From The Trenches

Turning Back the Human Clock

By KATHERINE SHARPE

Monday, December 17, 2012

For years, archaeologists and geneticists have been troubled by the fact that their time lines for key events in human evolution don’t always match up. While archaeologists rely on the dating of physical remains to determine when and how human beings spread across the globe, geneticists use a DNA “clock” based on the assumption that the human genome mutates at a constant rate. By comparing differences between modern and ancient DNA, geneticists then calculate when early humans diverged from other species and when human populations formed different genetic groups.

For years, archaeologists and geneticists have been troubled by the fact that their time lines for key events in human evolution don’t always match up. While archaeologists rely on the dating of physical remains to determine when and how human beings spread across the globe, geneticists use a DNA “clock” based on the assumption that the human genome mutates at a constant rate. By comparing differences between modern and ancient DNA, geneticists then calculate when early humans diverged from other species and when human populations formed different genetic groups.

The DNA clock is a powerful tool, but its conclusions—for example, that modern humans first emerged from Africa about 60,000 years ago—can disagree with archaeological evidence that shows signs of modern human activity well before that date at sites in regions as far-flung as Arabia, India, and China.

Now, new work, based on observation of the genetic differences between present-day parents and children, suggests that the genetic clock may actually run about twice as slowly as previously believed, at least for the last million years or so of primate history. In their review paper in the journal Nature Reviews Genetics, Aylwyn Scally and Richard Durbin of the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute in Hinxton, England, propose much earlier dates for watershed events in human evolution, which could help bring the genetic and archaeological records in line. For instance, a slower clock places the migration of modern humans out of Africa at around 120,000 years ago, which is more consistent with archaeological evidence.

The revised clock also supports archaeological signs of modern human activity from more than 60,000 years ago at sites such as Jwalapuram, India (“Stone Age India,” January/February 2010), and Liujiang, China—evidence that has often been dismissed by geneticists as impossible. While more work is needed to confirm the findings, Scally says that archaeologists who work on such sites should be excited: “It can no longer be said that the genetic evidence is unequivocally against them.”

Denisovan DNA

By ZACH ZORICH

Monday, December 17, 2012

A new technique for sequencing ancient DNA has allowed a multinational research team to reconstruct the genome of a person who lived in Siberia’s Denisova Cave between 30,000 and 82,000 years ago—with the same level of accuracy as genomes from modern people. This new DNA sequence gives researchers a clearer picture of how early hominins such as the Denisovans and Neanderthals were related to modern humans and to each other.

A new technique for sequencing ancient DNA has allowed a multinational research team to reconstruct the genome of a person who lived in Siberia’s Denisova Cave between 30,000 and 82,000 years ago—with the same level of accuracy as genomes from modern people. This new DNA sequence gives researchers a clearer picture of how early hominins such as the Denisovans and Neanderthals were related to modern humans and to each other.

The analysis showed that Denisovans were much more closely related to Neanderthals than to Homo sapiens, and that in spite of coming from a small population, they managed to contribute genes to modern populations in Island Southeast Asia and Australia. According to David Reich, a geneticist at Harvard Medical School and a member of the research team, the new DNA sequence also shows that Native Americans and people from East Asia have more Neanderthal DNA, on average, than Europeans. Archaeologists have long thought that the largest population of Neanderthals lived in Europe, so the finding complicates the picture of the way modern people and Neanderthals are related. Either there was a separate event in which Neanderthals interbred with people in Asia, or the genetic contribution of Neanderthals in Europe was diluted by later migrations of Homo sapiens.

Neutron Beams and Lead Shot

By NIKHIL SWAMINATHAN

Monday, December 17, 2012

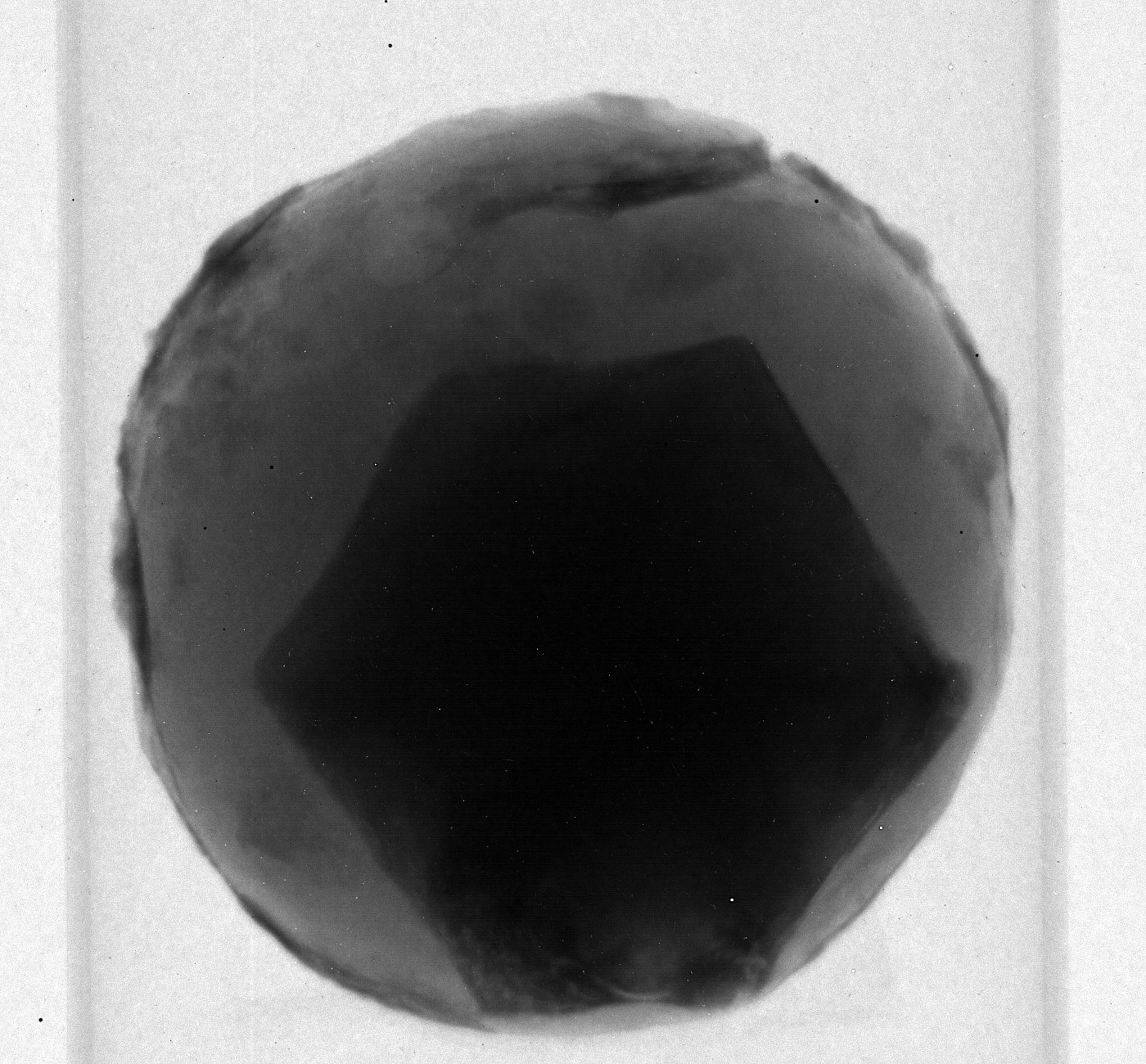

British researchers are going beyond standard X-rays to study nearly 500-year-old lead cannonballs found on the wreck of Mary Rose, a Tudor warship brought to the surface of the English Channel in 1982. The ship sank when the British fleet squared off with the French during the Battle of the Solent in 1545.

British researchers are going beyond standard X-rays to study nearly 500-year-old lead cannonballs found on the wreck of Mary Rose, a Tudor warship brought to the surface of the English Channel in 1982. The ship sank when the British fleet squared off with the French during the Battle of the Solent in 1545.

Using neutron-based imaging, which employs beams of the neutral subatomic particles that can pass through lead, the team has developed 2-D and 3-D renderings that reveal the Mary Rose’s cannonballs had lumps of iron in them. Why was the iron used? Possibly to save on expensive lead or because it altered the flight or impact of the projectiles.

According to battlefield archaeologist Glenn Foard of the University of Huddersfield, Mary Rose’s 1,600 rounds of unfired shot can help researchers understand state-of-the-art weaponry in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Says Foard, “We can compare it to the much rarer battlefield finds of projectiles which have firing and impact evidence telling us something of the guns that fired them.”

Site of a Forgotten War

By JUDE ISABELLA

Monday, December 17, 2012

In the remote mountains of southwestern Oregon, researchers have uncovered a pre–Civil War battlefield that was lost for more than a century and a half. The Battle of Hungry Hill was a pivotal fight during the Rogue River Wars of 1855 to 1856, a conflict between Oregon settlers and Native Americans. The battle, a defeat for the U.S. Army and a local militia, prompted the government to evict the native population from Oregon’s Rogue and Umpqua Valleys.

In the remote mountains of southwestern Oregon, researchers have uncovered a pre–Civil War battlefield that was lost for more than a century and a half. The Battle of Hungry Hill was a pivotal fight during the Rogue River Wars of 1855 to 1856, a conflict between Oregon settlers and Native Americans. The battle, a defeat for the U.S. Army and a local militia, prompted the government to evict the native population from Oregon’s Rogue and Umpqua Valleys.

For years, pioneer family stories led researchers searching for evidence of the battle in the wrong direction. However, archaeological surveys, according to Mark Tveskov, an archaeologist with Southern Oregon University, eventually identified the location where it had been fought. During the research, which began in 2009, Tveskov found previously unknown primary documentation, including a front-page article in the New York Herald, published 12 days after the battle concluded on October 31, 1855, and eyewitness accounts. This led the team to 24 square miles of the Grave Creek Hills, several miles northwest of the spot where the battle was previously thought to have taken place.

In September, the team turned up three artifacts that match weaponry used by the U.S. Army during the mid-nineteenth century—two .69 caliber lead musketballs and a lead stopper from a gunpowder container. Tveskov hopes to uncover more details, which might, among other things, corroborate two historical accounts of a Native American sniper picking off the majority of the Army’s 39 casualties.

Maya Mural Miracle

By ZACH ZORICH

Monday, December 17, 2012

Lucas Asicona Ramírez probably had no idea that he was embarking on an archaeological excavation five years ago when he began scraping down the plaster on the walls of his 300-year-old home in Chajul, Guatemala. But his renovation uncovered a series of murals that had been painted by his Ixil Maya ancestors in the years after the Spanish conquest. Some of the paintings depict what archaeologists Lars Frühsorge, Jarosław Źrałka, and William Saturno believe to be a ritual called the Dance of Conquest. The people in this painting seem to be Maya, yet wear some pieces of European clothing. The seated figures are playing instruments while the figure on the right, wearing a jaguar skin and cape, dances.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Top 10 Discoveries of 2012

Neolithic Europe's Remote Heart

The Water Temple of Inca-Caranqui

Letter from France

From The Trenches

The Rehabilitation of Richard III

Masked Men

Fixing Ancient Toothaches

Off the Grid

Obsidian and Empire

Ancient Alchemy?

Kidnapped in Copenhagen

The Emperor’s Orchids

Nazi Iron Man Buddha?

Maya Mural Miracle

Neutron Beams and Lead Shot

Site of a Forgotten War

Denisovan DNA

Turning Back the Human Clock

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement