From the Trenches

A Prehistoric Cocktail Party

By NIKHIL SWAMINATHAN

Thursday, February 07, 2013

The 2012 holiday season brought news of several exciting finds from across Europe that make up a veritable cocktail party—including wine, beer, and cheese—of archaeological evidence.

The 2012 holiday season brought news of several exciting finds from across Europe that make up a veritable cocktail party—including wine, beer, and cheese—of archaeological evidence.

In a 2,000-year-old, 100-foot-deep well at the site of Cetamura del Chianti in Tuscany, Italy, archaeologists from Florida State University found 153 grape seeds. The pips date to the period shortly after the Romans claimed the site from the Etruscans. The researchers have identified the grapes as Vitis vinifera, or the wine grape. Because the seeds were not burned, they might carry preserved DNA that could offer insight into the beginnings of viticulture in the region now famous for its bold, fruity reds. “People are going to be interested in the variety of grapes we might be able to identify,” says archaeologist Nancy Thomson de Grummond.

Meanwhile, in western Cyprus, a domed, mud-plaster structure found at the site of Kissonerga-Skalia appears to have been used as a Bronze Age kiln to dry malt for brewing beer. Archaeologist Lindy Crewe of the University of Manchester in England and her team excavated the nearly 4,000-year-old oven, uncovering ashy deposits containing carbonized fig seeds, mortars and other grinding implements, and juglets. They also found sherds of a large clay pot that they believe was a pithos, a vessel in which a fire was lit and used as an indirect heat source within the kiln. Malt, the team hypothesizes, might have been stored in the juglets while they were in the kiln, and then removed to perform the rest of the brewing process.

Finally, new data indicate that sherds from vessels used as sieves, dating back to the sixth millennium B.C. in Poland, have residue of dairy fats on them, suggesting they were used in the earliest known instance of cheese-making. Researchers at the University of Bristol confirmed what Princeton archaeologist Peter Bogucki had suspected for 30 years—that Neolithic farmers in Europe whose settlements were dominated by remains of cattle were dependent on those animals for more than meat.

Taken together, the finds, spanning thousands of years and distant locations, suggest that tastes may not have changed all that much over the millennia.

Minoan Mountaintop Manse

By YANNIS STAVRAKAKIS

Thursday, February 07, 2013

In 1898, archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans visited a small plateau near the town of Ierapetra in southeastern Crete, where he documented in his now-lost diary the remains of a Minoan fort. For almost a century there was no further exploration of the site, called Anatoli, until last summer, when a team from the University of Athens began digging there. Over more than a month, the team unearthed new evidence suggesting that the structure was not, in fact, a defensive fort, but rather a well-preserved two-story villa dating to the New Palace period (1600–1450 B.C.). In addition to walls more than seven feet high, archaeologists also uncovered an impressive stone facade, a room filled with large storage pithoi (ceramic containers), a rock-crystal bead, a bronze ax, and a pillar crypt—a distinctively Minoan ritual structure. Rural villas of this type have been uncovered in Crete before, but they were all situated in the lowlands and plains. Thus the Anatoli villa, at almost 9,000 feet, is only the second to be found at such a high altitude. Excavation director Yiannis Papadatos suggests that it likely functioned as a regional administrative and economic center. Until now, Minoan scholars have focused largely on the island’s lowlands and coastline. In the coming seasons, the team hopes to further explore the role of Minoan mountaintop settlements.

In 1898, archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans visited a small plateau near the town of Ierapetra in southeastern Crete, where he documented in his now-lost diary the remains of a Minoan fort. For almost a century there was no further exploration of the site, called Anatoli, until last summer, when a team from the University of Athens began digging there. Over more than a month, the team unearthed new evidence suggesting that the structure was not, in fact, a defensive fort, but rather a well-preserved two-story villa dating to the New Palace period (1600–1450 B.C.). In addition to walls more than seven feet high, archaeologists also uncovered an impressive stone facade, a room filled with large storage pithoi (ceramic containers), a rock-crystal bead, a bronze ax, and a pillar crypt—a distinctively Minoan ritual structure. Rural villas of this type have been uncovered in Crete before, but they were all situated in the lowlands and plains. Thus the Anatoli villa, at almost 9,000 feet, is only the second to be found at such a high altitude. Excavation director Yiannis Papadatos suggests that it likely functioned as a regional administrative and economic center. Until now, Minoan scholars have focused largely on the island’s lowlands and coastline. In the coming seasons, the team hopes to further explore the role of Minoan mountaintop settlements.

Mapping Maya Cornfields

By KATHERINE SHARPE

Monday, February 11, 2013

Archaeologists have wondered for decades how the ancient Maya, who maintained large cities in hilly territory covered with rain forest and thin soil, were able to produce enough food to support their numbers. “That’s the Maya mystery,” says Richard Terry, a Brigham Young University soil scientist whose work explores the agricultural methods of the civilization. In an excavation at Tikal, Guatemala, once a Maya settlement of some 60,000 people, Terry’s interdisciplinary team is constructing a map of where and when the 115-square-mile site was planted with corn, one of the Maya’s staple crops. Corn leaves distinctive traces in the soil, which the team revealed using mass spectrometry. Understanding how the Maya made use of the land could reveal how they fed their large populations and whether agricultural shortfalls hastened the decline of the civilization.

Archaeologists have wondered for decades how the ancient Maya, who maintained large cities in hilly territory covered with rain forest and thin soil, were able to produce enough food to support their numbers. “That’s the Maya mystery,” says Richard Terry, a Brigham Young University soil scientist whose work explores the agricultural methods of the civilization. In an excavation at Tikal, Guatemala, once a Maya settlement of some 60,000 people, Terry’s interdisciplinary team is constructing a map of where and when the 115-square-mile site was planted with corn, one of the Maya’s staple crops. Corn leaves distinctive traces in the soil, which the team revealed using mass spectrometry. Understanding how the Maya made use of the land could reveal how they fed their large populations and whether agricultural shortfalls hastened the decline of the civilization.

The findings, published in the Soil Science Society of America Journal, show evidence that the Maya planted corn in lowland areas where there was more soil, and that agriculture gradually spread up-slope to thinner soils, where erosion eventually undermined productivity. The next question, says Terry, is whether the Maya developed the capability to cultivate corn in the low-lying wetlands, or bajos, that ring the site. If the Maya did possess a “lost technology” for growing corn in swampy conditions, the Maya crop mystery could constitute a new puzzle, as well as, perhaps, prove useful to modern agriculture.

Inside a Painted Tomb

By ZACH ZORICH

Monday, February 11, 2013

A team of archaeologists from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History has entered a brilliantly painted Maya tomb inside Palenque’s Temple 20, 13 years after it was first discovered, following consultation with dozens of specialists on how best to conserve the find. The tomb is believed to hold the remains of K’uk Bahlam I, the founder of the city’s ruling dynasty, who came to the throne in A.D. 431. In 2011, a camera was lowered through a small hole in the tomb’s ceiling, providing a tantalizing glimpse of the murals (see “A Peek Inside Two Secret Chambers,” September/October 2011). The paintings, which may depict the nine lords of the Maya underworld, will be stabilized and conserved before the tomb is further excavated.

A team of archaeologists from Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History has entered a brilliantly painted Maya tomb inside Palenque’s Temple 20, 13 years after it was first discovered, following consultation with dozens of specialists on how best to conserve the find. The tomb is believed to hold the remains of K’uk Bahlam I, the founder of the city’s ruling dynasty, who came to the throne in A.D. 431. In 2011, a camera was lowered through a small hole in the tomb’s ceiling, providing a tantalizing glimpse of the murals (see “A Peek Inside Two Secret Chambers,” September/October 2011). The paintings, which may depict the nine lords of the Maya underworld, will be stabilized and conserved before the tomb is further excavated.

Life (According to Gut Microbes)

By NIKHIL SWAMINATHAN

Monday, February 11, 2013

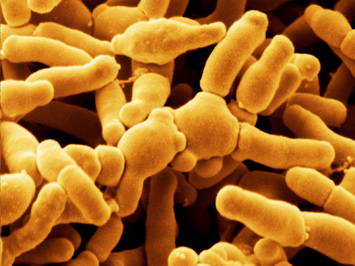

Each of us is home to a vibrant community of gut microbes, the bacteria that live in our digestive systems. Because these bacteria often reflect the diets of their hosts, scientists are examining coprolites—fossilized feces—to learn more about the microbiomes, and lives, of ancient humans.

Each of us is home to a vibrant community of gut microbes, the bacteria that live in our digestive systems. Because these bacteria often reflect the diets of their hosts, scientists are examining coprolites—fossilized feces—to learn more about the microbiomes, and lives, of ancient humans.

For instance, the abundance of the bacteria Bifidobacterium breve—commonly found in the stool of recently breastfed children—in a 1,400-year-old sample taken from La Cueva de los Chiquitos Muertos (“The Cave of Dead Children”) in northern Mexico suggests the coprolite had come from a young child. The sample also contained a large quantity of a bacteria called Prevotella, which indicates a diet heavy in carbohydrates but relatively low in proteins.

Cecil M. Lewis, Jr., a molecular anthropologist at the University of Oklahoma, and his team also found Treponema in both ancient samples and modern rural populations. He thinks this implies that both groups have diets heavy in raw, fibrous foods. The microbe, however, does not appear in the stool of urban or Western populations, which might be attributable to more sanitary living conditions. “As we learn more about how well these microbiome profiles predict aspects of the human condition,” says Lewis, “we can use the information to better understand the past.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Pirates of the Original Panama Canal

Archaeology Island

A Soldier's Story

Letter from Cambodia

From the Trenches

Saving Northern Ireland's Noble Bog

Off the Grid

Mussel Mass in Lake Ontario

Europe's First Carpenters

Medici Mystery

Deconstructing a Zapotec Figurine

Messages from Quarantine

Let Slip the Pigeons of War

The First Spears

Burials and Reburials in Ancient Pakistan

Life (According to Gut Microbes)

Mapping Maya Cornfields

Inside a Painted Tomb

Minoan Mountaintop Manse

A Prehistoric Cocktail Party

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement