Mosaic Masters

November/December 2012

Mine Yar and Celal Kucuk, a couple who own the Istanbul-based Art Restorasyon, first came to Zeugma on May 5, 2000, as volunteers to help with emergency mosaic removals necessitated by the construction of the Birecik Dam. For the next month and a half they toiled every day, until the site was covered with water. “We were working against nature,” says Yar, recalling not only the rising water, but also the snakes and other animals heading up the hillside to escape the impending flood. “It was a very exciting time,” she adds. During this period, Yar says, at least 3,000 square feet of mosaics, about 15 complete ones in all, were removed from two Roman villas. The mosaics are now on display in the Zeugma Mosaic Museum in nearby Gaziantep. After the initial on-site work was completed, Kucuk and Yar were part of a team of dozens of conservators, archaeologists, art historians, and local mosaic masters gathered in the museum’s impressive restoration laboratory. Work on the mosaics from Zeugma is now finished, mosaics from the region are still being conserved in the laboratory, and Yar and Kucuk continue their preservation efforts on other projects.

But how were the mosaics initially removed from Zeugma more than a decade ago? The team used different techniques depending on the mosaic. For mosaics with a big emblema (central figure) such as the Poseidon—the emblema alone was more than 300 square feet— they used a specially built wooden roller. To begin, the team slipped metal rods under the layer of tesserae (the small square stones from which mosaics are made). This raised the entire mosaic up from the floor. They then placed the roller, which was about nine feet long and almost four feet in diameter, on top of the mosaic and “rolled” it up like a carpet. The other technique the team used was to cut the mosaic into both big and small sections, but Kucuk says this is not the preferred method. “We didn’t want to cut them into pieces because every time you put them back together, you add to the story of the mosaic. You especially don’t want to cut the emblema,” he says. “You also need to be aware of how cutting it up will affect your ability to restore the mosaic later,” he adds.

But how were the mosaics initially removed from Zeugma more than a decade ago? The team used different techniques depending on the mosaic. For mosaics with a big emblema (central figure) such as the Poseidon—the emblema alone was more than 300 square feet— they used a specially built wooden roller. To begin, the team slipped metal rods under the layer of tesserae (the small square stones from which mosaics are made). This raised the entire mosaic up from the floor. They then placed the roller, which was about nine feet long and almost four feet in diameter, on top of the mosaic and “rolled” it up like a carpet. The other technique the team used was to cut the mosaic into both big and small sections, but Kucuk says this is not the preferred method. “We didn’t want to cut them into pieces because every time you put them back together, you add to the story of the mosaic. You especially don’t want to cut the emblema,” he says. “You also need to be aware of how cutting it up will affect your ability to restore the mosaic later,” he adds.

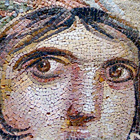

While doing restoration work, Yar noticed that sections of tesserae had been replaced in three mosaics, one featuring the three muses, a second showing the goddess of the earth, Gaea, and a third geometric mosaic that once covered a pool. “Maybe the lady of the house wanted to redecorate,” she says. She also detected other irregularities in a geometric mosaic where stones were used irregularly to fill cracks or holes, indicating that the emblema had been changed, although what the original depicted remains unknown. During the rescue work Kucuk says the team learned about how the mosaics had been made. “We found drawings underneath the mosaics showing the ancient workers where to place the panels,” he explains. “This helped us understand that mosaic panels were not put together inside the house. Instead, they made them in the workplace and then brought the finished mosaic to the home in pieces and placed it, section by section, on the floor.”

|

Main Article:

|

Zeugma After

the Flood

|

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From The Trenches

The Desert and the Dead

Fractals and Pyramids

Off the Grid

Mosaics of Huqoq

Medieval Fashion Statement

The Bog Army

Who Came to America First?

Settling Southeast Asia

Livestock for the Afterlife

Running Guns to Irish Rebels

High Rise of the Dead

Diagnosis of Ancient Illness

Pharaoh’s Port?

Peru’s Mysterious Infant Burials

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement