Features

Lost Tombs

By JARRETT A. LOBELL and ERIC A. POWELL

Tuesday, July 16, 2013

The improbable discovery last year of Richard III’s skeleton under a parking lot in Leicester, England, is a reminder that while some burials of great historical figures are lost to posterity, careful archaeological sleuthing could still bring them to light. The debate over where to rebury the notorious English king illustrates how important finding the physical remains of these lost rulers can be. And study of Richard III’s remains promises to add to our understanding of both the man himself and the time he lived in. Finding a ruler’s lost tomb may be the most romantic discovery possible in archaeology, but it can also be an opportunity to create a richer picture of ancient life.

The improbable discovery last year of Richard III’s skeleton under a parking lot in Leicester, England, is a reminder that while some burials of great historical figures are lost to posterity, careful archaeological sleuthing could still bring them to light. The debate over where to rebury the notorious English king illustrates how important finding the physical remains of these lost rulers can be. And study of Richard III’s remains promises to add to our understanding of both the man himself and the time he lived in. Finding a ruler’s lost tomb may be the most romantic discovery possible in archaeology, but it can also be an opportunity to create a richer picture of ancient life.

Here are the stories behind the lost final resting places of seven great royal figures, which, if found, could give us exciting insights into our collective past. We’ve also added one burial to the list no archaeologist would ever seek out.

Miniature Pyramids of Sudan

By ERIC A. POWELL

Monday, June 10, 2013

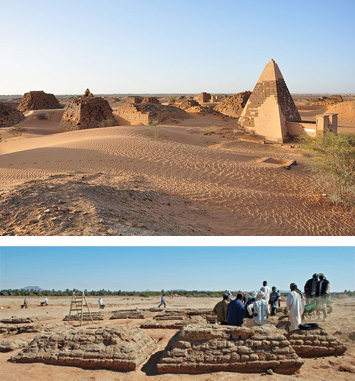

Nearly two thousand years after the Egyptian pharaoh Khufu marshaled armies of workers to build his 480-foot-tall Great Pyramid of Giza, the armies of Nubia (a region that is now in Sudan) invaded and occupied Egypt. It was 730 B.C. and, by then, the Egyptian pharaohs had long since abandoned the practice of erecting massive tombs. It was expensive to do so, and it had nearly bankrupted them. But the pyramids clearly fascinated the Nubian kings. They ruled Egypt during the 25th Dynasty, until they were ejected in 656 B.C., but Egypt’s influence on their own cultural practices was long-lasting. As ongoing archaeological work shows, the inhabitants of Nubia, particularly those in the kingdom of Meroe, found a way to imitate Egypt’s monuments. At the Meroitic royal cemetery, 80 radically downsized pyramids were constructed over the tombs of kings and queens. And now, new excavations at Sedeinga, a necropolis of the same era but 450 miles from Meroe, tell us that the practice of building diminutive pyramids trickled down from royals to the wealthy elite much more extensively than previously believed. Sedeinga contains a dense field of small pyramids, one just 30 inches across. “It is a crazy site,” says Vincent Francigny, a research associate at the American Museum of Natural History and codirector of the excavations at Sedeinga. “I’ve never seen a cemetery like this, with so many small monuments packed so closely together.”

Since a French explorer first described the cemetery at Meroe in the early nineteenth century, archaeologists have identified the remains of more than 220 royal pyramids in Sudan. Excavations show that early in the Meroitic period (ca. 300 B.C.–A.D. 350), pyramids were built exclusively for those of noble blood. “It would have been sacrilege to erect a pyramid for a nonroyal person,” says Francigny. But later in the kingdom’s history the taboo was relaxed somewhat, and a few wealthy people were allowed to erect monuments for themselves. But their pyramids never rivaled the royals’ in size. Royal or not, Nubians would have viewed the pyramids much as the ancient Egyptians did. For the pharaohs, pyramids were symbols of the sun, their massive, steep sides representing the angle of the sun’s rays reaching earth. The people of Meroe elaborated on this theme by adding capstones to their pyramids shaped in classic Egyptian forms, such as birds or lotuses emerging from solar discs.

Since a French explorer first described the cemetery at Meroe in the early nineteenth century, archaeologists have identified the remains of more than 220 royal pyramids in Sudan. Excavations show that early in the Meroitic period (ca. 300 B.C.–A.D. 350), pyramids were built exclusively for those of noble blood. “It would have been sacrilege to erect a pyramid for a nonroyal person,” says Francigny. But later in the kingdom’s history the taboo was relaxed somewhat, and a few wealthy people were allowed to erect monuments for themselves. But their pyramids never rivaled the royals’ in size. Royal or not, Nubians would have viewed the pyramids much as the ancient Egyptians did. For the pharaohs, pyramids were symbols of the sun, their massive, steep sides representing the angle of the sun’s rays reaching earth. The people of Meroe elaborated on this theme by adding capstones to their pyramids shaped in classic Egyptian forms, such as birds or lotuses emerging from solar discs.

In Meroe, two scripts were used that were also inspired by Egypt. But the Meroitic language was considered untranslatable until philologist Claude Rilly, who heads the French Archaeological Mission to Sudan, made some headway beginning in the 1990s. Fewer than 2,000 Meroitic inscriptions are known to exist, many of them funerary inscriptions. To continue his translation effort, Rilly needed more. But he had a problem: Rising waters from dam projects on the Nile over the past decade have inundated most of the recently discovered Meroitic-era cemeteries. The nonroyal cemetery of Sedeinga, which lies on the west bank of the Nile, not far from the Egyptian border, is one of the few already known sites left in Sudan where archaeologists can still excavate graves from the Meroitic period. Rilly and Francigny, an expert in Meroitic funerary monuments, reasoned that uncovering burials at Sedeinga could turn up all-important new inscriptions. This, in large part, is what led them to assemble a team to begin excavating at the site in 2009.

The First Vikings

By ANDREW CURRY

Monday, June 10, 2013

According to historians, the Viking Age began on June 8, A.D. 793, at an island monastery off the coast of northern England. A contemporary chronicle recorded the moment with a brief entry: “The ravages of heathen men miserably destroyed God’s church on Lindisfarne, with plunder and slaughter.” The “heathen men” were Vikings, fierce warriors who sailed from Scandinavia and bore down on their prey in Europe and beyond in sleek, fast-sailing ships. In the centuries that followed, the Vikings’ vessels carried them deep into Russia and as far south as Constantinople, Sicily, and possibly even North Africa. They organized flotillas capable of carrying warriors across vast distances, and terrorized the English, Irish, and French coasts with lightning-fast raids. Exploratory voyages to the west took them all the way to North America.

The Vikings’ explosion across Europe and Asia and into the Americas was the result of the right combination of tools, technology, adventurousness, and ferocity. They came to be known as an unstoppable force capable of raiding and trading on four continents, yet our understanding of what led up to that June day on Lindisfarne is surprisingly shaky. A recent discovery on a remote Baltic island is beginning to change that. Two ships filled with slain warriors uncovered on the Estonian island of Saaremaa may help archaeologists and historians understand how the Vikings’ warships evolved from short-range, rowed craft to sailing ships; where the first warriors came from; and how their battle tactics developed. “We all agree these burials are Scandinavian in origin,” says Marge Konsa, an archaeologist at the University of Tartu. “This is our first taste of the Viking era.”

Between them, the two boats contain the remains of dozens of men. Seven lay haphazardly in the smaller of the two boats, which was found first. Nearby, in the larger vessel, 33 men were buried in a neat pile, stacked like wood, together with their weapons and animals. The site seems to be a hastily arranged mass grave, the final resting place for Scandinavian warriors killed in an ill-fated raid on Saaremaa, or perhaps waylaid on a remote beach by rivals. The archaeologists believe the men died in a battle some time between 700 and 750, perhaps almost as much as a century before the Viking Age officially began. This was an era scholars call the Vendel period, a transitional time not previously known for far-reaching voyages—or even for sails. The two boats themselves bear witness to the tremendous technological transformations in the eighth-century Baltic.

In 2008, workers digging trenches for electrical cables in the tiny island town of Salme uncovered human bones and a variety of odd objects that they unceremoniously piled next to their trench. Local authorities at first assumed the remains belonged to a luckless WWII soldier, until Konsa arrived and recognized a spearhead and carved-bone gaming pieces among the artifacts, clear signs the remains belonged to someone from a much earlier conflict. Together with a small team, Konsa dug a little deeper and soon found traces of a boat’s hull. Nearly all of the craft’s timber had rotted away, leaving behind only discolorations in the soil. But 275 of the iron rivets holding the boat together remained in place, allowing the researchers to reconstruct the outlines of the 38-foot-long craft.

Soon Konsa realized she had found something unique for this place and period. “This isn’t a fishing boat, it’s a war boat,” Konsa says. “It’s quite fast and narrow, and also quite light.” Based on radiocarbon dating of tiny fragments of boat timbers, Konsa estimates the vessel was built between 650 and 700, and perhaps repaired and patched for decades before making its final voyage. It had no sail, and would have been rowed for short stretches along the Baltic coast, or between islands to make the journey from Scandinavia to the seafarers’ hunting grounds farther east. From bones found inside the boat, Konsa pieced together the remains of the seven men, all between the ages of 18 and 45. She also found knives, whetstones, and a bone comb among the remains. The craft was a remarkable find—the first such boat ever recovered in Estonia, complete with the bodies of its slain crew.

Advertisement

DEPARTMENTS

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

From the Trenches

Not Quite Ancient

Off the Grid

Chilling Discovery at Jamestown

Origins of the Maya

Seeds of Europe's Family Tree

France’s Wealthy Warriors

Did the “Father of History” Get It Wrong?

Apollo Returns from the Abyss

Afterlife of a Dignitary

Spain's Lead-Lined Lakes

In Style in the Stone Age

Portals to the Underworld

Roman London Underground

Whale-Barnacle Barbecue

The Human Mosaic

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement

The Salme site may change all that, pushing the first evidence for sailing back a century or more. Though, again, most of the wood had disappeared, by measuring the position of the more than 1,200 nails and rivets and carefully looking at soil where the wood had rotted, Peets concluded that Salme 2 was about 55 feet long and 10 feet wide. The craft had a keel, an element critical to keeping a sailing ship upright in the water. Peets believes clusters of iron and wood near the center of the boat and pieces of cloth recovered from the soil are indications of a mast and sail.

The Salme site may change all that, pushing the first evidence for sailing back a century or more. Though, again, most of the wood had disappeared, by measuring the position of the more than 1,200 nails and rivets and carefully looking at soil where the wood had rotted, Peets concluded that Salme 2 was about 55 feet long and 10 feet wide. The craft had a keel, an element critical to keeping a sailing ship upright in the water. Peets believes clusters of iron and wood near the center of the boat and pieces of cloth recovered from the soil are indications of a mast and sail. Peets, who finished excavating the larger ship, Salme 2, in September 2012, has gathered enough information to sketch out what might have happened. Lured across the sea by booty, to collect tribute from the locals, or to settle a grudge, a mighty raiding party met a formidable foe on this isolated beach. After a struggle, one side’s survivors—there’s no way to tell if they were the winners or the losers—gathered the bodies together and ceremonially destroyed their fallen comrades’ swords by burning, and then bending or breaking them.

Peets, who finished excavating the larger ship, Salme 2, in September 2012, has gathered enough information to sketch out what might have happened. Lured across the sea by booty, to collect tribute from the locals, or to settle a grudge, a mighty raiding party met a formidable foe on this isolated beach. After a struggle, one side’s survivors—there’s no way to tell if they were the winners or the losers—gathered the bodies together and ceremonially destroyed their fallen comrades’ swords by burning, and then bending or breaking them. The Salme finds suggest that the historical view of the Viking Age as a sudden phenomenon needs a radical adjustment. It’s clear from the remains that Scandinavian princes were organizing war parties decades or more before the fateful 793 raid on Lindisfarne: Though the men were interred en masse, the Salme sailing party was far from egalitarian. The weapons paint a picture of warriors led by a rich warlord or chieftain and a handful of well-equipped lieutenants. Even the stack of bodies on Salme 2 was hierarchical. Five men with double-edged swords and elaborately decorated hilts were buried on top. At the bottom, the bodies were buried with simple, single-edged iron blades. “These were some noblemen with their retinue,” Peets says. “The more elaborate swords are clearly connected to people of higher status.” One of the uppermost skeletons even had an elaborately decorated walrus-ivory gaming piece—perhaps the “king”—in his mouth. A jeweled sword hilt, the finest of the 40 blades in the burial, was found nearby. It’s possible the men found in Salme 1 were from the bottom of the social ladder. Konsa thinks they may have been servants or lower-class “support staff,” and buried with less care, and fewer grave goods, far away from the warriors and aristocrats of Salme 2.

The Salme finds suggest that the historical view of the Viking Age as a sudden phenomenon needs a radical adjustment. It’s clear from the remains that Scandinavian princes were organizing war parties decades or more before the fateful 793 raid on Lindisfarne: Though the men were interred en masse, the Salme sailing party was far from egalitarian. The weapons paint a picture of warriors led by a rich warlord or chieftain and a handful of well-equipped lieutenants. Even the stack of bodies on Salme 2 was hierarchical. Five men with double-edged swords and elaborately decorated hilts were buried on top. At the bottom, the bodies were buried with simple, single-edged iron blades. “These were some noblemen with their retinue,” Peets says. “The more elaborate swords are clearly connected to people of higher status.” One of the uppermost skeletons even had an elaborately decorated walrus-ivory gaming piece—perhaps the “king”—in his mouth. A jeweled sword hilt, the finest of the 40 blades in the burial, was found nearby. It’s possible the men found in Salme 1 were from the bottom of the social ladder. Konsa thinks they may have been servants or lower-class “support staff,” and buried with less care, and fewer grave goods, far away from the warriors and aristocrats of Salme 2. Unlike many battlefield graves, and different from the treatment of the seven men found in the first ship, the Salme 2 bodies seem to have been laid to rest with some thought to the afterlife. The man with the severed arm was found with the rest of his limb carefully arranged in its proper place. Allmae’s analysis shows that this would have been an intimidating crew, especially in eighth-century Europe. The average height was 5’10”, and several of the men might have been well over six feet tall. Some of the bones bear signs of old wounds, suggesting these were veterans of more than one scrap. Based on the style of the swords, arrowheads, and other weapons, in addition to the objects found in the graves and especially the boats themselves, Peets and Konsa are already certain that the men were from Scandinavia. “These were very typical swords for Scandinavian warriors,” Peets says. More clues may come from the chemical composition of the bones. Allmae plans to use a technique called isotopic analysis that matches chemical signatures in the bones to trace elements in water to help pin down where the men might have grown up.

Unlike many battlefield graves, and different from the treatment of the seven men found in the first ship, the Salme 2 bodies seem to have been laid to rest with some thought to the afterlife. The man with the severed arm was found with the rest of his limb carefully arranged in its proper place. Allmae’s analysis shows that this would have been an intimidating crew, especially in eighth-century Europe. The average height was 5’10”, and several of the men might have been well over six feet tall. Some of the bones bear signs of old wounds, suggesting these were veterans of more than one scrap. Based on the style of the swords, arrowheads, and other weapons, in addition to the objects found in the graves and especially the boats themselves, Peets and Konsa are already certain that the men were from Scandinavia. “These were very typical swords for Scandinavian warriors,” Peets says. More clues may come from the chemical composition of the bones. Allmae plans to use a technique called isotopic analysis that matches chemical signatures in the bones to trace elements in water to help pin down where the men might have grown up.