Features

The Kings of Kent

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, May 20, 2013

Fifth-century Britain was a tumultuous place, wracked by violence, upheaval, and uncertainty. The Roman Empire was crumbling throughout western Europe as waves of barbarian invaders overran its borders. By A.D. 410, groups of Angles, Saxons, and Jutes began crossing the North Sea from Germany and southern Scandinavia to claim land in Britain that had been abandoned by the Roman army. These tribes succeeded Rome as the dominant power in central and southern Britain, marking the beginning of what we now call the Anglo-Saxon Age, which would last for more than 600 years.

While the story of this period is known to us in broad strokes, in archaeological terms, there remains much to uncover. The early Anglo-Saxon period is a time whose events are often shrouded in fantasy. This fantastical view can be traced to later, Christian writers who described the pagan world of the fifth and sixth centuries as being inhabited by wizards, warriors, demons, and dragons. Legendary tales, passed down, were often the subject of later Old English works of poetry. Perhaps the most famous of all is the epic work Beowulf, whose eponymous hero battles monsters and fire-breathing dragons. But some of the details of early Anglo-Saxon life that have been gleaned piecemeal from texts are now being confirmed by archaeology. Such is the case with the recent surprising discovery of a Saxon royal feasting hall.

For the last six years the Lyminge Archaeological Project has investigated the modern village of Lyminge, Kent, located a short distance from the famous white cliffs of Dover. Researchers from both the University of Reading and the Kent Archaeological Society are documenting Lyminge’s transition from a pagan royal “vill” into a significant Christian monastic center. The settlement encompasses both the pre-Christian and later Christian Anglo-Saxon periods and is proving valuable in understanding the development of early English communities. According to Alexandra Knox, archaeologist and Lyminge Archaeological Project research assistant, the work there is supplying a key piece of the puzzle. “The history of the Christian conversion in Kent,” Knox says, “the historically earliest kingdom to be converted in the Anglo-Saxon period, is integral to our understanding of the creation of medieval and, indeed, modern England.”

The Christian Anglo-Saxon community in Lyminge founded an important “double” monastery—home to both monks and nuns—dating from the seventh to ninth century. The existence of this monastery has been known from at least the middle of the nineteenth century, when Canon Jenkins, a local vicar and amateur archaeologist, discovered the remains of the ancient monastic complex. But apart from these Christian ruins, little was known about Lyminge’s earlier history.

Haunt of the Resurrection Men

By KATE RAVILIOUS

Monday, April 08, 2013

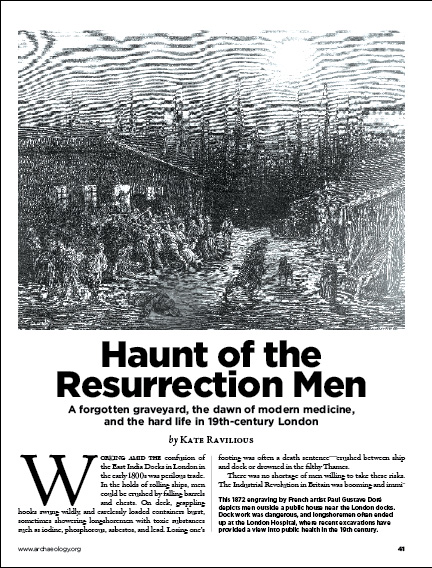

Working amid the confusion of the East India Docks in London in the early 1800s was perilous trade. In the holds of rolling ships, men could be crushed by falling barrels and chests. On deck, grappling hooks swung wildly, and carelessly loaded containers burst, sometimes showering longshoremen with toxic substances such as iodine, phosphorous, asbestos, and lead. Losing one’s footing was often a death sentence—crushed between ship and dock or drowned in the filthy Thames.

There was no shortage of men willing to take these risks. The Industrial Revolution in Britain was booming and immigrants flooded in from Ireland and the continent in search of work. Many ended up on the docks or in the factories of London’s East End. Wages were low and homes scarce—four of every five families lived in filthy single rooms. Open sewers ran down the streets and the air was clogged with soot.

Industrialization took its toll on the community’s health. Their only bulwark against frequent disease outbreaks and horrific injuries was the London Hospital. But among the very sick or seriously hurt, even admission to the hospital did little to improve chances of survival. Infection was rife on the wards and surgery was a brutal business. The standard treatment for a broken bone was amputation, and there were no anesthetics or antiseptics.

In a way, though, for such a bustling, desperate neighborhood, death often represented opportunity. Medical science was undergoing a revolution of its own, and the corpses of the recently deceased were in high demand by surgeons and medical students. Though it was illegal, there was a roaring trade in dead bodies.

Until now, little was known about exactly what nineteenth-century medical professionals did with those cadavers, or how far they were prepared to bend the rules to get them. The recent discovery of a long-forgotten cemetery on the grounds of the London Hospital is illuminating some of these practices and, while some of the details are not for the squeamish, they have much to tell us about the foundation upon which modern medicine is built.

On the Trail of the Mimbres

By JUDE ISABELLA

Monday, April 08, 2013

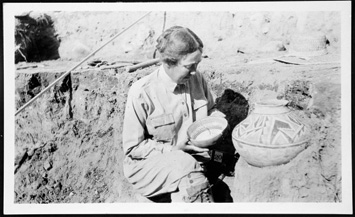

Since first being unearthed in New Mexico in the late nineteenth century, the striking ceramic bowls made a millennium earlier by people living in the Mimbres River Valley of the American Southwest have inspired countless counterfeiters, a clay art festival, a burglary at the University of Minnesota’s anthropology department, and even a line of railroad dinnerware.

Since first being unearthed in New Mexico in the late nineteenth century, the striking ceramic bowls made a millennium earlier by people living in the Mimbres River Valley of the American Southwest have inspired countless counterfeiters, a clay art festival, a burglary at the University of Minnesota’s anthropology department, and even a line of railroad dinnerware.

While their undecorated outsides appear unremarkable in technique and form, their insides are magic, a canvas for haunting depictions of tortoises, fish, jackrabbits, and sometimes humans, as well as intricate geometric designs. The black forms on a white background create an arresting contrast.

For more than a century, beginning in the late tenth century A.D., thousands of these black-on-white bowls were produced, with distinctive designs more spectacular and elaborate than those of any other culture in the Southwest. “It was strikingly unique,” says Steve LeBlanc, an archaeologist at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University, who has studied the pottery makers since the 1970s.The figurative painting on the bowls—sophisticated composite animals and complex scenes and stories—sets Mimbres pottery apart from that of neighboring cultures, where geometric shapes dominated. Then, in 1130, according to the archaeological record, the manufacture of the bowls stopped.

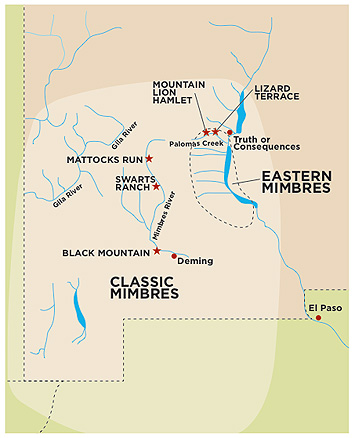

The Mimbres lived in an area that today is nestled in New Mexico’s southwest corner, spilling over the border there with Arizona, and dipping into the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Archaeologists consider Mimbres a subset of the Mogollon culture. Mogollon is one of three major cultures of the ancient American Southwest, along with the Anasazi, also referred to as the Ancestral Pueblo, and the Hohokam. The Ancestral Pueblo are known for large, sophisticated village sites and road systems, such as Pueblo Bonito at Chaco Canyon. The Hohokam engineered complex irrigation canals, unrivaled by other pre-Columbian cultures in North America. Traced to a.d. 200, the Mogollon stretched across the mountainous region near today’s Mexican-American border, living in semiunderground dwellings. Overall, they did not farm intensively. The Mimbres, however, used irrigation methods similar to those of the Hohokam to exploit the fertile floodplains of the Mimbres River in order to produce corn, squash, beans, and other crops.

Advertisement

Also in this Issue:

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

On the Trail of the Mimbres

Haunt of the Resurrection Men

The Kings of Kent

Letter from Turkey

From the Trenches

Albanian Fresco Fiasco

Off The Grid

Visions of Valhalla

Archaic Engineers Worked on a Deadline

Europe's First Farmers

A Pyramid Fit for a Vizier

Second to Whom?

Thracian Treasure Chest

A Major New Venue

A Killer Bacterium Expands Its Legacy

Bad Monks at St. Stephen's

Hail to the Bождь (Chieftain)

Oops! Down the Drain

From Egyptian Blue to Infrared

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

The royal feasting hall in Lyminge remained undisturbed for nearly 1,400 years, just a few inches below the surface of a village green that lies at the center of the modern town, and within view of the monastery site. It is the first of its kind to be discovered in England in more than 30 years. “Excavating large open areas in villages of medieval origin can be an extremely successful strategy in uncovering the evolution of the Saxon village,” explains Knox. “No large building was visible on the geophysical survey, so it was a great surprise to the team to uncover the full floor plan of such a significant structure.”

The royal feasting hall in Lyminge remained undisturbed for nearly 1,400 years, just a few inches below the surface of a village green that lies at the center of the modern town, and within view of the monastery site. It is the first of its kind to be discovered in England in more than 30 years. “Excavating large open areas in villages of medieval origin can be an extremely successful strategy in uncovering the evolution of the Saxon village,” explains Knox. “No large building was visible on the geophysical survey, so it was a great surprise to the team to uncover the full floor plan of such a significant structure.”

The monastery at Lyminge has old and storied connections to the earliest Christian Anglo-Saxons. While the populations of Roman Britain had already converted to Christianity following the conversion of the Roman emperor Constantine in 312, the foreign tribes who invaded the island after the Roman collapse were pagans. St. Augustine of Canterbury was commissioned by Pope Gregory to travel to Britain to reestablish Christianity there and to convert the pagan Saxon communities. Shortly after his pilgrimage in the sixth century, the monastery in Lyminge was founded by Queen Æethelburga, daughter of King Æthelbert of Kent, who, in 597, became the first Anglo-Saxon king to be converted to Christianity.

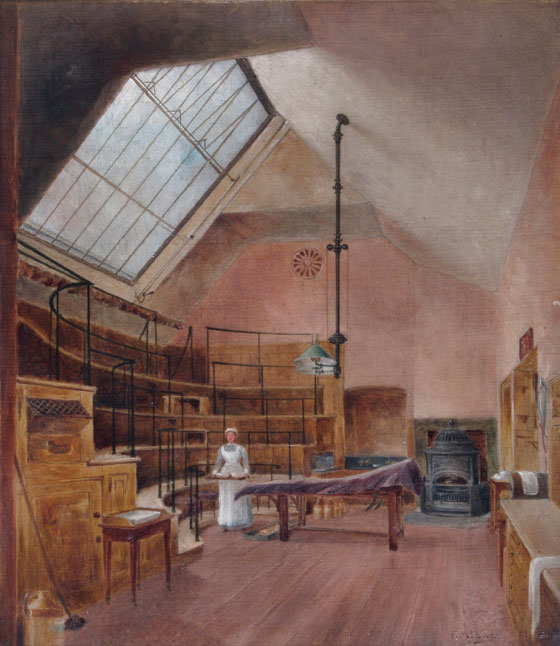

The monastery at Lyminge has old and storied connections to the earliest Christian Anglo-Saxons. While the populations of Roman Britain had already converted to Christianity following the conversion of the Roman emperor Constantine in 312, the foreign tribes who invaded the island after the Roman collapse were pagans. St. Augustine of Canterbury was commissioned by Pope Gregory to travel to Britain to reestablish Christianity there and to convert the pagan Saxon communities. Shortly after his pilgrimage in the sixth century, the monastery in Lyminge was founded by Queen Æethelburga, daughter of King Æthelbert of Kent, who, in 597, became the first Anglo-Saxon king to be converted to Christianity. Today the hospital (which became the Royal London Hospital in 1990) is still going strong. In 2006, an expansion necessitated archaeological excavations in two areas east of the main building. One was a known cemetery used from 1840 onward, while the other turned out to be the long-forgotten burial ground. Covering a key period in medical and social history, the puzzling remains from this cemetery have enabled archaeologists to piece together a surprising, and sometimes unsettling, portrait of the early days of modern medicine.

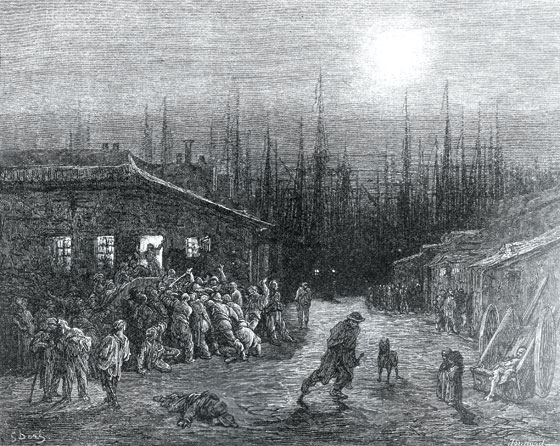

Today the hospital (which became the Royal London Hospital in 1990) is still going strong. In 2006, an expansion necessitated archaeological excavations in two areas east of the main building. One was a known cemetery used from 1840 onward, while the other turned out to be the long-forgotten burial ground. Covering a key period in medical and social history, the puzzling remains from this cemetery have enabled archaeologists to piece together a surprising, and sometimes unsettling, portrait of the early days of modern medicine. Studying the location of cuts on the incomplete skeletons revealed some clear patterns. In particular, many of the bodies had consistent cuts through the vertebrae, to divide the body into three portions: head, torso, and lower body. Some of the cuts demonstrate skill and detailed knowledge of human anatomy, while others are more amateur, with slip marks and multiple attempts at making the same cut. A few of the bones had iron pins inserted into them, or sometimes traces of red dye. And some of the bones were not human but animal, belonging to dogs, cows, and even monkeys.

Studying the location of cuts on the incomplete skeletons revealed some clear patterns. In particular, many of the bodies had consistent cuts through the vertebrae, to divide the body into three portions: head, torso, and lower body. Some of the cuts demonstrate skill and detailed knowledge of human anatomy, while others are more amateur, with slip marks and multiple attempts at making the same cut. A few of the bones had iron pins inserted into them, or sometimes traces of red dye. And some of the bones were not human but animal, belonging to dogs, cows, and even monkeys. The human bones with iron pins in them would have been kept as specimens, and the red staining observed on some fragments, including the remains of a preserved fetus, would have come from red wax pumped through the circulatory system to create models of the arteries and veins, another technique still used today. Other curious finds were some lead casts of an aorta. “We can’t be sure, but perhaps these could be a link to a senior doctor at the London Hospital, Archibald Billing,” says Powers. “He was very interested in trying to diagnose aortic aneurysms and these lead casts may have been his handiwork.”

The human bones with iron pins in them would have been kept as specimens, and the red staining observed on some fragments, including the remains of a preserved fetus, would have come from red wax pumped through the circulatory system to create models of the arteries and veins, another technique still used today. Other curious finds were some lead casts of an aorta. “We can’t be sure, but perhaps these could be a link to a senior doctor at the London Hospital, Archibald Billing,” says Powers. “He was very interested in trying to diagnose aortic aneurysms and these lead casts may have been his handiwork.” The hospital chaplain, Reverend William Valentine, writes in his diary entry for July 2, 1829, about a body-snatching incident: “On Monday morning some wretches had disinterred the body from the ground, but patients saw them from the ward window about 5 o’clock. The fellows left the body in a sack, partially covered, in the grounds, to the horror and disgust of all who saw it.” Ironically, the new finds suggest that many of these stolen skeletons were probably returned to the cemetery eventually—albeit in a very different state from when they were exhumed.

The hospital chaplain, Reverend William Valentine, writes in his diary entry for July 2, 1829, about a body-snatching incident: “On Monday morning some wretches had disinterred the body from the ground, but patients saw them from the ward window about 5 o’clock. The fellows left the body in a sack, partially covered, in the grounds, to the horror and disgust of all who saw it.” Ironically, the new finds suggest that many of these stolen skeletons were probably returned to the cemetery eventually—albeit in a very different state from when they were exhumed. A London Hospital diet sheet from the late eighteenth century shows that hospital food was dire, with no vegetables at all in the meals. “Physicians had to prescribe vegetables specially,” says Evans. The menu shows a stodgy, cereal-based diet with porridge or gruel for breakfast, and broth with bread and cheese later in the day, washed down with beer. A piece of an enema kit found in the graveyard attests to the diet’s effects. Nutrition at home was poor too, as evidenced by the high levels of tooth decay (60 percent of skeletons showed signs of dental disease) and nutritional disorders such as rickets (just over 8 percent of the skeletons had the bowed legs associated with this vitamin D deficiency) and cribra orbitalia (22 percent of the skeletons had small holes in the roofs of their eye sockets, indicative of iron deficiency). Poor diet started early in life, as severe tooth decay in one of the rare examples of a young child’s skeleton demonstrates.

A London Hospital diet sheet from the late eighteenth century shows that hospital food was dire, with no vegetables at all in the meals. “Physicians had to prescribe vegetables specially,” says Evans. The menu shows a stodgy, cereal-based diet with porridge or gruel for breakfast, and broth with bread and cheese later in the day, washed down with beer. A piece of an enema kit found in the graveyard attests to the diet’s effects. Nutrition at home was poor too, as evidenced by the high levels of tooth decay (60 percent of skeletons showed signs of dental disease) and nutritional disorders such as rickets (just over 8 percent of the skeletons had the bowed legs associated with this vitamin D deficiency) and cribra orbitalia (22 percent of the skeletons had small holes in the roofs of their eye sockets, indicative of iron deficiency). Poor diet started early in life, as severe tooth decay in one of the rare examples of a young child’s skeleton demonstrates.

Since then, the prevailing view of researchers was to read the break in the archaeological record as a systemic social collapse—depopulation accompanying the abandonment of a site. Others, such as Margaret Nelson, an archaeologist at Arizona State University (ASU) who began studying the pottery makers as a graduate student in the 1970s, have a different interpretation. For Nelson and her ASU colleague Michelle Hegmon, the sudden cessation of Mimbres pottery production, though abrupt in the archaeological record, doesn’t necessarily point to the end of the Mimbres culture.

Since then, the prevailing view of researchers was to read the break in the archaeological record as a systemic social collapse—depopulation accompanying the abandonment of a site. Others, such as Margaret Nelson, an archaeologist at Arizona State University (ASU) who began studying the pottery makers as a graduate student in the 1970s, have a different interpretation. For Nelson and her ASU colleague Michelle Hegmon, the sudden cessation of Mimbres pottery production, though abrupt in the archaeological record, doesn’t necessarily point to the end of the Mimbres culture. The first decorations on Mimbres pottery—simple geometric shapes in red on brown clay—appear around A.D. 600. The potters developed the black-on-white style, an artistically pleasing contrast found in much Southwest pottery, 150 years later. By about the late 900s, the exceptional design that came to define the Mimbres Classic period took off.

The first decorations on Mimbres pottery—simple geometric shapes in red on brown clay—appear around A.D. 600. The potters developed the black-on-white style, an artistically pleasing contrast found in much Southwest pottery, 150 years later. By about the late 900s, the exceptional design that came to define the Mimbres Classic period took off. LeBlanc notes that researchers have yet to locate the sources of the clay used in Mimbres pottery, although a technique called instrumental neutron activation (bombarding small sherd samples with neutrons to reveal the clay’s chemical composition) reveals that the clay came from a local source. “Clay is heavy stuff,” LeBlanc says. “I would be surprised if they were going farther than a couple of miles to get it.”

LeBlanc notes that researchers have yet to locate the sources of the clay used in Mimbres pottery, although a technique called instrumental neutron activation (bombarding small sherd samples with neutrons to reveal the clay’s chemical composition) reveals that the clay came from a local source. “Clay is heavy stuff,” LeBlanc says. “I would be surprised if they were going farther than a couple of miles to get it.” Nelson says the remodeling of the field houses is akin to having a lake house or cabin in the mountains that initially one only visits a few times per year. “If eventually you left your town and moved into the cabin, you might add a bunch of things that make it a more permanent house for you,” she explains. “That’s what we see happening for those who remained in the region but left their villages at the end of the Classic period.”

Nelson says the remodeling of the field houses is akin to having a lake house or cabin in the mountains that initially one only visits a few times per year. “If eventually you left your town and moved into the cabin, you might add a bunch of things that make it a more permanent house for you,” she explains. “That’s what we see happening for those who remained in the region but left their villages at the end of the Classic period.” The Mimbres people went from creating and using only the iconic bowls that are the signature of their culture to using up to eight different types of pottery that were either imported from anywhere and everywhere or made as copies of the different styles.

The Mimbres people went from creating and using only the iconic bowls that are the signature of their culture to using up to eight different types of pottery that were either imported from anywhere and everywhere or made as copies of the different styles.