Features

The Water Temple of Inca-Caranqui

By JULIAN SMITH

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

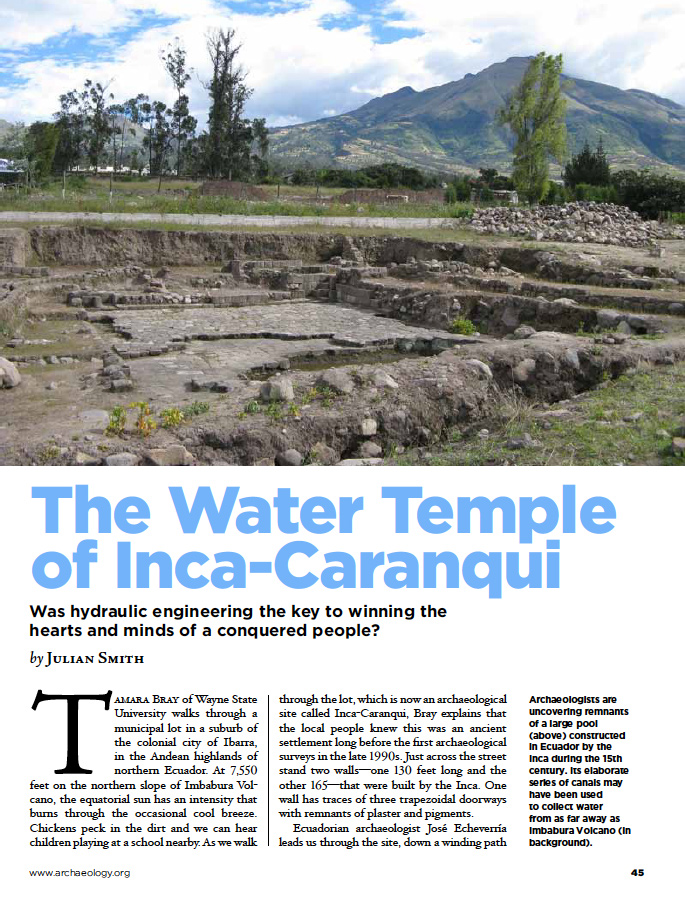

Tamara Bray of Wayne State University walks through a municipal lot in a suburb of the colonial city of Ibarra, in the Andean highlands of northern Ecuador. At 7,550 feet on the northern slope of Imbabura Volcano, the equatorial sun has an intensity that burns through the occasional cool breeze. Chickens peck in the dirt and we can hear children playing at a school nearby. As we walk through the lot, which is now an archaeological site called Inca-Caranqui, Bray explains that the local people knew this was an ancient settlement long before the first archaeological surveys in the late 1990s. Just across the street stand two walls—one 130 feet long and the other 165—that were built by the Inca. One wall has traces of three trapezoidal doorways with remnants of plaster and pigments.

Ecuadorian archaeologist José Echeverría leads us through the site, down a winding path that follows the low outlines of partially excavated walls. He explains that, in 2006, he was helping clear debris left over from a brickmaking operation when he uncovered some Inca masonry at the east end of the site, which turned out to be part of a large ceremonial pool about 33 by 55 feet in size. It was dug to a depth of four to five feet below the modern ground level and was surrounded by walls about three feet high. The walls and floor were made of finely cut and fitted stone.

Bray and Echeverría believe the pool may date to a period in the early 1500s, shortly after the Inca ruler Huayna Capac had concluded a 10-year war of conquest against the local people, the Caranqui. Legend has it that Huayna Capac had every adult male Caranqui executed. Their bodies were thrown into a lake known today as Yahuarcocha, or the “Lake of Blood,” on Ibarra’s northeast edge. Spanish chronicler Pedro Cieza de León estimated the conflict left 20,000 to 50,000 Caranqui dead.

Bray and Echeverría believe the pool may date to a period in the early 1500s, shortly after the Inca ruler Huayna Capac had concluded a 10-year war of conquest against the local people, the Caranqui. Legend has it that Huayna Capac had every adult male Caranqui executed. Their bodies were thrown into a lake known today as Yahuarcocha, or the “Lake of Blood,” on Ibarra’s northeast edge. Spanish chronicler Pedro Cieza de León estimated the conflict left 20,000 to 50,000 Caranqui dead.

Bray and Echeverría think that in the aftermath of that bloodshed, the Inca built the pool as part of a construction project that was meant to demonstrate their power to their new Caranqui subjects. The ceremonial pool would have represented a considerable investment of wealth and labor by the Inca. It also would have showed their skill as engineers by bringing water from as far as five and a half miles away and demonstrated their mastery over a resource with powerful religious symbolism.

|

Sidebar:

|

Machu Picchu's

Stairway of

Fountains

|

Neolithic Europe's Remote Heart

By KATE RAVILIOUS

Thursday, March 19, 2015

In 2002, Ola and Arnie Tait decided they wanted to change the view from their kitchen window. Rather than staring at a sheep pasture, they envisioned looking out onto a wildflower meadow full of poppies, cornflowers, buttercups, and singing birds. Their farm, on Orkney, a remote archipelago of 70 islands 10 miles off the north coast of Scotland, sits in a stunning natural setting, on a narrow strip of land between two sparkling lochs, and is equidistant from two of the most significant Neolithic stone circle monuments: the Standing Stones of Stenness and the Ring of Brodgar, each less than a mile away. In 2003, the Taits plowed their field in preparation for planting that meadow. Just as they rounded the last bend, the plow brought up a surprise: a notched slab of stone. They showed the find to Orkney’s regional archaeologist, Julie Gibson, who thought it might be a side panel from a Bronze Age stone coffin. “This find implied that there were human remains under the field, so a test trench was opened,” says Roy Towers, an archaeologist at the Orkney campus of the University of the Highlands and Islands.

Years have passed and the Taits are still not looking at their wildflower meadow. Rather, they have a prime view of one of the most spectacular Neolithic ceremonial complexes ever discovered. Spanning a millennium of activity beginning around 5,000 years ago, these exquisitely preserved buildings, including foundations and low walls, are revealing how Neolithic society changed over time, and why Orkney—despite its seemingly remote location—was at the center of Neolithic Europe. “Thank goodness the Taits didn’t use a deep plow, or else we’d have been looking at a pile of rubble,” says Towers.

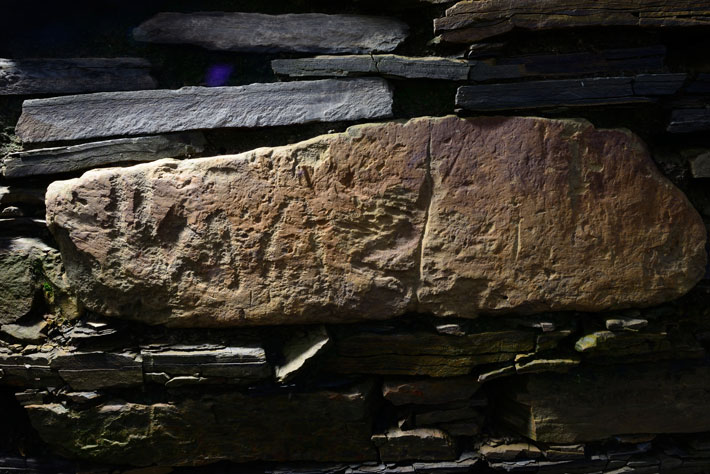

Instead of digging up a Bronze Age coffin in the 2003 test trench, as they expected, the archaeologists uncovered part of a finely crafted Neolithic wall. “It had sharp internal angles, beautifully coursed stonework, and fine corner buttresses,” explains Nick Card of the Orkney Research Centre for Archaeology, dig director at the site, now known as the “Ness of Brodgar.”

The next year the archaeologists embarked on a season of digging test pits and trial trenches across the field. To their delight they encountered incredible Neolithic stonework in virtually every hole. Realizing that they were looking at a major Neolithic complex, Card and his colleagues decided to open up a larger area. For the last five years, he and his team have dug for six weeks every summer. So far they have identified more than 20 structures, and observed even more through geophysical tests such as magnetometer surveys and ground-penetrating radar, all enclosed by the remains of a thick boundary wall delineating a six-acre complex—the size of three soccer pitches. Carbon dating of animal bone, wood, and charcoal indicates at least 1,000 years of continuous activity, from around 3300 to 2300 B.C. The site was likely in use for even longer. “In many cases one structure is built on top of another structure. The whole thing is sitting on a jelly of earlier structures,” says Card. “What we are seeing really is just the tip of the iceberg.” So far the archaeologists have concentrated on a small portion of the site—just 10 percent of the total area—and only excavated down to the floor level of the uppermost structures. In the layers of building foundations, Card and his team are seeing a clear progression in building style and architecture—a pattern they think may reflect some of the changes occurring in Neolithic society over that time.

|

Sidebar:

|

Sidebar:

|

Orkney's Artists

|

Tomb Architecture

|

Top 10 Discoveries of 2012

By THE EDITORS

Wednesday, December 19, 2012

Any discussion of archaeology in the year 2012 would be incomplete without mention of the much-talked-about end of the Maya Long Count calendar and the apocalyptic prophecies it has engendered. With that in mind, as 2013 approaches, the year’s biggest discovery may actually be that we’re all still here—at least that’s what the editors of Archaeology continue to bet on.

Any discussion of archaeology in the year 2012 would be incomplete without mention of the much-talked-about end of the Maya Long Count calendar and the apocalyptic prophecies it has engendered. With that in mind, as 2013 approaches, the year’s biggest discovery may actually be that we’re all still here—at least that’s what the editors of Archaeology continue to bet on.

However, you won’t find that story on our Top 10 list. We steered clear of speculation and focused, instead, on singular finds—the stuff, if you will—the material that comes out of the earth and changes what we thought we knew about the past. Here you’ll see discoveries that range from a work of Europe’s earliest wall art to the revelation that Neanderthals, our closest relatives, selectively picked and ate medicinal plants, and from the unexpected discovery of a 20-foot Egyptian ceremonial boat to the excavation of stunning masks that decorate a Maya temple and tell us of a civilization’s relation to the cosmos.

Then there are the discoveries that just made us wonder. What drove someone to wrap their valuables in a cloth and hide them almost 2,000 years ago? And why were people in Bronze Age Scotland gathering bones and burying them in bogs?

The finds span the last 50,000 years and cover territories from the cradle of civilization to what is today one of the world’s most populous cities. These are a few of the discoveries that speak to us of both our record of ingenuity and our humanity. The enduring question is always: Were the people behind the evidence anything like us?

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Top 10 Discoveries of 2012

Neolithic Europe's Remote Heart

The Water Temple of Inca-Caranqui

Letter from France

From The Trenches

The Rehabilitation of Richard III

Masked Men

Fixing Ancient Toothaches

Off the Grid

Obsidian and Empire

Ancient Alchemy?

Kidnapped in Copenhagen

The Emperor’s Orchids

Nazi Iron Man Buddha?

Maya Mural Miracle

Neutron Beams and Lead Shot

Site of a Forgotten War

Denisovan DNA

Turning Back the Human Clock

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

T

T Bray and Echeverría think they have found the estanque Cieza de León recorded. “We call it the ‘Templo de Agua’—the Water Temple,” Bray says. “You find pools at almost every Inca site, but they’re usually

Bray and Echeverría think they have found the estanque Cieza de León recorded. “We call it the ‘Templo de Agua’—the Water Temple,” Bray says. “You find pools at almost every Inca site, but they’re usually  “I think Huayna Capac built the site, and then Atahualpa remodeled it for his coronation,” says Bray. Every new Inca ruler traditionally founded an estate for his royal lineage and Bray believes that may have been Atahualpa’s intention at Inca-Caranqui. The new floor level would have been part of Atahualpa’s remodeling. It could also have been to correct some kind of functional problem, she admits. Either way, she says, it was probably the last major Inca construction project. In

“I think Huayna Capac built the site, and then Atahualpa remodeled it for his coronation,” says Bray. Every new Inca ruler traditionally founded an estate for his royal lineage and Bray believes that may have been Atahualpa’s intention at Inca-Caranqui. The new floor level would have been part of Atahualpa’s remodeling. It could also have been to correct some kind of functional problem, she admits. Either way, she says, it was probably the last major Inca construction project. In  “It’s really impressive, what the Inca did without iron, steel, or written language,” says Ken Wright, a hydraulic engineer who has studied Inca water control techniques. “They did so much with so little, it’s just miraculous,” he says. The Inca came to power in a period of increasing precipitation, after a drought that lasted roughly from A.D.

“It’s really impressive, what the Inca did without iron, steel, or written language,” says Ken Wright, a hydraulic engineer who has studied Inca water control techniques. “They did so much with so little, it’s just miraculous,” he says. The Inca came to power in a period of increasing precipitation, after a drought that lasted roughly from A.D.  The Inca considered some natural springs to be sacred places of ancestral emergence, mirrored by the water itself coming to the surface, Dean says. The Inca often enhanced these natural sources with fine stonework such as spouts and pools in places such as the

The Inca considered some natural springs to be sacred places of ancestral emergence, mirrored by the water itself coming to the surface, Dean says. The Inca often enhanced these natural sources with fine stonework such as spouts and pools in places such as the

The earliest structures Card and his colleagues have revealed are a series of oval-shaped stone buildings dating to around 3000 B.C. In most cases, only fragments of the buildings have been excavated, with the remainder still buried beneath later structures. However, the fragments suggest that the buildings were divided into different areas by upright slabs arranged in a radial pattern like the spokes on a bicycle wheel. In at least one of these buildings there was a hearth in the center, and in some there were a few sherds of what is known as “Grooved Ware” pottery.

The earliest structures Card and his colleagues have revealed are a series of oval-shaped stone buildings dating to around 3000 B.C. In most cases, only fragments of the buildings have been excavated, with the remainder still buried beneath later structures. However, the fragments suggest that the buildings were divided into different areas by upright slabs arranged in a radial pattern like the spokes on a bicycle wheel. In at least one of these buildings there was a hearth in the center, and in some there were a few sherds of what is known as “Grooved Ware” pottery.