Lost Cities

Capital of the World’s First Empire

By DANIEL WEISS

Wednesday, April 10, 2024

The Akkadian Empire (ca. 2340–2198 B.C.) represented something entirely new in human history: a dynasty that conquered and ruled over a vast territory, incorporating people of different ethnicities who were forced to adopt its ways. At its height, the empire encompassed much of modern Iraq and parts of Syria, though its heartland is believed to have been the fertile plains of central Mesopotamia watered by the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Among other innovations, the empire’s founder, Sargon (reigned ca. 2340–2285 B.C.), instituted Ishtar, the Semitic goddess of war, as the patron deity of the dynasty, rather than of just a single city. A landmark of the Akkadian capital, Agade, was the Eulmash temple, dedicated to Ishtar. The Akkadians also pioneered new forms of art and writing, and their economic reach—including trade with the far-off Indus Valley—brought exotic goods and animals such as elephants, monkeys, and crocodiles to the capital. “Everywhere you looked, there was something new,” says Assyriologist Benjamin Foster of Yale University.

The Akkadian Empire (ca. 2340–2198 B.C.) represented something entirely new in human history: a dynasty that conquered and ruled over a vast territory, incorporating people of different ethnicities who were forced to adopt its ways. At its height, the empire encompassed much of modern Iraq and parts of Syria, though its heartland is believed to have been the fertile plains of central Mesopotamia watered by the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers. Among other innovations, the empire’s founder, Sargon (reigned ca. 2340–2285 B.C.), instituted Ishtar, the Semitic goddess of war, as the patron deity of the dynasty, rather than of just a single city. A landmark of the Akkadian capital, Agade, was the Eulmash temple, dedicated to Ishtar. The Akkadians also pioneered new forms of art and writing, and their economic reach—including trade with the far-off Indus Valley—brought exotic goods and animals such as elephants, monkeys, and crocodiles to the capital. “Everywhere you looked, there was something new,” says Assyriologist Benjamin Foster of Yale University.

Long after their empire fell, Akkadian rulers were seen as models by Mesopotamian dynasties such as the Assyrians and Babylonians. “Their relics were admired, their inscriptions were studied, and their historical memory was kept alive for two thousand years,” says Foster. Agade was largely abandoned, although its location was well known as late as the time of the Babylonian king Nabonidus (reigned 555–539 B.C.), who claimed to have excavated the Eulmash temple’s ruins. “I relaid the foundation, the altar, and dais, along with two ziggurats, and made firm its brickwork,” Nabonidus writes. “I built them up to ground level so that the foundation of Eulmash shall never again be forgotten.” Over time, though, the Eulmash temple, Agade, and the Akkadians themselves were, indeed, all forgotten. When Assyriologists rediscovered the cultures of ancient Mesopotamia in the mid-nineteenth century, they recognized Agade as the birthplace of an enduring style of political organization and took a keen interest in finding it. Yet, more than a century and a half later, the city remains lost.

Modern scholars believe the capital was located along the Tigris’ banks, roughly between the Iraqi cities of Baghdad and Samarra. However, the river has changed course over the millennia and may have washed away the remnants of Agade long ago. Nele Ziegler, an Assyriologist at the French National Center for Scientific Research, says that trying to determine Agade’s location involves a great deal of guesswork. “We don’t have many clues to where it is,” she says. “There’s no text that tells you, for instance, how much time it took to go from Sippar to Agade.” Ziegler is partial to a location near the confluence of the Adhaim and Tigris Rivers, around 50 miles north of Baghdad, in part based on an eighteenth-century B.C. text that describes a convoy traveling from the city of Eshnunna to the Kingdom of Mari. Along the way, the group stopped in Agade to drink beer, and a musician named Hushutum was kidnapped. Eshnunna is known to lie just east of Baghdad, and Mari is in far eastern Syria, so scholars can roughly estimate where Agade might have been. “We’d really like to find it,” says Ziegler. “There was a cultural revolution going on when the Akkadians came to power. It would be really interesting to see what they imagined as their ideal capital city.”

The Storm God’s City

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Wednesday, April 10, 2024

By the early thirteenth century B.C., the rulers of the Hittite Empire (ca. 1650–1200 B.C.) controlled most of central Anatolia and had expanded their territory by conquering new lands in western Anatolia and Syria. King Muwatalli II (reigned ca. 1295–1272 B.C.) moved royal operations from the original Hittite capital of Hattusha to Tarhuntasha, a city in southern Anatolia he named after the storm god Tarhunta. Cuneiform records from Muwatalli’s reign suggest that his motivation for the shift was religious reform. “Tarhunta had little prominence before Muwatalli,” says archaeologist Michele Massa of Bilkent University. “But the king decided to make this god the new head of the Hittite pantheon.” Scholars, however, believe there were likely other geopolitical factors that influenced the establishment of a new capital dedicated to Tarhunta. At the time, Muwatalli was enmeshed in a conflict with Egypt over Syria and Lebanon. “Hattusha was quite far north in Anatolia,” says archaeologist James Osborne of the University of Chicago, “and was a pretty inconvenient base from which to be campaigning when battles took place in the Levant.”

By the early thirteenth century B.C., the rulers of the Hittite Empire (ca. 1650–1200 B.C.) controlled most of central Anatolia and had expanded their territory by conquering new lands in western Anatolia and Syria. King Muwatalli II (reigned ca. 1295–1272 B.C.) moved royal operations from the original Hittite capital of Hattusha to Tarhuntasha, a city in southern Anatolia he named after the storm god Tarhunta. Cuneiform records from Muwatalli’s reign suggest that his motivation for the shift was religious reform. “Tarhunta had little prominence before Muwatalli,” says archaeologist Michele Massa of Bilkent University. “But the king decided to make this god the new head of the Hittite pantheon.” Scholars, however, believe there were likely other geopolitical factors that influenced the establishment of a new capital dedicated to Tarhunta. At the time, Muwatalli was enmeshed in a conflict with Egypt over Syria and Lebanon. “Hattusha was quite far north in Anatolia,” says archaeologist James Osborne of the University of Chicago, “and was a pretty inconvenient base from which to be campaigning when battles took place in the Levant.”

Tarhuntasha’s time at the center of the empire was brief—after Muwatalli’s death, the Hittite royal court moved back to Hattusha, but Tarhuntasha remained a province of the empire. Although Muwatalli’s son Kurunta was the legitimate royal heir, Muwatalli’s brother Hattushili III (reigned ca. 1267–1237 B.C.) ultimately seized the throne. He appeased his young nephew by naming him ruler of Tarhuntasha. Under Kurunta, Tarhuntasha became its own independent kingdom, but the precise extent of its territory—and the exact location of the capital city—are unknown. The most significant clues to Tarhuntasha’s location are found in treaties made with Kurunta by Hattushili and his son Tudhaliya IV (reigned ca. 1237–1209 B.C.). These treaties defined the borders separating Tarhuntasha and the Hittite Empire as somewhere between southern Turkey’s Konya Plain and the Mediterranean coast. “Because the treaties don’t mention where the city of Tarhuntasha is, pinpointing its location involves many different strands of evidence and a lot of detective work,” says Massa. New archaeological surveys and analysis of tablets and clay sealings unearthed at Hattusha may give Massa and Osborne’s team a chance to conclusively identify the site of the Hittite Empire’s elusive second capital.

Tarhuntasha’s time at the center of the empire was brief—after Muwatalli’s death, the Hittite royal court moved back to Hattusha, but Tarhuntasha remained a province of the empire. Although Muwatalli’s son Kurunta was the legitimate royal heir, Muwatalli’s brother Hattushili III (reigned ca. 1267–1237 B.C.) ultimately seized the throne. He appeased his young nephew by naming him ruler of Tarhuntasha. Under Kurunta, Tarhuntasha became its own independent kingdom, but the precise extent of its territory—and the exact location of the capital city—are unknown. The most significant clues to Tarhuntasha’s location are found in treaties made with Kurunta by Hattushili and his son Tudhaliya IV (reigned ca. 1237–1209 B.C.). These treaties defined the borders separating Tarhuntasha and the Hittite Empire as somewhere between southern Turkey’s Konya Plain and the Mediterranean coast. “Because the treaties don’t mention where the city of Tarhuntasha is, pinpointing its location involves many different strands of evidence and a lot of detective work,” says Massa. New archaeological surveys and analysis of tablets and clay sealings unearthed at Hattusha may give Massa and Osborne’s team a chance to conclusively identify the site of the Hittite Empire’s elusive second capital.

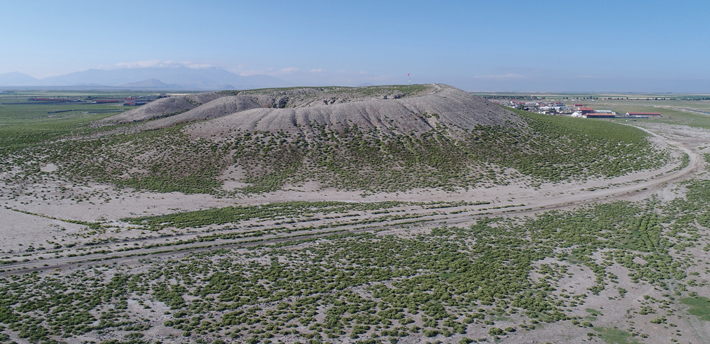

While studying satellite images of the Konya Plain, the team spotted the extensive mound site of Türkmen-Karahöyük. Because of its size and prominent location, they thought it could be an ancient political center—perhaps even Tarhuntasha itself. Massa and Osborne conducted a surface survey of the site and found ceramics that indicate the city there drastically expanded during the Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600–1200 B.C.), a period that includes Muwatalli’s transfer of the capital to Tarhuntasha. They also found a stone stela likely dating to the eighth century B.C. that records the achievements of a king named Hartapu, who styled himself as a “Great King,” a title also used by Kurunta, the only known ruler of the Kingdom of Tarhuntasha. More definitive evidence may soon be coming. The team has collected clay samples from Türkmen-Karahöyük and is comparing their geological signatures with those of clay tablets and sealings from Hattusha that are known to have originated in Tarhuntasha. Their work could finally put Tarhuntasha back on the map of the Hittite Empire.

Which Island Is it Anyway?

By JARRETT A. LOBELL

Wednesday, April 10, 2024

There are at least 17 places off the southern coast of Britain that modern scholars have suggested might be the island of Iktis, a major center of the Iron Age (ca. 750 B.C.–A.D. 43) tin trade. The confusion, however, didn’t begin in modern times, but rather with the multiple ancient authors who mention the island. The only one to call the island Iktis—without saying exactly where it could be found—is the first-century B.C. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus. Diodorus, who likely drew on other ancient Greek sources, reports that the Greek explorer Pytheas sailed to the British Isles in the fourth century B.C., landed in what is now Cornwall, saw the island, and wrote about it in his now-lost book On the Ocean. In his Library of History, Diodorus writes:

There are at least 17 places off the southern coast of Britain that modern scholars have suggested might be the island of Iktis, a major center of the Iron Age (ca. 750 B.C.–A.D. 43) tin trade. The confusion, however, didn’t begin in modern times, but rather with the multiple ancient authors who mention the island. The only one to call the island Iktis—without saying exactly where it could be found—is the first-century B.C. Greek historian Diodorus Siculus. Diodorus, who likely drew on other ancient Greek sources, reports that the Greek explorer Pytheas sailed to the British Isles in the fourth century B.C., landed in what is now Cornwall, saw the island, and wrote about it in his now-lost book On the Ocean. In his Library of History, Diodorus writes:

To an island which lies off Britain and is called Iktis, for at the time of ebb tide the space between this island and the mainland becomes dry and they can take the tin in large quantities to the island on their wagons…

In the first century A.D., the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder and the historian Suetonius used the name Vectis to refer to the Isle of Wight, which at some point became conflated with Diodorus’ Iktis, further muddying the waters. Pliny may also possibly reference Iktis in his Natural History when he refers to the island of Mictis—a name he got from the fourth-century B.C. Greek historian Timaeus—which, he writes, lies “six days sail from Britain where tin is found.”

Since at least the beginning of the nineteenth century, classicists and antiquarians have tried to pinpoint which island off the southern British coast is, in fact, the one to which these ancient writers refer—with little luck. And, despite repeated efforts, archaeologists, too, have resolved little except their commitment to their individual beliefs. Some say Iktis is Saint Michael’s Mount, a tidal island off Cornwall that once belonged to the same Benedictine monks who owned Mont-Saint-Michel off the French coast. Others believe it is a 60-foot-high limestone promontory jutting into Plymouth Sound now known as Mount Batten. Small-scale excavations were undertaken there beginning in the early nineteenth century, but little was recorded, and most of what remained there was destroyed during a WWII bombing raid. Nonetheless, finds including fourth-century B.C. fibulas, or pins, from northwest Iberia, brooches and bracelets made in the Iron Age La Tène style that was widespread across Europe, and coins of British Iron Age tribes suggest the site was heavily used during the Iron Age.

Although Pliny writes that the tin upon which peoples on the European continent and beyond depended was “found” on the island, that was certainly not the case. Rather, the raw material was traded in what twentieth-century University of Oxford archaeologist C. F. C. Hawkes called the island’s “tin mart.” Here Diodorus is perhaps a more reliable source when he writes, “On the island of Iktis the merchants purchase the tin of the natives…whence it is taken to Gaul overland to the Mediterranean.”

Korea’s City of Daggers

By HYUNG-EUN KIM

Wednesday, April 10, 2024

The origins of Gojoseon, the first Korean kingdom, are shrouded in myth. Although legend holds that it was founded by the king Dangun in 2333 B.C., Chinese records suggest that it emerged much later. The seventh-century B.C. Chinese history the Guanzi mentions that Gojoseon was an important kingdom, which scholars believe was on the Korean Peninsula or in a neighboring region of China. According to the first-century B.C. Chinese history the Shiji, by the second century B.C. the capital city of Gojoseon was known as Wanggeom-seong. But Chinese records are largely silent on its location. In the past, many historians believed that Wanggeom-seong was in the vicinity of Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea, based on what appeared to be a reference in the Shiji to what became Pyongyang.

The origins of Gojoseon, the first Korean kingdom, are shrouded in myth. Although legend holds that it was founded by the king Dangun in 2333 B.C., Chinese records suggest that it emerged much later. The seventh-century B.C. Chinese history the Guanzi mentions that Gojoseon was an important kingdom, which scholars believe was on the Korean Peninsula or in a neighboring region of China. According to the first-century B.C. Chinese history the Shiji, by the second century B.C. the capital city of Gojoseon was known as Wanggeom-seong. But Chinese records are largely silent on its location. In the past, many historians believed that Wanggeom-seong was in the vicinity of Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea, based on what appeared to be a reference in the Shiji to what became Pyongyang.

In the 1960s, a rare joint Chinese–North Korean archaeological excavation took place in China’s Liaoning Province at the site of a massive Gojoseon royal necropolis. The size of the complex suggested to some researchers that Wanggeom-seong must have been in the vicinity. About 140 people were buried in wooden coffins in 23 tombs at the necropolis. The tombs included rich grave goods such as a bronze dagger of a type that has emerged as key to defining the culture of Gojoseon.

Known as a mandolin-type dagger, after the shape of the stringed instrument, these artifacts are highly standardized, unlike pottery or stone monuments of the period, and have been used by archaeologists to define the limits of the Kingdom of Gojoseon. Researcher Jin-min Lee of the National Museum of Korea says that Korean scholars have studied Gojoseon daggers intensively, and the fact that so many have been found in Liaoning Province supports the idea that Wanggeom-seong might have been located there.

According to Chinese sources, Gojoseon fell in 108 B.C. Nonetheless, tombs with wooden coffins unique to Gojoseon continued to be built across what is today North Korea until at least the early first century A.D. Some historians believe this shows that the Gojoseon leadership maintained their power and control of the region and that Gojoseon culture carried on for perhaps 100 years after Chinese histories say the kingdom ended. Since Wanggeom-seong was the center of Gojoseon’s influence and power, identifying it could provide researchers with clues to how Gojoseon influence endured past the date it was traditionally thought to have ended.

Medieval Mountain Citadel

By BENJAMIN LEONARD

Wednesday, April 10, 2024

From at least the sixth to eighth century A.D., the diverse peoples of Central Asia’s Pamir Mountains were under the rule of various kingdoms, including the Shughnān Kingdom. Although there is a present-day region in Tajikistan and Afghanistan called Shughnān, scholars only have a slim understanding of this ancient kingdom’s history, even though it lay at the crossroads of major ancient trade and pilgrimage routes connecting China and India. According to the Tang Shu, a Chinese history of the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618–906), a town called Kǔhán was Shughnān’s capital. Seventh- and eighth-century A.D. Buddhist travelogues, as well as the Shahnameh, a Persian epic poem written around A.D. 1000, provide crucial, yet vague, details about the kingdom. “These texts state that Shughnān played an active and important role in the political, military, trading, and economic life of Central Asia,” says historian Muzaffar Zoolshoev of the Institute of Ismaili Studies. Little is known, however, about the origins of Shughnān, its borders, the lives of its people, or the location of Kǔhán. “Although the Tang history identifies Kǔhán as the capital, it doesn’t give any details about its location, size, or population,” Zoolshoev says. “No other historical sources mention it.” The names of three early Shughnān kings who are recorded in the Tang Shu suggest that the kingdom’s earliest rulers could have been descended from the nomadic Iranian-speaking Saka tribes, one of many groups that migrated to the region in the first millennium B.C. These people may have followed Zoroastrianism, a monotheistic faith that arose among Iranian-speaking people in the sixth century B.C. and involves worship in fire temples.

From at least the sixth to eighth century A.D., the diverse peoples of Central Asia’s Pamir Mountains were under the rule of various kingdoms, including the Shughnān Kingdom. Although there is a present-day region in Tajikistan and Afghanistan called Shughnān, scholars only have a slim understanding of this ancient kingdom’s history, even though it lay at the crossroads of major ancient trade and pilgrimage routes connecting China and India. According to the Tang Shu, a Chinese history of the Tang Dynasty (A.D. 618–906), a town called Kǔhán was Shughnān’s capital. Seventh- and eighth-century A.D. Buddhist travelogues, as well as the Shahnameh, a Persian epic poem written around A.D. 1000, provide crucial, yet vague, details about the kingdom. “These texts state that Shughnān played an active and important role in the political, military, trading, and economic life of Central Asia,” says historian Muzaffar Zoolshoev of the Institute of Ismaili Studies. Little is known, however, about the origins of Shughnān, its borders, the lives of its people, or the location of Kǔhán. “Although the Tang history identifies Kǔhán as the capital, it doesn’t give any details about its location, size, or population,” Zoolshoev says. “No other historical sources mention it.” The names of three early Shughnān kings who are recorded in the Tang Shu suggest that the kingdom’s earliest rulers could have been descended from the nomadic Iranian-speaking Saka tribes, one of many groups that migrated to the region in the first millennium B.C. These people may have followed Zoroastrianism, a monotheistic faith that arose among Iranian-speaking people in the sixth century B.C. and involves worship in fire temples.

Throughout the twentieth century, Soviet archaeologists documented traces of fortresses, settlements, and Saka burial grounds in Tajikistan that they tentatively dated to the era of the Shughnān Kingdom. They also identified numerous fire temples across the Pamir Mountains, including an unusual example that is circular with a square altar at the center, leading some archaeologists to speculate it was used by Saka who were followers of a fire or sun cult that was much more ancient than Zoroastrianism.

Based on historical texts and the available archaeological evidence, Zoolshoev has proposed more than 25 potential locations for Kǔhán within the modern-day region of Shughnān as well as elsewhere in Central Asia, including the ruined fortress of Karan in Tajikistan’s Darvaz district. Many of these sites have standing ruins of fortresses that have never been excavated or even formally recorded. “I hope this work will encourage historians and archaeologists to conduct further research that may reveal the site of the lost capital of Shughnān,” says Zoolshoev. Finding it, he says, would be a boon to scholars still struggling to understand the history of this mysterious kingdom.

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement