Features

A Soldier's Story

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Friday, February 08, 2013

UPDATE: In early 2015, the soldier's remains were identified as possibly being those of Friedrich Brandt, a member of the King’s German Legion, made up of German soldiers who fought with the British Army during the Napoleonic Wars.

The battle began mid-morning, Sunday, June 18, 1815. Throughout the day, more than 200,000 soldiers met on a piece of land only 2.5 miles square near the small Belgian town of Waterloo. Blinded by smoke from gunpowder, deafened by cannon blasts, and in constant fear of long-distance gunfire, close-range saber fights, or being trampled in a cavalry charge, the soldiers fought on. By evening, the battleground was completely covered with the wounded, dead, and dying. The Allied forces, led by the Duke of Wellington and the Prussian General von Blücher, had defeated Napoleon’s Grande Armée by the slimmest of margins, signaling the end of the emperor’s reign in France and ushering in a period of prosperity and peace in Europe that would last for nearly half a century. But a battle’s stories are not only those of dethroned monarchs, victorious generals, or territory gained or lost. Sometimes the remains of the men who died on that day tell the richest tales.

Behind the British lines, away from the battlefield, a single soldier lay mortally wounded by a musket ball. Perhaps he dragged himself behind the front line, dropped to the ground to rest, and died not long after. Or maybe he expired before he could be transported to the infirmary, less than 1,000 feet away. He likely died in the early to middle part of the day and was quickly buried by his comrades or by an explosion that churned up the earth and covered his body. Had he died at the end of or after the battle, his corpse would have been recovered by soldiers collecting their dead. But this soldier would have to wait a while longer for someone to tell his story.

Almost two centuries after the soldier’s death, the role of storyteller fell to archaeologist Dominique Bosquet of the Université libre de Bruxelles. He found the soldier while excavating before construction near the battle monument known as the Lion’s Mound. For Bosquet, the discovery was a complete surprise. “I think this is a unique case,” he says. “We excavated 120 trenches in this area, covering more than half an acre, and found almost nothing and no other remains.” In fact, the soldier is not just the only one to have been found in this area—he is the first and only British soldier to have fought and died at Waterloo ever discovered on the site. (Another soldier was supposedly found in the early twentieth century; however, later DNA analysis showed that the remains came from two different people and that that “soldier” was a forgery.) Although the soldier’s head and one of his knees were destroyed by a bulldozer, and some of the bones of his hands and feet were damaged either by a plow—the area has long been a wheat field—or perhaps by a battlefield explosion that tore them away, the skeleton is remarkably intact. Bosquet is able to say that he was between 20 and 29 years old, about five feet three inches tall, with a slender frame.

Almost two centuries after the soldier’s death, the role of storyteller fell to archaeologist Dominique Bosquet of the Université libre de Bruxelles. He found the soldier while excavating before construction near the battle monument known as the Lion’s Mound. For Bosquet, the discovery was a complete surprise. “I think this is a unique case,” he says. “We excavated 120 trenches in this area, covering more than half an acre, and found almost nothing and no other remains.” In fact, the soldier is not just the only one to have been found in this area—he is the first and only British soldier to have fought and died at Waterloo ever discovered on the site. (Another soldier was supposedly found in the early twentieth century; however, later DNA analysis showed that the remains came from two different people and that that “soldier” was a forgery.) Although the soldier’s head and one of his knees were destroyed by a bulldozer, and some of the bones of his hands and feet were damaged either by a plow—the area has long been a wheat field—or perhaps by a battlefield explosion that tore them away, the skeleton is remarkably intact. Bosquet is able to say that he was between 20 and 29 years old, about five feet three inches tall, with a slender frame.

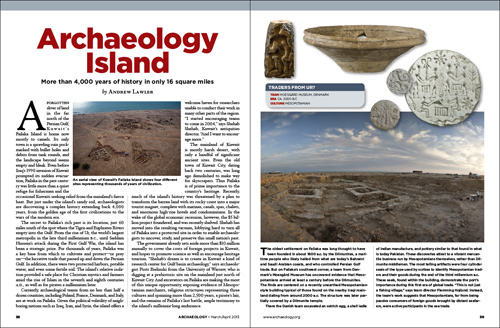

Archaeology Island

By ANDREW LAWLER

Monday, February 11, 2013

A forgotten sliver of land in the far north of the Persian Gulf, Kuwait’s Failaka Island is home now mostly to camels. Its only town is a sprawling ruin pockmarked with bullet holes and debris from tank rounds, and the landscape beyond seems empty and bleak. Even before Iraq’s 1990 invasion of Kuwait prompted its sudden evacuation, Failaka in the past century was little more than a quiet refuge for fishermen and the occasional Kuwaiti seeking relief from the mainland’s fierce heat. But just under the island’s sandy soil, archaeologists are discovering a complex history extending back 4,000 years, from the golden age of the first civilizations to the wars of the modern era.

The secret to Failaka’s rich past is its location, just 60 miles south of the spot where the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers empty into the Gulf. From the rise of Ur, the world’s largest metropolis in the late third millennium B.C., until Saddam Hussein’s attack during the First Gulf War, the island has been a strategic prize. For thousands of years, Failaka was a key base from which to cultivate and protect—or prey on—the lucrative trade that passed up and down the Persian Gulf. In addition, there were two protected harbors, potable water, and even some fertile soil. The island’s relative isolation provided a safe place for Christian mystics and farmers amid the rise of Islam in the seventh and eighth centuries A.D., as well as for pirates a millennium later.

Currently, archaeological teams from no less than half a dozen countries, including Poland, France, Denmark, and Italy, are at work on Failaka. Given the political volatility of neighboring nations such as Iraq, Iran, and Syria, the island offers a welcome haven for researchers unable to conduct their work in many other parts of the region. “I started encouraging teams to come in 2004,” says Shehab Shehab, Kuwait’s antiquities director. “And I want to encourage more.”

The mainland of Kuwait is mostly harsh desert, with only a handful of significant ancient sites. Even the old town of Kuwait City, dating back two centuries, was long ago demolished to make way for skyscrapers. Thus Failaka is of prime importance to the country’s heritage. Recently, much of the island’s history was threatened by a plan to transform the barren land with its rocky coast into a major tourist magnet, complete with marinas, canals, spas, chalets, and enormous high-rise hotels and condominiums. In the wake of the global economic recession, however, the $5 billion project foundered, and was recently shelved. Shehab has moved into the resulting vacuum, lobbying hard to turn all of Failaka into a protected site in order to enable archaeologists to uncover, study, and preserve this small nation’s past.

The government already sets aside more than $10 million annually to cover the costs of foreign projects in Kuwait, and hopes to promote science as well as encourage heritage tourism. “Shehab’s dream is to create in Kuwait a kind of research center for Gulf basin archaeology,” says archaeologist Piotr Bielinski from the University of Warsaw, who is digging at a prehistoric site on the mainland just north of Kuwait City. And excavators on Failaka are making the most of this unique opportunity, exposing evidence of Mesopotamian merchants, religious structures representing three cultures and spanning more than 2,500 years, a pirate’s lair, and the remains of Failaka’s last battle, ample testimony to the island’s millennia-long endurance.

Pirates of the Original Panama Canal

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Monday, February 11, 2013

Like an illuminated skyline at sea, two dozen cargo ships wait along Panama’s Caribbean coast. One after another, they enter Limon Bay and then the Gatun locks, three hydraulic chambers that lift the ships 85 feet above sea level. They exit into Gatun Lake and then the Chagres River. After 28 miles, through a cleaved mountain ridge and under the Pan-American Highway, the ships enter more locks—the Pedro Miguel lock and the two Miraflores locks—that ease the ships back down to sea level in Balboa Harbor, just southwest of Panama City. A trip through the Panama Canal from Atlantic to Pacific takes around nine hours and costs tens of thousands of dollars in tolls.

Long before the completion of the canal in 1914, this narrowest stretch of the isthmus separating the oceans was already used to avoid an 8,000-mile detour around Cape Horn. Ships unloaded cargo at the mouth of the Chagres River, seven miles from the modern canal entrance. Flat-bottomed river barges then moved people and cargo upriver to within 13 miles of Panama City, where donkeys took over on the Camino de Cruces trail. “For four centuries the Chagres has been the bond of union between the two great oceans of the world, the way between the East and West,” wrote C.L.G. Anderson, an early-twentieth-century historian. Until the river became part of the canal it inspired—dammed to form Gatun Lake—it was the original, natural “Panama Canal.”

Beginning in the sixteenth century, the Spanish used this route to supply Panama City and move gold and silver from the city to galleons in the Caribbean. In 1671, famed English privateer Captain Henry Morgan took the largest pirate fleet in history up the river to sack the city and rattle Spain’s control of the Americas. And centuries later, during the California Gold Rush, it was easier for prospectors to take a steamer to Panama, sail up the river, then make their way north in the Pacific than it was to travel overland between America’s coasts. For all the precious metals that have traveled up and down it, the Chagres has been called “the world’s most valuable river.”

Since the first trans-isthmus railroad opened in 1855, the mouth of the Chagres River has been a backwater surrounded by a clotted jungle full of anteaters, toucans, and bellowing howler monkeys. On a promontory above, shaped like the prow of a massive ship, sit the ruins of El Castillo de San Lorenzo el Real de Chagre, or Fort San Lorenzo, which defended the important trade route between 1626 and 1741. It was sacked several times, including by Morgan’s men on their way to Panama City in 1671. Fritz Hanselmann, an underwater archaeologist at Texas State University, is looking for evidence of the privateer’s Panamanian raid—but not in the fort. He’s focused on a string of whitecaps in the sea 200 yards from it, treacherous Lajas Reef, which sank five of Morgan’s ships, including his flagship Satisfaction.

|

Sidebars:

|

|

City of Towers

|

Horseshoe Wreck

|

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Pirates of the Original Panama Canal

Archaeology Island

A Soldier's Story

Letter from Cambodia

From the Trenches

Saving Northern Ireland's Noble Bog

Off the Grid

Mussel Mass in Lake Ontario

Europe's First Carpenters

Medici Mystery

Deconstructing a Zapotec Figurine

Messages from Quarantine

Let Slip the Pigeons of War

The First Spears

Burials and Reburials in Ancient Pakistan

Life (According to Gut Microbes)

Mapping Maya Cornfields

Inside a Painted Tomb

Minoan Mountaintop Manse

A Prehistoric Cocktail Party

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

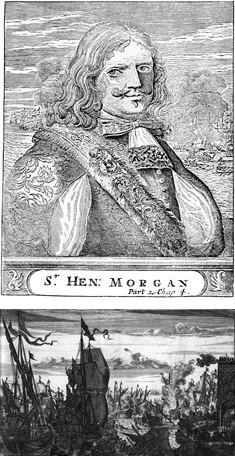

The archaeologist was able to identify the soldier as British not only by his position behind the British lines—in the chaos of the battlefield soldiers could easily find themselves on the wrong side—but by the musket ball still lodged in his rib cage. “According to its weight and diameter, the bullet is definitely French,” says Bosquet. Two flints the soldier carried in his pocket also mark him as a member of Wellington’s forces, as they are dark gray and of dimensions corresponding to the Brown Bess musket, the typical weapon of British troops. By contrast, the flints used to fire the French muskets were light yellow.

The archaeologist was able to identify the soldier as British not only by his position behind the British lines—in the chaos of the battlefield soldiers could easily find themselves on the wrong side—but by the musket ball still lodged in his rib cage. “According to its weight and diameter, the bullet is definitely French,” says Bosquet. Two flints the soldier carried in his pocket also mark him as a member of Wellington’s forces, as they are dark gray and of dimensions corresponding to the Brown Bess musket, the typical weapon of British troops. By contrast, the flints used to fire the French muskets were light yellow. Next to the body the archaeologist found a piece of wood with the initials “C.B.” It is possible that the wood was part of the soldier’s gun, but Bosquet isn’t certain, and admits the initials could be those of another man to whom the object originally belonged. With the regimental insignia that Bosquet hoped to get from the spoon, or that may still come from the buckle, it may be possible to search for a “C.B.” among the British rolls. Without these pieces of evidence, giving the soldier a name is unlikely. But the absence of a name doesn’t make the story any less affecting. “After we uncovered him, I could almost see the guy dying before my eyes,” says Bosquet. “It was very touching and evocative of the cruelty of battle. For me, this was very hard.” Bosquet plans to contact the British embassy and army to ask whether they wish to give the remains a proper burial at Waterloo or have them returned to Britain for interment there. The archaeologist also wants to include the discovery in a new memorial at the site, ensuring that the soldier’s story, once told, will never be forgotten.

Next to the body the archaeologist found a piece of wood with the initials “C.B.” It is possible that the wood was part of the soldier’s gun, but Bosquet isn’t certain, and admits the initials could be those of another man to whom the object originally belonged. With the regimental insignia that Bosquet hoped to get from the spoon, or that may still come from the buckle, it may be possible to search for a “C.B.” among the British rolls. Without these pieces of evidence, giving the soldier a name is unlikely. But the absence of a name doesn’t make the story any less affecting. “After we uncovered him, I could almost see the guy dying before my eyes,” says Bosquet. “It was very touching and evocative of the cruelty of battle. For me, this was very hard.” Bosquet plans to contact the British embassy and army to ask whether they wish to give the remains a proper burial at Waterloo or have them returned to Britain for interment there. The archaeologist also wants to include the discovery in a new memorial at the site, ensuring that the soldier’s story, once told, will never be forgotten.

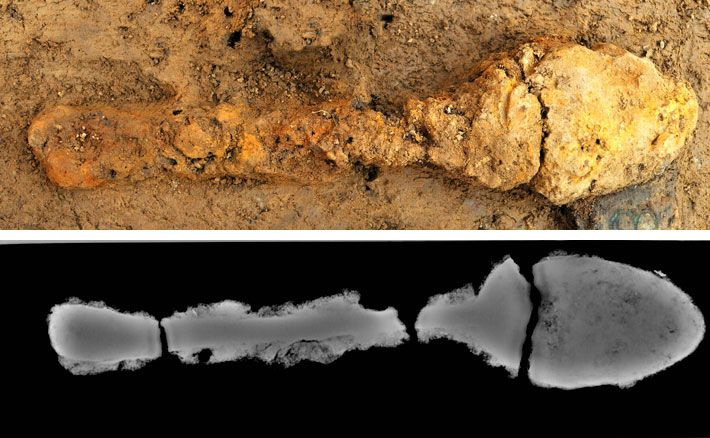

The waters aren’t kind at that time of year, and their dives on Lajas Reef were particularly treacherous. They dropped in on the ocean side of the reef, body-surfed over the top of it, and descended quickly, before the next swell had a chance to toss them around. “You’d just grab onto the nearest rock and hold on,” says Hanselmann, who was then at Indiana University. On the second survey dive, the team found some unmistakable items—encrusted with sea life, but still recognizable—in the rubble at the base of the reef. “There’s no confusing what it is,” says Delgado. “It’s not a sewer pipe. It’s a gun.”

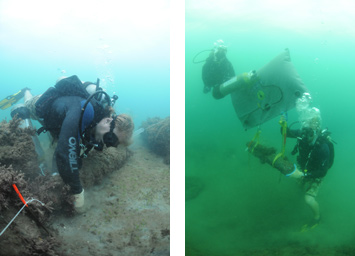

The waters aren’t kind at that time of year, and their dives on Lajas Reef were particularly treacherous. They dropped in on the ocean side of the reef, body-surfed over the top of it, and descended quickly, before the next swell had a chance to toss them around. “You’d just grab onto the nearest rock and hold on,” says Hanselmann, who was then at Indiana University. On the second survey dive, the team found some unmistakable items—encrusted with sea life, but still recognizable—in the rubble at the base of the reef. “There’s no confusing what it is,” says Delgado. “It’s not a sewer pipe. It’s a gun.” Captain Henry Morgan was the premier buccaneer of his age, the man who ransomed Portobello, Panama, and the man who used his own flagship as a decoy and feinted a landward attack to sneak out of heavily defended Maracaibo Harbor in Venezuela. “The name Morgan was really legend in the Caribbean,” says Stephan Talty, author of Empire of Blue Water, about Morgan’s career. His modern image—drawn largely from rum bottles—depicts a dashing, anarchic gadabout, but Morgan was more strategist than swashbuckler. He was also a patriot, from a good military family, who operated as a privateer, a pirate licensed by the British Crown to steal from other countries’ ships and settlements—especially Spain’s. “Morgan was sort of the point of the spear with regard to [England’s handling of] the Spanish Main,” says Talty.

Captain Henry Morgan was the premier buccaneer of his age, the man who ransomed Portobello, Panama, and the man who used his own flagship as a decoy and feinted a landward attack to sneak out of heavily defended Maracaibo Harbor in Venezuela. “The name Morgan was really legend in the Caribbean,” says Stephan Talty, author of Empire of Blue Water, about Morgan’s career. His modern image—drawn largely from rum bottles—depicts a dashing, anarchic gadabout, but Morgan was more strategist than swashbuckler. He was also a patriot, from a good military family, who operated as a privateer, a pirate licensed by the British Crown to steal from other countries’ ships and settlements—especially Spain’s. “Morgan was sort of the point of the spear with regard to [England’s handling of] the Spanish Main,” says Talty.

There are two “Old Panamas” in Panama City: Casco Viejo, the historic district where the town was rebuilt after Morgan’s attack, and Panama Viejo, the ruins of the original. Next to Panama Viejo is the museum of Patronato Panamá Viejo, which includes the conservation lab that is handling the cannons retrieved by Hanselmann and his colleagues. The six cannons rest in water baths in the facility, where researchers hope to learn how they got to be on Lajas Reef. Ruth Brown, formerly of the Royal Armouries in the Tower of London, has several decades of experience studying cannons, and was called on to help identify the Lajas Reef finds. The first telling detail is the size of the guns. They are short, of small caliber. The four smallest are likely to have been deck guns. Pirates and privateers either seized their cannons or purchased them on the secondary market, often resulting in a diverse collection of sizes and makes. No two among them are the same.

There are two “Old Panamas” in Panama City: Casco Viejo, the historic district where the town was rebuilt after Morgan’s attack, and Panama Viejo, the ruins of the original. Next to Panama Viejo is the museum of Patronato Panamá Viejo, which includes the conservation lab that is handling the cannons retrieved by Hanselmann and his colleagues. The six cannons rest in water baths in the facility, where researchers hope to learn how they got to be on Lajas Reef. Ruth Brown, formerly of the Royal Armouries in the Tower of London, has several decades of experience studying cannons, and was called on to help identify the Lajas Reef finds. The first telling detail is the size of the guns. They are short, of small caliber. The four smallest are likely to have been deck guns. Pirates and privateers either seized their cannons or purchased them on the secondary market, often resulting in a diverse collection of sizes and makes. No two among them are the same.