In 1715, a Mandinga man from the Gambia region of West Africa who would go down in history under the name Francisco Menéndez escaped from enslavement in the English colony of South Carolina to join up with local Native Americans, the Yamasee, who were waging war against his former captors. Menéndez fought alongside the Yamasee for a few months. At times, the Yamasee came close to driving the English out of the Carolinas, but superior colonial reinforcements eventually arrived. Later in 1715, Menéndez and several other formerly enslaved people, likely including his Mandinga wife, guided by their Yamasee comrades, traveled south toward St. Augustine, the capital of the Spanish colony of Florida. They had heard that the Spanish king had promised freedom to people fleeing slavery—provided they converted to Catholicism.

Enslaved people seeking liberty had sought refuge in St. Augustine since at least 1687, when eight men, two women, and a young child arrived by boat from the Carolinas. An edict issued by Spain’s King Charles II (reigned 1665–1700) in 1693 giving “liberty to all” formalized the Spanish policy of welcoming formerly enslaved people, and their numbers increased as word of the proclamation spread. Menéndez’s journey to freedom, however, was interrupted when a Yamasee man known as Perro Bravo, or Mad Dog, claimed ownership of him and several others who had fought against the English in the Carolinas. The acting governor of Florida purchased the hostages, and Menéndez was later sold at auction to the royal accountant, Francisco Menéndez Márquez, whose name he adopted at his Catholic baptism. The royal accountant became Menéndez’s godparent and entrusted him with a great deal of responsibility. Still, Menéndez filed multiple petitions with Spanish authorities protesting his continued enslavement, to no avail. “Even though he’s in a very important household, that of one of the most important officers in St. Augustine, Menéndez is still not free like he is supposed to be,” says historian Jane Landers of Vanderbilt University.

Relations between the Spanish and English colonies were always tense and often erupted into armed conflict. By offering escaped slaves their freedom, the Spanish struck an economic blow against the English, depriving them of a valuable labor force. They took advantage of the new arrivals’ hatred of their former English enslavers to strike a military blow as well. “Who would be more resistant to the British than those who had been enslaved by them?” asks Landers. In 1726, Florida Governor Antonio de Benavides appointed Menéndez commander of a newly formed militia composed of formerly enslaved people. This fighting force played a key role in defending St. Augustine against an English invasion in 1728.

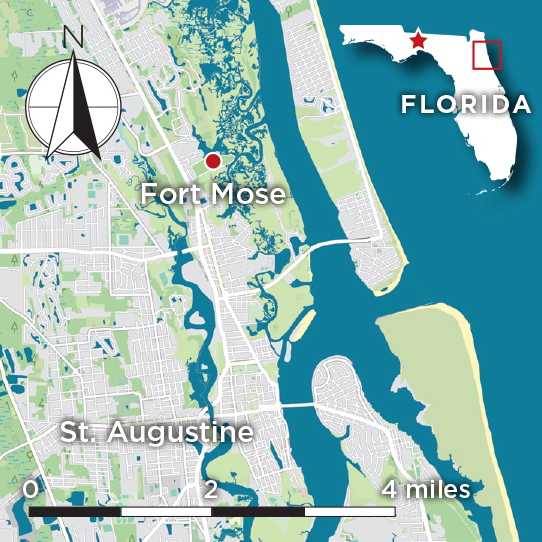

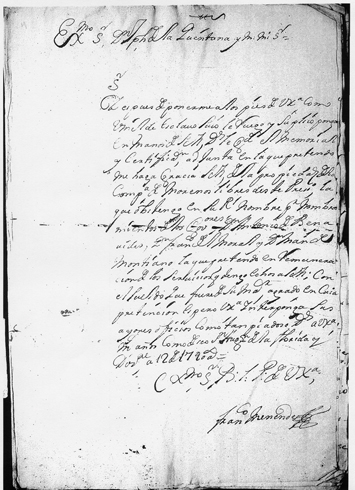

More than 100 escapees had made their way from the English colonies to St. Augustine by 1738. That year, a new Florida governor, Manuel de Montiano, reviewed Menéndez’s latest petition, which included testimony from a Yamasee leader regarding his bravery in the fight against the English in South Carolina and blaming his continued enslavement on the “infidel” Mad Dog. Montiano granted unconditional freedom to Menéndez and other escapees who had been re-enslaved in Florida. The governor also moved Menéndez’s militia to a newly established town two miles north of St. Augustine that he named Gracia Real de Santa Teresa de Mose, known today as Fort Mose. There, the militia would serve as the northernmost defenders of the Spanish colonial capital against British attacks.

The initial settlement at Fort Mose was decidedly small-scale. The walls of the square fort were made of earth and logs and measured just 70 feet or so on a side. The fort was surrounded by a moat and contained a lookout tower and a fortified house. In historical terms, however, Fort Mose looms large. It was the first legally sanctioned free Black town in the lands that would become the United States and thus holds great resonance for the area’s Black community today. “This was the first underground railroad,” says Landers. “And it went south, not to Canada.”

Over the past half century, a number of archaeologists have explored the site of Fort Mose, which now lies within Fort Mose Historic State Park, in an effort to learn more about the settlement, which included not just the Black militia members, but also their families and a series of friars installed by the Spanish authorities to attend to their spiritual development. In the 1980s, a team led by archaeologist Kathleen Deagan of the Florida Museum of Natural History, informed by Landers’ documentary research, discovered remnants of a second iteration of Fort Mose. More recently, archaeologists Lori Lee of Flagler College, Liz Ibarrola of the University of Texas at Austin, and James Davidson of the University of Florida have returned to the site for further excavation. Alongside them, Chuck Meide of the Lighthouse Archaeological Maritime Program is leading underwater excavations in sections of the fort that are now submerged, as well as in a creek that flowed by it. “We’re particularly interested in the domestic side of things,” says Ibarrola. “What did the conversion to Catholicism look like? What did people’s daily life look like and how did it change when they moved to this place?” The new finds are showing how Menéndez, his fellow militiamen, and their families survived on the frontier of the Spanish Empire.

The Fort Mose militia took its role as defenders of the colony extremely seriously. In a declaration to the king of Spain, its members pledged to be “the most cruel enemies of the English” and to put their lives on the line and spill their “last drop of blood in defense of the Great Crown of Spain and the Holy Faith.” They wouldn’t have to wait long to make good on their pledge. In September 1739, one of the largest rebellions by enslaved people in North American colonial history broke out near the Stono River in South Carolina, leading to the death of 25 colonists before it was crushed. The English blamed the Spanish promise of freedom for inspiring the rebels. A broader conflict between Britain and Spain, the War of Jenkins’ Ear, broke out soon after, and, early in 1740, James Oglethorpe, governor of the English colony of Georgia, attacked Florida and overwhelmed Fort Mose. The Black militia retreated to the Castillo de San Marcos, the Spanish fort in St. Augustine. They mounted a surprise attack in June 1740, reclaiming Fort Mose in a ruthless battle that came to be known as Bloody Mose. Their fort, however, had been destroyed, and the militia would remain in St. Augustine for the next 12 years.

In 1752, Florida Governor Fulgencio García de Solís decided to move the Black militia back to Fort Mose. This forced relocation was met with substantial resistance from militiamen, who, according to a report filed by García, expressed their “desire to live in complete liberty.” These soldiers had put down roots in the colonial capital and may have been wary of serving once again as the tip of the spear of Spanish defense. “Many of them had married in town, taken up trades, and had children,” says Deagan. Some of the men had wives of African descent, while others had married Native Americans or Spaniards. “They were probably living a much more comfortable life, within a larger social community, that they didn’t want to leave.” García claims that he “lightly” punished the unnamed leaders of the resistance and successfully relocated the militia members along with their wives and children to a spot a few hundred yards north of the original fort.

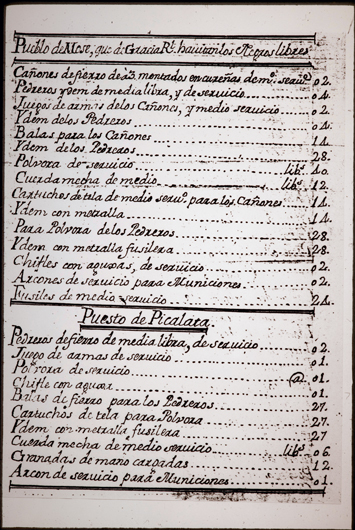

Back at Fort Mose, once again under Menéndez’s leadership, the militiamen built a second, larger fort, which was described in a 1759 report written by Father Juan Joseph de Solana, one of the parish priests assigned to minister to the community. The new fort had at least seven internal structures including a church, a priest’s residence, and a guard house. It was surrounded on three sides by earthen walls, measuring around 210 feet on a side, faced with clay and sod, and covered with thorns. The fort’s east side was left exposed to the neighboring waterway, which was called Mose Creek. A 10-foot-wide moat surrounded its walls, and several small cannons and swivel guns were mounted on its bastions. “It’s an odd-shaped fort with one whole side open to the creek,” says Deagan. “I assume they expected any invasion or attack to come from the landward side, and that’s where the guns would have been.”

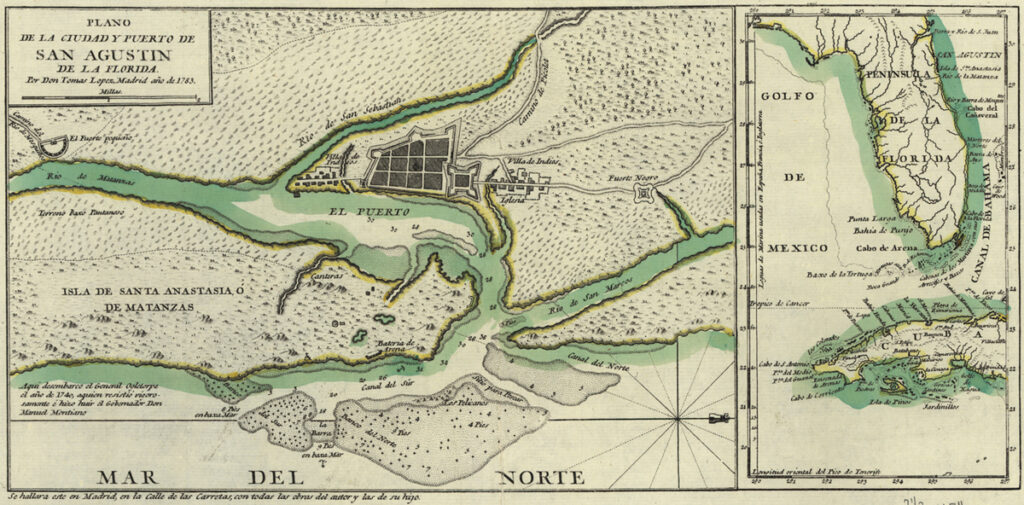

When archaeologists began to search for the remnants of Fort Mose, they had to contend with a landscape that was dramatically changed from that of the eighteenth century. In the 1880s, oil and railroad magnate Henry Flagler dredged the area where Fort Mose was located to provide fill for construction of a luxury hotel in St. Augustine. Today, this grand Spanish Renaissance Revival structure is the centerpiece of Flagler College. The dredging caused seawater to infiltrate Fort Mose and its environs, turning it into a salt marsh dotted with a few small islands. During test excavations in the early to mid-1970s on one of these islands, archaeologists unearthed eighteenth-century ceramics. By overlaying eighteenth-century maps on aerial photographs, Deagan concluded that this island was likely the site of the second fort, built in 1752. According to historical texts, ruins of the second fort were visible at least as late as the 1850s, and Deagan says it is possible Flagler intentionally spared the island to preserve them. Thermal imaging revealed what she believes to be the outlines of the original fort to the south, though it is completely underwater.

During excavations on the island in 1987 and 1988, a team led by Deagan unearthed traces of the moat, of clay-faced earthworks, and of supports for interior buildings, establishing that this was indeed the site of the second fort. Among the artifacts they discovered were a chain-link rosary fragment and several glass beads that may have been part of a rosary, hints of the emphasis placed on converting the Fort Mose community to Catholicism. Deagan points out that the Spanish treated Fort Mose in much the same manner as they did Native American missions in Florida, with a priest present to offer religious indoctrination. One of Governor García’s rationales for moving the militia back to Fort Mose in 1752 was his concern that their “spiritual backwardness” and “bad customs” would rub off on other residents of St. Augustine. Spanish authorities also addressed Menéndez as they did Native tribal chiefs, referring to other militia members as his subjects.

Deagan’s team found a range of eighteenth-century ceramics, military items such as gunflints and musket balls, materials for food preparation such as cooking pots and stones for grinding corn, and personal objects such as pipes and buttons, including a bone button in the process of being carved. What was most striking, though, was the paucity of precious objects. “We found almost no ornamental items or items of value,” says Deagan. “It was a life of privation.” One artifact that may be an exception is a silver medal. On one side is Saint Christopher, the patron saint of travelers, carrying the Christ child. On the other side, there is a compass rose showing the cardinal directions and intermediate points. A hole at the top of the image of Saint Christopher was filled in and, at some point, another hole was drilled to the right of the saint. The compass rose, which appears to have been added later, seems to have been intended for English speakers as a “W” is used to indicate west, not an “O” for the Spanish oeste. While the medal’s style suggests it likely dates to the eighteenth century, it was found on its own in the creek alongside the fort, making it difficult to determine whether it was deposited during the period when the Black militia was based there. “If it was someone at Mose that altered it,” says Deagan, “it would almost be evidence of rejection of Christianity because of the way its orientation was switched.” If the medal were hung from the original hole, the saint would have stood upright. Using the new hole, he would be turned on his side.

Spanish authorities envisioned Fort Mose as an agricultural as well as a military outpost that would grow enough corn, and possibly rice, to feed all of St. Augustine. Historical documents make clear that the settlement never produced sufficient crops to feed even itself and received meager food supplements from the government that also failed to stave off their hunger. This was surely part of the reason militia members resisted returning in 1752. “They said it wasn’t healthy there,” says Lee. “The government was requesting provisions for them, but they weren’t receiving them.” Remains unearthed by Deagan’s team, including those of fish, shellfish, turtles, rabbits, and deer, indicate that Fort Mose’s residents were making do with locally available wild animals. “This was living off the land,” says Deagan.

However, the current excavations at the site led by Lee, Ibarrola, and Davidson, which began in 2019, have unearthed cow and pig bones, suggesting that at least some livestock was being raised at Fort Mose and would have provided additional food. The team also found evidence that militia members had access to the occasional luxury item. They unearthed part of a bottle that contained an English patent medicine called Turlington’s Balsam of Life, which was marketed as a cure-all that could purportedly treat dozens of ailments from toothaches to pancreatitis. In the 1760s, a half-ounce bottle of the elixir cost the rough equivalent of $23 today and would have had to be illicitly smuggled into Florida as trade with the British was forbidden at the time. “It’s remarkable that these Africans, who were pretty poor by every stretch of the measure of the eighteenth century, were buying an expensive little bottle of medicine from London,” says Davidson. Ibarrola suggests that the residents of Fort Mose might have adapted the English medicine to their own ends. “Ritual practice doesn’t always have to look like a charm worn on the body,” she says. “Protective elixirs such as this might have been consumed by the militia members in order to help fortify their bodies and bind them together.”

In the summer of 2023, underwater excavations led by Meide revealed remnants of a wharf on the creek side of the fort, which may explain the absence of fortifications there. The team found two lines of large coquina stones, a local type of sedimentary stone composed of shells: one parallel to the shoreline and another jutting out into the waterway. These stones would have been footers for the structure. They also identified several well-preserved wooden pilings. The structure is difficult to date, though Meide suggests it was likely built by the Black militia, given the labor required to move such large stones into place. A wharf would also have been invaluable to the fort’s operation. “The fastest way to get to St. Augustine probably would have been by boat,” says Meide. “A small sailing vessel could end up getting there faster than a horse. And it would have been the easiest way to get large amounts of supplies there.” Meide adds that the Black militiamen would have been well acquainted with life on the water. “Enslaved Africans were brought from a maritime environment in West Africa to another maritime environment, the plantations of the Carolinas,” he says. “They knew how to operate watercraft, and once they escaped and were living a new life, it was again heavily taken up with waterfront activities.”

The Black militia remained at Fort Mose until 1763, when Spain ceded Florida to the British at the end of the French and Indian War. At this point, the Spanish moved Fort Mose’s population, along with that of the rest of the colony, to Cuba. They spent a few years in Regla, a fishing village near Havana, before being granted land in the rough frontier province of Matanzas. (See “Off the Grid: Ambrosio Cave, Cuba.”) “Each household is given two machetes, a donkey, and a bozal—a newly arrived, African-born, enslaved person—to use for clearing and settling this new land,” says Ibarrola. “But they are given pretty rocky territory and there isn’t a lot of success to be had there.” Within a decade or so, most of the families from Fort Mose had moved back to Regla. This likely included Menéndez, his wife, Ana María de Escovar, and their four children.

His apparent return to a more urban setting is the last that is known of Menéndez, who led a truly picaresque life. After the success of the militia under his leadership in the Battle of Bloody Mose in June 1740, he wrote a series of letters to the Spanish king of a sort known as méritos y servicios, or “merits and services,” seeking recognition and recompense for his exploits. “It’s part of the Spanish military tradition that once you’ve done something for the king, you send him this report and his obligation as a good monarch is to reward you,” says Landers. Menéndez received no reply, so he signed onto a Spanish corsair ship that engaged in raids on British vessels seeking treasure and goods to resupply war-ravaged Florida. Menéndez hoped to get to Havana and then to Spain, where he could make his case directly to the king. But, in July 1741, the ship carrying him was captured by the British, who took him to the Bahamas, where the admiralty court determined he should be sold into slavery—for the third time. It’s unclear exactly how Menéndez pulled it off, but by 1743, he was once again free and back in St. Augustine. “Did he escape?” asks Landers. “Was he ransomed by the Spanish? I don’t know. I’m still working on that.”

The British refurbished Fort Mose and used it during their occupation of Florida, which came to an end in 1783, when Spain regained control of the colony at the close of the American Revolution. Many Floridanos, or former Florida colonists, returned from Cuba, possibly including some members of the Fort Mose community—though not Menéndez, according to Landers’ research. The Spanish resumed their practice of welcoming fugitives from slavery to the colony until they acceded in 1790 to pressure from the new U.S. government and its secretary of state, Thomas Jefferson, to desist. Fort Mose remained a Spanish military outpost until 1812, when it was occupied by a group of Americans known as the Florida Patriots, who aimed to win the colony for the United States. In the process of quelling this rebellion, a Spanish schooner pelted the fort with cannon fire, setting it ablaze. Florida was ultimately acquired by the United States in 1819.

Descendants of the Fort Mose Black militiamen are now part of the broader African diaspora community in Cuba, and it’s unknown whether they identify with their ancestors who attained freedom in the Spanish colony of Florida. For the present-day Black community of St. Augustine, however, the site holds great significance. Thomas Jackson, president of the board of trustees of the St. Augustine Historical Society, recalls that while growing up in the segregated St. Augustine of the 1960s, he and other Black residents would visit the city’s Spanish fort, the Castillo de San Marcos, on Easter Sunday. Older members of the community would tell him, “We had a fort, too, at one time.” Jackson didn’t learn more about the Black fort—much less its name—until he went to college at Florida A&M University, a historically Black institution. Today, he says, the history of Fort Mose and its free Black militia is taught to Florida elementary school students. This is all the more important as the physical remnants of the fort face dire threats from rising sea levels, with little of the site likely to remain above water a decade or two from now. “We have fought long and hard to get the public school curriculum to acknowledge that Fort Mose was a part of the history of Florida,” Jackson says. “The story of Fort Mose is a story that must be told: We had a fort, too.”