Digs & Discoveries

Off the Grid

By ERIC A. POWELL

Friday, February 10, 2023

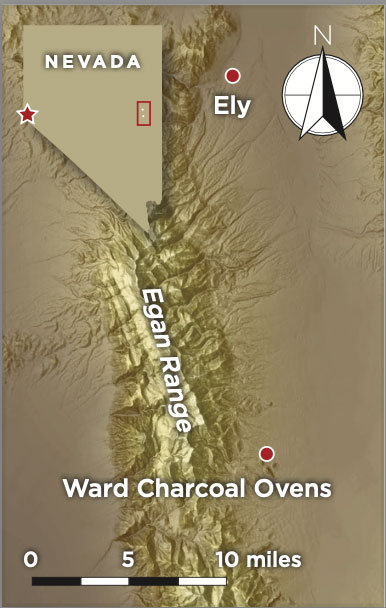

Tucked into a basin in eastern Nevada’s Egan Mountain Range is a curious row of six beehive-shaped stone constructions each measuring 30 feet tall and 27 feet wide at the base. These structures, which date to the 1870s, were once the backbone of the region’s booming silver industry. Used to produce the immense amount of charcoal needed to smelt silver ore extracted from nearby mines, such kilns consumed much of Nevada’s native pinyon pine and juniper stands. “Where there were mines, there were these charcoal ovens,” says Nevada State Parks Park Interpreter Dawn Andone. “Most have been lost to history, having either fallen apart or been vandalized. But at Ward Charcoal Ovens, you can see exactly how the charcoal industry functioned.” The ovens were crafted by Italian stonemasons in 1876 and replaced temporary charcoal pits that had been used to produce smelting fuel for the nearby Ward Mining District. For three years, workers in the employ of San Francisco’s Martin & White Company hauled wood to the ovens and oversaw a 10- to 12-day burning process that produced an estimated 1,750 bushels of charcoal per oven. Once the silver boom ended, the sturdy ovens provided temporary shelter for ranchers and travelers and, as local lore has it, were used as hideouts by stagecoach bandits.

Tucked into a basin in eastern Nevada’s Egan Mountain Range is a curious row of six beehive-shaped stone constructions each measuring 30 feet tall and 27 feet wide at the base. These structures, which date to the 1870s, were once the backbone of the region’s booming silver industry. Used to produce the immense amount of charcoal needed to smelt silver ore extracted from nearby mines, such kilns consumed much of Nevada’s native pinyon pine and juniper stands. “Where there were mines, there were these charcoal ovens,” says Nevada State Parks Park Interpreter Dawn Andone. “Most have been lost to history, having either fallen apart or been vandalized. But at Ward Charcoal Ovens, you can see exactly how the charcoal industry functioned.” The ovens were crafted by Italian stonemasons in 1876 and replaced temporary charcoal pits that had been used to produce smelting fuel for the nearby Ward Mining District. For three years, workers in the employ of San Francisco’s Martin & White Company hauled wood to the ovens and oversaw a 10- to 12-day burning process that produced an estimated 1,750 bushels of charcoal per oven. Once the silver boom ended, the sturdy ovens provided temporary shelter for ranchers and travelers and, as local lore has it, were used as hideouts by stagecoach bandits.

THE SITE

THE SITE

One of the least visited parks in the Nevada State Parks system, Ward Charcoal Ovens State Historic Park is located off U.S. 93 some 18 miles south of the town of Ely. The park is open year-round and has a small campground located across a seasonal creek from the ovens. Visitors are welcome to walk into the structures to get a look at the stonemasons’ immaculate work. A trail runs by the bluff where you can see quarries that furnished the stones used to make the ovens, the foundations of miners’ homes, and two cemeteries where workers were buried.

WHILE YOU’RE THERE

Ely serves as a gateway to the region’s many natural wonders, including Great Basin National Park, which is just an hour’s drive east. In downtown Ely, White Pine Public Museum has an exhibit dedicated to the history of silver mining in the area, as well as one focused on the 1982 discovery of the skeletons of two giant short-faced bears, extinct Ice Age creatures that stood 11 feet tall and were once North America’s largest carnivores. If you have time to stop for the night, Andone suggests staying in the town’s Hotel Nevada, one of the oldest inns in the state. She also recommends dropping by the Prospector Hotel, which features a busy gambling hall as well as Margarita’s Restaurant, where you can find some of the best Mexican food in Nevada.

Mounds in the Family

By ERIC A. POWELL

Friday, February 10, 2023

Some three decades ago, historian Charles Werth learned from a relative that there were Native American mounds on wooded property owned by his extended family near the town of Lebanon in southern Wisconsin’s Dodge County. But during his own visit to the purported site, Werth was unable to discern any features in the rolling landscape that appeared to have been created by people. Now retired, he used a drone in 2022 to photograph the woods in question and shared his images on social media forums dedicated to the area’s history.

Some three decades ago, historian Charles Werth learned from a relative that there were Native American mounds on wooded property owned by his extended family near the town of Lebanon in southern Wisconsin’s Dodge County. But during his own visit to the purported site, Werth was unable to discern any features in the rolling landscape that appeared to have been created by people. Now retired, he used a drone in 2022 to photograph the woods in question and shared his images on social media forums dedicated to the area’s history.

Archaeologist Kurt Sampson, curator of the Dodge County Historical Society Museum, was able to match Werth’s images with lidar imagery of the same coordinates and quickly identified two sites known as effigy mounds that were formed in the shape of animals. “The effigy mound shapes are so distinctive they are easily distinguished from natural features,” says Sampson. “They jumped right out.” Constructed to resemble a panther and a tadpole, the mounds were likely built between A.D. 600 and 1100 by ancestors of the Ho-Chunk people, whose traditional territory includes southern Wisconsin. Werth returned to the site to confirm the discovery. “When I went back, I realized that those nebulous mounds I had traversed years ago had discernible shape to them,” he says. Werth and Sampson are now working with the landowner and representatives of the Ho-Chunk Nation to preserve the mounds.

Winter Light

By DANIEL WEISS

Friday, February 10, 2023

A team of researchers from the University of Málaga and the University of Jaén believe they have discovered Egypt’s oldest tomb oriented toward the winter solstice sunrise. The tomb is located in the necropolis of Qubbet el-Hawa at Aswan in southern Egypt, on the western side of the Nile, opposite Elephantine Island. It is believed to date to the end of the 12th Dynasty, during the reign of the pharaoh Senwosret III (reigned ca. 1878–1840 B.C.) or Amenemhat III (reigned ca. 1859–1813 B.C.).

A team of researchers from the University of Málaga and the University of Jaén believe they have discovered Egypt’s oldest tomb oriented toward the winter solstice sunrise. The tomb is located in the necropolis of Qubbet el-Hawa at Aswan in southern Egypt, on the western side of the Nile, opposite Elephantine Island. It is believed to date to the end of the 12th Dynasty, during the reign of the pharaoh Senwosret III (reigned ca. 1878–1840 B.C.) or Amenemhat III (reigned ca. 1859–1813 B.C.).

The tomb was oriented so the sunrise on the winter solstice would shine through its doorway and down a corridor toward a chapel where a niche would have held a statue of the tomb’s occupant—most likely a provincial governor. Given that the days become longer starting on the winter solstice, the solstice symbolized the victory of sunlight over darkness. Ancient Egyptians believed that the sunlight hitting the statue transmitted energy that helped reactivate the vital force of the mummified body, which was buried directly below. To allow the greatest amount of sunlight to reach the chapel, the tomb’s doorway stood around 16 feet tall and was always open. “We found no trace of a door,” says Egyptologist Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano of the University of Jaén, who led the excavation of the tomb. “It’s clear that this entrance was made to receive the sun’s rays.”

The tomb was oriented so the sunrise on the winter solstice would shine through its doorway and down a corridor toward a chapel where a niche would have held a statue of the tomb’s occupant—most likely a provincial governor. Given that the days become longer starting on the winter solstice, the solstice symbolized the victory of sunlight over darkness. Ancient Egyptians believed that the sunlight hitting the statue transmitted energy that helped reactivate the vital force of the mummified body, which was buried directly below. To allow the greatest amount of sunlight to reach the chapel, the tomb’s doorway stood around 16 feet tall and was always open. “We found no trace of a door,” says Egyptologist Alejandro Jiménez-Serrano of the University of Jaén, who led the excavation of the tomb. “It’s clear that this entrance was made to receive the sun’s rays.”

According to Lola Joyanes, a professor of architecture at the University of Málaga, the tomb was actually angled 0.74 degrees south of a precise orientation toward the winter solstice sunrise. This appears to have been done intentionally, so that the brightest star in the sky—Sothis, now known as Sirius—would be visible from the tomb’s niche on the summer solstice. The summer solstice generally coincided with the beginning of the annual Nile flood, which was key to Egypt’s agricultural success. As such, both the summer and the winter solstice were associated with resurrection. “The architect or designer of the tomb was a genius,” says Jiménez-Serrano, “and showed great imagination in combining these two celestial events in a single monument.”

Closely Knit

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Friday, February 10, 2023

Four years after researchers discovered a triple burial in the English village of Cheddington, they have returned to study DNA samples taken from the remains. The burial, which dates to sometime between A.D. 251 and 433, contained two adult women—one between 25 and 29 years old, the other over 45 years old—and a fetus, possibly still in utero. “Simultaneous multiple burials from this time are fairly unusual,” says osteoarchaeologist Sharon Clough of Cotswold Archaeology. “And with there being two adult females and a preterm infant, it was intriguing to know if they were related in some way or if it was just convenient that they died at the same time.”

Four years after researchers discovered a triple burial in the English village of Cheddington, they have returned to study DNA samples taken from the remains. The burial, which dates to sometime between A.D. 251 and 433, contained two adult women—one between 25 and 29 years old, the other over 45 years old—and a fetus, possibly still in utero. “Simultaneous multiple burials from this time are fairly unusual,” says osteoarchaeologist Sharon Clough of Cotswold Archaeology. “And with there being two adult females and a preterm infant, it was intriguing to know if they were related in some way or if it was just convenient that they died at the same time.”

DNA analysis has revealed that the younger woman and the baby were mother and son. Clough was surprised to learn, however, that the older woman was unrelated to the younger one, but was related to the fetus, most likely as his paternal grandmother or aunt. “It’s not often we get a window into a moment over 1,600 years ago where a family loses three members of three different generations in a short time and chooses to bury them together,” says Clough. “It’s always a great honor and privilege to work with human remains. As a scientist you develop a clinical detachment working with the deceased. But you cannot help but feel the poignancy in this loss.”

Weapons of Choice

By ERIC A. POWELL

Friday, February 10, 2023

Archaeologists excavating at the Paleoindian site of Cooper’s Ferry in western Idaho have unearthed 14 stone projectiles with stems on their ends that date to some 16,000 years ago, making them the earliest such weapons to be discovered in North America. A team led by Oregon State University archaeologist Loren Davis discovered the points buried in two pits that appear to have been dug around the same time. The points were found along with stone waste flakes, bone fragments, and simpler stone tools. “The pits are the size of medium-sized garbage cans,” says Davis. “Maybe they were using them to clean up a dwelling we haven’t found yet.” He notes, however, that the points seem to be in good condition. “Perhaps they were being stored in equipment caches and were intended to be used after people came back to the site,” he says. Another possibility is that the points were retired as part of a ritual. The points’ shape resembles that of stemmed projectiles found in northern Japan that date to around 20,000 years ago. This raises the possibility that the people at Cooper’s Ferry may have been using a technology that originated somewhere around the Asian Pacific Rim.

Archaeologists excavating at the Paleoindian site of Cooper’s Ferry in western Idaho have unearthed 14 stone projectiles with stems on their ends that date to some 16,000 years ago, making them the earliest such weapons to be discovered in North America. A team led by Oregon State University archaeologist Loren Davis discovered the points buried in two pits that appear to have been dug around the same time. The points were found along with stone waste flakes, bone fragments, and simpler stone tools. “The pits are the size of medium-sized garbage cans,” says Davis. “Maybe they were using them to clean up a dwelling we haven’t found yet.” He notes, however, that the points seem to be in good condition. “Perhaps they were being stored in equipment caches and were intended to be used after people came back to the site,” he says. Another possibility is that the points were retired as part of a ritual. The points’ shape resembles that of stemmed projectiles found in northern Japan that date to around 20,000 years ago. This raises the possibility that the people at Cooper’s Ferry may have been using a technology that originated somewhere around the Asian Pacific Rim.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Digs & Discoveries

Peru’s Lost Temple

Bird Brains

Standing Swords

Earliest Ayahuasca Trip

Early Medieval Elegance

L is for Lice

Weapons of Choice

Winter Light

Closely Knit

Mounds in the Family

Off the Grid

Around the World

Snacking in the Colosseum, Japanese tomb statue, Attila the Hun’s motives, 300,000-year-old fur coats, and Egyptian crocodiles in the afterlife

Artifact

Tunes for all time

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement