From the Trenches

Medici Mystery

By JASON URBANUS

Thursday, February 28, 2013

An investigation into the tomb of the Medici warrior known as Giovanni dalle Bande Nere (“of the Black Bands”), born Lodovico de Medici in 1498, has raised new questions about the famous mercenary’s death. Giovanni earned a fierce reputation early on in life; he was reportedly exiled from Florence at the age of 12 for committing murder. However, his warlike character allowed him to excel as a prominent military captain under the early-sixteenth-century Medici popes, Leo X and Clement VII. He acquired the nickname “dalle Bande Nere” after adding black stripes to his insignia to mourn the death of Pope Leo X in 1521.

An investigation into the tomb of the Medici warrior known as Giovanni dalle Bande Nere (“of the Black Bands”), born Lodovico de Medici in 1498, has raised new questions about the famous mercenary’s death. Giovanni earned a fierce reputation early on in life; he was reportedly exiled from Florence at the age of 12 for committing murder. However, his warlike character allowed him to excel as a prominent military captain under the early-sixteenth-century Medici popes, Leo X and Clement VII. He acquired the nickname “dalle Bande Nere” after adding black stripes to his insignia to mourn the death of Pope Leo X in 1521.

Contemporary Italian accounts of Giovanni’s death indicate that he was struck by a cannonball in 1526. These sources state that his wounds required the amputation of his right leg above the knee, and that he died shortly thereafter, possibly from gangrene resulting from surgery. The Renaissance warrior’s remains have recently been exhumed from the Medici Chapels in Florence. Surprisingly, the bones show that the traditional accounts of his death may not be entirely accurate. Only the lower leg and foot were removed, and the femur was intact. Currently the skeleton is being studied by a team at the University of Pisa led by paleopathologist Gino Fornaciari. “We have already learned that he was a very vigorous man, about 5 foot 8 inches tall, and with evidence on his bones that since adolescence, he carried extremely heavy armor and was often mounted on a horse,” says Fornaciari. “With further study we hope to clarify how Giovanni was wounded and the type of surgical intervention that took place, as well as reconstruct more details about the lives of the Medicis.”

Europe's First Carpenters

By ANDREW CURRY

Thursday, February 28, 2013

Researchers in Germany have discovered four wells more than 7,000 years old. The wells, all underground constructions of hewn oak, are evidence that Neolithic inhabitants of central Europe were accomplished carpenters, capable of felling and working trees three feet thick into planks, then carefully fitting them together. One of the wells, found near the town of Altscherbitz, was removed from water-logged soil in a single 70-ton block and transported to Dresden, where archaeologists “excavated” it in a lab.

Researchers in Germany have discovered four wells more than 7,000 years old. The wells, all underground constructions of hewn oak, are evidence that Neolithic inhabitants of central Europe were accomplished carpenters, capable of felling and working trees three feet thick into planks, then carefully fitting them together. One of the wells, found near the town of Altscherbitz, was removed from water-logged soil in a single 70-ton block and transported to Dresden, where archaeologists “excavated” it in a lab.

There, analysis revealed that the ancient well-builders constructed tusk mortise and tenon joints, a technique that uses a fitted wedge to lock the pieces in place, in the base frame, with the rest constructed in “log cabin” style. “We know the Romans could do it, but that they were in use 5,000 years earlier really came as a surprise,” says Rengert Elburg, an archaeologist at the Saxon Archaeological Heritage Office in Dresden.

The 151 pieces of wood recovered from the wells are also an invaluable source of data for dendrochronologists, who compare tree rings to date artifacts and learn more about past climate conditions. Tree rings suggest the Altscherbitz well was in use for less than a decade before it was deliberately filled with 26 intact pots, thousands of pot fragments, and organic materials including early grains such as emmer and einkorn, strawberries, hazelnuts, and black henbane, a powerful hallucinogen. According to Elburg, the discovery of the pots was particularly surprising. “We don’t normally find intact pots from the Neolithic,” says Elburg. “If you find 26 complete ones, you know it was a ritual deposition. Perhaps it was a well for ritual water or special drinking.”

Off the Grid

By MALIN GRUNBERG BANYASZ

Thursday, February 28, 2013

Even as the flame cauldron from the London 2012 Olympic Games cools, excitement is building for the 2016 Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Much as in London (“London 2012,” July/August 2012), construction and beautification projects around Rio are revealing the city’s past. Experts were aware of the historical significance of the run-down port near the center of town, so when redevelopment of the site began, so did an archaeological project. Excavations uncovered Empress Wharf (Cais da Imperatriz), so named to commemorate the arrival of Princess Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies to marry Emperor Dom Pedro II in 1843. Beneath it was another site, Valongo Wharf (Cais do Valongo). Built in 1811, it was the disembark-ation point for at least 500,000 enslaved Africans after their journey across the Middle Passage. In total, some four million Africans were shipped to Brazil between 1550 and 1888. Head archaeologist Tania Andrade Lima, of the Museu Nacional/Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, says that Valongo represents a crucial part of the city’s history that had long been erased or concealed.

Even as the flame cauldron from the London 2012 Olympic Games cools, excitement is building for the 2016 Games in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Much as in London (“London 2012,” July/August 2012), construction and beautification projects around Rio are revealing the city’s past. Experts were aware of the historical significance of the run-down port near the center of town, so when redevelopment of the site began, so did an archaeological project. Excavations uncovered Empress Wharf (Cais da Imperatriz), so named to commemorate the arrival of Princess Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies to marry Emperor Dom Pedro II in 1843. Beneath it was another site, Valongo Wharf (Cais do Valongo). Built in 1811, it was the disembark-ation point for at least 500,000 enslaved Africans after their journey across the Middle Passage. In total, some four million Africans were shipped to Brazil between 1550 and 1888. Head archaeologist Tania Andrade Lima, of the Museu Nacional/Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, says that Valongo represents a crucial part of the city’s history that had long been erased or concealed.

The site

The site

Valongo was a slave mercantile complex that included, in addition to the wharf, warehouses, markets, a quarantine station, and a cemetery. The excavation focused on pavements and two portions of the site where waste from both the upper classes and slaves accumulated: a natural rainwater drainage area adjacent to the wharf and the once-submerged area in front of the wharf. Tens of thousands of objects were unearthed, many of which were either taken from slaves, or lost or hidden by them. The finds include delicate bracelets, rings woven from vegetable fiber, charms, lumps of amethyst and stones used in African worship, and cowrie shells, then common currency in Africa. In 1843, Valongo and its brutal history were paved over for the arrival of the princess. Now, the city plans to restore that history. A new square displays the exposed remains of the Valongo Wharf and the Empress Wharf as an open-air museum dedicated to an examination of slavery and the African diaspora. The objective of this urban archaeology was to rescue the wharf from oblivion, says Lima, and to celebrate the ways that Africans have enriched Brazilian culture.

While you’re there

Visitors to Rio are sure to find beautiful beaches and wonderful food. A cable car ride up Sugar Loaf Mountain provides panoramic views of the city. The statue of Christ the Redeemer on the Corcovado is one of the wonders of the world, and the city is full of historic churches and museums.

Mussel Mass in Lake Ontario

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Thursday, February 28, 2013

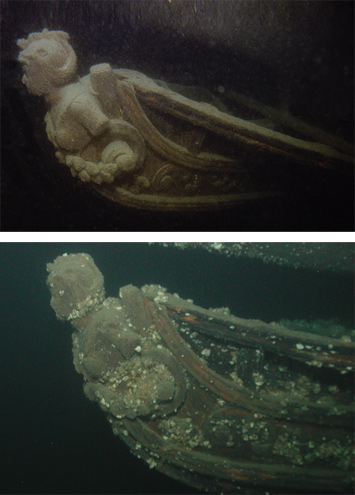

For the last 25 years, invaders have staked an ever-more-alarming claim to the Great Lakes. Zebra and quagga mussels, small molluscs native to eastern Europe, are a serious problem in bodies of freshwater throughout the Midwest. They have colonized and blocked water pipes, and can lead to the breakdown of dock pilings and even steel and concrete. The ongoing invasion has underwater archaeologists concerned about the fate of the lakes’ many historic wrecks. This concern led Parks Canada and the city of Hamilton, Ontario, to begin a new effort to examine the wrecks of Hamilton and Scourge, two merchant ships that were pressed into military service in the War of 1812 and sank in a sudden squall in 1813. Recent surveys using sonar and remotely operated vehicles have revealed significant infestation of the well-preserved wrecks. The quagga mussels present a long-term preservation concern, and they also conceal the wrecks (even though, ironically, they tend to make the water clearer), making the sites increasingly difficult to study and assess.

For the last 25 years, invaders have staked an ever-more-alarming claim to the Great Lakes. Zebra and quagga mussels, small molluscs native to eastern Europe, are a serious problem in bodies of freshwater throughout the Midwest. They have colonized and blocked water pipes, and can lead to the breakdown of dock pilings and even steel and concrete. The ongoing invasion has underwater archaeologists concerned about the fate of the lakes’ many historic wrecks. This concern led Parks Canada and the city of Hamilton, Ontario, to begin a new effort to examine the wrecks of Hamilton and Scourge, two merchant ships that were pressed into military service in the War of 1812 and sank in a sudden squall in 1813. Recent surveys using sonar and remotely operated vehicles have revealed significant infestation of the well-preserved wrecks. The quagga mussels present a long-term preservation concern, and they also conceal the wrecks (even though, ironically, they tend to make the water clearer), making the sites increasingly difficult to study and assess.

Saving Northern Ireland's Noble Bog

By ERIC A. POWELL

Thursday, February 28, 2013

Digital activism carried out by a group of local archaeologists in Northern Ireland has led to the excavation of a significant site that would otherwise have been overlooked. In addition, the campaign has spurred an investigation into cultural heritage management practices and archaeological protocols in the region.

One of the best-preserved rural medieval settlements in the British Isles, the site, in Drumclay, was uncovered by archaeologists excavating a bog in the path of road construction. Working for the Northern Ireland Environment Agency, archaeologist Nora Bermingham and her team have shown that from the eighth to sixteenth centuries, the bog was a lake where generations of a noble Gaelic clan maintained an artificial island that measured some 260 feet across. Known as crannogs, such man-made islands were constructed by medieval elites throughout Scotland and Ireland for both defensive purposes and to broadcast a family’s high status. Few have been excavated since the 1930s, and none on the massive scale of the Drumclay site.

Previously excavated crannogs held up to five dwellings each, but so far Bermingham’s team has discovered the remains of more than 30 wooden buildings that span the site’s 800-year history. The family associated with it probably maintained five structures on Drumclay crannog at any one time, give or take, and about 30 people would have lived there. Though the crannog was marked on nineteenth-century maps and archaeologists scouting the proposed road route noted its presence, little was done to study or preserve it until last summer, when a limited six-week dig was organized by the Northern Ireland Roads Service. Concerned that authorities were preparing to shut down excavation of a major site before it had been properly studied, archaeologists on the project leaked information and photos from the dig to former medieval archaeologist Robert Chappelle, who posted them to his blog. Local archaeologists then launched a robust social media campaign to encourage the government to allocate more time and resources to the excavations. In July, Minister of the Environment Alex Attwood visited the dig and declared a “no go” zone around the crannog, limiting construction activity at the site. He later extended the excavation’s deadline until December, and then again until March 2013, giving Bermingham and her team time to explore the settlement fully.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

Pirates of the Original Panama Canal

Archaeology Island

A Soldier's Story

Letter from Cambodia

From the Trenches

Saving Northern Ireland's Noble Bog

Off the Grid

Mussel Mass in Lake Ontario

Europe's First Carpenters

Medici Mystery

Deconstructing a Zapotec Figurine

Messages from Quarantine

Let Slip the Pigeons of War

The First Spears

Burials and Reburials in Ancient Pakistan

Life (According to Gut Microbes)

Mapping Maya Cornfields

Inside a Painted Tomb

Minoan Mountaintop Manse

A Prehistoric Cocktail Party

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

Bermingham will use copious environmental samples to reconstruct what conditions were like for the families that lived on the crannog. “We know their houses were damp and dank places,” she says, “but we want to get much more detail, to the level of what parasites were bugging them and what the microenvironmental differences were between the different buildings.” Amid the remains, the team has recovered more than 4,000 objects, including leather shoes, gaming pieces, delicate combs, and Bermingham’s favorite artifact: a wooden cheese mold with a cross incised on the bottom. “The quantity of material means we’re able to seriously review how early medieval Irish society functioned,” says Bermingham. “We can also compare our archaeological evidence with documentary sources such as the Annals of Ulster and the Lives of Irish Saints.” Some of the same medieval records could eventually give researchers the family name of the Drumclay crannog clan.

Bermingham will use copious environmental samples to reconstruct what conditions were like for the families that lived on the crannog. “We know their houses were damp and dank places,” she says, “but we want to get much more detail, to the level of what parasites were bugging them and what the microenvironmental differences were between the different buildings.” Amid the remains, the team has recovered more than 4,000 objects, including leather shoes, gaming pieces, delicate combs, and Bermingham’s favorite artifact: a wooden cheese mold with a cross incised on the bottom. “The quantity of material means we’re able to seriously review how early medieval Irish society functioned,” says Bermingham. “We can also compare our archaeological evidence with documentary sources such as the Annals of Ulster and the Lives of Irish Saints.” Some of the same medieval records could eventually give researchers the family name of the Drumclay crannog clan.