Online Exclusives

History's 10 Greatest Wrecks...

By JAMES P. DELGADO

Monday, March 11, 2013

The first scientific archaeological excavation of a shipwreck took place just over 50 years ago. Since then, thousands of wrecks have been discovered, each with an important story to tell. Choosing 10 from among them to represent the endeavor of nautical archaeology is a difficult—and subjective—task. But each offers a profile of an age and a window into the lives of its people, as well as evidence of just how clever and innovative our ancestors were as they took to the seas. Through these stories, we also see why archaeologists continue to devote themselves, despite danger and difficulty, to the examination and excavation of wrecks, wherever they might be discovered. From the rudimentary dive equipment of the earliest excavations to the sophisticated remote-sensing and remotely operated technology of today, archaeologists have shown that no site is beyond the reach of our inquiry into the past.

The first scientific archaeological excavation of a shipwreck took place just over 50 years ago. Since then, thousands of wrecks have been discovered, each with an important story to tell. Choosing 10 from among them to represent the endeavor of nautical archaeology is a difficult—and subjective—task. But each offers a profile of an age and a window into the lives of its people, as well as evidence of just how clever and innovative our ancestors were as they took to the seas. Through these stories, we also see why archaeologists continue to devote themselves, despite danger and difficulty, to the examination and excavation of wrecks, wherever they might be discovered. From the rudimentary dive equipment of the earliest excavations to the sophisticated remote-sensing and remotely operated technology of today, archaeologists have shown that no site is beyond the reach of our inquiry into the past.

To read about five sites that archaeologists still seek, pick up a copy of ARCHAEOLOGY's special collector's edition, SHIPWRECKS, on your newsstand—or order it online today.

To read about five sites that archaeologists still seek, pick up a copy of ARCHAEOLOGY's special collector's edition, SHIPWRECKS, on your newsstand—or order it online today.

National Museum, Baghdad: 10 Years Later

By ANDREW LAWLER

Thursday, April 11, 2013

The round hole made by an artillery shell was visible long before we pulled up next to the National Museum in Baghdad in early May of 2003. The puncture, just below a frieze of a king in a chariot, was in the replica of a Babylon gate next to the exhibit halls. An American tank sat in the archway. Though I had seen images of the destruction that took place a month before, the sight was startling.

The round hole made by an artillery shell was visible long before we pulled up next to the National Museum in Baghdad in early May of 2003. The puncture, just below a frieze of a king in a chariot, was in the replica of a Babylon gate next to the exhibit halls. An American tank sat in the archway. Though I had seen images of the destruction that took place a month before, the sight was startling.

Inside it was worse. The administrative area was in shambles. Filing cabinets were turned over, and papers dating back to the museum’s founding by British archaeologist Gertrude Bell in the 1920s, were strewn about. Small fires had destroyed some offices. In the display area, angry mobs had shattered the cases and smashed 2,000-year-old statues. The primary storage facility had been breached, and some 15,000 objects—no one knows exactly how many—were gone. Among the missing pieces were thousands of tiny cylinder seals, as well as several iconic artifacts such as the Lady of Warka, a stone head of a woman found at Uruk, which is considered the world’s oldest city.

Had museum officials not hidden 8,366 of the most valuable artifacts in a safe place known only to them, this event might have been a catastrophe for cultural heritage in Iraq. For a while, no one knew for certain how much damage had been done; I was with a team of U.S. archaeologists who arrived to assess the situation. Most of the museum’s estimated 170,000 artifacts were eventually found to be safe. The rampage had earned front-page headlines across the world. It was entirely preventable.

Some 2,500 years earlier, the Persian king Cyrus the Great was able to storm nearby Babylon, then the world’s largest city, but texts from the time relate that there was no chaos or looting. However, in 2003, American troops failed to secure what was second on their own list, after the Central Bank, of important places to protect in the modern Iraqi capital. Archaeologists had visited the Pentagon prior to the invasion to provide military officials with detailed coordinates of all major Iraqi cultural heritage sites.

The looting of the museum was over less than 48 hours after it began on April 10, 2003. But it was only the start of a decade of disaster for Iraq’s cultural heritage, a heritage that includes the world’s first cities, empires, and writing system. More than ancient vases and display cases were affected. The invasion began a grim era of sectarian violence and lawlessness in the very land that developed the state, legal codes, and recorded history itself. That era continues. “These are still very tough days,” says Abdul-Amir Hamdani, an Iraqi archaeologist who today is working on a doctorate at the State University of New York (SUNY) at Stony Brook. I first met Hamdani in May 2003 on the sidewalk outside U.S. military headquarters in the southern city of Nasiriya, where he was desperately attempting to get help to stop the vandals poaching ancient sites. “There is still nothing protecting many sites from looting and destruction.”

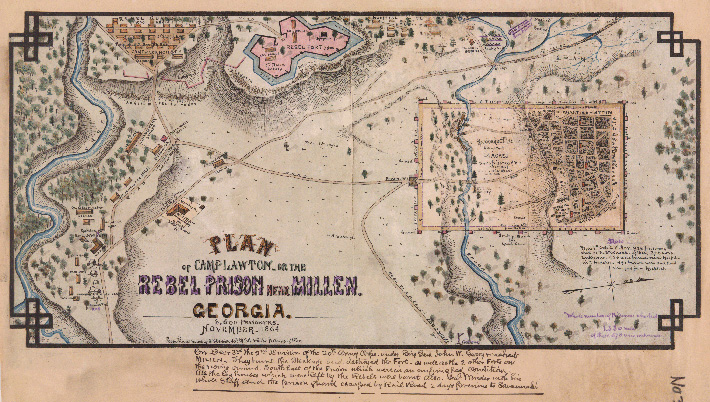

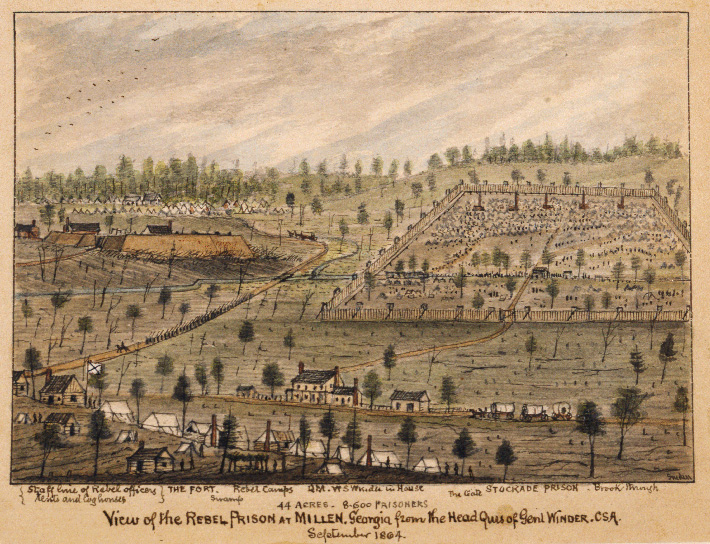

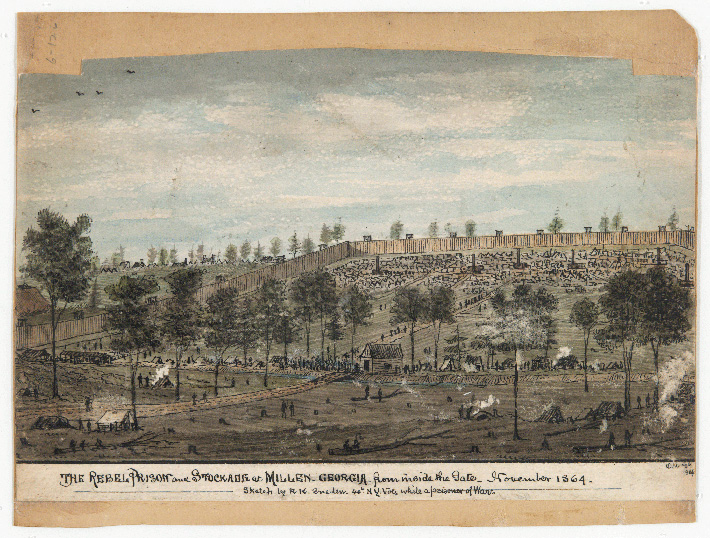

A Civil War POW Camp in Watercolor

By NIKHIL SWAMINATHAN

Sunday, November 10, 2013

On November 27, 1863, Union Private Robert Knox Sneden was captured by soldiers under the command of Confederate leader John Singleton Mosby at Brandy Station, Virginia. It would mark the beginning of a year of captivity for the topographical engineer-turned-mapmaker. He would spend six-and-a-half months at the infamous Andersonville prison in southwest Georgia, a site that would come to symbolize the brutal suffering of the Civil War.

Almost a year after his capture, Sneden was paroled and left under the supervision of Isaiah White, a physician serving Camp Lawton, a newly built POW camp in east Georgia where Sneden had been transferred two months earlier. During his short stint there, Sneden produced several drawings of the prison and its surrounding environs. He would later turn these into watercolors once he returned to New York after the war. “In exchange for promising not to escape, Sneden worked as a clerk for an army surgeon at Camp Lawton," says Andrew Talkov, head of program development at the Virginia Historical Society, which keeps an archive of 5,000 pages from Sneden's personal memoirs that includes the Camp Lawton paintings. "Because of that position, he had greater liberty to move freely around the camp."

Sneden's paintings offer insights about the construction of the prison, how the prisoners lived within it, and the layout of the Confederate encampment that surrounded it. The artwork helped to orient the archaeologists excavating Camp Lawton nearly 150 years after its brief stint holding prisoners of war. “Sneden’s drawings give us imagery in many cases where imagery doesn’t otherwise exist," says VHS lead curator Dr. William M. S. Rasmussen. "Sneden had an incredible visual memory and he combined it with notes and sketches he made in the field to produce an impressive visual record of life during the Civil War.”

Click on the map to view a larger, scrollable version of Sneden's depiction.

|

Feature:

|

Sidebar:

|

Life on the Inside

|

Camp Lawton's Stockade and Forgotten Population

|

Telling Tales in Proto-Indo-European

By ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, September 17, 2013

By the 19th century, linguists knew that all modern Indo-European languages descended from a single tongue. Called Proto-Indo-European, or PIE, it was spoken by a people who lived from roughly 4500 to 2500 B.C., and left no written texts. The question became, what did PIE sound like? In 1868, German linguist August Schleicher used reconstructed Proto-Indo-European vocabulary to create a fable in order to hear some approximation of PIE. Called “The Sheep and the Horses,” and also known today as Schleicher’s Fable, the short parable tells the story of a shorn sheep who encounters a group of unpleasant horses. As linguists have continued to discover more about PIE (and archaeologists have learned more about the Bronze Age cultures that would have spoken it), this sonic experiment continues and the fable is periodically updated to reflect the most current understanding of how this extinct language would have sounded when it was spoken some 6,000 years ago. Since there is considerable disagreement among scholars about PIE, no single version can be considered definitive. Here, University of Kentucky linguist Andrew Byrd recites his version of the fable, as well as a second story, called "The King and the God," using pronunciation informed by the latest insights into reconstructed PIE.

By the 19th century, linguists knew that all modern Indo-European languages descended from a single tongue. Called Proto-Indo-European, or PIE, it was spoken by a people who lived from roughly 4500 to 2500 B.C., and left no written texts. The question became, what did PIE sound like? In 1868, German linguist August Schleicher used reconstructed Proto-Indo-European vocabulary to create a fable in order to hear some approximation of PIE. Called “The Sheep and the Horses,” and also known today as Schleicher’s Fable, the short parable tells the story of a shorn sheep who encounters a group of unpleasant horses. As linguists have continued to discover more about PIE (and archaeologists have learned more about the Bronze Age cultures that would have spoken it), this sonic experiment continues and the fable is periodically updated to reflect the most current understanding of how this extinct language would have sounded when it was spoken some 6,000 years ago. Since there is considerable disagreement among scholars about PIE, no single version can be considered definitive. Here, University of Kentucky linguist Andrew Byrd recites his version of the fable, as well as a second story, called "The King and the God," using pronunciation informed by the latest insights into reconstructed PIE.

Schleicher originally rendered the fable like this:

Avis akvāsas ka

Avis, jasmin varnā na ā ast, dadarka akvams, tam, vāgham garum vaghantam, tam, bhāram magham, tam, manum āku bharantam. Avis akvabhjams ā vavakat: kard aghnutai mai vidanti manum akvams agantam. Akvāsas ā vavakant: krudhi avai, kard aghnutai vividvant-svas: manus patis varnām avisāms karnauti svabhjam gharmam vastram avibhjams ka varnā na asti. Tat kukruvants avis agram ā bhugat.

Here is the fable in English translation:

The Sheep and the Horses

A sheep that had no wool saw horses, one of them pulling a heavy wagon, one carrying a big load, and one carrying a man quickly. The sheep said to the horses: "My heart pains me, seeing a man driving horses." The horses said: "Listen, sheep, our hearts pain us when we see this: a man, the master, makes the wool of the sheep into a warm garment for himself. And the sheep has no wool." Having heard this, the sheep fled into the plain.

And here is the modern reconstruction recited by Andrew Byrd and rendered here in linguistic notations. It is based on recent work done by linguist H. Craig Melchert, and incorporates a number of sounds unknown at the time Schleicher first created the fable:

H2óu̯is h1éḱu̯ōs-kwe

h2áu̯ei̯ h1i̯osméi̯ h2u̯l̥h1náh2 né h1ést, só h1éḱu̯oms derḱt. só gwr̥hxúm u̯óǵhom u̯eǵhed; só méǵh2m̥ bhórom; só dhǵhémonm̥ h2ṓḱu bhered. h2óu̯is h1ékwoi̯bhi̯os u̯eu̯ked: “dhǵhémonm̥ spéḱi̯oh2 h1éḱu̯oms-kwe h2áǵeti, ḱḗr moi̯ aghnutor”. h1éḱu̯ōs tu u̯eu̯kond: “ḱludhí, h2ou̯ei̯! tód spéḱi̯omes, n̥sméi̯ aghnutór ḱḗr: dhǵhémō, pótis, sē h2áu̯i̯es h2u̯l̥h1náh2 gwhérmom u̯éstrom u̯ept, h2áu̯ibhi̯os tu h2u̯l̥h1náh2 né h1esti. tód ḱeḱluu̯ṓs h2óu̯is h2aǵróm bhuged.

In the 1990s, historical linguists created another short parable in reconstructed PIE. It is loosely based on a passage from the Rigveda, an ancient collection of Sanskrit hymns, in which a king beseeches the god Varuna to grant him a son. Here, Andrew Byrd recites his version of the “The King and the God” in PIE, based on the work of linguists Eric Hamp and the late Subhadra Kumar Sen.

Here is an English translation of the story:

The King and the God

Once there was a king. He was childless. The king wanted a son. He asked his priest: "May a son be born to me!" The priest said to the king: "Pray to the god Werunos." The king approached the god Werunos to pray now to the god. "Hear me, father Werunos!" The god Werunos came down from heaven. "What do you want?" "I want a son." "Let this be so," said the bright god Werunos. The king's lady bore a son.

And here is the story rendered in reconstructed Proto-Indo-European:

H3rḗḱs dei̯u̯ós-kwe

H3rḗḱs h1est; só n̥putlós. H3rḗḱs súhxnum u̯l̥nh1to. Tósi̯o ǵʰéu̯torm̥ prēḱst: "Súhxnus moi̯ ǵn̥h1i̯etōd!" Ǵʰéu̯tōr tom h3rḗǵm̥ u̯eu̯ked: "h1i̯áǵesu̯o dei̯u̯óm U̯érunom". Úpo h3rḗḱs dei̯u̯óm U̯érunom sesole nú dei̯u̯óm h1i̯aǵeto. "ḱludʰí moi, pter U̯erune!" Dei̯u̯ós U̯érunos diu̯és km̥tá gʷah2t. "Kʷíd u̯ēlh1si?" "Súhxnum u̯ēlh1mi." "Tód h1estu", u̯éu̯ked leu̯kós dei̯u̯ós U̯érunos. Nu h3réḱs pótnih2 súhxnum ǵeǵonh1e.

The Sultan’s African Palace

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Monday, December 02, 2013

From the tenth to fifteenth centuries, the East Coast of Africa was home to hundreds of trading towns collectively known as the Swahili Coast. These wealthy, independent Islamic sultanates brought the riches of the African interior, including ivory, gold, and slaves, to a hemisphere-spanning trade network.

Among the richest and most influential of these towns was Kilwa Kisiwani, located on an island off the Tanzanian coast. At Kilwa’s height in the early fourteenth century, its leader, Sultan al-Hasan ibn Sulaiman, constructed a massive palace called Husuni Kubwa. The site, built of jagged blocks of coral called coral rag, is now only accessible from a worn staircase carved out of the cliff leading up from the water. Its ruin includes traditional Swahili elements, such as a stepped greeting court bordered by guest rooms for visiting merchants, and elements borrowed from other Islamic palaces, such as an octagonal swimming pool, grand audience court, and a residence with some 100 rooms. But the sultan had overreached in his ambition: The palace was occupied for only a short time before it was abandoned, unfinished.

|

Feature:

|

Sidebar:

|

Stone Towns of the Swahili Coast

|

Matters of Context

|

Advertisement

Advertisement

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement