Latest News

-

University of Aberdeen

University of Aberdeen -

Supreme Council of Antiquities

Supreme Council of Antiquities -

Skyview

Skyview -

Göran Burenhult

Göran Burenhult

-

National Museum of the Eastern Carpathians

National Museum of the Eastern Carpathians -

Hungarian Concession Infrastructure Development

Hungarian Concession Infrastructure Development

-

Sharon Zuhovitzky, courtesy of the Pontifical Biblical Institute

Sharon Zuhovitzky, courtesy of the Pontifical Biblical Institute -

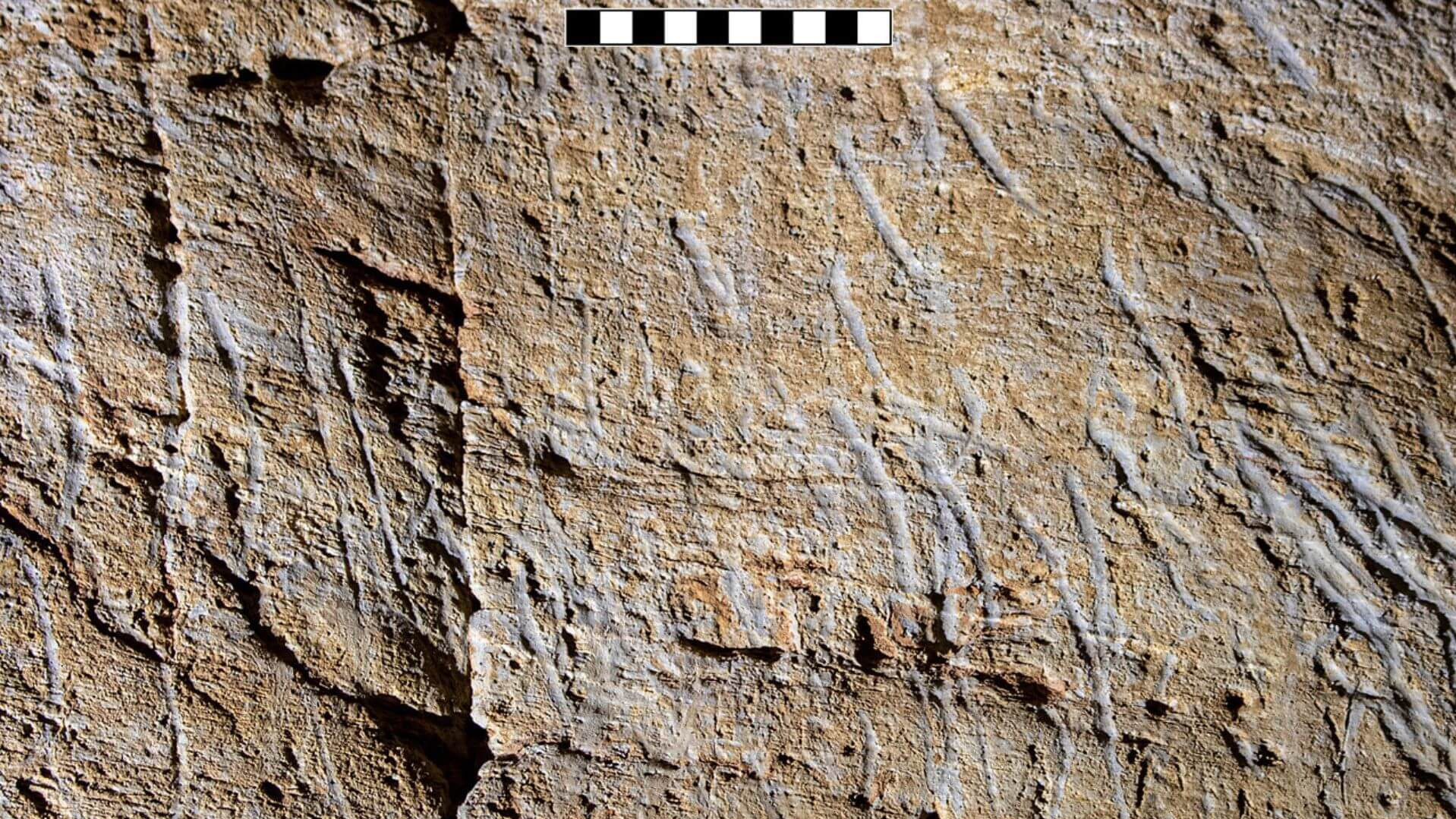

MaGMa Research Group

MaGMa Research Group

-

News February 18, 2026

Treated Fungus May Be the Secret to Greece’s Ancient Eleusinian Mysteries

Read Article ©Timetravelrome/Wikimedia Commons

©Timetravelrome/Wikimedia Commons -

Courtesy of the Mexican Embassy, Portugal

Courtesy of the Mexican Embassy, Portugal -

Emmanuelle Collado/INRAP

Emmanuelle Collado/INRAP -

Courtesy Hull City Council

Courtesy Hull City Council -

Model by Luk van Goor

Model by Luk van Goor -

News February 16, 2026

Remains of England's Earliest Known "Northerner" Belong to Mesolithic Girl

Read Article University of Lancashire

University of Lancashire -

News February 13, 2026

DNA Study Reveals Survival and Persistence of Low Countries Hunter-Gatherers

Read Article Provincial Depot for Archaeology Noord-Holland

Provincial Depot for Archaeology Noord-Holland -

Vitale Stefano Sparacello

Vitale Stefano Sparacello -

-

Jo Osborn

Jo Osborn -

© City of Cologne/Roman-Germanic Museum, Michael Wiehen

© City of Cologne/Roman-Germanic Museum, Michael Wiehen -

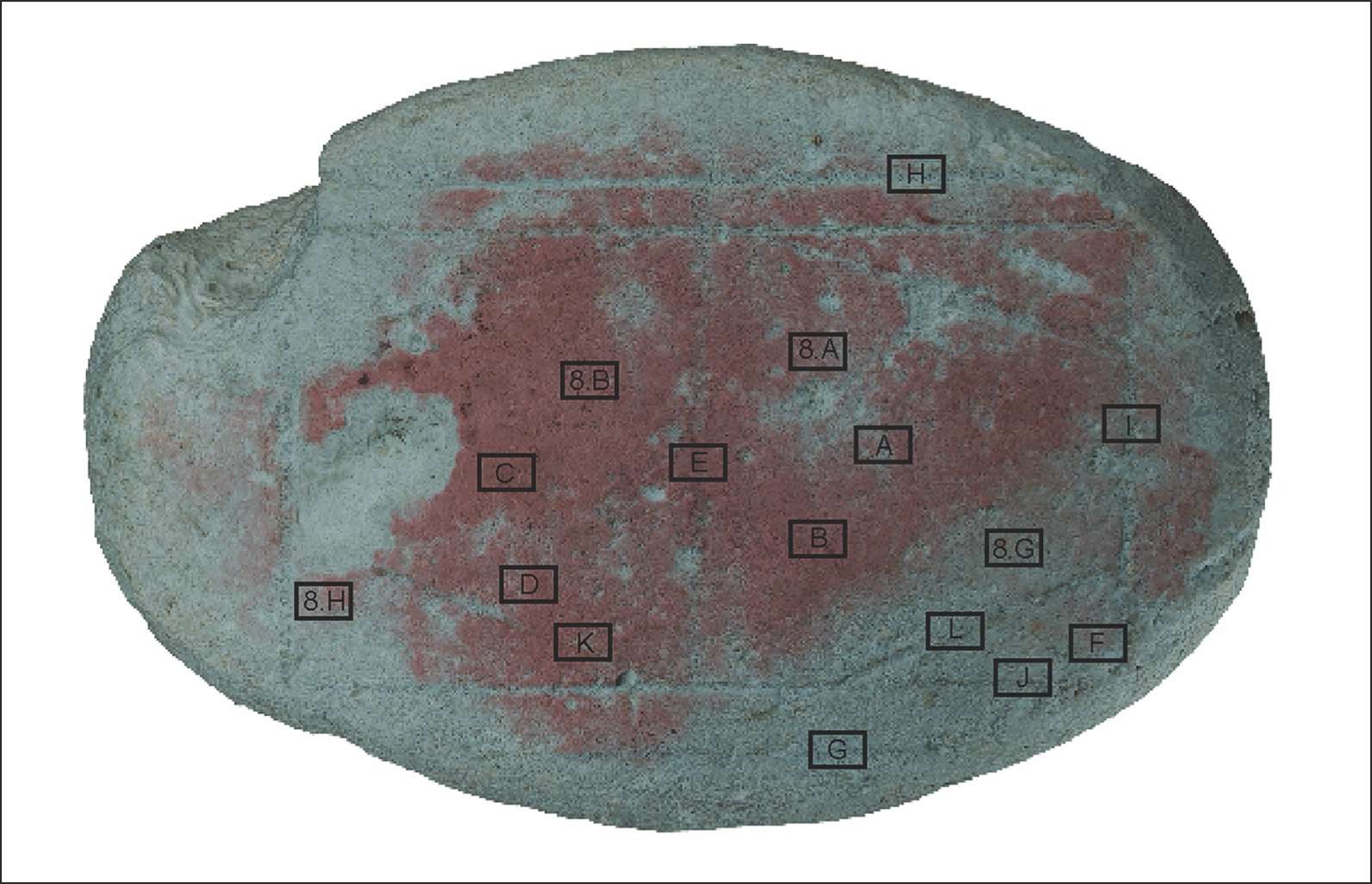

Walls, et al

Walls, et al

Loading...