From the Trenches

From Egyptian Blue to Infrared

By NIKHIL SWAMINATHAN

Monday, April 08, 2013

Egyptian blue is known as the world’s oldest artificial pigment, first used more than 4,500 years ago, found on wall paintings at Luxor and sculptures recovered from the Parthenon. The hue comes from a compound called calcium copper tetrasilicate. Over the past decade, museum conservators and archaeologists have taken advantage of its properties to spot the presence of Egyptian blue on antiquities: When red light is shone on the pigment, it reflects infrared light, which can be detected via night-vision goggles or cameras.

Egyptian blue is known as the world’s oldest artificial pigment, first used more than 4,500 years ago, found on wall paintings at Luxor and sculptures recovered from the Parthenon. The hue comes from a compound called calcium copper tetrasilicate. Over the past decade, museum conservators and archaeologists have taken advantage of its properties to spot the presence of Egyptian blue on antiquities: When red light is shone on the pigment, it reflects infrared light, which can be detected via night-vision goggles or cameras.

Chemists at the University of Georgia (UGA) have now determined that the luminescent quality of calcium copper tetrasilicate is retained even when the compound is reduced to what are termed “nanosheets,” a thousand times thinner than a human hair. “Even if you have a single layer, the thinnest possible, you still get the effect,” explains UGA’s Tina Salguero. At that scale, she believes, you can start thinking about modern applications.

Salguero says that Egyptian blue’s primary molecule could be incorporated into a dye to improve medical imaging, since the infrared radiation it would reflect can pass through human tissue. The pigment’s luminescent quality could also be effective for developing new types of security ink, typically used to secure currencies and other official documents from forgery. Further, the possibilities for a second act for the long-out-of-use coloring extend to devices such as light-emitting diodes and optical fibers, both of which transmit signals using the relatively long wavelength of infrared light.

The UGA team is now looking at another compound, barium copper tetrasilicate, which was also used as an ancient pigment, in this case by the Chinese.

Oops! Down the Drain

By JASON URBANUS

Monday, April 08, 2013

The next time you lose something valuable down the drain, don’t feel too bad—it’s been happening for 2,000 years. In a recent study, Alissa Whitmore of the University of Iowa examined the broad range of activities that took place in Roman public baths. According to Whitmore, the ancient Romans lost all sorts of precious items, including jewelry, hairpins, and pendants, while bathing. But she also found that they deliberately discarded other things in the baths, such as broken ceramics and glass. Many of the artifacts that have been discovered in bath drains, such as perfume jars, oil flasks, nail cleaners, and tweezers, were related to hygienic behaviors. However, other artifacts indicate that less hygienic activities also took place there. Cups, seashells, animal bones, dice, gaming pieces, and needles suggest that feasting, gambling, and sewing occurred in some baths. The discovery of human teeth and a scalpel also imply that dental and medical procedures may have taken place in some facilities. “The wide variety of finds really drives home that the baths weren’t just for bathing,” says Whitmore, “but a major social center, in which people performed a number of different activities while spending time with friends.

The next time you lose something valuable down the drain, don’t feel too bad—it’s been happening for 2,000 years. In a recent study, Alissa Whitmore of the University of Iowa examined the broad range of activities that took place in Roman public baths. According to Whitmore, the ancient Romans lost all sorts of precious items, including jewelry, hairpins, and pendants, while bathing. But she also found that they deliberately discarded other things in the baths, such as broken ceramics and glass. Many of the artifacts that have been discovered in bath drains, such as perfume jars, oil flasks, nail cleaners, and tweezers, were related to hygienic behaviors. However, other artifacts indicate that less hygienic activities also took place there. Cups, seashells, animal bones, dice, gaming pieces, and needles suggest that feasting, gambling, and sewing occurred in some baths. The discovery of human teeth and a scalpel also imply that dental and medical procedures may have taken place in some facilities. “The wide variety of finds really drives home that the baths weren’t just for bathing,” says Whitmore, “but a major social center, in which people performed a number of different activities while spending time with friends.

Bad Monks at St. Stephen's

By SAMIR S. PATEL

Monday, April 08, 2013

The path to God often comes through self-denial, but sometimes temptation is too great to overcome. St. Stephen’s, a fifth-century monastery in Jerusalem, was home to Byzantine monks who purported to practice an ascetic lifestyle, including the consumption of little more than bread and water (with some fruits and vegetables). Unlike other monasteries of the period, which were often remote desert enclaves, St. Stephen’s was an urban monastery. An isotopic analysis of bone collagen from 54 skeletons at the monastery conducted by Lesley Gregoricka of Ohio State University reveals that 16 of the individuals regularly consumed animal protein, perhaps from eggs, cheese, milk, fish, meat, and perhaps even garum (fermented fish sauce). The city monastery was famously affluent, says Gregoricka, so perhaps higher status monks had access to luxury, taboo, decidedly non-monastic food items.

The path to God often comes through self-denial, but sometimes temptation is too great to overcome. St. Stephen’s, a fifth-century monastery in Jerusalem, was home to Byzantine monks who purported to practice an ascetic lifestyle, including the consumption of little more than bread and water (with some fruits and vegetables). Unlike other monasteries of the period, which were often remote desert enclaves, St. Stephen’s was an urban monastery. An isotopic analysis of bone collagen from 54 skeletons at the monastery conducted by Lesley Gregoricka of Ohio State University reveals that 16 of the individuals regularly consumed animal protein, perhaps from eggs, cheese, milk, fish, meat, and perhaps even garum (fermented fish sauce). The city monastery was famously affluent, says Gregoricka, so perhaps higher status monks had access to luxury, taboo, decidedly non-monastic food items.

Hail to the Bождь (Chieftain)

By ERIC A. POWELL

Monday, April 08, 2013

Russian archaeologists excavating a third-century B.C. necropolis on the slopes of the Central Caucasus Mountains have unearthed a spectacular warrior’s burial. Along with a dozen gold artifacts, including a brooch that holds a small crystal, the warrior went to the afterlife dressed in iron chain mail and armed with two iron swords and a battle-ax. One of the swords measured three feet long and was discovered between the warrior’s legs, its tip pointed toward his pelvis. “The burial goods are exceptionally rich,” says archaeologist Valentina Mordvintseva of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, who helped analyze the unprecedented trove.

Russian archaeologists excavating a third-century B.C. necropolis on the slopes of the Central Caucasus Mountains have unearthed a spectacular warrior’s burial. Along with a dozen gold artifacts, including a brooch that holds a small crystal, the warrior went to the afterlife dressed in iron chain mail and armed with two iron swords and a battle-ax. One of the swords measured three feet long and was discovered between the warrior’s legs, its tip pointed toward his pelvis. “The burial goods are exceptionally rich,” says archaeologist Valentina Mordvintseva of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, who helped analyze the unprecedented trove. “He belonged to the upper class of the society and was possibly a chieftain.” The burial of three horses and a cow nearby indicate that his people held the warrior in unusually high esteem.

“He belonged to the upper class of the society and was possibly a chieftain.” The burial of three horses and a cow nearby indicate that his people held the warrior in unusually high esteem.

A Killer Bacterium Expands Its Legacy

By KATHERINE SHARPE

Monday, April 08, 2013

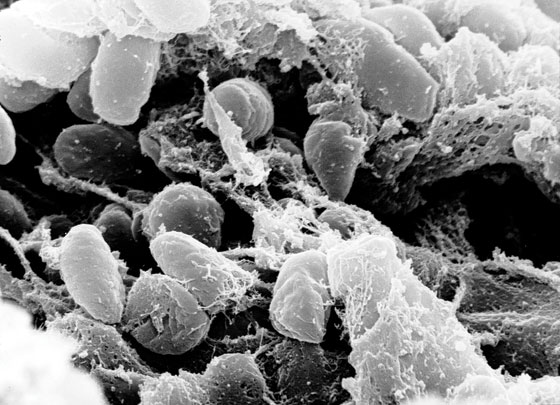

From the sixth through eighth century A.D., a terrifying illness called the Plague of Justinian gripped the Eastern Roman Empire. Like the Black Death pandemic that decimated Europe seven centuries later, this plague often caused death within a matter of days. New work by paleogeneticists at the University of Tübingen in Germany provides empirical evidence for an old historical theory: that the two pandemics were caused by the same pathogen. By comparing the genome of ancient Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for the Black Death, with genetic data from hundreds of less virulent modern strains, the team reconstructed the pathogen’s genetic history, and found evidence suggestive of a significant Y. pestis outbreak corresponding to the Justinian plague. “Our results suggest that Y. pestis may have affected human populations several centuries before the Black Death,” says Kirsten Bos, the study’s lead author. “The Plague of Justinian seems like the best candidate for an earlier pandemic.”

From the sixth through eighth century A.D., a terrifying illness called the Plague of Justinian gripped the Eastern Roman Empire. Like the Black Death pandemic that decimated Europe seven centuries later, this plague often caused death within a matter of days. New work by paleogeneticists at the University of Tübingen in Germany provides empirical evidence for an old historical theory: that the two pandemics were caused by the same pathogen. By comparing the genome of ancient Yersinia pestis, the bacterium responsible for the Black Death, with genetic data from hundreds of less virulent modern strains, the team reconstructed the pathogen’s genetic history, and found evidence suggestive of a significant Y. pestis outbreak corresponding to the Justinian plague. “Our results suggest that Y. pestis may have affected human populations several centuries before the Black Death,” says Kirsten Bos, the study’s lead author. “The Plague of Justinian seems like the best candidate for an earlier pandemic.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

On the Trail of the Mimbres

Haunt of the Resurrection Men

The Kings of Kent

Letter from Turkey

From the Trenches

Albanian Fresco Fiasco

Off The Grid

Visions of Valhalla

Archaic Engineers Worked on a Deadline

Europe's First Farmers

A Pyramid Fit for a Vizier

Second to Whom?

Thracian Treasure Chest

A Major New Venue

A Killer Bacterium Expands Its Legacy

Bad Monks at St. Stephen's

Hail to the Bождь (Chieftain)

Oops! Down the Drain

From Egyptian Blue to Infrared

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement