From the Trenches

A Major New Venue

By KATE RAVILIOUS

Monday, April 08, 2013

Outdoor Roman theaters are common in northwest Europe, but strangely absent from the British Isles. Now, a 2,000-year-old theater has been uncovered, cut into a hillside in southeast England.

Outdoor Roman theaters are common in northwest Europe, but strangely absent from the British Isles. Now, a 2,000-year-old theater has been uncovered, cut into a hillside in southeast England.

Up to 12,000 people could sit in a semicircle of 50 rows of seats. Below was an orchestra pit and a narrow stage, featuring holes that may have allowed the stage to be flooded for aquatic displays such as naval battles. “It was like a spiritual form of the Glastonbury Festival, where people congregated to feast, fair, and communicate with the gods,” says Paul Wilkinson, director of the Kent Archaeological Field School.

The theater overlooks sacred freshwater springs, where inscribed rolls of lead were found which, perhaps, were requests to the gods. Foundations of two temple-like structures, with fragments of a fine, colored mosaic floor, confirm the site’s important sanctuary status. So why aren’t there more Roman theaters in Britain? “I think we just haven’t spotted them yet,” says Wilkinson.

Thracian Treasure Chest

By MATTHEW BRUNWASSER

Monday, April 08, 2013

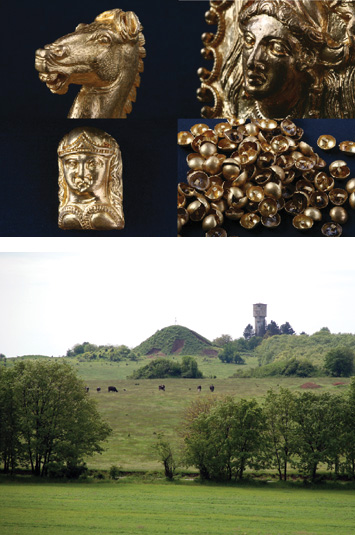

"The Thracians are the most powerful people in the world, except, of course, for the Indians,” wrote the fifth-century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus. In citing the Thracians, he was referring to the group of tribes who inhabited a large part of the Balkans and parts of Western Anatolia—from the Aegean to the Carpathian Mountains, and as far as the Caucasus—from approximately the twelfth century B.C. to the sixth century A.D. Despite their fearsome reputation, relatively little is known about them. Few examples of their writing survive, and what other information we have comes from Greek literary sources and Thracian burial mounds. Many of these mounds have been excavated since the end of the Cold War, when their former lands, Bulgaria and Romania in particular, became accessible to well-trained archaeologists and modern methodology.

"The Thracians are the most powerful people in the world, except, of course, for the Indians,” wrote the fifth-century B.C. Greek historian Herodotus. In citing the Thracians, he was referring to the group of tribes who inhabited a large part of the Balkans and parts of Western Anatolia—from the Aegean to the Carpathian Mountains, and as far as the Caucasus—from approximately the twelfth century B.C. to the sixth century A.D. Despite their fearsome reputation, relatively little is known about them. Few examples of their writing survive, and what other information we have comes from Greek literary sources and Thracian burial mounds. Many of these mounds have been excavated since the end of the Cold War, when their former lands, Bulgaria and Romania in particular, became accessible to well-trained archaeologists and modern methodology.

This past November, archaeologist Diana Gergova of the National Institute of Archaeology at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences entered the burial chamber of an almost 60-foot-tall mound in the Sveshtari necropolis, some 250 miles northeast of the Bulgarian capital of Sofia. There she discovered a wooden chest filled with hundreds of gold artifacts. Gergova believes that the burial belonged to a ruler of the Getae, one of the most powerful of the Thracian tribes, who, around 2,400 years ago, were “at their absolute height, politically, culturally, and militarily.”

According to Gergova, the finely crafted gold treasures from Sveshtari help confirm the ancient writers’ accounts of Thracian culture. The craftsmanship also reveals previously unknown stylistic connections to other tribes in the northern and western regions of the Black Sea, providing evidence for a wide cultural ring across Thracian lands. The site could also provide new insight into the Thracian religion, including their belief in the immortal nature of the human soul, which may have influenced early Christianity, says Gergova. “These finds have given us an incredible amount of information about the burial and post-burial practices of the northern Thracians.”

A Pyramid Fit for a Vizier

By NIKHIL SWAMINATHAN

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Belgian archaeologists recently uncovered a mudbrick structure on a hill at Thebes (modern Luxor) that is actually the base of a pyramid erected for a top minister of 19th Dynasty pharaoh Ramesses II, who ruled Egypt from 1279 to 1213 B.C. Bricks from it are stamped with a rectangular hieroglyphic inscription,“Osiris, the vizier of Upper and Lower Egypt, Khay.” The minister, Khay, who is buried in a tomb beneath the pyramid, can be seen in the structure’s capstone, which pays respect to Re-Horakhty, a combination of the sun god Re and sky god Horus. The pyramid would have measured 40 feet along each side, stood roughly 50 feet tall, and overlooked Ramesses II’s funerary temple.

Belgian archaeologists recently uncovered a mudbrick structure on a hill at Thebes (modern Luxor) that is actually the base of a pyramid erected for a top minister of 19th Dynasty pharaoh Ramesses II, who ruled Egypt from 1279 to 1213 B.C. Bricks from it are stamped with a rectangular hieroglyphic inscription,“Osiris, the vizier of Upper and Lower Egypt, Khay.” The minister, Khay, who is buried in a tomb beneath the pyramid, can be seen in the structure’s capstone, which pays respect to Re-Horakhty, a combination of the sun god Re and sky god Horus. The pyramid would have measured 40 feet along each side, stood roughly 50 feet tall, and overlooked Ramesses II’s funerary temple.

Multiple waves of settlements helped keep the pyramid hidden. Laurent Bavay, an archaeologist at the Université libre de Bruxelles, notes that parts of the monument were used to construct Coptic hermitages atop the site more than 1,300 years ago. Then, in the nineteeenth century, Egyptians arrived at the Theban necropolis to hunt for antiquities they could sell to Europeans. “They literally settled on the tombs to plunder them, systematically,” he explains. The exact location of Khay’s tomb is under one of the remaining local residences, to which the archaeologists do not currently have access.

Second to Whom?

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Over the past three years, archaeologists working at an ancient necropolis outside the city of Suizhou in southern China’s Sichuan Province have excavated 65 tombs. But according to excavation director Huang Fengchun of the Hubei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, tomb 18 in particular is “quite special.” The shape of the tomb resembles the ancient form of the Chinese character “Ya,” which means “second” or “inferior.” The quality of the grave goods found in the tomb, including numerous precious bronze vessels, indicates it likely belonged to a state official of the eastern Zhou Dynasty (770–256 B.C.). But exactly what or whom he was second or inferior to is unknown. Perhaps the answer lies in a 66th tomb.

Over the past three years, archaeologists working at an ancient necropolis outside the city of Suizhou in southern China’s Sichuan Province have excavated 65 tombs. But according to excavation director Huang Fengchun of the Hubei Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, tomb 18 in particular is “quite special.” The shape of the tomb resembles the ancient form of the Chinese character “Ya,” which means “second” or “inferior.” The quality of the grave goods found in the tomb, including numerous precious bronze vessels, indicates it likely belonged to a state official of the eastern Zhou Dynasty (770–256 B.C.). But exactly what or whom he was second or inferior to is unknown. Perhaps the answer lies in a 66th tomb.

Europe's First Farmers

By KATHERINE SHARPE

Tuesday, April 30, 2013

Thousands of years ago, the steep geologic folds of the Danube Gorges region, in present-day Romania and Serbia, were lushly forested and filled with game. The Danube River itself teemed with fish. It was an ideal home for the foragers who had lived there for millennia.

Thousands of years ago, the steep geologic folds of the Danube Gorges region, in present-day Romania and Serbia, were lushly forested and filled with game. The Danube River itself teemed with fish. It was an ideal home for the foragers who had lived there for millennia.

But around 6200 B.C., foreigners began appearing. They came from the south and east, and hailed from farming communities, says anthropologist T. Douglas Price of the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Price recently analyzed strontium isotopes in 153 sets of human teeth from ancient burials in the Gorges. Strontium, which is present in the environment and becomes a permanent part of our tooth enamel in childhood, leaves a distinctive signature that lets scientists pinpoint an individual’s place of origin.

The technique allowed Price and Dušan Borić, of Cardiff University, to document an influx of farmers into the area, including a number of women, who may have married into foraging groups. The work helps settle a decades-old debate about whether farming was brought to Europe by colonizers or diffused from community to community. “In Southeastern Europe,” Price says, “the colonization model is what’s going on.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Features

On the Trail of the Mimbres

Haunt of the Resurrection Men

The Kings of Kent

Letter from Turkey

From the Trenches

Albanian Fresco Fiasco

Off The Grid

Visions of Valhalla

Archaic Engineers Worked on a Deadline

Europe's First Farmers

A Pyramid Fit for a Vizier

Second to Whom?

Thracian Treasure Chest

A Major New Venue

A Killer Bacterium Expands Its Legacy

Bad Monks at St. Stephen's

Hail to the Bождь (Chieftain)

Oops! Down the Drain

From Egyptian Blue to Infrared

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement