Lost Cities

London on the Black Sea

By ERIC A. POWELL

Wednesday, April 10, 2024

The fourteenth-century Icelandic Edwardsaga chronicles the life of Edward the Confessor, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England (reigned 1042–1066). It also describes how, in the years after the Norman Conquest in 1066—when William the Conqueror invaded England and was crowned king—350 ships carrying English warriors set out for Constantinople. There, the Byzantine emperor employed the Anglo-Saxons as members of the Varangian Guard, an elite unit of foreign soldiers that served as his personal army. Such was their loyalty, says the Edwardsaga, that the emperor deeded them land six days’ sailing north of Constantinople. There, presumably on the northern shores of the Black Sea, they are said to have occupied towns and cities with names such as London and York.

The fourteenth-century Icelandic Edwardsaga chronicles the life of Edward the Confessor, the last Anglo-Saxon king of England (reigned 1042–1066). It also describes how, in the years after the Norman Conquest in 1066—when William the Conqueror invaded England and was crowned king—350 ships carrying English warriors set out for Constantinople. There, the Byzantine emperor employed the Anglo-Saxons as members of the Varangian Guard, an elite unit of foreign soldiers that served as his personal army. Such was their loyalty, says the Edwardsaga, that the emperor deeded them land six days’ sailing north of Constantinople. There, presumably on the northern shores of the Black Sea, they are said to have occupied towns and cities with names such as London and York.

Medieval English towns on the Black Sea may sound like something out of an alternate history novel. But historian Jonathan Shepard of the University of Oxford says evidence has emerged to support the idea that in the late eleventh century, thousands of Anglo-Saxons did indeed seek out a new homeland in the Byzantine Empire. “There are so many references outside the saga to English soldiers in the Varangian Guard that we know many must have made their way to Byzantium,” he says. Seals belonging to two twelfth-century Byzantine interpreters serving in the Bureau of the Barbarians—an office founded in the fifth century A.D. to manage imperial relations with foreigners in residence in the empire—identify them as English translators. The seal of one, Constantine Kourtikios, calls him “the interpreter of the most faithful English.” On the banks of the Thames in London, archaeologists have documented a number of lead seals belonging to the Byzantine genikon, or chief financial ministry, most of which date to the end of the eleventh century. “These seals likely represent a flurry of Byzantine recruitment of disaffected Anglo-Saxons,” says Shepard. “William would probably have encouraged any effort to rid himself of these potential rebels.” As late as the fourteenth century, a Byzantine treatise on court ceremonies notes that the Varangians hailed the emperor “in their native tongue, that is, English.”

Medieval English towns on the Black Sea may sound like something out of an alternate history novel. But historian Jonathan Shepard of the University of Oxford says evidence has emerged to support the idea that in the late eleventh century, thousands of Anglo-Saxons did indeed seek out a new homeland in the Byzantine Empire. “There are so many references outside the saga to English soldiers in the Varangian Guard that we know many must have made their way to Byzantium,” he says. Seals belonging to two twelfth-century Byzantine interpreters serving in the Bureau of the Barbarians—an office founded in the fifth century A.D. to manage imperial relations with foreigners in residence in the empire—identify them as English translators. The seal of one, Constantine Kourtikios, calls him “the interpreter of the most faithful English.” On the banks of the Thames in London, archaeologists have documented a number of lead seals belonging to the Byzantine genikon, or chief financial ministry, most of which date to the end of the eleventh century. “These seals likely represent a flurry of Byzantine recruitment of disaffected Anglo-Saxons,” says Shepard. “William would probably have encouraged any effort to rid himself of these potential rebels.” As late as the fourteenth century, a Byzantine treatise on court ceremonies notes that the Varangians hailed the emperor “in their native tongue, that is, English.”

Evidence of Anglo-Saxon settlements on the northern fringes of the Byzantine Empire is more ephemeral. Fifteenth- and sixteenth-century Italian portolan maps, or nautical charts, show cities on the Black Sea coast with names such as Londina, Varangolimen, and Porto di Susacho that might plausibly have been the homes of soldiers who called themselves Saxons. And medieval Franciscan monks traveling through the area recorded people living there called “Saxi.” But no concerted effort has ever been made to correlate the cities on the maps with medieval sites, and archaeologists have yet to identify Anglo-Saxon artifacts in the region.

Perhaps, speculates Shepard, future DNA or isotope analysis of medieval people’s remains from Crimea will reveal ancestral ties to the British Isles. And artifacts or even buildings may still emerge that have an English cast. Until then, the cities of the first New England survive only on maps and in the words of the sagas.

Palaces of the Golden Horde

By ERIC A. POWELL

Wednesday, April 10, 2024

When Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales in the late fourteenth century, he set one of his stories in “Sarai, in the land of the Tartars.” At that time, Sarai was widely known as the capital of the mighty Golden Horde. An independent state within the Mongol Empire, the Golden Horde was initially led by the Islamic Jochid Dynasty, descendants of Genghis Khan’s oldest son, Jochi. From the 1240s until 1502, the Jochids and their successors held sway over the western Eurasian steppe, as well as much of Russia and Central Asia. Jochi’s son Batu is said to have founded Sarai as a seasonal residence near the banks of the Lower Volga River sometime in the 1250s.

When Chaucer wrote The Canterbury Tales in the late fourteenth century, he set one of his stories in “Sarai, in the land of the Tartars.” At that time, Sarai was widely known as the capital of the mighty Golden Horde. An independent state within the Mongol Empire, the Golden Horde was initially led by the Islamic Jochid Dynasty, descendants of Genghis Khan’s oldest son, Jochi. From the 1240s until 1502, the Jochids and their successors held sway over the western Eurasian steppe, as well as much of Russia and Central Asia. Jochi’s son Batu is said to have founded Sarai as a seasonal residence near the banks of the Lower Volga River sometime in the 1250s.

Lying at the nexus of vital long-distance trade routes, Sarai eventually grew from the site of the khan’s palace into a vast city of some 75,000, according to the fourteenth-century Arab traveler Ibn Battuta. “The descriptions of Sarai say you could ride for miles and not reach the city’s outskirts in one day,” says historian Marie Favereau of Paris Nanterre University. “Even allowing for exaggeration, we can imagine the site was quite spread out.” The khan and his retinue would visit the city annually, while artisans, diplomats, Islamic scholars, and Christian clerics remained in permanent residence. A second capital, New Sarai, is thought to have been founded upstream in the 1330s, when the Golden Horde was at its zenith. Jochid rule fractured in the late fourteenth century and later Mongol khans eventually gave way to Russian control by the mid-sixteenth century. Volga Valley residents then began to reuse mudbricks from Golden Horde–era cities, wiping them from the landscape.

After decades of debate, many Russian archaeologists believe Old Sarai once stood on a cliff at the edge of the Akhtuba River, a tributary of the Volga, at the site of Selitrennoe. They place New Sarai some 80 miles north, at the site of Tsarevskoe. But in recent years, some scholars have proposed that Tsarevskoe was a Jochid coin mint and that Selitrennoe was the site of both Old and New Sarai. Still others believe Old Sarai was located farther south on the Volga and was moved to Selitrennoe only after it was threatened by the rising waters of the Caspian Sea. “One problem is that there are almost 100 Mongol-era settlements along the Lower Volga,” says Favereau. “It can be difficult for archaeologists and historians to put names to specific sites.” Complicating the issue is that descriptions of Sarai were written by outsiders to the steppe, not the Mongols themselves, for whom Sarai was never an administrative center in the traditional sense. “In truth, the capital was wherever the khan was,” Favereau says. “He ruled from horseback.”

A few miles from Selitrennoe, an imposing set built for the 2012 Russian film The Horde to stand in for Sarai is now a state historical park. Its hulking buildings are monotone brown, but Favereau notes that Mongol-era tilework found in the region and surviving Mongol architecture from elsewhere in the empire suggest that Sarai, in all its possible incarnations, would have been full of color. “Blues would have been everywhere,” she says. “It was probably really beautiful.”

Kingdom of Kaabu’s Secret Capital

By ILANA HERZIG

Wednesday, April 10, 2024

Ensconced in the forested interior of modern-day Guinea-Bissau, the capital of the Kingdom of Kaabu, Kansala, was the region’s best-kept secret. Although far removed from major European trade routes, the city nevertheless dominated West Africa’s Senegambia region between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. “Kaabu traded with the Europeans and was involved in the slave trade,” says archaeologist Sirio Canós-Donnay of the Spanish National Research Council. “But no European ever set foot in the capital and they didn’t know where it was or even what it was called.”

Ensconced in the forested interior of modern-day Guinea-Bissau, the capital of the Kingdom of Kaabu, Kansala, was the region’s best-kept secret. Although far removed from major European trade routes, the city nevertheless dominated West Africa’s Senegambia region between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. “Kaabu traded with the Europeans and was involved in the slave trade,” says archaeologist Sirio Canós-Donnay of the Spanish National Research Council. “But no European ever set foot in the capital and they didn’t know where it was or even what it was called.”

With little to no previous archaeological evidence to draw on, a team of archaeologists and local sociologists and historians led by Canós-Donnay, Guinea-Bissau's National Research Institute (INEP), and Senegal's Ziguinchor University pieced together a timeline of Kaabu’s rise and fall. They pored over accounts of Islamic travelers and second-hand reports relayed by English, French, and Dutch traders, and compiled oral histories sung by local musicians and storytellers called griots. “The way history was reproduced and consumed was the domain of the griots,” Canós-Donnay says. Indeed, Kaabu is said to be where the kora, or West African harp, originated.

The team gleaned that while Kaabu consisted of a confederation of territories, its elected rulers—both women and men—hailed from three royal provinces that rotated into the seat of power at Kansala. Illustrations of Kaabu settlements depict zig-zagging mud fortifications, some with thatched roofs, multistory square towers equipped with defensive features including arrow slits and ramparts, and moats filled with thorns. “We have relied on local knowledge of these histories to connect archaeology with oral traditions to locate Kaabu sites,” says Canós-Donnay.

After excavating remnants of the kingdom in Senegal and armed with approximations of Kansala’s location, Canós-Donnay turned her focus to traces of a settlement in northern Guinea-Bissau where the team has unearthed evidence indicating it was a capital. “It’s interesting they chose a location so out of the way of any European trade routes for a kingdom deeply invested in trade,” she says. “They may have foreseen the danger posed by the Europeans and chosen a place they wouldn’t go for fear of disease and attack.” The team has only just begun to explore what remains of Kansala. They have identified two concentric enclosure walls, the ruler’s house, royal quarters, European cannons, and stone foundations of a gunpowder magazine said to have been blown up by Kaabu’s last king, who opted to destroy Kansala rather than surrender it to an enemy kingdom. “The capital’s dramatic end is still well remembered across the whole region,” says Canós-Donnay.

After excavating remnants of the kingdom in Senegal and armed with approximations of Kansala’s location, Canós-Donnay turned her focus to traces of a settlement in northern Guinea-Bissau where the team has unearthed evidence indicating it was a capital. “It’s interesting they chose a location so out of the way of any European trade routes for a kingdom deeply invested in trade,” she says. “They may have foreseen the danger posed by the Europeans and chosen a place they wouldn’t go for fear of disease and attack.” The team has only just begun to explore what remains of Kansala. They have identified two concentric enclosure walls, the ruler’s house, royal quarters, European cannons, and stone foundations of a gunpowder magazine said to have been blown up by Kaabu’s last king, who opted to destroy Kansala rather than surrender it to an enemy kingdom. “The capital’s dramatic end is still well remembered across the whole region,” says Canós-Donnay.

Local griots and elders, some from the village of Tabato, 60 miles southwest of the site, will now work alongside researchers and students from Guinea-Bissau, Senegal, and the Gambia to explore the findings from the capital. “It’s been rewarding to confirm oral traditions,” says Canós-Donnay. “The griots we’ve talked to are excited to be part of this conversation between archaeology, folklore, and traditional ways of reproducing history. Even the village elders have been behind the archaeology because we’re helping prove all these stories they’d heard from their grandparents.”

An Enduring Chiefdom

By ERIC A. POWELL

Wednesday, April 10, 2024

As described by the chroniclers of the sixteenth-century Spanish de Soto expedition, the woman known to history as the Lady of Cofitachequi made a dramatic entrance to an audience with Hernando de Soto and his officers somewhere in what is now South Carolina. On May 1, 1540, she was borne to the meeting on a litter decorated with brilliant white cloth. The chroniclers marveled that such a beautiful woman ruled one of the alliances of towns in the American Southeast now known as Mississippian chiefdoms. She evidently exercised canny diplomacy and headed off direct conflict by allowing the Spaniards to spend at least 10 days at Cofitachequi, a large town that lay along a river at the heart of her realm. The Spanish soldiers, some 600 strong, took over half of the settlement, building several temporary structures and robbing the chiefdom’s main temple of a cache of pearls before heading northwest. Another expedition led by the Spaniard Juan Pardo traveled to Cofitachequi between 1566 and 1568, and English colonist Henry Woodward recorded visiting in 1670. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, however, there are no more references to Cofitachequi in the historical record.

As described by the chroniclers of the sixteenth-century Spanish de Soto expedition, the woman known to history as the Lady of Cofitachequi made a dramatic entrance to an audience with Hernando de Soto and his officers somewhere in what is now South Carolina. On May 1, 1540, she was borne to the meeting on a litter decorated with brilliant white cloth. The chroniclers marveled that such a beautiful woman ruled one of the alliances of towns in the American Southeast now known as Mississippian chiefdoms. She evidently exercised canny diplomacy and headed off direct conflict by allowing the Spaniards to spend at least 10 days at Cofitachequi, a large town that lay along a river at the heart of her realm. The Spanish soldiers, some 600 strong, took over half of the settlement, building several temporary structures and robbing the chiefdom’s main temple of a cache of pearls before heading northwest. Another expedition led by the Spaniard Juan Pardo traveled to Cofitachequi between 1566 and 1568, and English colonist Henry Woodward recorded visiting in 1670. By the beginning of the eighteenth century, however, there are no more references to Cofitachequi in the historical record.

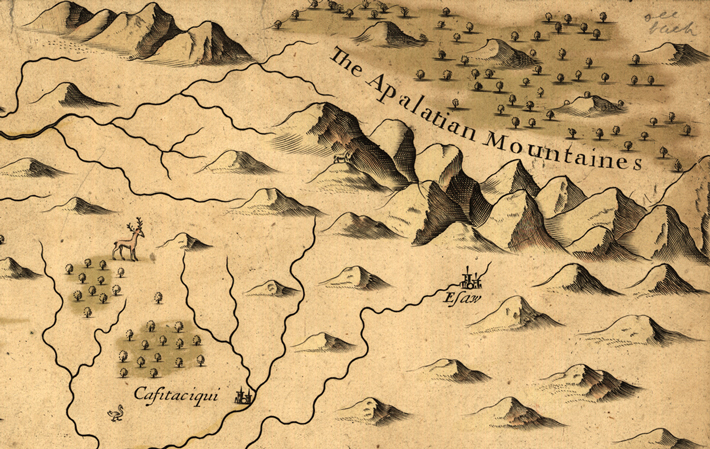

In the mid-twentieth century, scholars using the accounts of the de Soto expedition attempted to identify the location of Cofitachequi. Initially, some believed it was on the banks of the Savannah River, but now most researchers think it was somewhere on the Wateree River in north-central South Carolina. Several mound sites in the river valley might have been the town de Soto knew as Cofitachequi. “It’s not easy to figure out where Cofitachequi was,” says archaeologist Adam King of the University of South Carolina. He points out that finding Spanish artifacts at a site isn’t enough to tie it to de Soto’s descriptions. “European artifacts entered Indigenous trade and kin networks, so finding them at a site doesn’t mean the Spanish were there,” King says. However, identifying traces of Spanish-style structures at a site might help clinch its identification as Cofitachequi. “It was a medieval army traveling with pigs and horses,” says King. “They should have left a substantial footprint—if we can find it.”

The significance of locating Cofitachequi would go beyond simply identifying a stop on de Soto’s journey. “It’s often thought that Mississippian people were powerless and that after de Soto came through, their societies fell apart and they were erased from the landscape,” says King. “But Cofitachequi was a named place that endured for a long time. Finding it would help us tell that story.” Today, several Indigenous groups, including the Muscogee and Catawba Nations, claim a connection with the chiefdom. “Towns like Cofitachequi weren’t really towns so much as social groups,” says King. “They were people with histories, and those histories are connected to people who are still here.”

The significance of locating Cofitachequi would go beyond simply identifying a stop on de Soto’s journey. “It’s often thought that Mississippian people were powerless and that after de Soto came through, their societies fell apart and they were erased from the landscape,” says King. “But Cofitachequi was a named place that endured for a long time. Finding it would help us tell that story.” Today, several Indigenous groups, including the Muscogee and Catawba Nations, claim a connection with the chiefdom. “Towns like Cofitachequi weren’t really towns so much as social groups,” says King. “They were people with histories, and those histories are connected to people who are still here.”

When de Soto and his men left Cofitachequi, they forced the ruler they were so fascinated with to come with them as a hostage. For several days, the Lady of Cofitachequi traveled with her captors past the limits of her realm. Before reaching the lands of the next powerful chiefdom, though, she outwitted her guards and slipped away, presumably making her way back to Cofitachequi, where her descendants would continue to live for many generations.

Egypt’s First Capital?

By ILANA HERZIG

Thursday, April 11, 2024

The ancient Egyptian city of Tjenu, or Thinis, as it was later known to the Greeks, is as enigmatic as the many gods of Egypt’s pantheon. Although its existence is attested by ancient writers, the city’s location remains unknown. The early third-century B.C. Egyptian historian Manetho wrote of Thinis as the ancestral home of Egypt’s first rulers. These rulers, however, were interred at the sacred site of Abydos. For more than three millennia, the temples at Abydos—one of Egypt’s oldest cities and the cult center of Osiris, god of the underworld and afterlife—hosted festivals dedicated to Egyptian gods and kingship. “There’s literature characterizing the early kings, who were buried in the royal cemetery at Abydos, as Thinite, or part of the Thinite Dynasty,” says archaeologist Matthew Adams of New York University. “But there are times throughout the Pharaonic period (ca. 3100–332 B.C.) when Thinis is referring, in a general sense, to the broader region, including Abydos, rather than the ancient city of Thinis itself.” Abydos’ Umm el-Qa’ab cemetery held the tombs of 1st Dynasty rulers, including King Narmer and Queen Merneith, and the 2nd Dynasty kings Peribsen and Khasekhemwy. Most of these rulers probably hailed from Abydos, which was likely Egypt’s capital, not Thinis, as Manetho implies.

The ancient Egyptian city of Tjenu, or Thinis, as it was later known to the Greeks, is as enigmatic as the many gods of Egypt’s pantheon. Although its existence is attested by ancient writers, the city’s location remains unknown. The early third-century B.C. Egyptian historian Manetho wrote of Thinis as the ancestral home of Egypt’s first rulers. These rulers, however, were interred at the sacred site of Abydos. For more than three millennia, the temples at Abydos—one of Egypt’s oldest cities and the cult center of Osiris, god of the underworld and afterlife—hosted festivals dedicated to Egyptian gods and kingship. “There’s literature characterizing the early kings, who were buried in the royal cemetery at Abydos, as Thinite, or part of the Thinite Dynasty,” says archaeologist Matthew Adams of New York University. “But there are times throughout the Pharaonic period (ca. 3100–332 B.C.) when Thinis is referring, in a general sense, to the broader region, including Abydos, rather than the ancient city of Thinis itself.” Abydos’ Umm el-Qa’ab cemetery held the tombs of 1st Dynasty rulers, including King Narmer and Queen Merneith, and the 2nd Dynasty kings Peribsen and Khasekhemwy. Most of these rulers probably hailed from Abydos, which was likely Egypt’s capital, not Thinis, as Manetho implies.

Whether home to Egypt’s first pharaohs or not, Thinis became an influential political center of the 8th nome, or province, in Upper Egypt. “From the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649–2150 B.C.) on, Thinis was a provincial capital,” says Adams. “It had a mayor, overseers of priests, and extensive cemeteries that developed across the Nile.” Early Dynastic (ca. 3100–2649 B.C.) and Old Kingdom texts attest to the existence of a census, taxes, and irrigation systems. “Thinis seems to be this province’s primary administrative center for most of Pharaonic history,” says Adams.

Whether home to Egypt’s first pharaohs or not, Thinis became an influential political center of the 8th nome, or province, in Upper Egypt. “From the Old Kingdom (ca. 2649–2150 B.C.) on, Thinis was a provincial capital,” says Adams. “It had a mayor, overseers of priests, and extensive cemeteries that developed across the Nile.” Early Dynastic (ca. 3100–2649 B.C.) and Old Kingdom texts attest to the existence of a census, taxes, and irrigation systems. “Thinis seems to be this province’s primary administrative center for most of Pharaonic history,” says Adams.

Egyptologists know that Thinis’ sprawling cemeteries at the site of Naga ed-Deir on the Nile’s east bank lie across the river from the modern city of Girga—under which the remnants of Thinis may be buried. “The general location of Thinis can be identified because of these cemeteries,” Adams says. “But where, exactly, is the ancient archaeological site? It’s an open question.” A century ago, archaeological ruins were visible around the edges of Girga, but they were either obliterated or built over, and, explains Adams, can no longer be seen. “Nobody has gone looking or done archaeological reconnaissance or testing to find them,” he says. As with many ancient provincial towns in the Nile Valley, which have seen thousands of annual floods, Thinis’ remnants likely remain obscured under layers of alluvium that have been deposited over the millennia. For now, it seems that the once-great city, a potential key to understanding the rise of Egyptian civilization, has been lost to the desert from which it came. “It would be an extremely interesting site to investigate,” says Adams. “I would certainly urge somebody to give it a try.”

Advertisement

Advertisement

IN THIS ISSUE

Advertisement

Recent Issues

-

May/June 2024

May/June 2024

-

March/April 2024

March/April 2024

-

January/February 2024

January/February 2024

-

November/December 2023

November/December 2023

-

September/October 2023

September/October 2023

-

July/August 2023

July/August 2023

-

May/June 2023

May/June 2023

-

March/April 2023

March/April 2023

-

January/February 2023

January/February 2023

-

November/December 2022

November/December 2022

-

September/October 2022

September/October 2022

-

July/August 2022

July/August 2022

-

May/June 2022

May/June 2022

-

March/April 2022

March/April 2022

-

January/February 2022

January/February 2022

-

November/December 2021

November/December 2021

-

September/October 2021

September/October 2021

-

July/August 2021

July/August 2021

-

May/June 2021

May/June 2021

-

March/April 2021

March/April 2021

-

January/February 2021

January/February 2021

-

November/December 2020

November/December 2020

-

September/October 2020

September/October 2020

-

July/August 2020

July/August 2020

-

May/June 2020

May/June 2020

-

March/April 2020

March/April 2020

-

January/February 2020

January/February 2020

-

November/December 2019

November/December 2019

-

September/October 2019

September/October 2019

-

July/August 2019

July/August 2019

-

May/June 2019

May/June 2019

-

March/April 2019

March/April 2019

-

January/February 2019

January/February 2019

-

November/December 2018

November/December 2018

-

September/October 2018

September/October 2018

-

July/August 2018

July/August 2018

-

May/June 2018

May/June 2018

-

March/April 2018

March/April 2018

-

January/February 2018

January/February 2018

-

November/December 2017

November/December 2017

-

September/October 2017

September/October 2017

-

July/August 2017

July/August 2017

-

May/June 2017

May/June 2017

-

March/April 2017

March/April 2017

-

January/February 2017

January/February 2017

-

November/December 2016

November/December 2016

-

September/October 2016

September/October 2016

-

July/August 2016

July/August 2016

-

May/June 2016

May/June 2016

-

March/April 2016

March/April 2016

-

January/February 2016

January/February 2016

-

November/December 2015

November/December 2015

-

September/October 2015

September/October 2015

-

July/August 2015

July/August 2015

-

May/June 2015

May/June 2015

-

March/April 2015

March/April 2015

-

January/February 2015

January/February 2015

-

November/December 2014

November/December 2014

-

September/October 2014

September/October 2014

-

July/August 2014

July/August 2014

-

May/June 2014

May/June 2014

-

March/April 2014

March/April 2014

-

January/February 2014

January/February 2014

-

November/December 2013

November/December 2013

-

September/October 2013

September/October 2013

-

July/August 2013

July/August 2013

-

May/June 2013

May/June 2013

-

March/April 2013

March/April 2013

-

January/February 2013

January/February 2013

-

November/December 2012

November/December 2012

-

September/October 2012

September/October 2012

-

July/August 2012

July/August 2012

-

May/June 2012

May/June 2012

-

March/April 2012

March/April 2012

-

January/February 2012

January/February 2012

-

November/December 2011

November/December 2011

-

September/October 2011

September/October 2011

-

July/August 2011

July/August 2011

-

May/June 2011

May/June 2011

-

March/April 2011

March/April 2011

-

January/February 2011

January/February 2011

Advertisement