Latest News

-

Sanjurjo-Sánchez et al. 2025, Land

Sanjurjo-Sánchez et al. 2025, Land -

University of Bologna

University of Bologna -

Johan Ling

Johan Ling -

Chicama Archaeological Program

Chicama Archaeological Program

-

News March 4, 2026

DNA Study Offers Clues to Contact Between Modern Humans and Neanderthals

Read Article

-

-

News March 3, 2026

Bone Analysis Reveals 3,000 Years of Diet Changes in Prehistoric Poland

Read Article

-

-

-

-

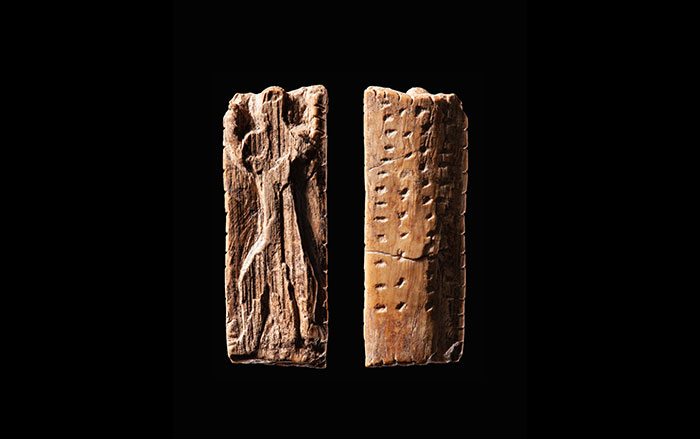

© Landesmuseum Württemberg/Hendrik Zwietasch, CC BY 4.0

© Landesmuseum Württemberg/Hendrik Zwietasch, CC BY 4.0 -

-

News February 27, 2026

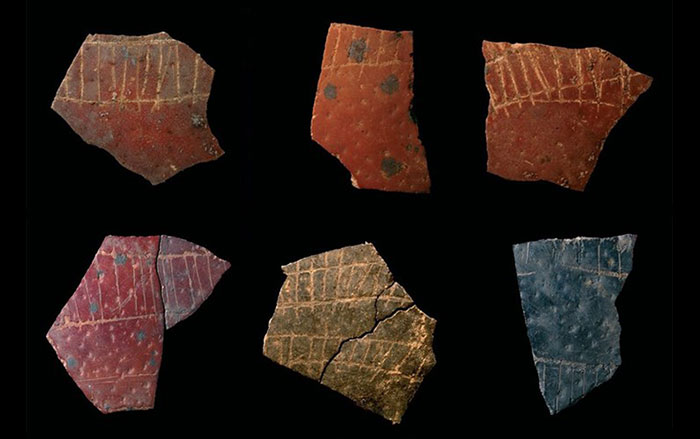

Study Pushes Back Occupation of Southern Argentina Site by 500 Years

Read Article Gustavo Martínez

Gustavo Martínez -

-

Swansea Council

Swansea Council -

-

Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities

Egyptian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities -

Barry Molloy

Barry Molloy

Loading...