Digs & Discoveries

L is for Lice

By ELIZABETH HEWITT

Friday, February 10, 2023

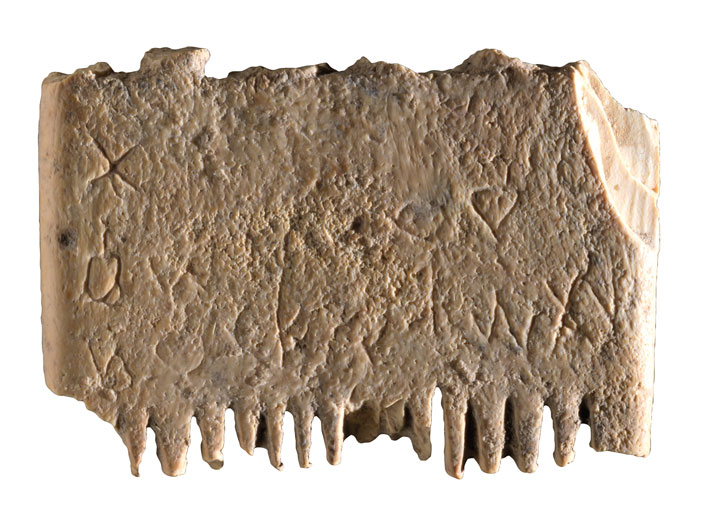

The earliest known full sentence to use an alphabetic script is inscribed on a small 3,700-year-old elephant-ivory comb that was unearthed in Israel. Although the comb was found in 2016 during excavations of the Canaanite city of Lachish, it was not until five years later that archaeologist Madeleine Mumcuoglu of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem noticed the 17 tiny characters, each measuring just 1/25 to 3/25 of an inch wide, faintly engraved on the comb’s surface. After translating the Canaanite script, epigraphist Daniel Vainstub of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev found that they spelled out a relatable appeal: “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.”

The earliest known full sentence to use an alphabetic script is inscribed on a small 3,700-year-old elephant-ivory comb that was unearthed in Israel. Although the comb was found in 2016 during excavations of the Canaanite city of Lachish, it was not until five years later that archaeologist Madeleine Mumcuoglu of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem noticed the 17 tiny characters, each measuring just 1/25 to 3/25 of an inch wide, faintly engraved on the comb’s surface. After translating the Canaanite script, epigraphist Daniel Vainstub of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev found that they spelled out a relatable appeal: “May this tusk root out the lice of the hair and the beard.”

The Canaanite script is a precursor to many modern alphabets. Some of its characters are recognizable in the Roman alphabet still in use today, according to Hebrew University of Jerusalem archaeologist Yosef Garfinkel, coleader of the Lachish excavations. These include qof, a monkey-inspired character consisting of two circles, one with a tail, that is an ancestor of the letter Q. The comb’s inscription is also evidence of the early alphabet’s use in everyday life, says Garfinkel. “It’s very personal.” And apparently at least partially successful, as lice remains were found on the teeth.

Early Medieval Elegance

By JASON URBANUS

Friday, February 10, 2023

A 1,300-year-old grave unearthed during construction of a housing complex in Northamptonshire has been hailed as the most significant early medieval female burial discovered in Britain. The collection of artifacts within the grave, which has been dubbed the Harpole Treasure, includes a necklace that is the most opulent of its type ever recovered. Composed of more than 30 pendants made from Roman coins, gold, glass, and semiprecious stones, the necklace has a cross-shaped gold and garnet centerpiece.

A 1,300-year-old grave unearthed during construction of a housing complex in Northamptonshire has been hailed as the most significant early medieval female burial discovered in Britain. The collection of artifacts within the grave, which has been dubbed the Harpole Treasure, includes a necklace that is the most opulent of its type ever recovered. Composed of more than 30 pendants made from Roman coins, gold, glass, and semiprecious stones, the necklace has a cross-shaped gold and garnet centerpiece.

Archaeologists lifted blocks of soil from the area immediately surrounding the burial and brought them back to a laboratory for further analysis. These have yet to be fully excavated, but X-rays have revealed some of the grave’s other precious artifacts, including an ornate silver cross bearing depictions of human faces. Although few skeletal remains survive, researchers from Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) believe that the objects likely belonged to a woman who died in the seventh century A.D. “The objects discovered in this burial and the sheer amount of Christian symbolism suggest she was a high-status individual,” says MOLA senior finds specialist Lyn Blackmore, “and may have been an early Christian leader.”

Archaeologists lifted blocks of soil from the area immediately surrounding the burial and brought them back to a laboratory for further analysis. These have yet to be fully excavated, but X-rays have revealed some of the grave’s other precious artifacts, including an ornate silver cross bearing depictions of human faces. Although few skeletal remains survive, researchers from Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) believe that the objects likely belonged to a woman who died in the seventh century A.D. “The objects discovered in this burial and the sheer amount of Christian symbolism suggest she was a high-status individual,” says MOLA senior finds specialist Lyn Blackmore, “and may have been an early Christian leader.”

Standing Swords

By JASON URBANUS

Friday, February 10, 2023

While excavating a Viking cemetery near the Swedish town of Köping, archaeologists discovered a pair of sword hilts protruding curiously from the earth. After further investigation, they determined that the handles belonged to Viking swords that had been thrust into the earth above two burials and had remained upright for 1,200 years. “Viking Age graves containing swords are very rare,” says Anton Seiler, an archaeologist working with Sweden’s National Historical Museums. “Graves where swords were set in a vertical position are even rarer.”

While excavating a Viking cemetery near the Swedish town of Köping, archaeologists discovered a pair of sword hilts protruding curiously from the earth. After further investigation, they determined that the handles belonged to Viking swords that had been thrust into the earth above two burials and had remained upright for 1,200 years. “Viking Age graves containing swords are very rare,” says Anton Seiler, an archaeologist working with Sweden’s National Historical Museums. “Graves where swords were set in a vertical position are even rarer.”

Because it would have taken a great amount of force to hammer the weapons through the soil and large stones that covered the burials, researchers do not believe the blades were in this position by chance. “It was clearly a conscious action,” Seiler says, though he is not certain why the swords were arranged in this unusual way. Perhaps, he says, it was a gesture meant to aid the deceased warriors’ journey to Valhalla. It also may have been a way of commemorating the dead. Family members visiting the graves would have been able to touch the sword handles, thereby maintaining a close connection with the departed.

Because it would have taken a great amount of force to hammer the weapons through the soil and large stones that covered the burials, researchers do not believe the blades were in this position by chance. “It was clearly a conscious action,” Seiler says, though he is not certain why the swords were arranged in this unusual way. Perhaps, he says, it was a gesture meant to aid the deceased warriors’ journey to Valhalla. It also may have been a way of commemorating the dead. Family members visiting the graves would have been able to touch the sword handles, thereby maintaining a close connection with the departed.

Earliest Ayahuasca Trip

By ZACH ZORICH

Friday, February 10, 2023

Analysis of hair from 22 mummies found in southern Peru has revealed the earliest known use of San Pedro cactus, a source of mescaline, and the psychoactive plants that make up the drug ayahuasca. The majority of the mummies were unearthed in Cahuachi, a religious center used by the Nazca people starting around 100 B.C. Coca plants and the Banisteriopsis caapi plant, better known as the liana vine, are among the substances detected in the mummies’ hair. The plants are not native to the region and were probably transported across the Andes Mountains. Researchers found that the drugs of choice changed over time. Ayahuasca and mescaline became less favored and coca consumption became more common after the Wari Empire conquered the Nazca around A.D. 750.

Analysis of hair from 22 mummies found in southern Peru has revealed the earliest known use of San Pedro cactus, a source of mescaline, and the psychoactive plants that make up the drug ayahuasca. The majority of the mummies were unearthed in Cahuachi, a religious center used by the Nazca people starting around 100 B.C. Coca plants and the Banisteriopsis caapi plant, better known as the liana vine, are among the substances detected in the mummies’ hair. The plants are not native to the region and were probably transported across the Andes Mountains. Researchers found that the drugs of choice changed over time. Ayahuasca and mescaline became less favored and coca consumption became more common after the Wari Empire conquered the Nazca around A.D. 750.

This shift may indicate changes in religious rituals surrounding human sacrifice. The find included four trophy heads, including one belonging to a child, who were sacrificial victims, but there is very little evidence of what role psychoactive substances played in the rituals. Bioarchaeologist Dagmara Socha of the University of Warsaw believes the antidepressant effects of the drugs may have been an important reason for their use. “In the case of the children that were sacrificed,” she says, “they were given Banisteriopsis caapi, probably because it was important for them to go happily to the gods.”

Bird Brains

By BRIDGET ALEX

Friday, February 10, 2023

For several centuries, between 5,550 and 4,750 years ago, Iberian farmers pursued a curious pastime: On palm-sized, trapezoidal slates, they engraved designs portraying creatures with round eyes and triangle-patterned coats. “It’s a local phenomenon pertaining to the southernmost part of the Iberian Peninsula,” says biologist Juan J. Negro of the Spanish National Research Council. Nearly 4,000 of these plaques have been recovered from megalithic tombs, pits, and other Copper Age (ca. 4500–2500 B.C.) sites in Spain and Portugal since the nineteenth century, and many archaeologists have assumed the engravings played a role in rituals, perhaps by representing goddesses. Recently, Negro and his colleagues have questioned this long-standing view.

For several centuries, between 5,550 and 4,750 years ago, Iberian farmers pursued a curious pastime: On palm-sized, trapezoidal slates, they engraved designs portraying creatures with round eyes and triangle-patterned coats. “It’s a local phenomenon pertaining to the southernmost part of the Iberian Peninsula,” says biologist Juan J. Negro of the Spanish National Research Council. Nearly 4,000 of these plaques have been recovered from megalithic tombs, pits, and other Copper Age (ca. 4500–2500 B.C.) sites in Spain and Portugal since the nineteenth century, and many archaeologists have assumed the engravings played a role in rituals, perhaps by representing goddesses. Recently, Negro and his colleagues have questioned this long-standing view.

Negro, who studies the remains of birds recovered from archaeological sites, noticed avian traits in the designs. Instead of goddesses, he thinks the designs depict owls, and that they were carved by children. Artificial intelligence software designed to recognize images also identified one of the plaques as depicting an owl. The youngsters, suggests Negro, may have chosen to sketch a familiar creature that provided a community service by hunting rodents that infested cereal stores.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Digs & Discoveries

Peru’s Lost Temple

Bird Brains

Standing Swords

Earliest Ayahuasca Trip

Early Medieval Elegance

L is for Lice

Weapons of Choice

Winter Light

Closely Knit

Mounds in the Family

Off the Grid

Around the World

Snacking in the Colosseum, Japanese tomb statue, Attila the Hun’s motives, 300,000-year-old fur coats, and Egyptian crocodiles in the afterlife

Artifact

Tunes for all time

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement