burial location but in the ancient town of Deir el-Bahari, where it was part of a cache of mummies, many of them royal as well. These mummies had been collected during the 21st Dynasty (ca. 1070–945 B.C.) by priests who rewrapped and reinterred them in new coffins. Many of the cache’s mummies had been badly damaged by tomb robbers before being collected. Saleem’s scans show that the priests who rewrapped and reinterred Amenhotep I’s mummy carefully reattached his head with a resin-treated linen band. His neck had been broken, likely when looters tore off a necklace. They also rearranged his broken left arm, covered a hole in his stomach, and placed gold amulets inside. “The study provides evidence for the great care taken by the priests of the 21st Dynasty in reburying the mummy of Amenhotep I, preserving the golden ornaments, and placing many amulets inside,” Saleem says. “This restores confidence in the goodwill of the priests to rebury the royal mummies to preserve them, contrary to modern allegations that the goal was to steal the ornaments.” She was also able to see that the pharaoh’s right arm had been folded over his chest in its original mummification position. “Folding the arms on the chest became characteristic of royal mummies to make them resemble Osiris, god of the afterlife,” Saleem says. “Amenhotep I’s mummy is the first example of this style of mummification, which later became standard for all ancient Egyptian mummies.”

Aztec Offerings

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Tuesday, December 06, 2022

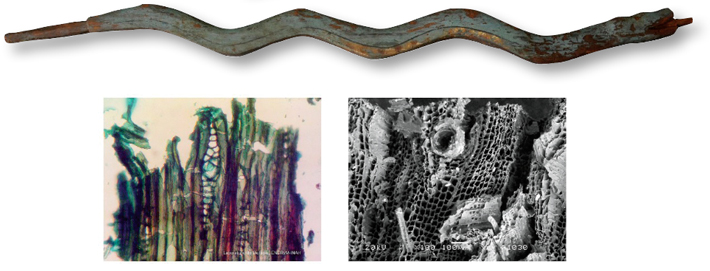

Innovative preservation techniques and advanced microscopy are revealing new insights into the creation and symbolic significance of a remarkably well-preserved collection of 2,550 wooden artifacts unearthed by a team of archaeologists led by Leonardo López Luján at the foot of the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Aztecs, or Mexica. The finely carved objects, which include scepters, ear flares, nose and finger rings, and miniature masks and weapons, were buried between 1486 and 1502 as ritual offerings. All the items are associated with deities the Mexica venerated in the temple—the god of war, Huitzilopochtli, and the rain god, Tlaloc. Priests deposited the wood items in stone boxes that also contained marine shells, plants, and animal and human bones. “Most of the offerings were waterlogged or had a very high level of humidity,” says Templo Mayor Project conservator Adriana Sanromán. “This preserved the wooden objects, but has also caused them to deteriorate.” While the waterlogged conditions helped to preserve the wood and traces of painted decoration on many of the items, chemical processes have weakened the wood structures, leading to cracks and other deformations over the centuries since the offerings were buried.

Innovative preservation techniques and advanced microscopy are revealing new insights into the creation and symbolic significance of a remarkably well-preserved collection of 2,550 wooden artifacts unearthed by a team of archaeologists led by Leonardo López Luján at the foot of the Templo Mayor in Tenochtitlan, the capital city of the Aztecs, or Mexica. The finely carved objects, which include scepters, ear flares, nose and finger rings, and miniature masks and weapons, were buried between 1486 and 1502 as ritual offerings. All the items are associated with deities the Mexica venerated in the temple—the god of war, Huitzilopochtli, and the rain god, Tlaloc. Priests deposited the wood items in stone boxes that also contained marine shells, plants, and animal and human bones. “Most of the offerings were waterlogged or had a very high level of humidity,” says Templo Mayor Project conservator Adriana Sanromán. “This preserved the wooden objects, but has also caused them to deteriorate.” While the waterlogged conditions helped to preserve the wood and traces of painted decoration on many of the items, chemical processes have weakened the wood structures, leading to cracks and other deformations over the centuries since the offerings were buried.

In the course of their ongoing efforts to stabilize the artifacts and prevent further damage, Sanromán and her colleague María Barajas submerge them in increasing concentrations of a synthetic sugar mixture, which displaces the water in the wood’s cell structure. They then dry the artifacts and remove any excess sugar. This complex, multistage conservation process can take up to a year. By scrutinizing tiny wood samples under a scanning electron microscope, the researchers have identified different species of wood Mexica artisans used to create the offerings. Most of the objects sampled were carved from pine harvested in the forests of central Mexico, while others were fashioned from mesquite, fir, cypress, alder, or butterfly bush. “All of these are soft woods that made it easy to carve these very detailed miniature objects,” Barajas says. Although sculptors’ choice of specific wood types may have depended in part on availability, their selections seem to have held religious significance as well. “We think that certain species of wood were chosen for both their physical qualities and their symbolic meaning,” says Templo Mayor Project archaeologist Víctor Cortés. “For example, Huitzilopochtli was associated with mesquite, and Tlaloc with pine.”

In the course of their ongoing efforts to stabilize the artifacts and prevent further damage, Sanromán and her colleague María Barajas submerge them in increasing concentrations of a synthetic sugar mixture, which displaces the water in the wood’s cell structure. They then dry the artifacts and remove any excess sugar. This complex, multistage conservation process can take up to a year. By scrutinizing tiny wood samples under a scanning electron microscope, the researchers have identified different species of wood Mexica artisans used to create the offerings. Most of the objects sampled were carved from pine harvested in the forests of central Mexico, while others were fashioned from mesquite, fir, cypress, alder, or butterfly bush. “All of these are soft woods that made it easy to carve these very detailed miniature objects,” Barajas says. Although sculptors’ choice of specific wood types may have depended in part on availability, their selections seem to have held religious significance as well. “We think that certain species of wood were chosen for both their physical qualities and their symbolic meaning,” says Templo Mayor Project archaeologist Víctor Cortés. “For example, Huitzilopochtli was associated with mesquite, and Tlaloc with pine.”

World's Oldest Straws

By DANIEL WEISS

Tuesday, December 06, 2022

A novel interpretation of eight gold and silver tubes discovered in southern Russia dating to around 3500 B.C. suggests that they may be the world’s oldest drinking straws. The tubes were found alongside one of three skeletons in a burial mound known as the Maikop kurgan, which was excavated in 1897. The richly furnished mound also contained hundreds of other artifacts, including ceramic vessels, metal cups, weapons, and beads made of semiprecious stones and gold. The tubes, which are hollow and measure around 3.7 feet long and just under a half inch in diameter, were originally thought to have been scepters or poles used to support a canopy.

A novel interpretation of eight gold and silver tubes discovered in southern Russia dating to around 3500 B.C. suggests that they may be the world’s oldest drinking straws. The tubes were found alongside one of three skeletons in a burial mound known as the Maikop kurgan, which was excavated in 1897. The richly furnished mound also contained hundreds of other artifacts, including ceramic vessels, metal cups, weapons, and beads made of semiprecious stones and gold. The tubes, which are hollow and measure around 3.7 feet long and just under a half inch in diameter, were originally thought to have been scepters or poles used to support a canopy.

Viktor Trifonov, an archaeologist at the Russian Academy of Sciences’ Institute for the History of Material Culture, suspected the tubes might have had a very different purpose. He thought they may have been used as straws in a communal drinking activity of a sort depicted in Mesopotamian artwork discovered in present-day Iraq dating to the fourth millennium B.C. To test his hypothesis, he focused his investigation on the tubes’ silver tips, which are perforated in a manner that might help filter a beverage’s impurities. Trifonov analyzed the residue from one of these tips and revealed the presence of barley starch granules, fossilized particles of plant tissue, and a pollen grain from a lime tree, possible evidence that the tubes were used to imbibe barley beer. He believes the practice of sipping a libation with one’s compatriots in this manner likely originated in Mesopotamia and then spread to the area around Maikop.

The Birth of Venus

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Tuesday, December 06, 2022

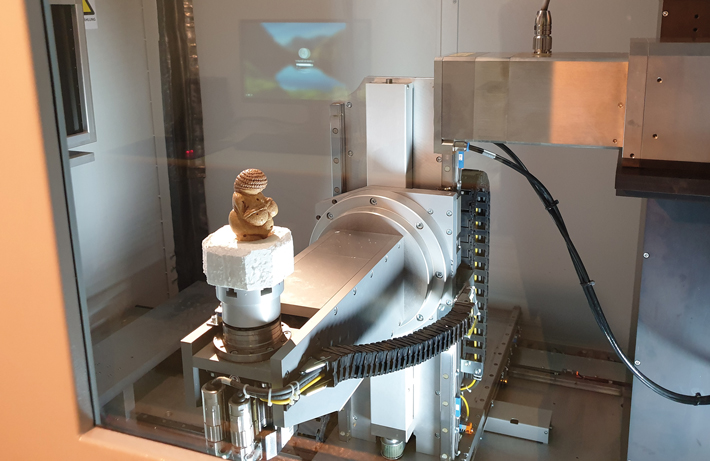

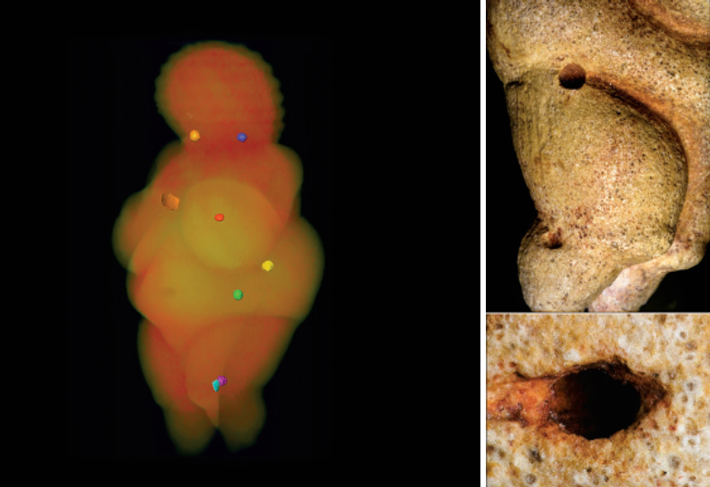

For more than a century since the 30,000-year-old stone sculpture known as the Venus of Willendorf was found on the banks of the Danube River in its eponymous village, many unknowns have swirled around the 4.3-inch-tall figurine. But the lingering mystery of where the material used to make the sculpture originated has now been solved, opening new avenues of research into how far people of the Gravettian period (ca. 30,000–22,000 years ago) traveled. Using a technique called high-resolution micro-computed tomography, a team led by Gerhard Weber of the University of Vienna scanned the figurine. Several other figurines with which it was found were made of ivory, but the Venus was fashioned from oolitic limestone, a type of sedimentary rock whose composition varies greatly by location. “Oolite acts like a kind of geological fingerprint,” Weber says. The team expected to find that the stone had been sourced within 100 miles of Willendorf. Instead, to their surprise, they discovered that it had come from some 450 miles away, near Sega di Ala in the Italian Alps. The researchers believe the figurine was likely carved there before being carried across the mountains. “While this journey could have taken years, decades, or centuries,” says Weber, “finding a way through the Alps might not have been as big a barrier in the Ice Age as we always imagine.”

For more than a century since the 30,000-year-old stone sculpture known as the Venus of Willendorf was found on the banks of the Danube River in its eponymous village, many unknowns have swirled around the 4.3-inch-tall figurine. But the lingering mystery of where the material used to make the sculpture originated has now been solved, opening new avenues of research into how far people of the Gravettian period (ca. 30,000–22,000 years ago) traveled. Using a technique called high-resolution micro-computed tomography, a team led by Gerhard Weber of the University of Vienna scanned the figurine. Several other figurines with which it was found were made of ivory, but the Venus was fashioned from oolitic limestone, a type of sedimentary rock whose composition varies greatly by location. “Oolite acts like a kind of geological fingerprint,” Weber says. The team expected to find that the stone had been sourced within 100 miles of Willendorf. Instead, to their surprise, they discovered that it had come from some 450 miles away, near Sega di Ala in the Italian Alps. The researchers believe the figurine was likely carved there before being carried across the mountains. “While this journey could have taken years, decades, or centuries,” says Weber, “finding a way through the Alps might not have been as big a barrier in the Ice Age as we always imagine.”

The high-resolution scans also allowed researchers to see details of structural components of the sculpture that have always been puzzling. They now know that hemispherical cavities on the surface of the limestone were once filled by limonites, or iron oxide concretions, that likely fell out during the carving process because they are harder than the limestone. One of these cavities is in the center of the figurine’s stomach where the navel should be. “There are some traces, such as furrows from a tool, that suggest this limonite could have been removed intentionally, which would mean the artist already had a very precise idea of the later shape of the figurine,” says Weber. “That would tell us a lot about these Paleolithic people’s thinking.”

The high-resolution scans also allowed researchers to see details of structural components of the sculpture that have always been puzzling. They now know that hemispherical cavities on the surface of the limestone were once filled by limonites, or iron oxide concretions, that likely fell out during the carving process because they are harder than the limestone. One of these cavities is in the center of the figurine’s stomach where the navel should be. “There are some traces, such as furrows from a tool, that suggest this limonite could have been removed intentionally, which would mean the artist already had a very precise idea of the later shape of the figurine,” says Weber. “That would tell us a lot about these Paleolithic people’s thinking.”

Neolithic Hunting Shrine

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, December 06, 2022

In the deserts of southeastern Jordan around 9,000 years ago, hunters erected a stone shrine that is one of the earliest ritual structures ever unearthed. A team led by archaeologists Mohammad Tarawneh of Al-Hussein Bin Talal University and Wael Abu-Azizeh of the French Institute of the Near East discovered the shrine in a Neolithic campsite near a network of “desert kites.” Desert kites consist of pairs of rock walls that extend across the landscape, often over several miles, and converge on an enclosure where prey such as gazelles could be herded and then easily dispatched. The team previously established that the kites near the shrine date to the Neolithic period (12,000 to 7,000 years ago in Jordan) and have now discovered clear evidence of the shrine’s connection to these enormous hunting installations.

In the deserts of southeastern Jordan around 9,000 years ago, hunters erected a stone shrine that is one of the earliest ritual structures ever unearthed. A team led by archaeologists Mohammad Tarawneh of Al-Hussein Bin Talal University and Wael Abu-Azizeh of the French Institute of the Near East discovered the shrine in a Neolithic campsite near a network of “desert kites.” Desert kites consist of pairs of rock walls that extend across the landscape, often over several miles, and converge on an enclosure where prey such as gazelles could be herded and then easily dispatched. The team previously established that the kites near the shrine date to the Neolithic period (12,000 to 7,000 years ago in Jordan) and have now discovered clear evidence of the shrine’s connection to these enormous hunting installations.

The shrine was built as a scale model of a kite, and one of two standing stelas found in the structure bears a stylized depiction of a desert kite. The team also unearthed a large stone altar with a number of incisions near a hearth. “One hypothesis is that the stone altar was used for butchering gazelle carcasses in the context of ritual activities carried out within the shrine,” says Abu-Azizeh. “The ritual performance most likely invoked supernatural forces for successful hunts.” A surprising cache of some 150 marine fossils was also found in the shrine, but the collection’s purpose remains unknown.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement