From The Trenches

Nazi Iron Man Buddha?

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

The world is full of strange, unmoored historical artifacts. Some come with puzzling, mysterious origins and interesting, if unconfirmed, auras of intrigue. Take the Nazi Buddhist iron man from outer space. This 10-inch-tall, 24-pound sculpture apparently depicting a Buddha figure with scale armor bearing a swastika has some pretty dubious provenance: It’s rumored to have been found during Nazi expeditions to Tibet, perhaps part of an effort to establish Germany’s Aryan roots. (Prior to its life as the calling card of National Socialism, the swastika enjoyed thousands of years as a positive symbol in South Asian religions.) Recent mineralogical analysis by German, Australian, and Austrian researchers now shows that the statue may have been sculpted from a meteorite that fell somewhere along the Siberian-Mongolian border. The paper, in Meteoritics and Planetary Science, also sparked heated debate about the statue’s origins. Buddhist scholar Achim Bayer at Dongguk University in Seoul, Korea, says that the statue is most likely just decades (rather than centuries) old, perhaps made after WWII for the lucrative market in Nazi memorabilia.

The world is full of strange, unmoored historical artifacts. Some come with puzzling, mysterious origins and interesting, if unconfirmed, auras of intrigue. Take the Nazi Buddhist iron man from outer space. This 10-inch-tall, 24-pound sculpture apparently depicting a Buddha figure with scale armor bearing a swastika has some pretty dubious provenance: It’s rumored to have been found during Nazi expeditions to Tibet, perhaps part of an effort to establish Germany’s Aryan roots. (Prior to its life as the calling card of National Socialism, the swastika enjoyed thousands of years as a positive symbol in South Asian religions.) Recent mineralogical analysis by German, Australian, and Austrian researchers now shows that the statue may have been sculpted from a meteorite that fell somewhere along the Siberian-Mongolian border. The paper, in Meteoritics and Planetary Science, also sparked heated debate about the statue’s origins. Buddhist scholar Achim Bayer at Dongguk University in Seoul, Korea, says that the statue is most likely just decades (rather than centuries) old, perhaps made after WWII for the lucrative market in Nazi memorabilia.

The Emperor’s Orchids

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

The first fragments of the remarkable ancient Roman monument called the Ara Pacis (“Altar of Peace”) were found in the early sixteenth century. For the next four hundred years, the large marble altar, built to commemorate the emperor Augustus’ victories in Gaul and expansion into Spain in the first century b.c., was reassembled as pieces resurfaced until it was nearly completed in 1938. Since then, scholars have examined the altar’s heavily decorated exterior, attempting to identify the mythological and historical figures represented. However, until several years ago when archaeologist Giulia Caneva of the University of Rome was asked whether the plants and flowers represented on the Ara Pacis were faithful representations or purely fantastical—and if she could identify them—no one had carefully studied the monument’s vegetation in such detail.

The first fragments of the remarkable ancient Roman monument called the Ara Pacis (“Altar of Peace”) were found in the early sixteenth century. For the next four hundred years, the large marble altar, built to commemorate the emperor Augustus’ victories in Gaul and expansion into Spain in the first century b.c., was reassembled as pieces resurfaced until it was nearly completed in 1938. Since then, scholars have examined the altar’s heavily decorated exterior, attempting to identify the mythological and historical figures represented. However, until several years ago when archaeologist Giulia Caneva of the University of Rome was asked whether the plants and flowers represented on the Ara Pacis were faithful representations or purely fantastical—and if she could identify them—no one had carefully studied the monument’s vegetation in such detail.

Soon Caneva discovered that the flowers were both fantasies and what she calls “extremely realistic” representations. The most surprising faithfully depicted species were two types of orchids, both of which are native to the Mediterranean. Until Caneva’s research, orchids were unknown in ancient art and had only been identified on works dating from the Renaissance and later. Caneva is continuing to decode the altar’s highly symbolic language of flowers and vegetation, which is part of the political message of this enduring monument to Augustus’ lineage and power.

Ancient Alchemy?

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

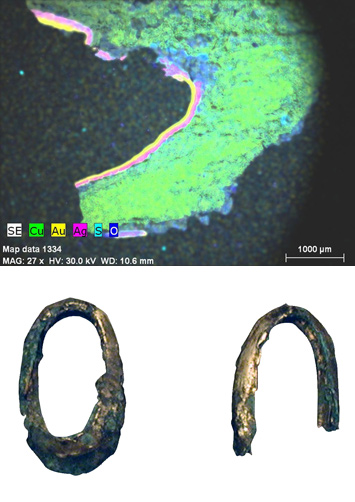

To the naked eye, the pendant once looked like solid gold, but anthropologist David Peterson of Idaho State University knows its secret. Using a powerful scanning electron microscope at the Center for Archaeology, Materials and Applied Spectroscopy, Peterson discovered that more than 3,500 years ago, a craftsman in the Russian steppes made the ornament appear to be solid gold by using a miniscule amount of the precious metal and a great deal of chemical knowledge. Peterson believes that the Late Bronze Age metalworker, a member of the Srubnaya people, employed a technique known as depletion gilding. The pendant was made with a core of (now corroded) copper, which was covered with a very thin foil of electrum (a mixture of gold and silver). Before or after wrapping the pendant, the surface of the foil may have been covered for several days in a solution of salt and/or other minerals that are corrosive to silver. The silver would have become a black scale that was then washed away—leaving a micrometers-thick layer of gold on the surface, burnished to look even richer.

To the naked eye, the pendant once looked like solid gold, but anthropologist David Peterson of Idaho State University knows its secret. Using a powerful scanning electron microscope at the Center for Archaeology, Materials and Applied Spectroscopy, Peterson discovered that more than 3,500 years ago, a craftsman in the Russian steppes made the ornament appear to be solid gold by using a miniscule amount of the precious metal and a great deal of chemical knowledge. Peterson believes that the Late Bronze Age metalworker, a member of the Srubnaya people, employed a technique known as depletion gilding. The pendant was made with a core of (now corroded) copper, which was covered with a very thin foil of electrum (a mixture of gold and silver). Before or after wrapping the pendant, the surface of the foil may have been covered for several days in a solution of salt and/or other minerals that are corrosive to silver. The silver would have become a black scale that was then washed away—leaving a micrometers-thick layer of gold on the surface, burnished to look even richer.

Depletion gilding has been found in artifacts from the third-millennium b.c. royal cemetery of Ur in Mesopotamia and the pre-Columbian Andes. However, the pendant, which was excavated in the 1990s in a young girl’s grave at the site of Spiridonovka II, would be the earliest known example from the Eurasian steppes. Peterson’s research on ancient Eurasian steppe metallurgy began while he was a member of the Samara Valley Project, sponsored by Hartwick College and the Institute for the History and Archaeology of the Volga. “Evidence of depletion gilding at this time in this area is a big surprise and stands to greatly impact our understanding of the technical sophistication of Srubnaya pastoralists,” says Peterson. “A kind of technological sleight of hand or dissembling was used in covering the copper ornaments with a very thin gold and silver foil, and then altering the surface to make it look more like pure gold, a strong indication of the high valuation of gold.”

Depletion gilding has been difficult to identify because the principle used—the removal of material rather than its addition—differs from modern gold plating, which uses chemicals or electrolysis to deposit gold on an object’s surface. The technique also differs from other ancient gilding practices, such as hammering gold foil onto an object without additional preparation, or diffusion bonding (used by the Greeks and Romans), which involves attaching gold through the application of heat and pressure.

Kidnapped in Copenhagen

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

Kongens Nytorv, a major square in Copenhagen, has offered evidence of a dark chapter in the exploration of the northern latitudes, according to Jens Winter Johannsen, an archaeologist at the Museum of Copenhagen. Excavations in the square uncovered a piece of a Thule bird spear from Greenland in what was once a moat around the city. There is one obvious way the seventeenth-century spear prong could have made it across the North Atlantic: kidnapping. It wasn’t uncommon for European explorers to bring home natives, often against their will, as novelties or to prove tales of discovery. The fragment, made of bone, could have been a mariner’s souvenir, but also could have belonged to one of the 19 Greenlanders known to have been forcibly kidnapped by Danes that century. According to Johannsen, “The small implement found at Kongens Nytorv thus illustrates a cruel story of some of the consequences of Danish ambitions as a great power.”

Kongens Nytorv, a major square in Copenhagen, has offered evidence of a dark chapter in the exploration of the northern latitudes, according to Jens Winter Johannsen, an archaeologist at the Museum of Copenhagen. Excavations in the square uncovered a piece of a Thule bird spear from Greenland in what was once a moat around the city. There is one obvious way the seventeenth-century spear prong could have made it across the North Atlantic: kidnapping. It wasn’t uncommon for European explorers to bring home natives, often against their will, as novelties or to prove tales of discovery. The fragment, made of bone, could have been a mariner’s souvenir, but also could have belonged to one of the 19 Greenlanders known to have been forcibly kidnapped by Danes that century. According to Johannsen, “The small implement found at Kongens Nytorv thus illustrates a cruel story of some of the consequences of Danish ambitions as a great power.”

Obsidian and Empire

By ZACH ZORICH

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

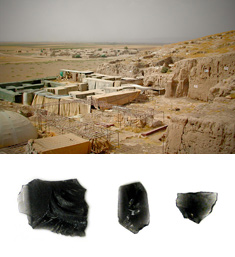

Three small and apparently unremarkable pieces of obsidian, found in the palace courtyard of the ancient city of Urkesh in modern-day Syria, are changing ideas about trade networks at the height of the Akkadian Empire’s power. Urkesh sits near a mountain pass by the border between the Bronze Age Hurrian and Akkadian empires—putting it in a natural position to be a trading center. According to Ellery Frahm of the University of Sheffield and Joshua Feinberg of the University of Minnesota, decades of studies had shown that nearly all of the obsidian used in Urkesh and sites throughout Mesopotamia came from volcanoes in what is now eastern Turkey. Frahm, however, tested this by analyzing the magnetic properties of 97 pieces of obsidian found throughout the city and learned that three of the pieces came from a volcano located much farther away, in central Turkey. These pieces were dated to around 2440 B.C., about the time that Emperor Naram-Sin expanded the Akkadian Empire to its peak influence. Frahm believes that the Akkadians were expanding their trade networks into new territory. The three pieces of obsidian may have been from items traded along with more valuable goods, such as metals. According to Frahm, “It shows that they were tapping into a trade network at that time that they weren’t using before or after.”

Three small and apparently unremarkable pieces of obsidian, found in the palace courtyard of the ancient city of Urkesh in modern-day Syria, are changing ideas about trade networks at the height of the Akkadian Empire’s power. Urkesh sits near a mountain pass by the border between the Bronze Age Hurrian and Akkadian empires—putting it in a natural position to be a trading center. According to Ellery Frahm of the University of Sheffield and Joshua Feinberg of the University of Minnesota, decades of studies had shown that nearly all of the obsidian used in Urkesh and sites throughout Mesopotamia came from volcanoes in what is now eastern Turkey. Frahm, however, tested this by analyzing the magnetic properties of 97 pieces of obsidian found throughout the city and learned that three of the pieces came from a volcano located much farther away, in central Turkey. These pieces were dated to around 2440 B.C., about the time that Emperor Naram-Sin expanded the Akkadian Empire to its peak influence. Frahm believes that the Akkadians were expanding their trade networks into new territory. The three pieces of obsidian may have been from items traded along with more valuable goods, such as metals. According to Frahm, “It shows that they were tapping into a trade network at that time that they weren’t using before or after.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Top 10 Discoveries of 2012

Neolithic Europe's Remote Heart

The Water Temple of Inca-Caranqui

Letter from France

From The Trenches

The Rehabilitation of Richard III

Masked Men

Fixing Ancient Toothaches

Off the Grid

Obsidian and Empire

Ancient Alchemy?

Kidnapped in Copenhagen

The Emperor’s Orchids

Nazi Iron Man Buddha?

Maya Mural Miracle

Neutron Beams and Lead Shot

Site of a Forgotten War

Denisovan DNA

Turning Back the Human Clock

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement