From The Trenches

Off the Grid

By MALIN GRUNBERG BANYASZ

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

Saint Thomas has its share of delights—beaches, food, snorkeling—but it is also home to the only urban archaeological dig in the Caribbean. The Magens Site is a house compound in the Kongens Quarter of Charlotte Amalie, the capital and largest city in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The walled compound dates to the early nineteenth century and rests among other historic properties in the area known as Blackbeard’s Hill. In the 1820s, the site was home to Major Joachim Melchior Magens II, a Danish colonial official, and his children and other relatives. Douglas V. Armstrong, an archaeologist from Syracuse University, is examining the material culture left by the Magens family and their tenants and servants for insight into life in a bustling Caribbean port town. “Because the compound was completely intact and so little of it had been altered since the nineteenth century, it is an excellent site for archaeological investigation,” Armstrong says.

Saint Thomas has its share of delights—beaches, food, snorkeling—but it is also home to the only urban archaeological dig in the Caribbean. The Magens Site is a house compound in the Kongens Quarter of Charlotte Amalie, the capital and largest city in the U.S. Virgin Islands. The walled compound dates to the early nineteenth century and rests among other historic properties in the area known as Blackbeard’s Hill. In the 1820s, the site was home to Major Joachim Melchior Magens II, a Danish colonial official, and his children and other relatives. Douglas V. Armstrong, an archaeologist from Syracuse University, is examining the material culture left by the Magens family and their tenants and servants for insight into life in a bustling Caribbean port town. “Because the compound was completely intact and so little of it had been altered since the nineteenth century, it is an excellent site for archaeological investigation,” Armstrong says.

The site

Spread across 23 terraces, the Magens property consists of several historic buildings, including the kitchen, tenant quarters, slave/servant quarters, and two houses occupied by clerks and managers, as well as the ruins of the Magens House, where Magens and his family lived. The house is, in fact, the only building from the complex that is no longer intact—it was destroyed by Hurricane Marilyn in 1995. (Plans are underway to rebuild the house based on archaeological evidence.) The Magens compound and the harbor can be viewed from an overlook down the hill from Skytsborg Tower (popularly known as Blackbeard’s Castle).

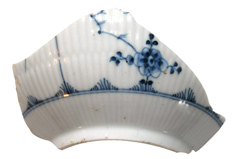

The property’s current owner, Michael Ball, has restored many of the nineteenth-century buildings and offers heritage tours. In 2007, Armstrong and his team began their excavations, which revealed a diverse community and a complex port economy. Artifacts include everything from high-status items, such as Danish porcelain, to a range of local and regionally produced earthenware and Moravian ware pottery used by the servants. The laborers also operated their own cottage industry producing bone buttons from animal ribs, and hundreds of bone button blanks have been recovered.

The property’s current owner, Michael Ball, has restored many of the nineteenth-century buildings and offers heritage tours. In 2007, Armstrong and his team began their excavations, which revealed a diverse community and a complex port economy. Artifacts include everything from high-status items, such as Danish porcelain, to a range of local and regionally produced earthenware and Moravian ware pottery used by the servants. The laborers also operated their own cottage industry producing bone buttons from animal ribs, and hundreds of bone button blanks have been recovered.

While you’re there

If you can peel yourself away from the beach, Saint Thomas is full of historic sights and wonderful shopping. Check out the 99 Steps, which were built in the mid-1700s, using ballast stones from Danish ships. Fun fact: There are actually 103 steps! Other sights include the historic synagogue of Beracha Veshalom Vegmiluth Hasidim. Built in 1796, it is the oldest synagogue in continuous use under the American flag—and it is probably the only one in the United States with a sand floor. French impressionist painter Camille Pissarro, who was born on Saint Thomas, and his father were members of its congregation. When you’re ready to take a break from sightseeing, the restaurants nestled in the city’s hillsides provide breathtaking views of the harbor at night.

Fixing Ancient Toothaches

By ZACH ZORICH

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

Scientists have recently uncovered evidence of a couple of instances of ingenious dental work in the ancient world. A team led by Federico Bernardini of the International Center for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, Italy, used a variety of techniques including CT scans and mass spectrometry to show that a 6,500-year-old skull found at the site of Lonche in Slovenia contains a cracked tooth that had been filled with beeswax—the oldest dental filling yet discovered. A similarly inventive technique was used on an Egyptian man whose mummified body dates to around 2,100 years ago. Andrew Wade of the University of Western Ontario led a group of researchers who found that the man had numerous cavities, the largest of which had been packed with linen. Unfortunately, the idea of using woven plant fibers to make dental floss was still millennia away.

Scientists have recently uncovered evidence of a couple of instances of ingenious dental work in the ancient world. A team led by Federico Bernardini of the International Center for Theoretical Physics in Trieste, Italy, used a variety of techniques including CT scans and mass spectrometry to show that a 6,500-year-old skull found at the site of Lonche in Slovenia contains a cracked tooth that had been filled with beeswax—the oldest dental filling yet discovered. A similarly inventive technique was used on an Egyptian man whose mummified body dates to around 2,100 years ago. Andrew Wade of the University of Western Ontario led a group of researchers who found that the man had numerous cavities, the largest of which had been packed with linen. Unfortunately, the idea of using woven plant fibers to make dental floss was still millennia away.

The Rehabilitation of Richard III

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

UPDATE (February 4, 2013): This story from ARCHAEOLOGY's January/February 2013 issue discusses the excavation of a site known as Greyfriars, under a Liecester parking lot, and the possibility that skeletal remains found there are those of King Richard III. DNA evidence, which was being analyzed at press time, has now confirmed that the bones are in fact those of the former King of England.

UPDATE (February 4, 2013): This story from ARCHAEOLOGY's January/February 2013 issue discusses the excavation of a site known as Greyfriars, under a Liecester parking lot, and the possibility that skeletal remains found there are those of King Richard III. DNA evidence, which was being analyzed at press time, has now confirmed that the bones are in fact those of the former King of England.

Pity poor Richard. Last of the House of York, last king of the Plantagenet line, last English monarch to die in battle. Richard III (r. 1483–1485) carries the most damning of reputations. His image as a villain—deformed of body and twisted of mind—has been firmly established, first by historians loyal to his successors (the Tudors), and later in literature and on the stage and screen. He is known to have seized the throne from his young nephews after the death of his brother, and it is rumored that he even had them killed. Thomas More, the Tudor historian, described him as “ill featured of limes, croke backed, his left shoulder much higher then his right.” Later, a century after his death, Shakespeare gave him few redeeming qualities, and this to say of himself: “And thus I clothe my naked villainy / With odd old ends, stol’n out of holy writ / And seem a saint, when most I play the devil.”

A reputation so bad practically begs for a reevaluation. Five hundred years after his death, Richard III finally seems to have passionate defenders and a good press team. Philippa Langely is a screenwriter and member of the Richard III Society, a group dedicated to rehabbing the king’s shabby image. To that end, she spent several years raising funds for the excavation of a parking lot in Leicester thought to have been the site of Greyfriars, the long-demolished friary where Richard III was supposedly buried. University of Leicester Archaeological Services (ULAS) was commissioned for the dig, and the field evaluation and excavations took place in September 2012.

In rapid succession, archaeologists found a trail of clues to what may be one of the more significant discoveries in English archaeology: the remains of a notorious, anointed King of England. The finds—punctuated by a dramatic series of press releases—attracted worldwide notice. “I found the project an interesting one, if I’m honest, because of the opportunity to learn more about the site of the Franciscan friary in which Richard III was said to have been buried, rather than actually finding the remains of the king, which I thought was a long shot,” says Richard Buckley, director of ULAS. “Of course finding Richard III would be the icing on the cake, but given that we had no reliable information about the layout of the friary buildings, let alone the position of the church, and a very restricted area available for trenching, it did not look likely.”

Even before anything was found, the excavation drew enormous public and media interest, leading the University of Leicester, the Leicester City Council, and the Richard III Society to keep the press and public apprised almost daily—an atypical practice in a field in which time, research, and analysis are often needed to understand finds. “It was unusual to be watched so closely by the press—I never expected there to be so much interest and was completely taken by surprise by the numbers of journalists who appeared on-site on the launch day,” says Buckley, who has excavated in the city for 30 years. “In some ways, this is what drove the strategy for regular updates as the work proceeded.”

Even before anything was found, the excavation drew enormous public and media interest, leading the University of Leicester, the Leicester City Council, and the Richard III Society to keep the press and public apprised almost daily—an atypical practice in a field in which time, research, and analysis are often needed to understand finds. “It was unusual to be watched so closely by the press—I never expected there to be so much interest and was completely taken by surprise by the numbers of journalists who appeared on-site on the launch day,” says Buckley, who has excavated in the city for 30 years. “In some ways, this is what drove the strategy for regular updates as the work proceeded.”

For those who follow archaeological discoveries, the finds came with breathless speed. On September 5, archaeologists reported they had found traces of the friary church, including a tiled floor, walls, and architectural fragments. Then, on September 7, they reported finding fragments of window tracery thought to be from the church, as well as paving stones from a garden that occupied the area after the friary had been demolished in the 1530s. In 1612, this garden was reported to have held a stone pillar that identified it as the burial place of Richard III.

Masked Men

By MATTHEW BRUNWASSER

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

Under a third-century a.d. Roman fortress near the village of Ilısu in southeastern Turkey, archaeologist Erkan Atay and his team from the Mardin Museum recently uncovered two theater masks of a type rarely found in Turkey. Atay believes that the masks, one of which is made of bronze and the other of iron, were not intended for formal theatrical performances, but may have been used by young male actors entertaining during sporting events.

Under a third-century a.d. Roman fortress near the village of Ilısu in southeastern Turkey, archaeologist Erkan Atay and his team from the Mardin Museum recently uncovered two theater masks of a type rarely found in Turkey. Atay believes that the masks, one of which is made of bronze and the other of iron, were not intended for formal theatrical performances, but may have been used by young male actors entertaining during sporting events.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Top 10 Discoveries of 2012

Neolithic Europe's Remote Heart

The Water Temple of Inca-Caranqui

Letter from France

From The Trenches

The Rehabilitation of Richard III

Masked Men

Fixing Ancient Toothaches

Off the Grid

Obsidian and Empire

Ancient Alchemy?

Kidnapped in Copenhagen

The Emperor’s Orchids

Nazi Iron Man Buddha?

Maya Mural Miracle

Neutron Beams and Lead Shot

Site of a Forgotten War

Denisovan DNA

Turning Back the Human Clock

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Confirmation of the remains as Richard III’s will have to wait for the results of mitochondrial DNA tests comparing the skeleton’s genetic material with that of Michael Ibsen, a Canadian who is a seventeenth great-grand-nephew of the king. The results are likely to be announced in conjunction with a television special produced alongside the excavation. ULAS’s seasoned archaeological team has very clearly stated that the discovery of Richard III’s remains has always been more a hope than an expectation. They accept the risk that the early press coverage will prove to be only hype if the remains are shown not to be the king’s.

Confirmation of the remains as Richard III’s will have to wait for the results of mitochondrial DNA tests comparing the skeleton’s genetic material with that of Michael Ibsen, a Canadian who is a seventeenth great-grand-nephew of the king. The results are likely to be announced in conjunction with a television special produced alongside the excavation. ULAS’s seasoned archaeological team has very clearly stated that the discovery of Richard III’s remains has always been more a hope than an expectation. They accept the risk that the early press coverage will prove to be only hype if the remains are shown not to be the king’s.